A Sheffield Hallam University Thesis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Research on Design Innovation for Reshaping Local Cultural Characteristics of the Tourist Souvenirs

E3S Web of Conferences 179, 02087 (2020) https://doi.org/10.1051/e3sconf/202017902087 EWRE 2020 Research on Design Innovation for Reshaping Local Cultural Characteristics of the Tourist Souvenirs Qiao Yang1 1Design Art and Media School, Nanjing University of Science and Technology, 21009, Nanjing, China Abstract. This article traces the essence of the tourist souvenir design, explaining the core of its value, the essence of local culture, and emphasizing the law of souvenir market value that maintains the uniqueness of local culture to attract purchases. By analysing the current situation of design homogeneity and lack of innovation in Chinese market, it proposes an innovative idea, “Back to Design Origins”. Then taking Nanjing souvenir design as an example, it introduces two innovative approaches, "Discovery and Application of New Cultural Elements" and " Cute Stylization of Traditional Symbols". In the end, it summarizes several feasible rules on element selection, symbolic method application, and carrier selection, mainly based on the thought of “Back to Design Origins”. 1 The essence of the tourist souvenir 2 The situation of Chinese souvenir design market Local traditional culture is an overall representation of Nowadays, although the tourist souvenir markets in the evolution and integration of a local civilization that various places have greatly increased in scale with the reflects the characteristics of the region and incorporates development of society, the quality and innovation of various ideological cultures and ideologies of local souvenirs have not improved simultaneously. Take history [1]. Tourist souvenirs can best reflect the most Beijing as an example. In 2009, 187 scenic spots in fundamental cultural characteristics of a resort or a city, Beijing received more than 150 million tourists, a year- showing particularity and irreplaceability. -

University of California Santa Cruz the Vietnamese Đàn

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA SANTA CRUZ THE VIETNAMESE ĐÀN BẦU: A CULTURAL HISTORY OF AN INSTRUMENT IN DIASPORA A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in MUSIC by LISA BEEBE June 2017 The dissertation of Lisa Beebe is approved: _________________________________________________ Professor Tanya Merchant, Chair _________________________________________________ Professor Dard Neuman _________________________________________________ Jason Gibbs, PhD _____________________________________________________ Tyrus Miller Vice Provost and Dean of Graduate Studies Table of Contents List of Figures .............................................................................................................................................. v Chapter One. Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 1 Geography: Vietnam ............................................................................................................................. 6 Historical and Political Context .................................................................................................... 10 Literature Review .............................................................................................................................. 17 Vietnamese Scholarship .............................................................................................................. 17 English Language Literature on Vietnamese Music -

Hsian.G Lectqres on Chinese.Poet

Hsian.g LectQres on Chinese.Poet: Centre for East Asian Research . McGill University Hsiang Lectures on Chinese Poetry Volume 7, 2015 Grace S. Fong Editor Chris Byrne Editorial Assistant Centre for East Asian Research McGill University Copyright © 2015 by Centre for East Asian Research, McGill University 688 Sherbrooke Street West McGill University Montreal, Quebec, Canada H3A 3R1 Calligraphy by: Han Zhenhu For additional copies please send request to: Hsiang Lectures on Chinese Poetry Centre for East Asian Research McGill University 688 Sherbrooke Street West Montreal, Quebec Canada H3A 3R1 A contribution of $5 towards postage and handling will be appreciated. This volume is printed on acid-free paper. Endowed by Professor Paul Stanislaus Hsiang (1915-2000) Contents Editor’s Note vii Nostalgia and Resistance: Gender and the Poetry of 1 Chen Yinke Wai-yee Li History as Leisure Reading for Ming-Qing Women Poets 27 Clara Wing-chung Ho Gold Mountain Dreams: Classical-Style Poetry from 65 San Francisco Chinatown Lap Lam Classical Poetry, Photography, and the Social Life of 107 Emotions in 1910s China Shengqing Wu Editor’s Note For many reasons, Volume 7 has taken much longer than anticipated to appear. One was the decision to wait in order to have four Hsiang Lectures in this volume rather than the customary three. The delay and small increase in the number of lectures bring new horizons in research on Chinese poetry to our readers. Indeed, in terms of the time frame covered, this volume focuses mostly, but not exclusively, on the twentieth century. Three of the four lectures are fascinating studies of the manifold significations of classical verse and their continued vitality in the discursive space of Chinese politics and culture in a century of modernization. -

The Preludes in Chinese Style

The Preludes in Chinese Style: Three Selected Piano Preludes from Ding Shan-de, Chen Ming-zhi and Zhang Shuai to Exemplify the Varieties of Chinese Piano Preludes D.M.A. DOCUMENT Presented in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Musical Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Jingbei Li, D.M.A. Graduate Program in Music The Ohio State University 2019 D.M.A. Document Committee: Professor Steven M. Glaser, Advisor Dr. Arved Ashby Dr. Edward Bak Copyrighted by Jingbei Li, D.M.A 2019 ABSTRACT The piano was first introduced to China in the early part of the twentieth century. Perhaps as a result of this short history, European-derived styles and techniques influenced Chinese composers in developing their own compositional styles for the piano by combining European compositional forms and techniques with Chinese materials and approaches. In this document, my focus is on Chinese piano preludes and their development. Having performed the complete Debussy Preludes Book II on my final doctoral recital, I became interested in comprehensively exploring the genre for it has been utilized by many Chinese composers. This document will take a close look in the way that three modern Chinese composers have adapted their own compositional styles to the genre. Composers Ding Shan-de, Chen Ming-zhi, and Zhang Shuai, while prominent in their homeland, are relatively unknown outside China. The Three Piano Preludes by Ding Shan-de, The Piano Preludes and Fugues by Chen Ming-zhi and The Three Preludes for Piano by Zhang Shuai are three popular works which exhibit Chinese musical idioms and demonstrate the variety of approaches to the genre of the piano prelude bridging the twentieth century. -

List of the 90 Masterpieces of the Oral and Intangible Heritage

Albania • Albanian Folk Iso-Polyphony (2005) Algeria • The Ahellil of Gourara (2005) Armenia • The Duduk and its Music (2005) Azerbaijan • Azerbaijani Mugham (2003) List of the 90 Masterpieces Bangladesh • Baul Songs (2005) of the Oral and Belgium • The Carnival of Binche (2003) Intangible Belgium, France Heritage of • Processional Giants and Dragons in Belgium and Humanity France (2005) proclaimed Belize, Guatemala, by UNESCO Honduras, Nicaragua • Language, Dance and Music of the Garifuna (2001) Benin, Nigeria and Tog o • The Oral Heritage of Gelede (2001) Bhutan • The Mask Dance of the Drums from Drametse (2005) Bolivia • The Carnival Oruro (2001) • The Andean Cosmovision of the Kallawaya (2003) Brazil • Oral and Graphic Expressions of the Wajapi (2003) • The Samba de Roda of Recôncavo of Bahia (2005) Bulgaria • The Bistritsa Babi – Archaic Polyphony, Dances and Rituals from the Shoplouk Region (2003) Cambodia • The Royal Ballet of Cambodia (2003) • Sbek Thom, Khmer Shadow Theatre (2005) Central African Republic • The Polyphonic Singing of the Aka Pygmies of Central Africa (2003) China • Kun Qu Opera (2001) • The Guqin and its Music (2003) • The Uyghur Muqam of Xinjiang (2005) Colombia • The Carnival of Barranquilla (2003) • The Cultural Space of Palenque de San Basilio (2005) Costa Rica • Oxherding and Oxcart Traditions in Costa Rica (2005) Côte d’Ivoire • The Gbofe of Afounkaha - the Music of the Transverse Trumps of the Tagbana Community (2001) Cuba • La Tumba Francesa (2003) Czech Republic • Slovácko Verbunk, Recruit Dances (2005) -

My Travels with the Guqin: a Personal Narrative in a Cross-Cultural Setting

My Travels with the GuQin: A personal narrative in a cross-cultural setting by Paul Henry Kemp B.Mus., The King’s University College, 2004 B.Ed., The University of Alberta, 2007 A Project Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF EDUCATION in the area of Music Education Department of Curriculum and Instruction Paul Henry Kemp, 2012 University of Victoria All rights reserved. This thesis may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without the permission of the author. ii Supervisory Committee My Travels With the GuQin: A personal narrative in a cross-cultural setting by Paul Henry Kemp B.Mus., The King’s University College, 2004 B.Ed., The University of Alberta, 2007 Supervisory Committee Dr. Mary A. Kennedy, (Department of Curriculum and Instruction) Supervisor Dr. Monica Prendergast, (Department of Curriculum and Instruction) Committee Member iii Abstract Supervisory Committee Dr. Mary A. Kennedy, (Department of Curriculum and Instruction) Supervisor Dr. Monica Prendergast, (Department of Curriculum and Instruction) Committee Member This project explored the significance of learning a global instrument in a cross- cultural setting. The question posed for this project was: “Can a music teacher change roles from teacher to student, move outside of the formalised classroom, and learn a music dissimilar to one’s own in a cross-cultural setting?” The cross-cultural setting was in Shanghai, China, and diverse cultural viewpoints, biases, and observations were recorded by means of journals, blogs, and informal music lessons. Every week, for one year, a one-hour informal lesson was taken on the GuQin. -

Download The

Pictures of Social Networks: Transforming Visual Representations of the Orchid Pavilion Gathering in the Tokugawa Period (1615-1868) by Kazuko Kameda-Madar B.A., The University of Hawai„i at Mānoa, 1997 M.A., The University of Hawai„i at Mānoa, 2002 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in The Faculty of Graduate Studies (Art History) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) May 2011 © Kazuko Kameda-Madar, 2011 Abstract This thesis examines the cultural networks that connected people holding common ideological values in the Tokugawa period by surveying a range of visual representations of the Orchid Pavilion Gathering. It explores the Tokugawa social phenomena that gave rise to the sudden boom in the Orchid Pavilion motif and how painters of different classes, belonging to different schools, such as Kano Sansetsu, Ike Taiga, Tsukioka Settei and Kubo Shunman, came to develop variations of this theme in order to establish cultural identity and to negotiate stronger positions in the relationships of social power. Probing the social environment of artists and their patrons, I demonstrate how distinct types of Orchid Pavilion imagery were invented and reinvented to advance different political agendas. The legendary gathering at the Orchid Pavilion in China took place in 353 CE, when Wang Xizhi invited forty-one scholars to participate in an annual Spring Purification Festival. At this event, Wang Xizhi improvised a short text that has come to be known as the Preface to the Orchid Pavilion Gathering. In Japan, while the practice of the ritual gathering and the text describing it were introduced in the Nara period, its pictorial representation in the format of a stone rubbing was not imported until the early seventeenth century. -

LCSH Section H

H (The sound) H.P. 15 (Bomber) Giha (African people) [P235.5] USE Handley Page V/1500 (Bomber) Ikiha (African people) BT Consonants H.P. 42 (Transport plane) Kiha (African people) Phonetics USE Handley Page H.P. 42 (Transport plane) Waha (African people) H-2 locus H.P. 80 (Jet bomber) BT Ethnology—Tanzania UF H-2 system USE Victor (Jet bomber) Hāʾ (The Arabic letter) BT Immunogenetics H.P. 115 (Supersonic plane) BT Arabic alphabet H 2 regions (Astrophysics) USE Handley Page 115 (Supersonic plane) HA 132 Site (Niederzier, Germany) USE H II regions (Astrophysics) H.P.11 (Bomber) USE Hambach 132 Site (Niederzier, Germany) H-2 system USE Handley Page Type O (Bomber) HA 500 Site (Niederzier, Germany) USE H-2 locus H.P.12 (Bomber) USE Hambach 500 Site (Niederzier, Germany) H-8 (Computer) USE Handley Page Type O (Bomber) HA 512 Site (Niederzier, Germany) USE Heathkit H-8 (Computer) H.P.50 (Bomber) USE Hambach 512 Site (Niederzier, Germany) H-19 (Military transport helicopter) USE Handley Page Heyford (Bomber) HA 516 Site (Niederzier, Germany) USE Chickasaw (Military transport helicopter) H.P. Sutton House (McCook, Neb.) USE Hambach 516 Site (Niederzier, Germany) H-34 Choctaw (Military transport helicopter) USE Sutton House (McCook, Neb.) Ha-erh-pin chih Tʻung-chiang kung lu (China) USE Choctaw (Military transport helicopter) H.R. 10 plans USE Ha Tʻung kung lu (China) H-43 (Military transport helicopter) (Not Subd Geog) USE Keogh plans Ha family (Not Subd Geog) UF Huskie (Military transport helicopter) H.R.D. motorcycle Here are entered works on families with the Kaman H-43 Huskie (Military transport USE Vincent H.R.D. -

Research on Bicycle Network Planning of Nanjing in China

Examensarbete i Hållbar Utveckling 22 Research on Bicycle Network Planning of Nanjing in China Ying Liang INSTITUTIONEN FÖR GEOVETENSKAPER RESEARCH ON BICYCLE NETWORK PLANNING OF NANJING IN CHINA YING LIANG UPPSALA UNIVERSITY SUPERRIVSED BY PER G BERG SWEDISH UNIVERSITY OF AGRICLTRUE SCIENCE (SLU) UPPSALA UNIVERSITY SPRING 2011 ii Abstract Although china has a huge cyclist population, the cycling condition in large cities is undesirable. The problem is mainly caused by the mixed-flow of cyclists and motorist on the road. Separation of cyclists and motorist is the key to solve the problem. Based on the research of the successful examples in Europe and a PEBOSCA inventory analysis of the cycling traffic in Nanjing, a set of suggestion is proposed on how to plan the bicycle network. A bicycle network separated from motor traffic and the planning on a cycling district division is introduced. The proposal also involves the suggestion on combination between cycling and public transport, and the experience route of historical culture and the natural beauty of the landscape. Keywords: Bicycle network planning, specific bicycle lane, urban transportation, PEBOSCA, Nanjing, China. Table of Content 1 Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Background: Transport problems of large cities in China ................................... 1 1.1.1 Sheer increase of motor vehicles .............................................................. 2 1.1.2 Imbalanced -

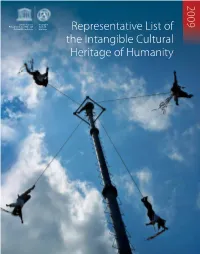

Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage Of

RL cover [temp]:Layout 1 1/6/10 17:35 Page 2 2009 United Nations Intangible Educational, Scientific and Cultural Cultural Organization Heritage Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity RL cover [temp]:Layout 1 1/6/10 17:35 Page 5 Rep List 2009 2.15:Layout 1 26/5/10 09:25 Page 1 2009 Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity Rep List 2009 2.15:Layout 1 26/5/10 09:25 Page 2 © UNESCO/Michel Ravassard Foreword by Irina Bokova, Director-General of UNESCO UNESCO is proud to launch this much-awaited series of publications devoted to three key components of the 2003 Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage: the List of Intangible Cultural Heritage in Need of Urgent Safeguarding, the Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity, and the Register of Good Safeguarding Practices. The publication of these first three books attests to the fact that the 2003 Convention has now reached the crucial operational phase. The successful implementation of this ground-breaking legal instrument remains one of UNESCO’s priority actions, and one to which I am firmly committed. In 2008, before my election as Director-General of UNESCO, I had the privilege of chairing one of the sessions of the Intergovernmental Committee for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage, in Sofia, Bulgaria. This enriching experience reinforced my personal convictions regarding the significance of intangible cultural heritage, its fragility, and the urgent need to safeguard it for future generations. Rep List 2009 2.15:Layout 1 26/5/10 09:25 Page 3 It is most encouraging to note that since the adoption of the Convention in 2003, the term ‘intangible cultural heritage’ has become more familiar thanks largely to the efforts of UNESCO and its partners worldwide. -

Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity As Heritage Fund

ElemeNts iNsCriBed iN 2012 oN the UrGeNt saFeguarding List, the represeNtatiVe List iNTANGiBLe CULtURAL HERITAGe aNd the reGister oF Best saFeguarding praCtiCes What is it? UNESCo’s ROLe iNTANGiBLe CULtURAL SECRETARIAT Intangible cultural heritage includes practices, representations, Since its adoption by the 32nd session of the General Conference in HERITAGe FUNd oF THE CoNVeNTION expressions, knowledge and know-how that communities recognize 2003, the Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural The Fund for the Safeguarding of the The List of elements of intangible cultural as part of their cultural heritage. Passed down from generation to Heritage has experienced an extremely rapid ratification, with over Intangible Cultural Heritage can contribute heritage is updated every year by the generation, it is constantly recreated by communities in response to 150 States Parties in the less than 10 years of its existence. In line with financially and technically to State Intangible Cultural Heritage Section. their environment, their interaction with nature and their history, the Convention’s primary objective – to safeguard intangible cultural safeguarding measures. If you would like If you would like to receive more information to participate, please send a contribution. about the 2003 Convention for the providing them with a sense of identity and continuity. heritage – the UNESCO Secretariat has devised a global capacity- Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural building strategy that helps states worldwide, first, to create -

A Study of Ping-Tan Narrative Vocal Tradition in Suzhou, China

Durham E-Theses Performing Local Identity in a Contemporary Urban Society: A Study of Ping-tan Narrative Vocal Tradition in Suzhou, China SHI, YINYUN How to cite: SHI, YINYUN (2016) Performing Local Identity in a Contemporary Urban Society: A Study of Ping-tan Narrative Vocal Tradition in Suzhou, China, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/11695/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 Abstract China has many rich traditions of storytelling and story singing, which are deeply rooted oral traditions in their particular geographical areas, carrying the linguistic and cultural flavours of their localities. In Suzhou, the central city of the Yangtze Delta’s Wu area, the storytelling genre pinghua and the story singing genre tanci have become emblematic of regional identity. Since the 1950s, the two genres have been referred to under the hybrid generic name ‘Suzhou ping-tan’ after the city, or simply ping-tan in abbreviation.