Interview with Thomas Buergenthal January 29, 1990 RG-50.030*0046 PREFACE

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

April 2021 Volume 46 No

mars og april 2021 Volume 46 No. 2 Fosselyngen Lodge No. 5-082, Sons of Norway PO Box 20957, Milwaukee, WI 53220 FOSSELYNGEN LODGE – CALENDAR OF EVENTS For each of the following Zoom meetings, an email with the Zoom invitation will be sent approximately three days before the meeting. If you do not receive an invitation and want to join us, please contact Sue at 414-526-8312 or [email protected] . MARCH 8 Monday Virtual Lodge Social Meeting & Program for All Members via Zoom @ 7PM. Program: “Coming Home”: Documentary Video About Kayaking on Fjords In Norway We will see the 25 minute documentary, “Coming Home”, by adventurer-author- speaker David Ellingson, about his one month kayak adventure on the Sogne and Hardanger Fjords in Norway. David will join our Zoom meeting to answer our questions. David will also talk about his book, “Paddle Pilgrim: Kayaking the Fjords of Norway.” APRIL 12 Monday Virtual Lodge Social Meeting & Program for All Members via Zoom @ 7PM. Program: Presentation via Zoom by Timothy Boyce About Odd Nansen’s . Secret Diary Written in a World War II Concentration Camp See a more detailed description of the program on Page 3. MAY 10 Monday Virtual Lodge Meeting for All Members via Zoom @ 7PM. Put on your calendar. See May/June 2021 Runespeak for details. Contents of This Issue: Pg. 1: Calendar of Events; Table of Contents Pg. 2: President’s Report; Officers Pg. 3: April 12th Program by Timothy Boyce RE: Odd Nansen; Story of Nina Hasvoll; Mr. Boyce’s Blog Pg. 4: Sympathy; King Harold’s 84th Birthday; 7 Nordic-Inspired Ways to Celebrate Spring Pg. -

Masarykova Univerzita Filozofická Fakulta Brno 2013

Masarykova univerzita Filozofická fakulta Ústav germanistiky, nordistiky a nederlandistiky Eva Dohnálková Nansenhjelpens historie og aktiviteter. En norsk humanitær organisasjon i tsjekkisk perspektiv. Magisterská diplomová práce Vedoucí práce: doc. PhDr. Miluše Juříčková, CSc. Brno 2013 Prohlašuji, že jsem diplomovou práci vypracovala samostatně s využitím uvedených pramenů a literatury. …………………………………………….. Podpis autora práce 2 Innholdsliste 1 Innledning.............................................................................................................................4 1.1 Oppgavens utgangspunkt og problemstilling.....................................................................4 1.2 Avgrensning av oppgaven..................................................................................................5 1.3 Oppgavens oppbygging.....................................................................................................5 1.4 Kilder.................................................................................................................................6 2 Jøder i Norge........................................................................................................................7 2.1 Fra vikingtiden til året 1899...............................................................................................7 2.2 Fra 1900 til 1939 ...............................................................................................................9 2.2.1 Det jødiske barnehjemmet............................................................................................10 -

Enslige Asylbarn Og Historiens Tvetydighet1

Barn nr. 3-4 2007:41–58, ISSN 0800–1669 © 2007 Norsk senter for barneforskning Enslige asylbarn og historiens tvetydighet1 Ketil Eide Sammendrag Denne artikkelen aktualiserer hvilke samfunnsmessige og omsorgspolitiske dilemmaer som oppstår i det norske samfunnet når det ankommer barn som er uten sine foreldres nære om- sorg og beskyttelse – barn som har en annerledes kulturell og etnisk bakgrunn, og som er flyktninger fra samfunn preget av væpnede konflikter eller annen organisert vold. Artikkelen fokuserer på hvordan samfunnet har oppfattet disse barnas situasjon på ulike tidspunkt og under ulike historiske omstendigheter, og hvilken praksis som har blitt utøvet når det gjelder mottak og omsorg. Den aktuelle historiske perioden er fra 1938 og fram mot år 2000. Utval- get består av fire grupper av flyktningbarn som kom til Norge uten sine foreldre.2 Disse fire utvalgene er jødiske barn som ankom 1938–39, ungarske barn som kom i 1956, tibetanske barn som kom i 1964, og enslige mindreårige flyktninger med ulik etnisk bakgrunn som kom i perioden 1989–92.3 1 Denne artikkelen bygger på avhandlingen: Tvetydige barn. Om barnemigranter i et historisk komparativt perspektiv. Universitetet i Bergen/IMER (Eide 2005). 2 Datamaterialet består av historiske dokumenter og 34 intervjuer med representanter fra de fire utvalgene, i tillegg til 19 intervjuer av hjelpere og beslutningstakere. Intervjuene er fore- tatt i perioden 1999–2002. De ulike utvalgene er ikke kronologisk framstilt i denne artikke- len, og de er også ulikt vektlagt i framstillingen. Dette er bevisst gjort uti fra hvilken tematikk som artikkelen aktualiserer. For mer detaljer om de fire utvalgene og metodisk tilnærming vises til avhandling (Eide 2005). -

About Odd Nansen

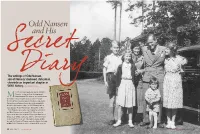

Odd Nansen and His The writings of Odd Nansen, June 1945: Odd nansen is reunited with his family son of Norway’s beloved statesman, after WWII. chronicle an important chapter in WWII history. By Timothy J. Boyce ost Norwegian-Americans know of Fridtjof Nansen—polar explorer, statesman and M humanitarian. His memory and achievements are widely celebrated in Norway, as attested by the October 2011 sesquicentennial celebration of his birth. But far fewer in America know about the remarkable y L life and achievements of his son, Odd Nansen, and in i M FA s particular his World War II diary, “From Day to Day.” ’ Odd Nansen, the fourth of five children of Fridtjof NANSEN and Eva Nansen, was born in 1901. He received a f ODD f O degree in architecture from the Norwegian Institute of esy rt u Technology (NTH), and from 1927 to 1930 lived and O PH c PH a worked in New York City. His father’s failing health R g brought Odd back to Norway, and after Fridtjof’s death PHOTO in May 1930 Nansen decided to remain. Following in 16 Viking May 2013 sonsofnorway.com sonsofnorway.com Viking May 2013 17 Nansen never intended to publish the diary, Fridtjof’s humanitarian secret diary, recording his From Day to Day Norwegians arrested during His entries also reveal but wrote it simply as a way to communicate with footsteps, Odd Nansen experiences, hopes, dreams The diary, later published the war, almost 7,500 were the quiet strength, and his wife Kari, and as a means of sorting out his helped establish and fears. -

From Day to Day: One Man’S Diary of Survival in Nazi Concentration Camps by Odd Nansen, Edited and Annotated by Timothy J

BOOKS From Day to Day: One Man’s Diary of Survival in Nazi Concentration Camps by Odd Nansen, Edited and annotated by Timothy J. Boyce Vanderbilt University Press, 2016 Review by Amy Scheibe hen Odd Nansen was As the inevitable deportation to Germany 21, his father won the approaches, his resolve to remain optimistic Nobel Peace Prize, and feels painfully jejune. the surname “Nansen”— Heightening the sense of dread are the already a household name brilliant footnotes that embellish the diary. By in Norway—became world placing them on the page with Nansen’s entries, renowned. Besides being Timothy J. Boyce skilfully enhances this history recognised for his heroic with enriching detail. efforts post-WWI and the Once in Germany, Nansen realises that creation of the “Nansen only through writing and drawing can he Passport” for refugees, make sense of the banal cruelty, to order it, Fridtjof Nansen was also and then let it fall from his memory so he an intrepid explorer who famously crossed doesn’t carry it into the next terrible day. Greenland on skis. By doing so he creates a kind of literary WOdd Nansen could have let this paternal transference—relinquishing his despair Heightening the sense of dread monolith eclipse his life. Instead, he forged to his diary and pushing his half-full glass his own humanitarian path by tirelessly of incremental survival back up the hill of are the brilliant advocating on behalf of refugees—in particular German insanity. Being Norwegian, and footnotes Slovakian Jews—in the years leading up to a sort of celebrity, his personal treatment that embellish WWII. -

POLHØGDA POLHØGDA from the Home of Fridtjof Fra Fridtjof Nansens Bolig Til Nansen to the Fridtjof Nansen Fridtjof Nansens Institutt Institute Av Ivar M

POLHØGDA POLHØGDA From the Home of Fridtjof Fra Fridtjof Nansens bolig til Nansen to the Fridtjof Nansen Fridtjof Nansens Institutt Institute av Ivar M. Liseter by Ivar M. Liseter 1 Fridtjof Nansen. Portrett tatt I London I 1893, like før han la ut på Framferden. Fridtjof Nansen. Potrait taken in London in 1893, just before he set in the Fram for the Arctic Sea. FRIDTJOF NANSEN Fridtjof Nansen (1861-1930) became Fridtjof Nansen (1861-1930) ble berømt famous in the 1880s and ’90s for his daring i 1880- og 90-årene for sine dristige expeditions across Greenland and the Arctic ekspedisjoner over Grønland og Polhavet. Ocean. In Norway, a nation then striving for I Norge, som den gang strebet mot independence, he became a national symbol selvstendighet, ble han et nasjonalt symbol and idol, but his fame travelled far and og et ideal, men hans berømmelse var wide. He described his expeditions in many internasjonal. Han beskrev sine ekspedisjoner books, often with his own illustrations, which i en rekke bøker som ble bestselgere i mange became bestsellers in many countries, and land, og han gjennomførte omfattende made extensive lecture tours in Europe and foredragsturneer i Europa og Amerika. America. His international contacts enabled Hans internasjonale kontakter satte ham him to play a key part in the successful i stand til å spille en betydelig rolle i Norges dissolution of the union between Sweden vellykkede løsrivelse fra unionen med Sverige and Norway in 1905, and he served as i 1905, og han tjenestegjorde som det independent Norway’s first ambassador to selvstendige Norges første ambassadør til the United Kingdom. -

An Anti-‐Semitic Slaughter Law? the Origins of the Norwegian

Andreas Snildal An Anti-Semitic Slaughter Law? The Origins of the Norwegian Prohibition of Jewish Religious Slaughter c. 1890–1930 Dissertation for the Degree of Philosophiae Doctor Faculty of Humanities, University of Oslo 2014 2 Acknowledgements I would like to extend my gratitude to my supervisor, Professor Einhart Lorenz, who first suggested the Norwegian controversy on Jewish religious slaughter as a suiting theme for a doctoral dissertation. Without his support and guidance, the present dissertation could not have been written. I also thank Lars Lien of the Center for Studies of the Holocaust and Religious Minorities, Oslo, for generously sharing with me some of the source material collected in connection with his own doctoral work. The Department of Archaeology, Conservation and History has offered me excellent working conditions for three years, and I would thank in particular Professor Gro Hagemann for encouragement and not least for thought-provoking thesis seminars. A highlight in this respect was the seminar that she arranged at the Centre Franco-Norvégien en Sciences Sociales et Humaines in Paris in September 2012. I would also like to thank the Centre and its staff for having hosted me on other occasions. Fellow doctoral candidates at the Department of Archaeology, Conservation and History have made these past three years both socially and scholarly stimulating. In this regard, I am indebted particularly to Chalak Kaveh and Margaretha Adriana van Es, whose comments on my drafts have been of great help. ‘Extra- curricular’ projects conducted together with friends and former colleagues Ernst Hugo Bjerke and Tor Ivar Hansen have been welcome diversions from dissertation work. -

Oslo Architecture Guide 2020

WHAT Architect WHERE Notes Zone 1: Gamle Oslo + Sentrum (City Center) The award-winning buildings Schweigaardsgate 21 and 23 were designed as one architectural composition. Each of the two buildings completed in 2013, volumes appears as almost perfectly cubic shapes. Within each there is a glazed atrium that provides daylight into the office floors. The office plans are mainly based on a U-shape, where the central Schweigaardsgate 21 Lund+Slaatto *** atrium opens towards the main road on the lower floors, and then as + 23 Architects Schweigaards gate 21 on ascends up the space rotates incrementally toward the opposite direction and the view out over the main railway station to the south. The two buildings were given distinct characters in the facade cladding. Both buildings are clad in granite, but on S21 the stone is light grey, while on S23 it is almost black. This eleven-story building completed in 2016 is the last of BARCODE’s 13 buildings to be completed and the farthest to the east. Built on a narrow wedge-shaped lot, the building’s offices are only 5–10 metres wide. Each floor has meeting rooms cantilevered out over the eastern The Wedge Office *** A-Lab Dronning Eufemias façade, a space-saving feature that adds a lively architectonic quality. Building gate 42 An exterior stairway / fire escape zigzags between these meeting- room boxes, further enhancing the building’s iconic sculptural expression – facing the Mediaeval Park and the City of Oslo to the east, this is a fitting conclusion to BARCODE’s long row of façades. DNB Bank Headquarters, completed in 2012, expresses both the transparency and stability of DNB as a modern financial institution. -

Two Art Exhibitions As Dialogic Events in the History of Czech-Norwegian Cultural Relations

2019 ACTA UNIVERSITATIS CAROLINAE PAG. 121–127 PHILOLOGICA 4 / GERMANISTICA PRAGENSIA TWO ART EXHIBITIONS AS DIALOGIC EVENTS IN THE HISTORY OF CZECH-NORWEGIAN CULTURAL RELATIONS MILUŠE JUŘÍČKOVÁ ABSTRACT The article analyses two art exhibitions in the context of Czech-Norwe- gian relations, presenting both the Czechoslovak book exhibition in Oslo (1937) and the Norwegian painting and applied art exhibition in Prague (1938) as important parts in a bilateral cultural dialogue. The promising initial communication in form of a mutual information exchange was soon disrupted by the beginning of World War II and post-war politics. Keywords: Czech-Norwegian relations; cultural transfer; exhibition events; Olav Rytter; Czech literature; cultural diplomacy Transnational cultural transfer is carried out on a large scale in a variety of communi- cation forms, the most basic being translation events and reception processes of fiction and nonfiction literary texts. This article investigates some significant communication mechanisms in two art exhibitions, understood and denoted as representative perfor- mances of two countries in a concrete period, in the years 1937–1938. The Czech-Norwegian relationship can be characterised as asymetrical in a particular aspect: the number of translated texts translated from Norwegian into Czech in the last 150 years has been several times higher than those translated from Czech into Norwegian (Kilsti 2010, 258). The general interest in mutual cultural exchange has also been distinct- ly greater on the Czech side, taking into account the quantity of epitexts of various genres, such as book reviews and literary critics texts. The complex reasons for this imbalance are beyond the scope of this article. -

The Law School Community Looks Forward to Sup·Porte : Verb Welcoming You Back to Washington Square

Cahill Gordon & Reindel LLP Cravath, Swaine & Moore LLP Paul, Weiss, Rifkind, W The good from evil Auschwitz survivor Thomas Law School & Garrison LLP Sullivan & Cromwell LLP Wachtell, Lipton, Rosen & Katz Weil, Gots Buergenthal ’60 has spent his life Willkie Farr & Gallagher LLP Make your mark. Fried, Frank, Harris, Shriver & Jac The avenging injustice with justice. a new legal movement Empirical Legal Studies uses Cahill Gordon & Reindel LLP These firms did. Cravath, Swaine & Moore LLP | THE MAGAZINE OF THE NEW YORK UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF LAW OF SCHOOL UNIVERSITY YORK NEW THE OF MAGAZINE THE quantitative data to analyze Rifkind, Wharton & Garrison LLP Sullivan & Cromwell LLP Wachtell, Lipton, Rosen Lawthe magazine of the new york School university school of law • autumn 2008 thorny public policy problems. al & Manges LLP Cahill Gordon & Reindel LLP Willkie Farr & Gallagher Garrison LLP Cravath, Swaine & Moore LLP Weil, Gotshal & Manges LLP Wa illkie Farr & Gallagher LLP Fried, Frank, Harris, Shriver & Jacobson LLP Paul Weiss & Reindel LLP Paul, Weiss, Rifkind, Wharton & Garrison LLP Cravath,Swaine arton & Garrison LLP Sullivan & Cromwell LLP Cahill Gordon & Reindel LLP & Katz Weil, Gotshal & Manges LLP Wachtell, Lipton, Rosen & Katz Willkie Farr & Cravath, Swaine & Moore LLP Weil, Gotshal & Manges LLP Paul, Weiss, Rifkind, & Manges LLP Willkie Farr & Gallagher LLP Sullivan & Cromwell LLP Wacht Fried, Frank, Harris, Shriver & Jacobson LLP Willkie Farr & Gallagher LLP Cahill & aul, Weiss, Rifkind, Wharton & Garrison LLP Sullivan & CromwellThe Wall LLP of HonorWachtell, Gordon & Reindel LLP Wachtell, Lipton, Rosen & Katz WillkieTo find Farr out what & your Gallagher firm can do LLP to be acknowledged on the & Reindel LLP Cravath, Swaine & Moore LLP Paul, Weiss, Rifkind,Wall of Honor, Wharton please contact & Garri Marsha Metrinko at (212) 998-6485 or Sullivan & Cromwell LLP Wachtell, Lipton, Rosen & Katz Weil,[email protected]. -

Hurra for Syttende Mai!! Gail 5 Pictures of Past Syttende Mai Parades in Bay Ridge, Brooklyn, NY

3D Third District Today May 2016 Happy Syttende Mai Happy Memorial Day Happy Mother’s Day Support the Charitable Trust Published by Ron Martinsen, 3D Pub. Rel. Dir. 3D SofN Facebook Page https://www.facebook.com/TheThirdDistrictoftheSonsofNorway 1 The mission of Sons of Norway is to promote and to preserve the heritage and culture of Norway, to celebrate our relationship with other Nordic countries, and to provide quality insurance and financial products to its members. Fra Presidenten, Mary B. Andersen, May 2016 It is time to get down to business “Cumulatively small decisions, choices, actions, make a very big difference” Jane Goodall As can be expected at this time, your Third District Board and many of your fraternal brothers and sisters serving on convention committees are busy getting ready for the 64th District Lodge meeting to be held in June at Myrtle Beach, South Carolina. This location was specifically chosen to enable as many lodges as possible to attend. Each delegate makes a difference. The delegates set the course for the future direction of the Third District! You have a voice; I hope your lodge will use it by sending delegates. Lodge delegates will receive a Convention Reports book in late April or early May via email. It is the delegate’s job to discuss the various resolutions with his/her respective lodge and understand how the lodge wants the delegate to vote on a particular issue. I can’t emphasize enough this is your lodge’s time to officially voice your thoughts and wishes on the future of the Third District! Please, try to take advantage of this opportunity. -

Nansenhjelpens Historie Og Aktiviteter. En Norsk Humanitær Organisasjon I Tsjekkisk Perspektiv

BRÜNNER BEITRÄGE ZUR GERMANISTIK UND NORDISTIK 28 / 2014 / 1–2 EVA DOHNÁLKOVÁ NANSENHJELPENS HISTORIE OG AKTIVITETER. EN NORSK HUMANITÆR ORGANISASJON I TSJEKKISK PERSPEKTIV Abstract: This article deals with the Norwegian humanitarian organisation Nansenhjelpen and is based on master theses defended in January 2014 at Faculty of Arts at Masaryk University in Brno. The article focuses mainly on the activities of the organisation in Czechoslovakia as this topic has been rarely discussed so far. Partner organisation on Czech side are shortly presented, but the article describes mainly a rescue campaign of Nansenhjelpen in which a group of about 37 children was transported from Czechoslovakia to Norway. Children were placed in foster families or the jewish children’s home in Oslo. Some of the children were however sent back to Czechoslovakia on their parents’ demand and 14 of remaining children later fled to Sweden. Key words: Norway; Nansenhjelpen; World War II; humanitarian organisation; Odd Nansen; Tove Filseth Hensikten med denne artikkelen er å presentere en norsk humanitær organisa- sjon Nansenhjelpen som ble stiftet i Norge i 1937 på initiativ av Odd Nansen for å hjelpe flyktninger. Teksten er et sammendrag av masteravhandlingen som ble forsvart i januar 2014 på Det filosofiske fakultetet i Brno. Nansenhjelpen var en av de få organisasjonene som konsentrerte seg om jødis- ke flyktninger under andre verdenskrig. Jødene ble ikke anerkjent som politiske flyktninger i Norge på den tiden og staten var derfor ikke villig til å ta dem imot. Hjelpeaktiviteter for jødene ble derfor enda vanskeligere å gjennomføre enn hjel- peaksjonene rettet mot vanlige, ikke-jødiske, flyktninger.