Ethnic Groups and Language Contact in Lycia (I): the ‘Maritime Interface’

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Georgy Kantor

Georgy Kantor Lycia et Pamphylia: A Social and Institutional History The project which I am proposing to undertake is a social and institutional history of the Roman province of Lycia and Pamphylia, from the process of establishment of Roman rule in the region in the late Republic and the Julio-Claudian period to the coming of Christianity and the separation of the constituent parts of the province in the early fourth century AD. The project aims at utilising different kinds of evidence – documentary, archaeological, numismatic, literary. Several factors combine to make such a study worthwhile. The isolated nature of the region, separated as it is by mountain ranges from the rest of Anatolia, and the fact that, with a very brief interruption, it has been a single administrative unit for more than two centuries, from the principate of Claudius to at least AD 312, allow us to treat it as a meaningful object of regional history. But below this unity there were striking distinctions between its different parts. In the course of my doctoral work on Roman and local law in the provinces of Asia Minor, I have found preliminary evidence to indicate that the ways in which Pamphylia and Lycia were governed by Rome were different in many crucial aspects. My project will thus provide an opportunity to study two models of Roman rule within one province, and it is at this level that we can best understand how Roman imperial structures worked and contribute to the ongoing discussion (re-opened by recent works of S. Dmitriev and C. -

Abd-Hadad, Priest-King, Abila, , , , Abydos, , Actium, Battle

INDEX Abd-Hadad, priest-king, Akkaron/Ekron, , Abila, , , , Akko, Ake, , , , Abydos, , see also Ptolemaic-Ake Actium, battle, , Alexander III the Great, Macedonian Adaios, ruler of Kypsela, king, –, , , Adakhalamani, Nubian king, and Syria, –, –, , , , Adulis, , –, Aegean Sea, , , , , , –, and Egypt, , , –, , –, – empire of, , , , , , –, legacy of, – –, –, , , death, burial, – Aemilius Paullus, L., cult of, , , Aeropos, Ptolemaic commander, Alexander IV, , , Alexander I Balas, Seleukid king, Afrin, river, , , –, – Agathokleia, mistress of Ptolemy IV, and eastern policy, , and Demetrios II, Agathokles of Syracuse, , –, and Seventh Syrian War, –, , , Agathokles, son of Lysimachos, – death, , , , Alexander II Zabeinas, , , Agathokles, adviser of Ptolemy IV, –, , , –, Alexander Iannai, Judaean king, Aigai, Macedon, , – Ainos, Thrace, , , , Alexander, son of Krateros, , Aitolian League, Aitolians, , , Alexander, satrap of Persis, , , –, , , – Alexandria-by-Egypt, , , , , , , , , , , , , Aitos, son of Apollonios, , , –, , , Akhaian League, , , , , , , –, , , , , , , , , , , , , , Akhaios, son of Seleukos I, , , –, –, , – , , , , , , –, , , , Akhaios, son of Andromachos, , and Sixth Syrian War, –, adviser of Antiochos III, , – Alexandreia Troas, , conquers Asia Minor, – Alexandros, son of Andromachos, king, –, , , –, , , –, , , Alketas, , , Amanus, mountains, , –, index Amathos, Cyprus, and battle of Andros, , , Amathos, transjordan, , Amestris, wife of Lysimachos, , death, Ammonias, Egypt, -

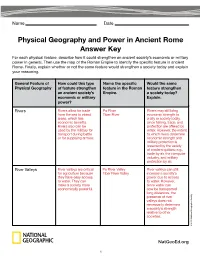

Physical Geography and Power in Ancient Rome Answer

Name Date Physical Geography and Power in Ancient Rome Answer Key For each physical feature, describe how it could strengthen an ancient society’s economic or military power in general. Then use the map of the Roman Empire to identify the specific feature in ancient Rome. Finally, explain whether or not the same feature would strengthen a society today and explain your reasoning. General Feature of How could this type Name the specific Would the same Physical Geography of feature strengthen feature in the Roman feature strengthen an ancient society’s Empire. a society today? economic or military Explain. power? Rivers Rivers allow for trade Po River Rivers may still bring from the sea to inland Tiber River economic strength to areas, which has a city or society today, economic benefits. since fishing, trade, and Rivers also can be protection are offered by used by the military for water. However, the extent transport during battle to which rivers determine or for supplying armies. economic strength and military protection is lessened by the variety of modern options: e.g., trade by air, the computer industry, and military protection by air. River Valleys River valleys are critical Po River Valley River valleys can still for agriculture because Tiber River Valley increase a society’s they have easy access power due to access to water. They can to water. However, make a society more since water can economically powerful. now be transported long distances, the presence of river valleys does not necessarily determine a society’s strength relative to other societies. © 2015 National Geographic Society NatGeoEd.org 1 Physical Geography and Power in Ancient Rome Answer Key, continued General Feature of How could this type Name the specific Would the same Physical Geography of feature strengthen feature in the Roman feature strengthen an ancient society’s Empire. -

CILICIA: the FIRST CHRISTIAN CHURCHES in ANATOLIA1 Mark Wilson

CILICIA: THE FIRST CHRISTIAN CHURCHES IN ANATOLIA1 Mark Wilson Summary This article explores the origin of the Christian church in Anatolia. While individual believers undoubtedly entered Anatolia during the 30s after the day of Pentecost (Acts 2:9–10), the book of Acts suggests that it was not until the following decade that the first church was organized. For it was at Antioch, the capital of the Roman province of Syria, that the first Christians appeared (Acts 11:20–26). Yet two obscure references in Acts point to the organization of churches in Cilicia at an earlier date. Among the addressees of the letter drafted by the Jerusalem council were the churches in Cilicia (Acts 15:23). Later Paul visited these same churches at the beginning of his second ministry journey (Acts 15:41). Paul’s relationship to these churches points to this apostle as their founder. Since his home was the Cilician city of Tarsus, to which he returned after his conversion (Gal. 1:21; Acts 9:30), Paul was apparently active in church planting during his so-called ‘silent years’. The core of these churches undoubtedly consisted of Diaspora Jews who, like Paul’s family, lived in the region. Jews from Cilicia were members of a Synagogue of the Freedmen in Jerusalem, to which Paul was associated during his time in Jerusalem (Acts 6:9). Antiochus IV (175–164 BC) hellenized and urbanized Cilicia during his reign; the Romans around 39 BC added Cilicia Pedias to the province of Syria. Four cities along with Tarsus, located along or near the Pilgrim Road that transects Anatolia, constitute the most likely sites for the Cilician churches. -

VU Research Portal

VU Research Portal The impact of empire on market prices in Babylon Pirngruber, R. 2012 document version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Link to publication in VU Research Portal citation for published version (APA) Pirngruber, R. (2012). The impact of empire on market prices in Babylon: in the Late Achaemenid and Seleucid periods, ca. 400 - 140 B.C. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal ? Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. E-mail address: [email protected] Download date: 25. Sep. 2021 THE IMPACT OF EMPIRE ON MARKET PRICES IN BABYLON in the Late Achaemenid and Seleucid periods, ca. 400 – 140 B.C. R. Pirngruber VRIJE UNIVERSITEIT THE IMPACT OF EMPIRE ON MARKET PRICES IN BABYLON in the Late Achaemenid and Seleucid periods, ca. 400 – 140 B.C. ACADEMISCH PROEFSCHRIFT ter verkrijging van de graad Doctor aan de Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, op gezag van de rector magnificus prof.dr. -

Physical Geography of Southeast Asia

Physical Geography of SE Asia ©2012, TESCCC World Geography Unit 12, Lesson 01 Archipelago • A group of islands. Cordilleras • Parallel mountain ranges and plateaus, that extend into the Indochina Peninsula. Living on the Mainland • Mainland countries include Myanmar, Thailand, Cambodia, Vietnam, and Laos • Laos is a landlocked country • The landscape is characterized by mountains, rivers, river deltas, and plains • The climate includes tropical and mild • The monsoon creates a dry and rainy season ©2012, TESCCC Identify the mainland countries on your map. LAOS VIETNAM MYANMAR THAILAND CAMBODIA Human Settlement on the Mainland • People rely on the rivers that begin in the mountains as a source of water for drinking, transportation, and irrigation • Many people live in small villages • The river deltas create dense population centers • River create rich deposits of sediment that settle along central plains ©2012, TESCCC Major Cities on the Mainland • Myanmar- Yangon (Rangoon), Mandalay • Thailand- Bangkok • Vietnam- Hanoi, Ho Chi Minh City (Saigon) • Cambodia- Phnom Penh ©2012, TESCCC Label the major cities on your map BANGKOK YANGON HO CHI MINH CITY PHNOM PEHN Chao Phraya River • Flows into the Gulf of Thailand, Bangkok is located along the river’s delta Irrawaddy River • Located in Myanmar, Rangoon located along the river Mekong River • Longest river in the region, forms part of the borders of Myanmar, Laos, and Thailand, empties into the South China Sea in Vietnam Label the important rivers and the bodies of water on your map. MEKONG IRRAWADDY CHAO PRAYA ©2012, TESCCC Living on the Islands • The island nations are fragmented • Nations are on islands are made up of island groups. -

295 Emanuela Borgia (Rome) CILICIA and the ROMAN EMPIRE

EMANUELA BORGIA, CILICIA AND THE ROMAN EMPIRE STUDIA EUROPAEA GNESNENSIA 16/2017 ISSN 2082-5951 DOI 10.14746/seg.2017.16.15 Emanuela Borgia (Rome) CILICIA AND THE ROMAN EMPIRE: REFLECTIONS ON PROVINCIA CILICIA AND ITS ROMANISATION Abstract This paper aims at the study of the Roman province of Cilicia, whose formation process was quite long (from the 1st century BC to 72 AD) and complicated by various events. Firstly, it will focus on a more precise determination of the geographic limits of the region, which are not clear and quite ambiguous in the ancient sources. Secondly, the author will thoroughly analyze the formation of the province itself and its progressive Romanization. Finally, political organization of Cilicia within the Roman empire in its different forms throughout time will be taken into account. Key words Cilicia, provincia Cilicia, Roman empire, Romanization, client kings 295 STUDIA EUROPAEA GNESNENSIA 16/2017 · ROME AND THE PROVINCES Quos timuit superat, quos superavit amat (Rut. Nam., De Reditu suo, I, 72) This paper attempts a systematic approach to the study of the Roman province of Cilicia, whose formation process was quite long and characterized by a complicated sequence of historical and political events. The main question is formulated drawing on – though in a different geographic context – the words of G. Alföldy1: can we consider Cilicia a „typical” province of the Roman empire and how can we determine the peculiarities of this province? Moreover, always recalling a point emphasized by G. Alföldy, we have to take into account that, in order to understand the characteristics of a province, it is fundamental to appreciate its level of Romanization and its importance within the empire from the economic, political, military and cultural points of view2. -

The Satrap of Western Anatolia and the Greeks

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2017 The aS trap Of Western Anatolia And The Greeks Eyal Meyer University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the Ancient History, Greek and Roman through Late Antiquity Commons Recommended Citation Meyer, Eyal, "The aS trap Of Western Anatolia And The Greeks" (2017). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 2473. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/2473 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/2473 For more information, please contact [email protected]. The aS trap Of Western Anatolia And The Greeks Abstract This dissertation explores the extent to which Persian policies in the western satrapies originated from the provincial capitals in the Anatolian periphery rather than from the royal centers in the Persian heartland in the fifth ec ntury BC. I begin by establishing that the Persian administrative apparatus was a product of a grand reform initiated by Darius I, which was aimed at producing a more uniform and centralized administrative infrastructure. In the following chapter I show that the provincial administration was embedded with chancellors, scribes, secretaries and military personnel of royal status and that the satrapies were periodically inspected by the Persian King or his loyal agents, which allowed to central authorities to monitory the provinces. In chapter three I delineate the extent of satrapal authority, responsibility and resources, and conclude that the satraps were supplied with considerable resources which enabled to fulfill the duties of their office. After the power dynamic between the Great Persian King and his provincial governors and the nature of the office of satrap has been analyzed, I begin a diachronic scrutiny of Greco-Persian interactions in the fifth century BC. -

Greek-Anatolian Language Contact and the Settlement of Pamphylia

CHRISTINA SKELTON Greek-Anatolian Language Contact and the Settlement of Pamphylia The Ancient Greek dialect of Pamphylia shows extensive influence from the nearby Anatolian languages. Evidence from the linguistics of Greek and Anatolian, sociolinguistics, and the histor- ical and archaeological record suggest that this influence is due to Anatolian speakers learning Greek as a second language as adults in such large numbers that aspects of their L2 Greek became fixed as a part of the main Pamphylian dialect. For this linguistic development to occur and persist, Pamphylia must initially have been settled by a small number of Greeks, and remained isolated from the broader Greek-speaking community while prevailing cultural atti- tudes favored a combined Greek-Anatolian culture. 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1 BACKGROUND The Greek-speaking world of the Archaic and Classical periods (ca. ninth through third centuries BC) was covered by a patchwork of different dialects of Ancient Greek, some of them quite different from the Attic and Ionic familiar to Classicists. Even among these varied dialects, the dialect of Pamphylia, located on the southern coast of Asia Minor, stands out as something unusual. For example, consider the following section from the famous Pamphylian inscription from Sillyon: συ Διϝι̣ α̣ ̣ και hιιαροισι Μανεˉ[ς .]υαν̣ hελε ΣελυW[ι]ιυ̣ ς̣ ̣ [..? hι†ια[ρ]α ϝιλ̣ σιι̣ ọς ̣ υπαρ και ανιιας̣ οσα περ(̣ ι)ι[στα]τυ ̣ Wοικ[. .] The author would like to thank Sally Thomason, Craig Melchert, Leonard Neidorf and the anonymous reviewer for their valuable input, as well as Greg Nagy and everyone at the Center for Hellenic Studies for allowing me to use their library and for their wonderful hospitality during the early stages of pre- paring this manuscript. -

The Carian Language HANDBOOK of ORIENTAL STUDIES SECTION ONE the NEAR and MIDDLE EAST

The Carian Language HANDBOOK OF ORIENTAL STUDIES SECTION ONE THE NEAR AND MIDDLE EAST Ancient Near East Editor-in-Chief W. H. van Soldt Editors G. Beckman • C. Leitz • B. A. Levine P. Michalowski • P. Miglus Middle East R. S. O’Fahey • C. H. M. Versteegh VOLUME EIGHTY-SIX The Carian Language by Ignacio J. Adiego with an appendix by Koray Konuk BRILL LEIDEN • BOSTON 2007 This book is printed on acid-free paper. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Adiego Lajara, Ignacio-Javier. The Carian language / by Ignacio J. Adiego ; with an appendix by Koray Konuk. p. cm. — (Handbook of Oriental studies. Section 1, The Near and Middle East ; v. 86). Includes bibliographical references. ISBN-13 : 978-90-04-15281-6 (hardback) ISBN-10 : 90-04-15281-4 (hardback) 1. Carian language. 2. Carian language—Writing. 3. Inscriptions, Carian—Egypt. 4. Inscriptions, Carian—Turkey—Caria. I. Title. II. P946.A35 2006 491’.998—dc22 2006051655 ISSN 0169-9423 ISBN-10 90 04 15281 4 ISBN-13 978 90 04 15281 6 © Copyright 2007 by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, The Netherlands. Koninklijke Brill NV incorporates the imprints Brill Hotei Publishers, IDC Publishers, Martinus Nijhoff Publishers, and VSP. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, translated, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission from the publisher. Authorization to photocopy items for internal or personal use is granted by Brill provided that the appropriate fees are paid directly to The Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Suite 910, Danvers, MA 01923, USA. -

Defining Ethnomusicology

10 1. THE HARMLESS DRUDGE : DEFINING ETHNOMUSICOLOGY DEFINITIONS. For years, people have been asking me the question: "You're an ethnomusicologist?" Shortly after 1950 it was likely to be accompanied by expressions of wonder and of the belief that I was somehow involved with "folk" music, with "primitive music," and particularly with "ancient music," and also that I must have a great deal of companionship with a tape recorder. By 1960 the questioner would likely bring up participation in an Indonesian gamelan, or perhaps an ability to "play" many of the world's odd instruments. In the 1970s, the conversation might well include the term "ethnic" music or even the etymologically outrageous "ethnomusic," and in the eighties and nineties, free association might lead to “diversity” and “world music.” I have always found it difficult to come to a precise, concise, and readily intelligible definition. Dictionaries differ considerably but espouse limited views. In the 120 years in which modern ethnomusicology can be said to have existed, since pioneer works such as those of Ellis (1885), Baker (1882), and Stumpf (1886), attitudes and orientations have changed greatly, and so has the name, from something very briefly called “Musikologie” (in the 1880s), to “comparative musicology” (through about 1950), then to “ethno- musicology” (1950–ca. 1956), quickly to “ethnomusicology” (removing the hyphen actually was an ideological move trying to signal disciplinary independence), with suggestions such as “cultural musicology” (Kerman 1985) and “socio-musicology” (Feld 1984) occasionally thrown in. The changes in name paralleled changes in intellectual orientation and emphasis. It is difficult to find a single, simple definition, to which most people in this field would subscribe, and thus ethnomusicologists have been perhaps excessively concerned with defining themselves. -

Archaeology and History of Lydia from the Early Lydian Period to Late Antiquity (8Th Century B.C.-6Th Century A.D.)

Dokuz Eylül University – DEU The Research Center for the Archaeology of Western Anatolia – EKVAM Colloquia Anatolica et Aegaea Congressus internationales Smyrnenses IX Archaeology and history of Lydia from the early Lydian period to late antiquity (8th century B.C.-6th century A.D.). An international symposium May 17-18, 2017 / Izmir, Turkey ABSTRACTS Edited by Ergün Laflı Gülseren Kan Şahin Last Update: 21/04/2017. Izmir, May 2017 Websites: https://independent.academia.edu/TheLydiaSymposium https://www.researchgate.net/profile/The_Lydia_Symposium 1 This symposium has been dedicated to Roberto Gusmani (1935-2009) and Peter Herrmann (1927-2002) due to their pioneering works on the archaeology and history of ancient Lydia. Fig. 1: Map of Lydia and neighbouring areas in western Asia Minor (S. Patacı, 2017). 2 Table of contents Ergün Laflı, An introduction to Lydian studies: Editorial remarks to the abstract booklet of the Lydia Symposium....................................................................................................................................................8-9. Nihal Akıllı, Protohistorical excavations at Hastane Höyük in Akhisar………………………………10. Sedat Akkurnaz, New examples of Archaic architectural terracottas from Lydia………………………..11. Gülseren Alkış Yazıcı, Some remarks on the ancient religions of Lydia……………………………….12. Elif Alten, Revolt of Achaeus against Antiochus III the Great and the siege of Sardis, based on classical textual, epigraphic and numismatic evidence………………………………………………………………....13. Gaetano Arena, Heleis: A chief doctor in Roman Lydia…….……………………………………....14. Ilias N. Arnaoutoglou, Κοινὸν, συμβίωσις: Associations in Hellenistic and Roman Lydia……….……..15. Eirini Artemi, The role of Ephesus in the late antiquity from the period of Diocletian to A.D. 449, the “Robber Synod”.……………………………………………………………………….………...16. Natalia S. Astashova, Anatolian pottery from Panticapaeum…………………………………….17-18. Ayşegül Aykurt, Minoan presence in western Anatolia……………………………………………...19.