Beyond Priesthood Religionsgeschichtliche Versuche Und Vorarbeiten

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Politics of Roman Memory in the Age of Justinian DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the D

The Politics of Roman Memory in the Age of Justinian DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Marion Woodrow Kruse, III Graduate Program in Greek and Latin The Ohio State University 2015 Dissertation Committee: Anthony Kaldellis, Advisor; Benjamin Acosta-Hughes; Nathan Rosenstein Copyright by Marion Woodrow Kruse, III 2015 ABSTRACT This dissertation explores the use of Roman historical memory from the late fifth century through the middle of the sixth century AD. The collapse of Roman government in the western Roman empire in the late fifth century inspired a crisis of identity and political messaging in the eastern Roman empire of the same period. I argue that the Romans of the eastern empire, in particular those who lived in Constantinople and worked in or around the imperial administration, responded to the challenge posed by the loss of Rome by rewriting the history of the Roman empire. The new historical narratives that arose during this period were initially concerned with Roman identity and fixated on urban space (in particular the cities of Rome and Constantinople) and Roman mythistory. By the sixth century, however, the debate over Roman history had begun to infuse all levels of Roman political discourse and became a major component of the emperor Justinian’s imperial messaging and propaganda, especially in his Novels. The imperial history proposed by the Novels was aggressivley challenged by other writers of the period, creating a clear historical and political conflict over the role and import of Roman history as a model or justification for Roman politics in the sixth century. -

Seven Churches of Revelation Turkey

TRAVEL GUIDE SEVEN CHURCHES OF REVELATION TURKEY TURKEY Pergamum Lesbos Thyatira Sardis Izmir Chios Smyrna Philadelphia Samos Ephesus Laodicea Aegean Sea Patmos ASIA Kos 1 Rhodes ARCHEOLOGICAL MAP OF WESTERN TURKEY BULGARIA Sinanköy Manya Mt. NORTH EDİRNE KIRKLARELİ Selimiye Fatih Iron Foundry Mosque UNESCO B L A C K S E A MACEDONIA Yeni Saray Kırklareli Höyük İSTANBUL Herakleia Skotoussa (Byzantium) Krenides Linos (Constantinople) Sirra Philippi Beikos Palatianon Berge Karaevlialtı Menekşe Çatağı Prusias Tauriana Filippoi THRACE Bathonea Küçükyalı Ad hypium Morylos Dikaia Heraion teikhos Achaeology Edessa Neapolis park KOCAELİ Tragilos Antisara Abdera Perinthos Basilica UNESCO Maroneia TEKİRDAĞ (İZMİT) DÜZCE Europos Kavala Doriskos Nicomedia Pella Amphipolis Stryme Işıklar Mt. ALBANIA Allante Lete Bormiskos Thessalonica Argilos THE SEA OF MARMARA SAKARYA MACEDONIANaoussa Apollonia Thassos Ainos (ADAPAZARI) UNESCO Thermes Aegae YALOVA Ceramic Furnaces Selectum Chalastra Strepsa Berea Iznik Lake Nicea Methone Cyzicus Vergina Petralona Samothrace Parion Roman theater Acanthos Zeytinli Ada Apamela Aisa Ouranopolis Hisardere Dasaki Elimia Pydna Barçın Höyük BTHYNIA Galepsos Yenibademli Höyük BURSA UNESCO Antigonia Thyssus Apollonia (Prusa) ÇANAKKALE Manyas Zeytinlik Höyük Arisbe Lake Ulubat Phylace Dion Akrothooi Lake Sane Parthenopolis GÖKCEADA Aktopraklık O.Gazi Külliyesi BİLECİK Asprokampos Kremaste Daskyleion UNESCO Höyük Pythion Neopolis Astyra Sundiken Mts. Herakleum Paşalar Sarhöyük Mount Athos Achmilleion Troy Pessinus Potamia Mt.Olympos -

Eunuchs in the East, Men in the West? 147

Eunuchs in the East, Men in the West? 147 Chapter 8 Eunuchs in the East, Men in the West? Dis/unity, Gender and Orientalism in the Fourth Century Shaun Tougher Introduction In the narrative of relations between East and West in the Roman Empire in the fourth century AD, the tensions between the eastern and western imperial courts at the end of the century loom large. The decision of Theodosius I to “split” the empire between his young sons Arcadius and Honorius (the teenage Arcadius in the east and the ten-year-old Honorius in the west) ushered in a period of intense hostility and competition between the courts, famously fo- cused on the figure of Stilicho.1 Stilicho, half-Vandal general and son-in-law of Theodosius I (Stilicho was married to Serena, Theodosius’ niece and adopted daughter), had been left as guardian of Honorius, but claimed guardianship of Arcadius too and concomitant authority over the east. In the political manoeu- vrings which followed the death of Theodosius I in 395, Stilicho was branded a public enemy by the eastern court. In the war of words between east and west a key figure was the (probably Alexandrian) poet Claudian, who acted as a ‘pro- pagandist’ (through panegyric and invective) for the western court, or rather Stilicho. Famously, Claudian wrote invectives on leading officials at the eastern court, namely Rufinus the praetorian prefect and Eutropius, the grand cham- berlain (praepositus sacri cubiculi), who was a eunuch. It is Claudian’s two at- tacks on Eutropius that are the inspiration and central focus of this paper which will examine the significance of the figure of the eunuch for the topic of the end of unity between east and west in the Roman Empire. -

Hadrian and the Greek East

HADRIAN AND THE GREEK EAST: IMPERIAL POLICY AND COMMUNICATION DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of the Ohio State University By Demetrios Kritsotakis, B.A, M.A. * * * * * The Ohio State University 2008 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Professor Fritz Graf, Adviser Professor Tom Hawkins ____________________________ Professor Anthony Kaldellis Adviser Greek and Latin Graduate Program Copyright by Demetrios Kritsotakis 2008 ABSTRACT The Roman Emperor Hadrian pursued a policy of unification of the vast Empire. After his accession, he abandoned the expansionist policy of his predecessor Trajan and focused on securing the frontiers of the empire and on maintaining its stability. Of the utmost importance was the further integration and participation in his program of the peoples of the Greek East, especially of the Greek mainland and Asia Minor. Hadrian now invited them to become active members of the empire. By his lengthy travels and benefactions to the people of the region and by the creation of the Panhellenion, Hadrian attempted to create a second center of the Empire. Rome, in the West, was the first center; now a second one, in the East, would draw together the Greek people on both sides of the Aegean Sea. Thus he could accelerate the unification of the empire by focusing on its two most important elements, Romans and Greeks. Hadrian channeled his intentions in a number of ways, including the use of specific iconographical types on the coinage of his reign and religious language and themes in his interactions with the Greeks. In both cases it becomes evident that the Greeks not only understood his messages, but they also reacted in a positive way. -

Loeb Lucian Vol5.Pdf

THE LOEB CLASSICAL LIBRARY FOUNDED BY JAMES LOEB, LL.D. EDITED BY fT. E. PAGE, C.H., LITT.D. litt.d. tE. CAPPS, PH.D., LL.D. tW. H. D. ROUSE, f.e.hist.soc. L. A. POST, L.H.D. E. H. WARMINGTON, m.a., LUCIAN V •^ LUCIAN WITH AN ENGLISH TRANSLATION BY A. M. HARMON OK YALE UNIVERSITY IN EIGHT VOLUMES V LONDON WILLIAM HEINEMANN LTD CAMBRIDGE, MASSACHUSETTS HARVARD UNIVERSITY PRESS MOMLXII f /. ! n ^1 First printed 1936 Reprinted 1955, 1962 Printed in Great Britain CONTENTS PAGE LIST OF LTTCIAN'S WORKS vii PREFATOEY NOTE xi THE PASSING OF PEBEORiNUS (Peregrinus) .... 1 THE RUNAWAYS {FugiUvt) 53 TOXARis, OR FRIENDSHIP (ToxaHs vd amiciHa) . 101 THE DANCE {Saltalio) 209 • LEXiPHANES (Lexiphanes) 291 THE EUNUCH (Eunuchiis) 329 ASTROLOGY {Astrologio) 347 THE MISTAKEN CRITIC {Pseudologista) 371 THE PARLIAMENT OF THE GODS {Deorutti concilhim) . 417 THE TYRANNICIDE (Tyrannicidj,) 443 DISOWNED (Abdicatvs) 475 INDEX 527 —A LIST OF LUCIAN'S WORKS SHOWING THEIR DIVISION INTO VOLUMES IN THIS EDITION Volume I Phalaris I and II—Hippias or the Bath—Dionysus Heracles—Amber or The Swans—The Fly—Nigrinus Demonax—The Hall—My Native Land—Octogenarians— True Story I and II—Slander—The Consonants at Law—The Carousal or The Lapiths. Volume II The Downward Journey or The Tyrant—Zeus Catechized —Zeus Rants—The Dream or The Cock—Prometheus—* Icaromenippus or The Sky-man—Timon or The Misanthrope —Charon or The Inspector—Philosophies for Sale. Volume HI The Dead Come to Life or The Fisherman—The Double Indictment or Trials by Jury—On Sacrifices—The Ignorant Book Collector—The Dream or Lucian's Career—The Parasite —The Lover of Lies—The Judgement of the Goddesses—On Salaried Posts in Great Houses. -

Greek Cities & Islands of Asia Minor

MASTER NEGATIVE NO. 93-81605- Y MICROFILMED 1 993 COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY LIBRARIES/NEW YORK / as part of the "Foundations of Western Civilization Preservation Project'' Funded by the NATIONAL ENDOWMENT FOR THE HUMANITIES Reproductions may not be made without permission from Columbia University Library COPYRIGHT STATEMENT The copyright law of the United States - Title 17, United photocopies or States Code - concerns the making of other reproductions of copyrighted material. and Under certain conditions specified in the law, libraries or other archives are authorized to furnish a photocopy the reproduction. One of these specified conditions is that for any photocopy or other reproduction is not to be "used purpose other than private study, scholarship, or for, or later uses, a research." If a user makes a request photocopy or reproduction for purposes in excess of fair infringement. use," that user may be liable for copyright a This institution reserves the right to refuse to accept fulfillment of the order copy order if, in its judgement, would involve violation of the copyright law. AUTHOR: VAUX, WILLIAM SANDYS WRIGHT TITLE: GREEK CITIES ISLANDS OF ASIA MINOR PLACE: LONDON DA TE: 1877 ' Master Negative # COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY LIBRARIES PRESERVATION DEPARTMENT BIBLIOGRAPHIC MTCROFORM TAR^FT Original Material as Filmed - Existing Bibliographic Record m^m i» 884.7 !! V46 Vaux, V7aiion Sandys Wright, 1818-1885. ' Ancient history from the monuments. Greek cities I i and islands of Asia Minor, by W. S. W. Vaux... ' ,' London, Society for promoting Christian knowledce." ! 1877. 188. p. plate illus. 17 cm. ^iH2n KJ Restrictions on Use: TECHNICAL MICROFORM DATA i? FILM SIZE: 3 S'^y^/"^ REDUCTION IMAGE RATIO: J^/ PLACEMENT: lA UA) iB . -

The Art and Artifacts Associated with the Cult of Dionysus

Alana Koontz The Art and Artifacts Associated with the Cult of Dionysus Alana Koontz is a student at University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee graduating with a degree in Art History and a certificate in Ancient Mediterranean Studies. The main focus of her studies has been ancient art, with specific attention to ancient architecture, statuary, and erotic symbolism in ancient art. Through various internships, volunteering and presentations, Alana has deepened her understanding of the art world, and hopes to do so more in the future. Alana hopes to continue to grad school and earn her Master’s Degree in Art History and Museum Studies, and eventually earn her PhD. Her goal is to work in a large museum as a curator of the ancient collections. Alana would like to thank the Religious Studies Student Organization for this fantastic experience, and appreciates them for letting her participate. Dionysus was the god of wine, art, vegetation and also widely worshipped as a fertility god. The cult of Dionysus worshipped him fondly with cultural festivities, wine-induced ritualistic dances, 1 intense and violent orgies, and secretive various depictions of drunken revelry. 2 He embodies the intoxicating portion of nature. Dionysus, in myth, was the last god to be accepted at Mt Olympus, and was known for having a mortal mother. He spent his adulthood teaching the cultivation of grapes, and wine-making. The worship began as a celebration of culture, with plays and processions, and progressed into a cult that was shrouded in mystery. Later in history, worshippers would perform their rituals in the cover of darkness, limiting the cult-practitioners to women, and were surrounded by myth that is sometimes interpreted as fact. -

The Collecting, Dealing and Patronage Practices of Gaspare Roomer

ART AND BUSINESS IN SEVENTEENTH-CENTURY NAPLES: THE COLLECTING, DEALING AND PATRONAGE PRACTICES OF GASPARE ROOMER by Chantelle Lepine-Cercone A thesis submitted to the Department of Art History In conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Queen’s University Kingston, Ontario, Canada (November, 2014) Copyright ©Chantelle Lepine-Cercone, 2014 Abstract This thesis examines the cultural influence of the seventeenth-century Flemish merchant Gaspare Roomer, who lived in Naples from 1616 until 1674. Specifically, it explores his art dealing, collecting and patronage activities, which exerted a notable influence on Neapolitan society. Using bank documents, letters, artist biographies and guidebooks, Roomer’s practices as an art dealer are studied and his importance as a major figure in the artistic exchange between Northern and Sourthern Europe is elucidated. His collection is primarily reconstructed using inventories, wills and artist biographies. Through this examination, Roomer emerges as one of Naples’ most prominent collectors of landscapes, still lifes and battle scenes, in addition to being a sophisticated collector of history paintings. The merchant’s relationship to the Spanish viceregal government of Naples is also discussed, as are his contributions to charity. Giving paintings to notable individuals and large donations to religious institutions were another way in which Roomer exacted influence. This study of Roomer’s cultural importance is comprehensive, exploring both Northern and Southern European sources. Through extensive use of primary source material, the full extent of Roomer’s art dealing, collecting and patronage practices are thoroughly examined. ii Acknowledgements I am deeply thankful to my thesis supervisor, Dr. Sebastian Schütze. -

Yarrr! the Pirate’S Guide to R 6

2dr. nathaniel d. phillips YaRr! The Piate’s Guide to R DR. NATHANIEL D. PHILLIPS YARRR! THE PIRATE’S GUIDE TO R 6 10: Plotting: Part Deux 157 Advanced colors 157 Plot margins 162 Arranging multiple plots with par(mfrow) and layout 163 Additional Tips 166 11: Inferential Statistics: 1 and 2-sample Null-Hypothesis tests 167 Null vs. Alternative Hypotheses, Descriptive Statistics, Test Statistics, and p-values: A very short introduction 168 Null v Alternative Hypothesis 168 Hypothesis test objects – htest 172 T-test with t.test() 174 Correlation test with cor.test() 178 Chi-square test 181 Getting APA-style conclusions with the apa function 183 Test your R might! 185 12: ANOVA and Factorial Designs 187 Between-Subjects ANOVA 188 4 Steps to conduct a standard ANOVA in R 190 y x1 * x2 194 ANOVA with interactions: ( ⇠ ) Additional tips 197 Test your R Might! 200 13: Regression 201 The Linear Model 201 Linear regression with lm() 201 Estimating the value of diamonds with lm() 202 Including interactions in models: dv x1 *x2 206 ⇠ Comparing regression models with anova() 208 Regression on non-Normal data with glm() 211 7 Getting an ANOVA from a regression model with aov() 214 Additional Tips 215 Test your Might! A ship auction 217 14: Writing your own functions 219 Why would you want to write your own function? 219 The basic structure of a function 220 Additional Tips 225 Test Your R Might! 230 15: Loops 231 What are loops? 232 Creating multiple plots with a loop 235 Updating objects with loop results 236 Loops over multiple indices 237 When and -

Webfile121848.Pdf

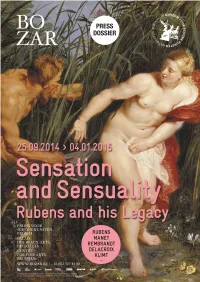

0 TABLE OF CONTENTS Press release ................................................................................................................................................... 2 Catalogue text: Nico Van Hout - Curator ...................................................................................................... 6 Gallery texts ................................................................................................................................................... 11 Transversal Activities ................................................................................................................................... 14 BOZAR MUSIC ......................................................................................................................................... 14 BOZAR LITERATURE ............................................................................................................................. 17 BOZAR EXPO ........................................................................................................................................... 17 BOZAR CINEMA ...................................................................................................................................... 18 Rubens for families ...................................................................................................................................... 19 Disovery trails for families (6>12) ........................................................................................................... 19 -

View / Download 2.4 Mb

Lucian and the Atticists: A Barbarian at the Gates by David William Frierson Stifler Department of Classical Studies Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ William A. Johnson, Supervisor ___________________________ Janet Downie ___________________________ Joshua D. Sosin ___________________________ Jed W. Atkins Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Classical Studies in the Graduate School of Duke University 2019 ABSTRACT Lucian and the Atticists: A Barbarian at the Gates by David William Frierson Stifler Department of Classical Studies Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ William A. Johnson, Supervisor ___________________________ Janet Downie ___________________________ Joshua D. Sosin ___________________________ Jed W. Atkins An abstract of a dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Classical Studies in the Graduate School of Duke University 2019 Copyright by David William Frierson Stifler 2019 Abstract This dissertation investigates ancient language ideologies constructed by Greek and Latin writers of the second and third centuries CE, a loosely-connected movement now generally referred to the Second Sophistic. It focuses on Lucian of Samosata, a Syrian “barbarian” writer of satire and parody in Greek, and especially on his works that engage with language-oriented topics of contemporary relevance to his era. The term “language ideologies”, as it is used in studies of sociolinguistics, refers to beliefs and practices about language as they function within the social context of a particular culture or set of cultures; prescriptive grammar, for example, is a broad and rather common example. The surge in Greek (and some Latin) literary output in the Second Sophistic led many writers, with Lucian an especially noteworthy example, to express a variety of ideologies regarding the form and use of language. -

Arrian's Voyage Round the Euxine

— T.('vn.l,r fuipf ARRIAN'S VOYAGE ROUND THE EUXINE SEA TRANSLATED $ AND ACCOMPANIED WITH A GEOGRAPHICAL DISSERTATION, AND MAPS. TO WHICH ARE ADDED THREE DISCOURSES, Euxine Sea. I. On the Trade to the Eqft Indies by means of the failed II. On the Di/lance which the Ships ofAntiquity ufually in twenty-four Hours. TIL On the Meafure of the Olympic Stadium. OXFORD: DAVIES SOLD BY J. COOKE; AND BY MESSRS. CADELL AND r STRAND, LONDON. 1805. S.. Collingwood, Printer, Oxford, TO THE EMPEROR CAESAR ADRIAN AUGUSTUS, ARRIAN WISHETH HEALTH AND PROSPERITY. We came in the courfe of our voyage to Trapezus, a Greek city in a maritime fituation, a colony from Sinope, as we are in- formed by Xenophon, the celebrated Hiftorian. We furveyed the Euxine fea with the greater pleafure, as we viewed it from the lame fpot, whence both Xenophon and Yourfelf had formerly ob- ferved it. Two altars of rough Hone are ftill landing there ; but, from the coarfenefs of the materials, the letters infcribed upon them are indiftincliy engraven, and the Infcription itfelf is incor- rectly written, as is common among barbarous people. I deter- mined therefore to erect altars of marble, and to engrave the In- fcription in well marked and diftinct characters. Your Statue, which Hands there, has merit in the idea of the figure, and of the defign, as it reprefents You pointing towards the fea; but it bears no refemblance to the Original, and the execution is in other re- fpects but indifferent. Send therefore a Statue worthy to be called Yours, and of a fimilar delign to the one which is there at prefent, b as 2 ARYAN'S PERIPLUS as the fituation is well calculated for perpetuating, by thefe means, the memory of any illuftrious perfon.