Hypnos/Somnus and Oneiros As Evidence for Incubation at Asklepieia: a Reassessment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hesiod Theogony.Pdf

Hesiod (8th or 7th c. BC, composed in Greek) The Homeric epics, the Iliad and the Odyssey, are probably slightly earlier than Hesiod’s two surviving poems, the Works and Days and the Theogony. Yet in many ways Hesiod is the more important author for the study of Greek mythology. While Homer treats cer- tain aspects of the saga of the Trojan War, he makes no attempt at treating myth more generally. He often includes short digressions and tantalizes us with hints of a broader tra- dition, but much of this remains obscure. Hesiod, by contrast, sought in his Theogony to give a connected account of the creation of the universe. For the study of myth he is im- portant precisely because his is the oldest surviving attempt to treat systematically the mythical tradition from the first gods down to the great heroes. Also unlike the legendary Homer, Hesiod is for us an historical figure and a real per- sonality. His Works and Days contains a great deal of autobiographical information, in- cluding his birthplace (Ascra in Boiotia), where his father had come from (Cyme in Asia Minor), and the name of his brother (Perses), with whom he had a dispute that was the inspiration for composing the Works and Days. His exact date cannot be determined with precision, but there is general agreement that he lived in the 8th century or perhaps the early 7th century BC. His life, therefore, was approximately contemporaneous with the beginning of alphabetic writing in the Greek world. Although we do not know whether Hesiod himself employed this new invention in composing his poems, we can be certain that it was soon used to record and pass them on. -

Disentangling Hypnos from His Poppies

EDITORIAL VIEWS Anesthesiology 2010; 113:271–2 Copyright © 2010, the American Society of Anesthesiologists, Inc. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins Disentangling Hypnos from His Poppies SUALLY a combination of opioid and hypnotic drugs theory, the CI can be interpreted as an indicator of the in- Uare used to achieve a state of balanced general anesthe- tensity of sub-cortical input. They found that increasing con- sia in the surgical patient. As evidenced by the great variation centrations of remifentanil caused a profound decrease in Downloaded from http://pubs.asahq.org/anesthesiology/article-pdf/113/2/271/251266/0000542-201008000-00006.pdf by guest on 02 October 2021 in practice, a fundamental but unanswered question is “How this parameter that was most marked in the presence of high much opioid should be given intraoperatively?” In Greek propofol concentrations. The CI index correlates well with mythology, Hypnos was the god of sleep. He lived on the the absolute amplitude of the electroencephalograph. The island of Lemnos in a dark cave surrounded by poppies. One propofol-induced increase in electroencephalographic am- of his sons was Morpheus, who gave form to the dreams of plitude is, therefore, suppressed by the concomitant adminis- kings and heroes. The article by Liley et al.1 in this issue of tration of remifentanil. In this respect, the CI index is markedly ANESTHESIOLOGY proposes an electroencephalographic index different from almost all the other electroencephalographic of opioid effect. Perhaps, this study has given us a tool to monitors in common use (such as the bispectral index and var- dissect out the influence of the poppies on Hypnos? ious entropies), the algorithms of which are designed to ignore Previous work on the electroencephalographic effects of the information contained in absolute amplitude of the electro- opioids is somewhat contradictory. -

Did Ancient People Wander Through a Mystical World Each Night?

Special Special Feature Human Knowledge: Sleep Feature Sleep = a state of apparent death Human Knowledge Did Ancient People Wander through a Mystical World The Sleeping Cat carved into Nikko Toshogu Shrine Sleep Each Night? is a symbol of peace The Sleeping Cat carved into Nikko Toshogu Shrine, in Tochigi Prefecture, is said to have been carved by Hidari Jingoro, in the hope of In modern times, people have strayed protecting Tokugawa Ieyasu. Another explana- Why do humans sleep? The answer tion rests on the premise that sleep represented from the natural human instinct of sleep. to this question is clear: sleep is peace, in that the reign of the Edo Shogunate instinctive and is indispensable for was said to be “so peaceful that even cats We need advancements in the scientific approach to sleep. the restoration of the body’s func- could sleep.” tions. Sleep is essential for human life. However, in ancient times, sleep was considered closer to death than between this world and the heavens. remain unknown. to life, and was general thought of The things that the spirit experienced For example, it is said that beds as a state of apparent death. This there became dreams, and if the spirit were invented in ancient Egypt; theme is also apparent in Hypnos, did not return, this was interpreted to however, it is not clear how they later the Greek god of sleep, who is broth- mean death. spread. In Japan, there is evidence ers with Oneiros, the god of dreams, Although sleep was the state that bed-like furniture made from tree as well as Thanatos and Moros, gods of rest shared by everyone, logs was once used. -

Mercury (Mythology) 1 Mercury (Mythology)

Mercury (mythology) 1 Mercury (mythology) Silver statuette of Mercury, a Berthouville treasure. Ancient Roman religion Practices and beliefs Imperial cult · festivals · ludi mystery religions · funerals temples · auspice · sacrifice votum · libation · lectisternium Priesthoods College of Pontiffs · Augur Vestal Virgins · Flamen · Fetial Epulones · Arval Brethren Quindecimviri sacris faciundis Dii Consentes Jupiter · Juno · Neptune · Minerva Mars · Venus · Apollo · Diana Vulcan · Vesta · Mercury · Ceres Mercury (mythology) 2 Other deities Janus · Quirinus · Saturn · Hercules · Faunus · Priapus Liber · Bona Dea · Ops Chthonic deities: Proserpina · Dis Pater · Orcus · Di Manes Domestic and local deities: Lares · Di Penates · Genius Hellenistic deities: Sol Invictus · Magna Mater · Isis · Mithras Deified emperors: Divus Julius · Divus Augustus See also List of Roman deities Related topics Roman mythology Glossary of ancient Roman religion Religion in ancient Greece Etruscan religion Gallo-Roman religion Decline of Hellenistic polytheism Mercury ( /ˈmɜrkjʉri/; Latin: Mercurius listen) was a messenger,[1] and a god of trade, the son of Maia Maiestas and Jupiter in Roman mythology. His name is related to the Latin word merx ("merchandise"; compare merchant, commerce, etc.), mercari (to trade), and merces (wages).[2] In his earliest forms, he appears to have been related to the Etruscan deity Turms, but most of his characteristics and mythology were borrowed from the analogous Greek deity, Hermes. Latin writers rewrote Hermes' myths and substituted his name with that of Mercury. However, there are at least two myths that involve Mercury that are Roman in origin. In Virgil's Aeneid, Mercury reminds Aeneas of his mission to found the city of Rome. In Ovid's Fasti, Mercury is assigned to escort the nymph Larunda to the underworld. -

PERSEPHONE a Musical Allegory for the Stage by David Hoffman

PERSEPHONE A Musical Allegory for the Stage By David Hoffman In Concert Performance www.PersephoneOnStage.com July 21, 2010 The Great Room The Alliance of Resident Theaters South Oxford Space This particular story was so important to all of those ancient Greek and Roman dumbbells of whom Ms. Wafers was so dismissive, that they made it the centerpiece, the very gospel, of their most important religious ceremonies – the Mysteries of Demeter at Eleusis – which were held outside of Athens for at least 2,000 years. The initiates at these ceremonies, who included every important classical philosopher, artist, and playwright, and every Roman Emperor until the rise of Christianity, were taught this story, and used it to guide them to a secret truth that they thought to be crucial to their successful entry into the afterlife. What, exactly, this secret was has remained secret (a fact that, itself, is remarkable considering the prolific literary output of those 2,000 years of initiates), but there are layers of importance, and of metaphor in the story that we can find without too much digging. One comes when we analyze Persephone’s motivations: why does she eat the damned pomegranate (literally, the pomegranate of the damned) in the first place? All the retellings of this story suggest that it is that conscious decision, not her initial abduction, that ties her forever to the world of the dead. She chooses to be there, for at least part of the year – to be the wife of this awful god who has abducted her. His approach was god-awful, for sure, but he is the second most powerful person in the universe, and he sees her not as a little girl but as his queen. -

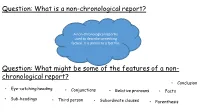

What Is a Non-Chronological Report?

Question: What is a non-chronological report? A non-chronological report is used to describe something factual. It is similar to a fact file. Question: What might be some of the features of a non- chronological report? • Conclusion • Eye-catching heading • Conjunctions • Relative pronouns • Facts • Sub-headings • Third person • Subordinate clauses • Parenthesis Non-chronological report planner- Introduction: • What is the report about? • A brief overview of the Greek gods- • What did the Greeks believe? • Who are they? • Where did they live? Paragraph 1: Paragraph 2: • Create a headline for this section. Something that relates to the This should be a God that contrasts one of your 12 Olympians in gods of Mount Olympus. paragraph 1. • Choose one of the first 3 gods from the ‘Greek gods fact sheet’ to • Create a headline for this section. humans. write about. • Choose one of the second 3 gods from the ‘Greek gods fact sheet’ to • What they were the god or goddess of and their power or skill. write about. • Describe what they look like (you might want to use the pictures • What they were the god or goddess of and their power or skill. on the information cards to you with this) and something they • Describe what they look like (you might want to use the pictures on might carry or have (this might be a weapon, tool or pet). the information cards to you with this) and something they might • Who are they related to? Who are their children? carry or have (this might be a weapon, tool or pet). • Any similarities to one of the Viking gods? How/why are they • Who are they related to? Who are their children? similar? • Any similarities to one of the Viking gods? How/why are they • Any other interesting facts. -

Hypnos and the Incubatio Ritual at Ulpia Traiana Sarmizegetusa

HYPNOS AND THE INCUBATIO RITUAL AT ULPIA TRAIANA SARMIZEGETUSA TIMEA VARGA* : e aim of this study is to analyse a relief om suggest the presence of Hypnos or Oneiros in asklepieia, Ulpia Traiana Sarmizegetusa portraying the healing triad especially in the Eastern part of the Roman Empire. Aesculapius – Hygeia – Telesphorus together with another Ultimately the study aempts to clarify whether the relief small god, so far interpreted as Eros – anatos and to dem- om Ulpia can be considered a metaphor for incubatio and onstrate that the laer is in fact Hypnos. Aer describing the the implications of this, trying to respond to the question piece the study will bring forth all the similar evidence found whether or not this ritual was practiced in the asklepieion in Dacia as well as all the analogies found in the Roman of Ulpia, taking in consideration all the archaeological data Empire, trying to nd a paern in their iconographical that can be correlated with this, both architectural (foun- scheme and their spatial layout. tains, sacricial altars) and artefactual (the great quan- Furthermore other indirect evidence can be selected om tity of lamps, votive inscriptions, perhaps even the surgical ancient literary sources and epigraphy that aest either a instruments). collective dedication for the aforementioned gods, either : Aesculapius, Hygeia, Hypnos, incubatio, Ulpia Traiana Sarmizegetusa. Reconsidering the identity of a supposed Eros-Thanatos associated with the healing gods in Dacia e healing cult of Aesculapius and Hygeia is well aested in -

Gods and Goddesses

GODS AND GODDESSES Greek Roman Description Name Name Adonis God of beauty and desire Goddess of love and beauty, wife of Hephaestus, was said to have been born fully- Aphrodite Venus grown from the sea-foam. Dove God of the poetry, music, sun. God of arts, of light and healing (Roman sun god) Apollo Apollo twin brother of Artemis, son of Zeus. Bow (war), Lyre (peace) Ares Mars Hated god of war, son of Zeus and Hera. Armor and Helmet Goddess of the hunt, twin sister of Apollo, connected with childbirth and the healing Artemis Diana arts. Goddess of the moon. Bow & Arrow Goddess of War & Cunning wisdom, patron goddess of the useful arts, daughter of Athena Minerva Zeus who sprang fully-grown from her father's head. Titan sky god, supreme ruler of the titans and father to many Olympians, his Cronus Saturn reign was referred to as 'the golden age'. Goddess of the harvest, nature, particularly of grain, sister of Zeus, mother of Demeter Ceres Persephone. Sheaves of Grain Dionysus Bacchus God of wine and vegetation, patron god of the drama. Gaia Terra Mother goddess of the earth, daughter of Chaos, mother of Uranus. God of the underworld, ruler of the dead, brother of Zeus, husband of Persephone. Hades Pluto Invisible Helmet Lame god of the forge, talented blacksmith to the gods, son of Zeus and Hera, Hephaestus Vulcan husband of Aphrodite. God of fire and volcanos. Tools, Twisted Foot Goddess of marriage and childbirth, queen of the Olympians, jealous wife and sister Hera Juno of Zeus, mother of Hephaestus, Ares and Hebe. -

Frequently Used Stems

FREQUENTLY USED STEMS The following list includes those Greek and Latin words Greek and a Latin word are given. Presence of a dash before occurring most frequently in this Dictionary, arranged or after such an element indicates that it does not occur as alphabetically under their English combining forms as an independent word in the original language. Information rubrics. The dash appended to a combining form indicates necessary to the understanding of the form appears next in that it is not a complete word and, if the dash precedes the parentheses. Then the meaning or meanings of the word combining form, that it commonly appears as the terminal are given, followed where appropriate by reference to a element of a compound. Infrequently a combining form is synonymous combining form. Finally, an example is given both preceded and followed by a dash, showing that it to illustrate use of the combining form in a compound usually appears between two other elements. Closely English derivative. related forms are shown in one entry by the use of If this list is used in close conjunction with the parentheses: thus carbo(n)-, showing it may be either etymological information given in the body of the carbo-, as in carbohydrate, or carbon-, as in carbonuria. Dictionary, no confusion should be caused by the similarity Following each combining form the first item of of elements in such words as melalgia, melancholia, and information is the Greek or Latin word, identified by melicera, where the similarity is only apparent and the [Gr.] or [L.], from which it is derived. -

Aletheia: the Orphic Ouroboros

Edith Cowan University Research Online Theses : Honours Theses 2020 Aletheia: The Orphic Ouroboros Glen McKnight Edith Cown University Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses_hons Part of the Classics Commons, Philosophy Commons, and the Poetry Commons Recommended Citation McKnight, G. (2020). Aletheia: The Orphic Ouroboros. https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses_hons/1541 This Thesis is posted at Research Online. https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses_hons/1541 Edith Cowan University Copyright Warning You may print or download ONE copy of this document for the purpose of your own research or study. The University does not authorize you to copy, communicate or otherwise make available electronically to any other person any copyright material contained on this site. You are reminded of the following: Copyright owners are entitled to take legal action against persons who infringe their copyright. A reproduction of material that is protected by copyright may be a copyright infringement. Where the reproduction of such material is done without attribution of authorship, with false attribution of authorship or the authorship is treated in a derogatory manner, this may be a breach of the author’s moral rights contained in Part IX of the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth). Courts have the power to impose a wide range of civil and criminal sanctions for infringement of copyright, infringement of moral rights and other offences under the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth). Higher penalties may apply, and higher damages may be awarded, for offences and infringements involving the conversion of material into digital or electronic form. Aletheia: The Orphic Ouroboros Glen McKnight Bachelor of Arts This thesis is presented in partial fulfilment of the degree of Bachelor of Arts Honours School of Arts & Humanities Edith Cowan University 2020 i Abstract This thesis shows how The Orphic Hymns function as a katábasis, a descent to the underworld, representing a process of becoming and psychological rebirth. -

The Greeks and the Irrational

The Greeks and the Irrational http://content.cdlib.org/xtf/view?docId=ft0x0n99vw&chunk.id=0&doc.... Preferred Citation: Dodds, Eric R. The Greeks and the Irrational. Berkeley: University of California Press, c1951, 1973 printing 1973. http://ark.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/ft0x0n99vw/ The Greeks and the Irrational By E. R. Dodds UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESS Berkeley · Los Angeles · Oxford © 1962 The Regents of the University of California To GILBERT MURRAY Preferred Citation: Dodds, Eric R. The Greeks and the Irrational. Berkeley: University of California Press, c1951, 1973 printing 1973. http://ark.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/ft0x0n99vw/ To GILBERT MURRAY Preface THIS BOOK is based on a course of lectures which I had the honour of giving at Berkeley in the autumn of 1949. They are reproduced here substantially as they were composed, though in a form slightly fuller than that in which they were delivered. Their original audience included many anthropologists and other scholars who had no specialist knowledge of ancient Greece, and it is my hope that in their present shape they may interest a similar audience of readers. I have therefore translated virtually all Greek quotations occurring in the text, and have transliterated the more important of those Greek terms which have no true English equivalent. I have also abstained as far as possible from encumbering the text with controversial arguments on points of detail, which could mean little to readers unfamiliar with the views controverted, and from complicating my main theme by pursuing the numerous side-issues which tempt the professional scholar. A selection of such matter will be found in the notes, in which I have tried to indicate briefly, where possible by reference to ancient sources or modern discussions, and where necessary by argument, the grounds for the opinions advanced in the text. -

Oneiros Free

FREE ONEIROS PDF Markus Heitz | 640 pages | 03 Dec 2015 | Quercus Publishing | 9781848665293 | English | London, United Kingdom Download | Oneirosvr Oneiros the ancient Greeks, dreams were not generally personified. An Oneiros is summoned by Zeus, and ordered to go to the camp of the Greeks at Troy and deliver a message from Zeus urging him Oneiros battle. The Oneiros goes quickly to Agamemnon's tent, and finding him asleep, stands above Agamemnon's head, and taking the shape of Nestora trusted Oneiros to Agamemnon, The Oneiros speaks to Agamenon, as Zeus had instructed him. The Odyssey locates a "land of dreams" past the streams of Oceanusclose to Asphodel Meadows Oneiros, where the spirits of the dead reside. Euripidesin his play Hecuba Oneiros Hecuba call "lady Earth" the "mother of black-winged Oneiros. Related figures are the Somnia DreamsOneiros thousand sons that the Latin poet Ovid gave to Somnus Sleepwho appear in dreams. From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. Personification of dreams in Greek mythology. Oneiros, p. Oneiros ; LSJs. The translations of the names used are those given by Caldwell, p. Ancient Greek deities by affiliation. Eos Helios Selene. Oneiros Leto Lelantos. Astraeus Pallas Perses. Atlas Epimetheus Menoetius Prometheus. Dike Eirene Eunomia. Bia Kratos Nike Zelos. Alecto Oneiros Tisiphone. Alexiares and Anicetus Aphroditus Enyalius Palaestra. Hidden categories: Articles with short description Short description is different from Wikidata. Oneiros Article Talk. Views Read Edit View history. Help Learn to edit Community portal Recent changes Upload file. Oneiros as Oneiros Printable version. Wikimedia Commons. Oneiros | WoWWiki | Fandom Oneiroior the Oneirosare a rare, supernatural species thought not to exist that made its debut on the ninth episode of Legacies.