Houses and Barns

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ARKIV: Hele Byens Hukommelse HELE BYENS HUKOMMELSE Tobias Hilde Barstad, Direktør I Kulturetaten

TIDSSKRIFT FOR OSLOHISTORIE 2015 tobias PRIVAT- ARKIV: Hele byens hukommelse HELE BYENS HUKOMMELSE tobias Hilde Barstad, direktør i Kulturetaten Gjennom hele livet setter vi mennesker spor etter oss, i møte med det offentlige, med privat sektor som organisasjoner, bedrifter eller private institusjoner, og i helt personlige dokumenter. I det offentlige blir slike spor gjerne varige i form av arkiver, mens privat sektor setter lite spor i arkivene. Men samfunnsutviklingen skjer i et samspill mellom offentlig og privat TOBIAS er Oslo byarkivs eget sektor, og privatarkiv er derfor viktig for å dokumentere hele samfunnet. fagtidsskrift om oslohistorie, De private arkivene trengs! arkiv og arkivdanning. I dag er vernet av privatarkiv for svakt. Det blir spesielt tydelig når det Tidsskriftet presenterer viktige, private utfører tjenester for det offentlige. Når kommunen plasserer barn på nytenkende og spennende en kommunal barnevernsinstitusjon, stiller loven krav om at oppholdet skal artikler, og løfter fram godbiter dokumenteres. Men om kommunen plasserer barnet på en privat barne - fra det rike kildematerialet i vernsinstitusjon, stiller ikke loven like strenge krav, og det kan være tilfeldig Byarkivet. Navnet Tobias hvilken dokumentasjon som blir tatt vare på. Det kan gi svært ulike vilkår for kommer fra den tiden da By- barn som i ettertid vil finne ut av sin egen historie. arkivet holdt til i ett av rådhus- Byarkivets oppgave er å bevare arkiver som tilsammen gir et helhetlig tårnene og fikk kallenavn etter bilde av samfunnet. Vi samler derfor inn også private arkiver i Oslo. Bare Tobias i tårnet fra Torbjørn slik kan vi sikre at vi er hele byens hukommelse. -

April 2021 Volume 46 No

mars og april 2021 Volume 46 No. 2 Fosselyngen Lodge No. 5-082, Sons of Norway PO Box 20957, Milwaukee, WI 53220 FOSSELYNGEN LODGE – CALENDAR OF EVENTS For each of the following Zoom meetings, an email with the Zoom invitation will be sent approximately three days before the meeting. If you do not receive an invitation and want to join us, please contact Sue at 414-526-8312 or [email protected] . MARCH 8 Monday Virtual Lodge Social Meeting & Program for All Members via Zoom @ 7PM. Program: “Coming Home”: Documentary Video About Kayaking on Fjords In Norway We will see the 25 minute documentary, “Coming Home”, by adventurer-author- speaker David Ellingson, about his one month kayak adventure on the Sogne and Hardanger Fjords in Norway. David will join our Zoom meeting to answer our questions. David will also talk about his book, “Paddle Pilgrim: Kayaking the Fjords of Norway.” APRIL 12 Monday Virtual Lodge Social Meeting & Program for All Members via Zoom @ 7PM. Program: Presentation via Zoom by Timothy Boyce About Odd Nansen’s . Secret Diary Written in a World War II Concentration Camp See a more detailed description of the program on Page 3. MAY 10 Monday Virtual Lodge Meeting for All Members via Zoom @ 7PM. Put on your calendar. See May/June 2021 Runespeak for details. Contents of This Issue: Pg. 1: Calendar of Events; Table of Contents Pg. 2: President’s Report; Officers Pg. 3: April 12th Program by Timothy Boyce RE: Odd Nansen; Story of Nina Hasvoll; Mr. Boyce’s Blog Pg. 4: Sympathy; King Harold’s 84th Birthday; 7 Nordic-Inspired Ways to Celebrate Spring Pg. -

Masarykova Univerzita Filozofická Fakulta Brno 2013

Masarykova univerzita Filozofická fakulta Ústav germanistiky, nordistiky a nederlandistiky Eva Dohnálková Nansenhjelpens historie og aktiviteter. En norsk humanitær organisasjon i tsjekkisk perspektiv. Magisterská diplomová práce Vedoucí práce: doc. PhDr. Miluše Juříčková, CSc. Brno 2013 Prohlašuji, že jsem diplomovou práci vypracovala samostatně s využitím uvedených pramenů a literatury. …………………………………………….. Podpis autora práce 2 Innholdsliste 1 Innledning.............................................................................................................................4 1.1 Oppgavens utgangspunkt og problemstilling.....................................................................4 1.2 Avgrensning av oppgaven..................................................................................................5 1.3 Oppgavens oppbygging.....................................................................................................5 1.4 Kilder.................................................................................................................................6 2 Jøder i Norge........................................................................................................................7 2.1 Fra vikingtiden til året 1899...............................................................................................7 2.2 Fra 1900 til 1939 ...............................................................................................................9 2.2.1 Det jødiske barnehjemmet............................................................................................10 -

Roš Chodeš Září 2016

Kè 20,– 5776 ZÁØÍ 2016 ROÈNÍK 78 AV ELUL VÌSTNÍK ŽIDOVSKÝCH NÁBOŽENSKÝCH OBCÍ V ÈESKÝCH ZEMÍCH A NA SLOVENSKU Obálka Friedricha Feigla k výboru z pražských nìmeckých básníkù. (K textu Oko vidí svìt na stranách 14–15.) 2 VÌSTNÍK 9/2016 KAMENY ZMIZELÝCH VÝLET ZA EMOCEMI Také v Liberci budou památku obìtí šoa Bouøi rozhoøèených reakcí sklidil v èes- pøipomínat tzv. kameny zmizelých. Ve kém prostøedí i v zahranièí autobus, pole- druhé polovinì èervence se zde bìhem AKTUALITY pený køiklavými reklamami lákajícími do jednoho dne konalo nìkolik slavnost- Osvìtimi na „výlet za emocemi“. Upozor- ních uložení a odhalení devatenácti mo- nila na nìj i média v Izraeli, v Británii èi sazných desek, zapuštìných do chodní- v Polsku a své znechucení nad ním vyjád- kù místních ulic a námìstí. øili mnozí pøeživší holokaust. Iniciátorem Kameny zmizelých navazují na pro- a autorem reklam nebyl majitel autobusu jekt „Stolpersteine“, který zahájil pøed sám, nýbrž známý èeský filmaø-dokumen- více jak pìtadvaceti lety nìmecký vý- tarista Vít Klusák, jemuž autobus poslou- tvarník Günter Demnig a který se úspìš- žil do pøipravovaného filmu z prostøedí nì rozšíøil do vìtšiny evropských zemí. èeského neonacismu. Klusák tvrdí, že V Èeské republice jej však v poslední chtìl upozornit na hloupý a bulvární zpù- dobì provázely technické a organizaèní sob, jakým cestovky lákají turisty do míst problémy, a proto se nìkteré naše obce Program: spojených s touto temnou kapitolou dìjin, rozhodly, že budou v projektu pokraèo- I. blok: 9.15–10.15 pøedsedající: a hesla i grafiku prý pøevzal z internetu. vat samy, a to v upravené verzi pod ná- Ondøej Matìjka. -

Enslige Asylbarn Og Historiens Tvetydighet1

Barn nr. 3-4 2007:41–58, ISSN 0800–1669 © 2007 Norsk senter for barneforskning Enslige asylbarn og historiens tvetydighet1 Ketil Eide Sammendrag Denne artikkelen aktualiserer hvilke samfunnsmessige og omsorgspolitiske dilemmaer som oppstår i det norske samfunnet når det ankommer barn som er uten sine foreldres nære om- sorg og beskyttelse – barn som har en annerledes kulturell og etnisk bakgrunn, og som er flyktninger fra samfunn preget av væpnede konflikter eller annen organisert vold. Artikkelen fokuserer på hvordan samfunnet har oppfattet disse barnas situasjon på ulike tidspunkt og under ulike historiske omstendigheter, og hvilken praksis som har blitt utøvet når det gjelder mottak og omsorg. Den aktuelle historiske perioden er fra 1938 og fram mot år 2000. Utval- get består av fire grupper av flyktningbarn som kom til Norge uten sine foreldre.2 Disse fire utvalgene er jødiske barn som ankom 1938–39, ungarske barn som kom i 1956, tibetanske barn som kom i 1964, og enslige mindreårige flyktninger med ulik etnisk bakgrunn som kom i perioden 1989–92.3 1 Denne artikkelen bygger på avhandlingen: Tvetydige barn. Om barnemigranter i et historisk komparativt perspektiv. Universitetet i Bergen/IMER (Eide 2005). 2 Datamaterialet består av historiske dokumenter og 34 intervjuer med representanter fra de fire utvalgene, i tillegg til 19 intervjuer av hjelpere og beslutningstakere. Intervjuene er fore- tatt i perioden 1999–2002. De ulike utvalgene er ikke kronologisk framstilt i denne artikke- len, og de er også ulikt vektlagt i framstillingen. Dette er bevisst gjort uti fra hvilken tematikk som artikkelen aktualiserer. For mer detaljer om de fire utvalgene og metodisk tilnærming vises til avhandling (Eide 2005). -

About Odd Nansen

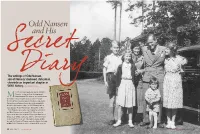

Odd Nansen and His The writings of Odd Nansen, June 1945: Odd nansen is reunited with his family son of Norway’s beloved statesman, after WWII. chronicle an important chapter in WWII history. By Timothy J. Boyce ost Norwegian-Americans know of Fridtjof Nansen—polar explorer, statesman and M humanitarian. His memory and achievements are widely celebrated in Norway, as attested by the October 2011 sesquicentennial celebration of his birth. But far fewer in America know about the remarkable y L life and achievements of his son, Odd Nansen, and in i M FA s particular his World War II diary, “From Day to Day.” ’ Odd Nansen, the fourth of five children of Fridtjof NANSEN and Eva Nansen, was born in 1901. He received a f ODD f O degree in architecture from the Norwegian Institute of esy rt u Technology (NTH), and from 1927 to 1930 lived and O PH c PH a worked in New York City. His father’s failing health R g brought Odd back to Norway, and after Fridtjof’s death PHOTO in May 1930 Nansen decided to remain. Following in 16 Viking May 2013 sonsofnorway.com sonsofnorway.com Viking May 2013 17 Nansen never intended to publish the diary, Fridtjof’s humanitarian secret diary, recording his From Day to Day Norwegians arrested during His entries also reveal but wrote it simply as a way to communicate with footsteps, Odd Nansen experiences, hopes, dreams The diary, later published the war, almost 7,500 were the quiet strength, and his wife Kari, and as a means of sorting out his helped establish and fears. -

Tesis Doctoral Año 2016

TESIS DOCTORAL AÑO 2016 EL PREMIO NOBEL DE LA PAZ EN EL CONTEXTO DE LAS RELACIONES INTERNACIONALES 1901-2015 EUGENIO HERNÁNDEZ GARCÍA LICENCIADO EN DERECHO DOCTORADO UNIÓN EUROPEA DIRECTOR: JAVIER ALVARADO PLANAS I TABLA DE CONTENIDO Introducción. ...................................................................................................................... 1 Alfred Nobel: sus relaciones con la física, la química, LA fisiología o la medicina, la literatura y el pacifismo ...................................................................................................... 4 Alfred Nobel: la física y la química .................................................................................................. 6 Nobel y la medicina ........................................................................................................................ 6 Nobel y la literatura ........................................................................................................................ 7 Nobel y la paz .................................................................................................................................. 8 Nobel filántropo ............................................................................................................................. 9 Nobel y España ............................................................................................................................. 10 El testamento y algunas vicisitudes hacía los premios ................................................................ -

Creative Urban Milieus

Creative Urban Milieus Historical Perspectives on Culture, Economy, and the City von Giacomo Bottá, Chris Breward, Alexa Färber, David Gilbert, Simon Gunn, Martina Heßler, Marjetta Hietala, Thomas Höpel, Jan Gert Hospers, Habbo Knoch, Jan Andreas May, Birgit Metzger, Sandra Schürmann, Jill Steward, Jörn Weinhold, Clemens Zimmermann 1. Auflage Creative Urban Milieus – Bottá / Breward / Färber / et al. schnell und portofrei erhältlich bei beck-shop.de DIE FACHBUCHHANDLUNG campus Frankfurt am Main 2008 Verlag C.H. Beck im Internet: www.beck.de ISBN 978 3 593 38547 1 Inhaltsverzeichnis: Creative Urban Milieus – Bottá / Breward / Färber / et al. »HOW M ANCHESTER IS A MUSED« 103 formative period between 1860 and 1900, in the conclusion I shall attempt to follow through trends over a longer period to gauge change and persis- tence in the cultural economy over time. The Origins of the Cultural Economy As we have just observed, prior to the mid-nineteenth century Manchester was not noted for its cultural life. Even W. Cooke Taylor, generally taken to be an apologist both for Manchester and the factory system, reported in 1842: »It is essentially a place of business, where pleasure is unknown as a pursuit, and amusements scarcely rank as secondary considerations« (Cooke Taylor 1842: 10). In this regard Manchester was little different from other towns and cities outside London, where polite culture ranked relatively low in the order of priorities behind business, often being con- fined to particular groups (the gentry, urban notables) and times of year (festivals, the »season«) (Borsay 1999; Money 1977). At Taylor’s time of writing there existed nevertheless an established network of institutions and associations of polite culture in Manchester. -

Journal September 1988

The Elgar Society JOURNAL SEPTEMBER •i 1988 .1 Contents Page Editorial 3 Articles: Elgar and Fritz Volbach 4 -i Hereford Church Street Plan Rejected 11 Elgar on Radio 3,1987 12 Annual General Meeting Report and Malvern Weekend 13 News Items 16 Concert Diary 20 Two Elgar Programmes (illustrations) 18/19 Record Review and CD Round-Up 21 News from the Branches 23 Letters 26 Subscriptions Back cover The editor does not necessarily agree with the views expressed by contributors nor does the Elgar Society accept responsibility for such views. The cover portrait is reproduced by kind permission of RADIO TIMES ELGAR SOCIETY JOURNAL ISSN 0143-1269 2 /■ The Elgar Society Journal 104 CRESCENT ROAD, NEW BARNET, HERTS. EN4 9RJ 01-440 2651 EDITORIAL Vol. 5, no. 6 September 1988 The first weekend in June (sounds like a song-title!) was one of the most enjoyable for Society members for some years. At least it was greatly enjoyed by those who attended the various events. Structured round the AGM in Great Malvern, the committee were the first to benefit from the hospitality of Lawnside. We met in the Library, passing first the awful warning “No hockey sticks or tennis racquets upstairs” (and we didn’t take any), and we were charmingly escorted round the somewhat confusing grounds and corridors by some of the girls of the school. After a lunch in the drawing room where the famous grand piano on which Elgar & GBS played duets at that first Malvern Festival so long ago, was duly admired (and played on), we went to the main school buildings for the AGM. -

Boroughreeves Records

Manchester Central Library Guide to Local Government Records m52110 Chorlton-on-Medlock Town Hall 1833 www.images.manchester.gov.uk The aim of this guide is to provide an introduction to the records held at Manchester Central Library for Manchester City Council and its predecessors and for the Greater Manchester Council. It also gives references to published material held in the library The town of Manchester was granted a charter in 1301 but lost borough status by a court case in 1359. Until the nineteenth century government was largely by manorial courts. In 1792 police commissioners were also established for the improvement of the area of the township of Manchester. In 1838 the Borough of Manchester was established, comprising the areas of Manchester, Beswick, Cheetham, Chorlton-upon-Medlock and Hulme townships. By 1846 the Borough Council had taken over the powers of the police commissioners. In 1853 the Borough received the title of City and between 1885 -1931 further areas were incorporated into the City of Manchester. In 1974 the City became a Metropolitan District in Greater Manchester County. Following the abolition of Greater Manchester County Council in 1986, Manchester City Council became a unitary authority. 1 For further information about the history of local government in Manchester please consult: Arthur Redford, The History of Local Government in Manchester, 3 volumes (Longmans Green, 1939-1940) (352.042 73 RE (325)). Shena Simon, A Century of City Government 1838-1938 (Allen and Unwin, 1938) The Manchester Muncipal Code, 6 volumes (Manchester Corporation, 1894-1901, 1928 supplement) (q352.042733Ma (181)). This is a digest of local acts of parliament etc. -

A History of the University of Manchester Since 1951

Pullan2004jkt 10/2/03 2:43 PM Page 1 University ofManchester A history ofthe HIS IS THE SECOND VOLUME of a history of the University of Manchester since 1951. It spans seventeen critical years in T which public funding was contracting, student grants were diminishing, instructions from the government and the University Grants Commission were multiplying, and universities feared for their reputation in the public eye. It provides a frank account of the University’s struggle against these difficulties and its efforts to prove the value of university education to society and the economy. This volume describes and analyses not only academic developments and changes in the structure and finances of the University, but the opinions and social and political lives of the staff and their students as well. It also examines the controversies of the 1970s and 1980s over such issues as feminism, free speech, ethical investment, academic freedom and the quest for efficient management. The author draws on official records, staff and student newspapers, and personal interviews with people who experienced the University in very 1973–90 different ways. With its wide range of academic interests and large student population, the University of Manchester was the biggest unitary university in the country, and its history illustrates the problems faced by almost all British universities. The book will appeal to past and present staff of the University and its alumni, and to anyone interested in the debates surrounding higher with MicheleAbendstern Brian Pullan education in the late twentieth century. A history of the University of Manchester 1951–73 by Brian Pullan with Michele Abendstern is also available from Manchester University Press. -

List Landscapes Designed by R. A. Hillier

A systematic list of butterflies seen in Norfolk. 15th March to 18th October 2009 (Version 3) SPECKLED WOOD LARGE HEATH SMALL TORTOISESHELL LARGE WHITE SATYRIDAE SATYRIDAE NYMPHALIDAE PIERIDAE Pararge aegeria Coenonympha tullia Aglais urticae Pieris brassicae WALL SMALL PEARL- LARGE TORTOISESHELL SMALL WHITE SATYRIDAE BORDERED FRITILLARY NYMPHALIDAE PIERIDAE Pararge megera NYMPHALIDAE Nymphalis polychloros Pieris rapae Clossiana selene GATEKEEPER PEACOCK GREEN-VEINED WHITE SATYRIDAE UNIDENTIFIED NYMPHALIDAE PIERIDAE Maniola tithonus FRITILLARY Nymphalis io Pieris napi NYMPHALIDAE MEADOW BROWN COMMA SMALL SKIPPER SATYRIDAE RED ADMIRAL NYMPHALIDAE HESPERIIDAE Maniola jurtina NYMPHALIDAE Polygonia c-album Thymelicus sylvestris Vanessa atalanta SMALL HEATH COMMON BLUE SATYRIDAE PAINTED LADY LYCAENIDAE Coenonympha NYMPHALIDAE Polyommatus icarus pamphilus Vanessa cardui HOLLY BLUE LYCAENIDAE Celastrina argiolus R. A. HILLIER 07.11.09 Cantley to Buckenham (Norfolk). Sunday 11th April 2010 Cloudy, cool, sunny (Version 2) R. A. HILLIER 19.04.10 Cantley to Buckenham (Norfolk). Sunday 11th April 2010 Cloudy, cool, sunny (Version 1) R. A. HILLIER 19.04.10 Cantley to Buckenham (Norfolk). Sunday 11th April 2010 Cloudy, cool, sunny (Version 3) R. A. HILLIER 21.08.10 A systematic list of birds seen in Norfolk. 2009 GREAT CRESTED GREBE SHOVELER COOT HERRING GULL SWALLOW SEDGE WARBLER ROOK (Podiceps cristatus) (Anas clypeata) Fulica atra) (Larus argentatus) (Hirundo rustica) (Acrocephalus (Corvus frugilegus) schoenobaenus) CORMORANT POCHARD COMMON CRANE