Garry Johnson (June 2016)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Andy Higgins, BA

Andy Higgins, B.A. (Hons), M.A. (Hons) Music, Politics and Liquid Modernity How Rock-Stars became politicians and why Politicians became Rock-Stars Thesis submitted for the degree of Ph.D. in Politics and International Relations The Department of Politics, Philosophy and Religion University of Lancaster September 2010 Declaration I certify that this thesis is my own work and has not been submitted in substantially the same form for the award of a higher degree elsewhere 1 ProQuest Number: 11003507 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 11003507 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 Abstract As popular music eclipsed Hollywood as the most powerful mode of seduction of Western youth, rock-stars erupted through the counter-culture as potent political figures. Following its sensational arrival, the politics of popular musical culture has however moved from the shared experience of protest movements and picket lines and to an individualised and celebrified consumerist experience. As a consequence what emerged, as a controversial and subversive phenomenon, has been de-fanged and transformed into a mechanism of establishment support. -

Put on Your Boots and Harrington!': the Ordinariness of 1970S UK Punk

Citation for the published version: Weiner, N 2018, '‘Put on your boots and Harrington!’: The ordinariness of 1970s UK punk dress' Punk & Post-Punk, vol 7, no. 2, pp. 181-202. DOI: 10.1386/punk.7.2.181_1 Document Version: Accepted Version Link to the final published version available at the publisher: https://doi.org/10.1386/punk.7.2.181_1 ©Intellect 2018. All rights reserved. General rights Copyright© and Moral Rights for the publications made accessible on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. Please check the manuscript for details of any other licences that may have been applied and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. You may not engage in further distribution of the material for any profitmaking activities or any commercial gain. You may freely distribute both the url (http://uhra.herts.ac.uk/) and the content of this paper for research or private study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge. Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, any such items will be temporarily removed from the repository pending investigation. Enquiries Please contact University of Hertfordshire Research & Scholarly Communications for any enquiries at [email protected] 1 ‘Put on Your Boots and Harrington!’: The ordinariness of 1970s UK punk dress Nathaniel Weiner, University of the Arts London Abstract In 2013, the Metropolitan Museum hosted an exhibition of punk-inspired fashion entitled Punk: Chaos to Couture. -

Riotous Assembly: British Punk's Diaspora in the Summer of '81

Riotous assembly: British punk's diaspora in the summer of '81 Book or Report Section Accepted Version Worley, M. (2016) Riotous assembly: British punk's diaspora in the summer of '81. In: Andresen, K. and van der Steen, B. (eds.) A European Youth Revolt: European Perspectives on Youth Protest and Social Movements in the 1980s. Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 217-227. ISBN 9781137565693 Available at http://centaur.reading.ac.uk/52356/ It is advisable to refer to the publisher’s version if you intend to cite from the work. See Guidance on citing . Published version at: http://www.palgrave.com/gb/book/9781137565693 Publisher: Palgrave Macmillan All outputs in CentAUR are protected by Intellectual Property Rights law, including copyright law. Copyright and IPR is retained by the creators or other copyright holders. Terms and conditions for use of this material are defined in the End User Agreement . www.reading.ac.uk/centaur CentAUR Central Archive at the University of Reading Reading’s research outputs online Riotous Assembly: British punk’s diaspora in the summer of ‘81 Matthew Worley Britain’s newspaper headlines made for stark reading in July 1981.1 As a series of riots broke out across the country’s inner-cities, The Sun led with reports of ‘Race Fury’ and ‘Mob Rule’, opening up to provide daily updates of ‘Burning Britain’ as the month drew on.2 The Daily Mail, keen as always to pander a prejudice, described the disorder as a ‘Black War on Police’, bemoaning years of ‘sparing the rod’ and quoting those who blamed the riots on a ‘vociferous -

2 Punk – Eine Einleitung

DIPLOMARBEIT Titel der Diplomarbeit „Die Geschichte des Punk und seiner Szenen“ >Band 1 von 1< Verfasser Armin Wilfling angestrebter akademischer Grad Magister der Philosophie (Mag. phil.) Wien, 2009 Studienkennzahl lt. A 316 Studienblatt: Studienrichtung lt. Musikwissenschaft Studienblatt: Betreuerin / Betreuer: Dr. Emil Lubej Die Geschichte des Punk und seiner Szenen, Armin Wilfling Seite 2 1 KURZBESCHREIBUNGEN...................................................................................................................... 7 1.1 DEUTSCHSPRACHIGE ZUSAMMENFASSUNG ........................................................................................... 7 1.2 ENGLISH ABSTRACT .............................................................................................................................. 7 2 PUNK – EINE EINLEITUNG.................................................................................................................... 9 2.1 STILDEFINIERENDE MERKMALE DES PUNKS ......................................................................................... 9 2.2 LESEANLEITUNG ................................................................................................................................. 13 3 PUNK – EINE GESCHICHTE ................................................................................................................ 15 3.1 URSPRÜNGE UND VORLÄUFER ............................................................................................................ 17 3.1.1 Garage Rock................................................................................................................................. -

Call Sign Jan 08

January 2008 From the home of Dial-a-Cab International Inside this issue… Sid Gold leaves DaC after 42 years The DaC driver who enjoys 100 mile walks! DaC driver on Chris Tarrant quiz Keith Cain meets Westminster City Council re parking problems He doesn't just watch Strictly Come Dancing, this DaC driver How many different vehicles can is now British Champion! use a bus lane? You may be wrong! Why is this young lady Lib-Dem Mayoral candidate answers DaC driver’s questions sitting in the back of a DaC taxi with her own DaC driver’s wishes for 2008 terminal? DaC driver on fraud protection Call Sign January 2008 Page 2 NASH’S NUMBERS By Alan Nash (A95) Happy New Year to you all. Do you know your SM3 from your IG3? Outer London postal districts within the M25, a total of 135. If you want all 475 in the home counties visit www.nashsnumbers.co.uk BR1 Bromley EN5 Barnet KT12 Walton-on-T TW4 Hounslow BR2 pr Bromley HA0 Wembley KT13 Weybridge TW5 Hounslow BR2 8x Keston HA1 Harrow KT16 Chertsey TW6 Hounslow BR3 Beckenham HA2 Harrow KT17 Epsom TW7 Isleworth BR4 W. Wickham HA3 Harrow KT18 Epsom TW8 Brentford BR5 Orpington HA4 Ruislip KT19 Epsom TW9 Richmond BR6 Orpington HA5 Pinner KT20 Tadworth TW10 Richmond BR7 Chislehurst HA6 Northwood KT21 Ashtead TW11 Teddington BR8 Swanley HA7 Stanmore RG27 Hook TW12 Hampton CR0 Croydon HA8 Edgware RM1 Romford TW13 Feltham CR2 South Croydon HA9 Wembley RM2 Gidea Park TW14 Feltham CR3 Caterham IG1 Ilford RM3 Harold HillTW16 Sunbury-on-T CR4 Mitcham IG2 Ilford RM3 Harold Wood TW17 Shepperton CR5 Coulsdon IG3 -

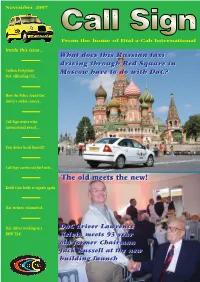

Call Sign Nov 07

November 2007 From the home of Dial-a-Cab International Inside this issue… WhatWhat doesdoes thisthis RussianRussian taxitaxi drivingdriving throughthrough RedRed SquareSquare inin Carbon Footprints: MoscowMoscow havehave toto dodo withwith DaC?DaC? DaC offloading CO2… How the Police found DaC driver’s stolen camera… Call Sign writer wins international award… Taxi driver heals himself! Call Sign carries out fuel tests… TheThe oldold meetsmeets thethe new!new! Keith Cain looks at signals again DaC website relaunched… DaC driver working in a DaCDaC drdriveriver LaLawrencewrence BMW TX4! KKelvinelvin meetsmeets 9393 yyearear oldold formerformer ChairmanChairman JJacackk RussellRussell atat thethe neneww buildingbuilding launclaunchh Call Sign November 2007 Page 2 NASH’S NUMBERS By Alan Nash (A95) The new Eurostar terminal opens at St. Pancras on 14 November 2007. This month I’ve tried to give you the arrival times to give you work and the travelling public a good service. On 9 October, the Eurostar website’s timetable was valid until July 07. I contacted Eurostar and they told me the website would be up to date on 10 October and they would also send me the St. Pancras timetable. I visited the website on 10 Oct and it was updated to show arrivals at Waterloo until 13/11/07! The timetable for St.Pancras has yet to arrive. So the following table was constructed by checking each train by arrival time for the first day (14 Nov) and the following week Mon to Sun. There were major changes in the early days of Waterloo Eurostar, which then settled into a fairly stable timetable. -

AS Sociology For

3.The mass media INTRODUCTION The focus of this opening section is an examination of different explanations of the relationship between ownership and control of the mass media and, in order to do this, we need to begin by thinking about how the mass media can be defined. person (the author of a book, for example), Defining mass communicates to many people (their readers) at the same time. This deceptively media simple definition does, of course, hide a number of complexities – such as, how large Preparing the does an audience have to be before it qualifies as ‘mass’? ground In addition to thinking about a basic We can start by breaking down the concept definition of the term, we can note how of a ‘mass media’ into its constituent parts. Dutton et al (Studying the Media, 1998) A medium, is a ‘channel of communication’ suggests that, traditionally (an important – a means through which people send and qualification I will develop in a moment), receive information. The printed word, for the mass media has been differentiated from example, is a medium; when we read a other types of communication (such as newspaper or magazine, something is interpersonal communication that occurs on communicated to us in some way. Similarly, a one-to-one basis) in terms of four essential electronic forms of communication – characteristics. television, telephones, film and such like – • Distance: Communication between those are media (the plural of medium). Mass who send and receive messages (media- means ‘many’ and what we are interested in speak for information) is impersonal, here is how and why different forms of lacks immediacy and is one way (from the media are used to transmit to – and be producer/creator of the information to the received by – large numbers of people (the consumer/audience). -

Abandoned Streets and Past Ruins of the Future in the Glossy Punk Magazine

This is a repository copy of Digging up the dead cities: abandoned streets and past ruins of the future in the glossy punk magazine. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/119650/ Version: Accepted Version Article: Trowell, I.M. orcid.org/0000-0001-6039-7765 (2017) Digging up the dead cities: abandoned streets and past ruins of the future in the glossy punk magazine. Punk and Post Punk, 6 (1). pp. 21-40. ISSN 2044-1983 https://doi.org/10.1386/punk.6.1.21_1 Reuse Unless indicated otherwise, fulltext items are protected by copyright with all rights reserved. The copyright exception in section 29 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 allows the making of a single copy solely for the purpose of non-commercial research or private study within the limits of fair dealing. The publisher or other rights-holder may allow further reproduction and re-use of this version - refer to the White Rose Research Online record for this item. Where records identify the publisher as the copyright holder, users can verify any specific terms of use on the publisher’s website. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ Digging up the Dead Cities: Abandoned Streets and Past Ruins of the Future in the Glossy Punk Magazine Abstract - This article excavates, examines and celebrates P N Dead! (a single issue printed in 1981), Punk! Lives (11 issues printed between 1982 and 1983) and Noise! (16 issues in 1982) as a small corpus of overlooked dedicated punk literature coincident with the UK82 incarnation of punk - that takes the form of a pop-style poster magazine. -

Authenticity, Politics and Post-Punk in Thatcherite Britain

‘Better Decide Which Side You’re On’: Authenticity, Politics and Post-Punk in Thatcherite Britain Doctor of Philosophy (Music) 2014 Joseph O’Connell Joseph O’Connell Acknowledgements Acknowledgements I could not have completed this work without the support and encouragement of my supervisor: Dr Sarah Hill. Alongside your valuable insights and academic expertise, you were also supportive and understanding of a range of personal milestones which took place during the project. I would also like to extend my thanks to other members of the School of Music faculty who offered valuable insight during my research: Dr Kenneth Gloag; Dr Amanda Villepastour; and Prof. David Wyn Jones. My completion of this project would have been impossible without the support of my parents: Denise Arkell and John O’Connell. Without your understanding and backing it would have taken another five years to finish (and nobody wanted that). I would also like to thank my daughter Cecilia for her input during the final twelve months of the project. I look forward to making up for the periods of time we were apart while you allowed me to complete this work. Finally, I would like to thank my wife: Anne-Marie. You were with me every step of the way and remained understanding, supportive and caring throughout. We have been through a lot together during the time it took to complete this thesis, and I am looking forward to many years of looking back and laughing about it all. i Joseph O’Connell Contents Table of Contents Introduction 4 I. Theorizing Politics and Popular Music 1. -

The Politics of Anarchy in Anarcho Punk,1977-1985

No Compromise with Their Society: The Politics of Anarchy in Anarcho Punk,1977-1985 Laura Dymock Faculty of Music, Department of Music Research, McGill University, Montréal September, 2007 A thesis submitted to McGill University in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Master of Arts, Musicology © Laura Dymock, 2007 Libraryand Bibliothèque et 1+1 Archives Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de l'édition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A ON4 Ottawa ON K1A ON4 Canada Canada Your file Votre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-38448-0 Our file Notre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-38448-0 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library permettant à la Bibliothèque et Archives and Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par télécommunication ou par l'Internet, prêter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des thèses partout dans loan, distribute and sell theses le monde, à des fins commerciales ou autres, worldwide, for commercial or non sur support microforme, papier, électronique commercial purposes, in microform, et/ou autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriété du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in et des droits moraux qui protège cette thèse. this thesis. Neither the thesis Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels de nor substantial extracts from it celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés ou autrement may be printed or otherwise reproduits sans son autorisation. -

Examensarbete Mall

5LI01E Examensarbete i litteraturvetenskap, master, 30 högskolepoäng Master’s thesis in comparative literature, 30 credits Oi! Oi! Oi? - en kulturkritisk studie av identitetsframställningen i Oi!-punken Författare: Björn Bradling Handledare: Piia Posti Examinator: Peter Forsgren Termin: HT15 Ämne: Litteraturvetenskap Nivå: Avancerad Kurskod: 5LI01E Abstract This master’s thesis suggests that Oi! - lyrically – gives voice to a youth community whose identity lies in everyday working class life. The identity in question is based upon class, gender, sexuality, nationality, and community awareness. As these are intertwined, the thesis shows a more complex genre than that of Matthew Worley’s “Oi! Oi! Oi!: Class, Locality, and British punk”. On the other hand, using the above categories - derived from the studies of Kathryn Woodward – allows this essay to detect a genre identity made from a distinct “the Same” and “the Other” – us and them, as described by Stuart Hall. The latter consists of members of the middle and upper classes along with all kinds of intellectuals. “The Same” is based upon a common belonging to the working class and its local communities, but also on nationhood. On the contrary, the male gender in general and the male sexuality in particular adds to the idea of Oi!´s “the Same”. In contrast to the idea of “the Same”, Stephen Greenblatt’s idea of dissonance works to explain cracks in the façade of Oi! as explained in the spatiotemporal discourse. Moreover, Oi!’s “the Same” is quite alike the subaltern of Antonio Gramsci. This concept suggests that the members of the proletariat are too unaware to be ideologically enlightened and therefore their culture expresses the way of working class life as it is, complete with eventual moral flaws. -

1BZ OP NPSF UIBO B

1BZOPNPSFUIBOb HITSVILLE UK: PUNK IN THE FARAWAY TOWNS Pg1 Roger Sabin During the punk years, I was lucky enough Catholic Girls. (In due course, the Small to live near one of the premier independent Wonder shop in London became a record label, Russell Bestley Pg2 Hitsville UK: Punk in faraway towns record shops, Small Wonder in Walthamstow, and signed up some of the top regional acts; London. Every time I visited, there would Bauhaus, from Northampton, the Cockney Pg4 From the First Wave to the New Wave be a new exhibition of art – by which, I Rejects from East London and The Cure, from mean the owner festooned the walls with the Crawley being the best-known. They declined, Pg5 Coloured Music latest seven-inch record sleeves. He’d also however, to sign my band – the rotters.) play the new sounds very loud, which meant Pg6 The Prole Art Threat his ‘gallery’ had a soundtrack. It was all There is a graphic design dimension to very mesmerising, and on a Saturday the shop the show (Bestley teaches the subject at Pg7 Key Categories in UK Punk would be packed with adolescents like me, university). But these sleeves were often not buying very much, but standing there not ‘designed’ in any conventional sense. Pg8 The Punk Community half-deaf and gawping like zombies. They were about mates deciding upon the most punkish/outrageous/amusing/dumb image, and Pg9 Proto Punk and Pub Rock Russ Bestley’s Hitsville UK: Punk in the then adding some typography – often filched Faraway Towns revives that sense of (small) from elsewhere or inexpertly lettrasetted Pg10 New Wave and Novelty Punk wonder, but isn’t just an exercise in on.