Joint Barents Transport Plan Proposals for Development of Transport Corridors for Further Studies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

VINNOVA and Its Role in the Swedish Innovation System - Accomplishments Since the Start in 2001 and Ambitions Forward

VINNOVA and its role in the Swedish Innovation System - Accomplishments since the start in 2001 and ambitions forward Per Eriksson, Director General VINNOVA (Swedish Governmental Agency for Innovation Systems) September 2006 VINNOVA and its role in the Swedish Innovation System • Some basic facts about VINNOVA • Critical steps in the Evolution of VINNOVA’s portfolio of programs • Some challenges ahead For reference: Some additional facts about the Swedish Research and Innovation System R&D expenditure in relation to GDP 2003 Israel Sweden Finland Japan Korea United States Universities & colleges Germany Government organisations Denmark Business sector Belgium France Canada Netherlands United Kingdom Norway Czech Republic 0,0 0,5 1,0 1,5 2,0 2,5 3,0 3,5 4,0 4,5 5,0 Per cent of GDP Source: OECD MSTI, 2005 Governmental financing of R&D in 2005 and 2006 in percent of GDP Per cent of GDP 1,2 Defence R&D Research foundations 1 Civil R&D 0,8 0,6 0,4 0,2 0 Sweden 2005 Finland 2005 Sweden 2006 Finland 2006 Källa: SCB 2005; OECD MSTI 2005 Swedish National Innovation System Characteristics: • The economy strongly internationally linked • The big international companies dominates the R&D-system • SME invest very little in R&D • Universities dominates the public R&D-system and they have a third task, to cooperate with companies and society • Small sector of Research-institutes • Government invests very little R&D-money in companies outside the military sector Major public R&D-funding organizations in Sweden and their budgets 2006 Ministry of Ministry -

Possible Solutions for Zero Emission Railways. Case Study

Possible Solutions For Zero Emission Railways MOZEES Workshop - 22nd – 23rd October: CIENS, Oslo – Forum Dag Aarsland, Senior Advisor Possible Solutions for Zero Emission Railways MANDAT Forprosjekt NULLFIB- NULLutslippsløsninger For Ikke-elektrifiserte Baner Non-electrified lines • 1395 km (approx. 1/3rd) of total 4150 km is non- electrified. • Estimated cost for electrification for Nordlandsbanen would be = 1- 1,3 Billion €. Other lines (Meråker line and Trondheim- Stjørdal) will be electrified. • Diesel consumption for all lines per year is approx. 16 mill/litre • Fuel consumption for a Cargo-train for example, Trondheim-Bodø is approx. 8000 litres (roundtrip). Freight train passing mountain Saltfjellet on the Nordland line. Considering four alternatives Transition from fossil-based to zero-carbon for passenger-trains, freight-trains and on-track- machines. Study of: • Hydrogen • Biogas • Biodiesel • Battery Deadline for the feasibility study is end of 2019. Bodø, terminus of the Nordland line Hydrogen operation – assessment by the end of 2019 • The Norwegian Government Transport Committee has requested the Railway Directorate to investigate the possibility of a test project with hydrogen operation of railway vehicles. • The directorate shall before end of 2019 assess the cost and feasibility of a pilot project. Alstom hydrogen powered train Feasibility study of battery operation • Feasibility study of battery-operation for Nordlandsbanen (Trondheim – Bodø). • Length 728km, 162 tunnels, 256 bridges, challenging operation conditions. • Including the line from Rana mines to Mo I Rana. Snow clearing on tracks on the mountain Saltfjellet on the Nordland line Contributors Electrification Is it possible in a cost-effective way only to electrify sections of the line? Horisontal profile – Nordland line What do the train manufacturers think? Consepts for passenger train with locomotive and coaches. -

Annual Report | 2018

Annual Report | 2018 A word from the CEO | This is Norconsult | Strategy 2019–2021 | Heads for tomorrow | Selected projects 2018 | Our market areas | Board of Directors’ Report for 2018 | Consolidated financial statements 5 326 Turnover (NOK, millions) Contents 6 000 5 000 4 000 3 000 2 000 A word from the CEO . 4 1 000 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 This is Norconsult Our business . 7 Corporate governance . 10 402 Strategy 2019–2021 . 12 Operating profit (NOK, millions) Heads for tomorrow #headsforrecruitment . 16 400 #headsforcareer . 18 #headsforsustainability . 21 300 #headsforresponsibility . 22 #headsforenvironment . 25 200 The little big differences 100 Selected projects 2018 . 28 Our market areas . 38 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 Board of Directors’ Report for 2018 . 46 Consolidated financial statements . 62 3 800 Forretningsidé Employees 2018 3 800 2017 3 200 2016 3 050 2015 2 970 2014 2 900 Front page photos Photo 1: Havøygavlen Wind Power Plant . Photo 2: City Bridge in Flekkefjord . Photo: Southern Region of the Norwegian Public Roads Administration 2 Photo 3: Norconsult’s employees working at the VEAS facility . Photo: Johnny Syversen 3 A word from the CEO | This is Norconsult | Strategy 2019–2021 | Heads for tomorrow | Selected projects 2018 | Our market areas | Board of Directors’ Report for 2018 | Consolidated financial statements As “Norconsultants”, everything we do must contribute to little big differences A word from the CEO that create added value for our clients. Photo: Erik Burås 2018 was a hectic and good year for the acquisition of Arkitekthuset joint Ringerike Railway Line and E16 In addition, we have been selected as main topics for the 2019–2021 strategy must sharpen our ability to be in the Norconsult . -

(CEF) 2019 TRANSPORT MAP CALL Proposal for the Selection of Projects

Connecting Europe Facility (CEF) 2019 TRANSPORT MAP CALL Proposal for the selection of projects July 2020 Innovation and Networks Executive Agency THE PROJECT DESCRIPTIONS IN THIS PUBLICATION ARE AS SUPPLIED BY APPLICANTS IN THE TENTEC PROPOSAL SUBMIS- SION SYSTEM. THE INNOVATION AND NETWORKS EXECUTIVE AGENCY CANNOT BE HELD RESPONSIBLE FOR ANY ISSUE ARISING FROM SAID DESCRIPTIONS. The Innovation and Networks Executive Agency is not liable for any consequence from the reuse of this publication. Brussels, Innovation and Networks Executive Agency (INEA), 2020 © European Union, 2020 Reuse is authorised provided the source is acknowledged. Distorting the original meaning or message of this document is not allowed. The reuse policy of European Commission documents is regulated by Decision 2011/833/EU (OJ L 330, 14.12.2011, p. 39). For any use or reproduction of photos and other material that is not under the copyright of the European Union, permission must be sought directly from the copyright holders. PDF ISBN 978-92-9208-086-0 doi:10.2840/16208 EF-02-20-472-EN-N Page 2 / 168 Table of Contents Commonly used abbreviations ......................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 7 Introduction ................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................ -

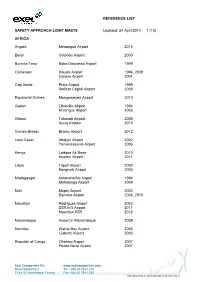

Reference List Safety Approach Light Masts

REFERENCE LIST SAFETY APPROACH LIGHT MASTS Updated: 24 April 2014 1 (10) AFRICA Angola Menongue Airport 2013 Benin Cotonou Airport 2000 Burkina Faso Bobo Diaulasso Airport 1999 Cameroon Douala Airport 1994, 2009 Garoua Airport 2001 Cap Verde Praia Airport 1999 Amilcar Capral Airport 2008 Equatorial Guinea Mongomeyen Airport 2010 Gabon Libreville Airport 1994 M’vengue Airport 2003 Ghana Takoradi Airport 2008 Accra Kotoka 2013 Guinea-Bissau Bissau Airport 2012 Ivory Coast Abidjan Airport 2002 Yamoussoukro Airport 2006 Kenya Laikipia Air Base 2010 Kisumu Airport 2011 Libya Tripoli Airport 2002 Benghazi Airport 2005 Madagasgar Antananarivo Airport 1994 Mahajanga Airport 2009 Mali Moptu Airport 2002 Bamako Airport 2004, 2010 Mauritius Rodrigues Airport 2002 SSR Int’l Airport 2011 Mauritius SSR 2012 Mozambique Airport in Mozambique 2008 Namibia Walvis Bay Airport 2005 Lüderitz Airport 2005 Republic of Congo Ollombo Airport 2007 Pointe Noire Airport 2007 Exel Composites Plc www.exelcomposites.com Muovilaaksontie 2 Tel. +358 20 754 1200 FI-82110 Heinävaara, Finland Fax +358 20 754 1330 This information is confidential unless otherwise stated REFERENCE LIST SAFETY APPROACH LIGHT MASTS Updated: 24 April 2014 2 (10) Brazzaville Airport 2008, 2010, 2013 Rwanda Kigali-Kamombe International Airport 2004 South Africa Kruger Mpumalanga Airport 2002 King Shaka Airport, Durban 2009 Lanseria Int’l Airport 2013 St. Helena Airport 2013 Sudan Merowe Airport 2007 Tansania Dar Es Salaam Airport 2009 Tunisia Tunis–Carthage International Airport 2011 ASIA China -

Lappstaden in Arvidsjaur Church Town Is Unique Portion of the Forested Areas in the Interior of – Nowhere Else Are There So Many Well-Preserved Upper Norrland

FOREST SAAMI UNIQUE The forest Saami in the past inhabited a large Lappstaden in Arvidsjaur church town is unique portion of the forested areas in the interior of – nowhere else are there so many well-preserved · 2013 TC G Upper Norrland. Today their territory is limited forest Saami gåhties (Saami pyramid-shaped G: INTIN R to the inland area between Vittangi in Norr- dwelling) as here. Their form combines that of the P YRÅ. YRÅ. botten County down to Malå in Västerbotten round gåhtie tent with the square timber dwelling. B PRÅK S X County with Arvidsjaur as the core area. The Lappstaden has never been used for permanent LE : E : N life of the forest Saami is adapted to that of living; only for overnight stays during church festi- O the forest reindeer, which finds all its forage vals. anslati . TR . N in forest areas and never needs to move to O mati the mountains. Before the 18th century, forest A POSITIVE ATMOSPHERE OR INF reindeer husbandry was small-scale, every The buildings in Lappstaden are owned by the R ultu household keeping about 10 domesticated re- forest Saami themselves and are still in use. Here, K MUNIN indeer. Hunting, and above all fishing, brought & people stay to spend time IN G HU the staple nutrition. together and the tradition :: N G DESI survives of spending the HIC P THE GREAT CHANGE night in Lappstaden A th th KIRUNA During the 18 and 19 centuries, conditions during the church & GR AND T X changed. The forestlands were populated by E feast, the last week- T non-nomadic settlers, who were allotted land end in August. -

Sami in Finland and Sweden

A baseline study of socio-economic effects of Northland Resources ore establishment in northern Sweden and Finland Indigenous peoples and rights Stefan Ekenberg Luleå University of Technology Department of Human Work Sciences 2008 Universitetstryckeriet, Luleå A baseline study of socio-economic effects of Northland Resources ore establishment in northern Sweden and Finland Indigenous peoples and rights Stefan Ekenberg Department of Human Work Sciences Luleå University of Technology 1 Summary The Sami is considered to be one people with a common homeland, Sápmi, but divided into four national states, Finland, Norway, Russia and Sweden. The indigenous rights therefore differ in each country. Finlands Sami policy may be described as accommodative. The accommodative Sami policy has had two consequences. Firstly, it has made Sami collective issues non-political and has thus change focus from previously political mobilization to present substate administration. Secondly, the depoliticization of the Finnish Sami probably can explain the absent of overt territorial conflicts. However, this has slightly changes due the discussions on implementation of the ILO Convention No 169. Swedish Sami politics can be described by quarrel and distrust. Recently the implementation of ILO Convention No 169 has changed this description slightly and now there is a clear legal demand to consult the Sami in land use issues that may affect the Sami. The Reindeer herding is an important indigenous symbol and business for the Sami especially for the Swedish Sami. Here is the reindeer herding organized in a so called Sameby, which is an economic organisations responsible for the reindeer herding. Only Sami that have parents or grandparents who was a member of a Sameby may become members. -

View Its System of Classification of European Rail Gauges in the Light of Such Developments

ReportReport onon thethe CurrentCurrent StateState ofof CombinedCombined TransportTransport inin EuropeEurope EUROPEAN CONFERENCE OF MINISTERS TRANSPORT EUROPEAN CONFERENCE OF MINISTERS OF TRANSPORT REPORT ON THE CURRENT STATE OF COMBINED TRANSPORT IN EUROPE EUROPEAN CONFERENCE OF MINISTERS OF TRANSPORT (ECMT) The European Conference of Ministers of Transport (ECMT) is an inter-governmental organisation established by a Protocol signed in Brussels on 17 October 1953. It is a forum in which Ministers responsible for transport, and more speci®cally the inland transport sector, can co-operate on policy. Within this forum, Ministers can openly discuss current problems and agree upon joint approaches aimed at improving the utilisation and at ensuring the rational development of European transport systems of international importance. At present, the ECMT's role primarily consists of: ± helping to create an integrated transport system throughout the enlarged Europe that is economically and technically ef®cient, meets the highest possible safety and environmental standards and takes full account of the social dimension; ± helping also to build a bridge between the European Union and the rest of the continent at a political level. The Council of the Conference comprises the Ministers of Transport of 39 full Member countries: Albania, Austria, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Belgium, Bosnia-Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Croatia, the Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, the Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia (F.Y.R.O.M.), Georgia, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Iceland, Ireland, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Moldova, Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Romania, the Russian Federation, the Slovak Republic, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Turkey, Ukraine and the United Kingdom. There are ®ve Associate member countries (Australia, Canada, Japan, New Zealand and the United States) and three Observer countries (Armenia, Liechtenstein and Morocco). -

Railway Power Supply System Models for Static Calculations in a Modular Design Implementation

Railway power supply system models for static calculations in a modular design implementation Usability illustrated by case-studies of northern Malmbanan RONNY SKOGBERG Master’s Degree Project Stockholm, Sweden 2013 XR-EE-ES 2013:006 Railway power supply system models for static calculations in a modular design implementation Usability illustrated by case-studies of northern Malmbanan RONNY SKOGBERG Master of Science Thesis Royal Institute of Technology School of Electrical Engineering Electric Power Systems Stockholm, Sweden, 2013 Supervisors: Lars Abrahamsson, KTH Mario Lagos, Transrail AB Examiner: Lennart Söder XR-EE-ES 2013:006 Abstract Several previous theses and reports have shown that voltage variations, and other types of supply changes, can influence the performance and movements of trains. As part of a modular software package for railway focused calculations, the need to take into account for the electrical behavior of the system was needed, to be used for both planning and operational uses. In this thesis, different static models are presented and used for train related power flow calculations. A previous model used for converter stations is also extended to handle different configurations of multiple converters. A special interest in the train type IORE, which is used for iron ore transports along Malmbanan, and the power systems influence to its performance, as available modules, for mechanical calculations, in the software uses the same train type. A part of this project was to examine changes in the power systems performance if the control of the train converters were changed, both during motoring and regenerative braking. A proposed node model, for the static parts of a railway power system, has been used to simplify the building of the power system model and implementation of the simulation environment. -

Representing the SPANISH RAILWAY INDUSTRY

Mafex corporate magazine Spanish Railway Association Issue 20. September 2019 MAFEX Anniversary years representing the SPANISH RAILWAY INDUSTRY SPECIAL INNOVATION DESTINATION Special feature on the Mafex 7th Mafex will spearhead the European Nordic countries invest in railway International Railway Convention. Project entitled H2020 RailActivation. innovation. IN DEPT MAFEX ◗ Table of Contents MAFEX 15TH ANNIVERSARY / EDITORIAL Mafex reaches 15 years of intense 05 activity as a benchmark association for an innovative, cutting-edge industry 06 / MAFEX INFORMS with an increasingly marked presence ANNUAL PARTNERS’ MEETING: throughout the world. MAFEX EXPANDS THE NUMBER OF ASSOCIATES AND BOLSTERS ITS BALANCE APPRAISAL OF THE 7TH ACTIVITIES FOR 2019 INTERNATIONAL RAILWAY CONVENTION The Association informed the Annual Once again, the industry welcomed this Partners’ Meeting of the progress made biennial event in a very positive manner in the previous year, the incorporation which brought together delegates from 30 of new companies and the evolution of countries and more than 120 senior official activities for the 2019-2020 timeframe. from Spanish companies and bodies. MEMBERS NEWS MAFEX UNVEILS THE 26 / RAILACTIVACTION PROJECT The RailActivation project was unveiled at the Kick-Off Meeting of the 38 / DESTINATION European Commission. SCANDINAVIAN COUNTRIES Denmark, Norway and Sweden have MAFEX PARTICIPTES IN THE investment plans underway to modernise ENTREPRENEURIAL ENCOUNTER the railway network and digitise services. With the Minister of Infrastructure The three countries advance towards an Development of the United Arab innovative transport model. Emirates, Abdullah Belhaif Alnuami held in the office of CEOE. 61 / INTERVIEW Jan Schneider-Tilli, AGREEMENT BETWEEN BCIE AND Programme Director of Banedanmark. MAFEX To promote and support internationalisation in the Spanish railway sector. -

How People Regard the Mine Establishment in Kaunisvaara, Tapuli and Hannukainen Areas

A baseline study of socio-economic effects of Northland Resources ore establishment in northern Sweden and Finland How people regard the mine establishment in Kaunisvaara, Tapuli and Hannukainen areas Peter Waara, Leif Berglund, Leena Soudunsaari and Ville Koskimäki Luleå University of Technology Department of Human Work Sciences 2008 Universitetstryckeriet, Luleå A baseline study of socio-economic effects of Northland Resources ore establishment in northern Sweden and Finland How people regard the mine establishment in Kaunisvaara, Tapuli and Hannukainen areas Peter Waara, Leif Berglund, Leena Soudunsaari and Ville Koskimäki Department of Human Work Sciences Luleå University of Technology 2 Summary of interview study. It is difficult to define who is or is not a legitimate stakeholder when it comes to issues that most likely will affect a community and a region for some 30 or 40 years. With regard taken to known sources of influence, such as environmental effects open pits eventually will give raise to, the dimensions of not yet acknowledged risks, effects and other factors will, sooner or later, be addressed in debates, thoughts and also actions of various kind. Who will be more or less likely to act and to react against the opening of mines in these remote areas in Finland and Sweden? Such questions will not be answered in this paper/report, since we have no possibility to foresee how people actually will respond to both positive as well as negative effects of the development of iron ore mining in Kaunisvaara and in Haanukainen. Our report aims to define and present on a descriptive level how a sample of people from both Finland and Sweden today, before the mines are opened, think about opportunities and risks associ- ated to the exploitation of iron ore in this region. -

Finnish Perspective on the TEN-T Core Network Corridors Extension

Finnish perspective on the TEN-T Core Network Corridors Extension Marko Mäenpää Finnish Transport and Communications Agency 26th February 2021 1 TEN-T CORE NETWORK EXTENSION IN FINLAND North Sea–Baltic Corridor from Helsinki to Tornio and further to Luleå Scandinavian– Mediterranean Corridor from Stockholm via Luleå to Narvik and Oulu. 2 TEN-T Core Network TEN-T CORE NETWORK IN FINLAND TEN-T Core Network Includes: Roads E18 Turku–Vaalimaa, Main roads 4 and 29 Helsinki–Tornio–border Track sections Turku–Helsinki–Lahti–Kouvola– Kotka/Vainikkala and Helsinki–Tampere–Oulu–Tornio– border Saimaa inland waterways Airports of Helsinki and Turku Ports of HaminaKotka, Helsingin, Turku and Naantali Kouvola RRT Urban nodes of Helsinki and Turku TEN-T Core Network Coverage: Core network road and railway network length is approx. 2 460 km Length of Saimaa area deep channel is approx. [Esityksen nimi] 780 km 3 The National Transport System Plan The first, comprehensive, long-term strategic plan for development of the transport system in Finland. The Plan will cover all transport modes, passenger and goods transport, transport networks, services and support measures for the transport system. The Plan is drawn up for a period of 12 years (2021–2032) and will be updated each Government term. The preparations are guided by a parliamentary steering group. The decision on the Plan will be made by the Government. According to the Plan, the TEN-T Corridors, reform of the TEN-T Guidelines and CEF funding are important and Finland wants to influence and utilise them. The emphasis is on railways. 4 Challenges on the railway network and TEN-T criteria The extension is very welcomed and The most critical renovation needs The most challenging rail sections creates new possibilities to improve on railway network.