Interactive Documentary

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Plan Technologique 2016-2020

L’ONF EST UN PRODUCTEUR ET DISTRIBUTEUR PUBLIQUE D’OEUVRES AUDIOVISUELLES. • Établis en 1939. • Plus de 14,000 productions dont 200 en développement chaque année. • 13 studios dans 9 villes canadiennes. • Principalement des documentaires, animations et des œuvres interactives. • 75 nominations aux Oscar®, plus de 5,000 prix. Inventaire • Collection d’oeuvres - 14 000 linéaires ( 10 000 en format pellicule, 3000 en format vidéos et 1000 en format « Born Digital ») - 100 intéractives (web, application) •Plans d’archives 4000 heures ou 60 000 plans •Musique et effets sonores 20 0000 effets et 6000 rubans-maître de musique •Photos 500 000 éléments Plan de numérisation et conservation En 2008 l’ONF à démarrer la mise en oeuvre d’un vaste plan de numérisation et conservation. 1. Favoriser l’accessibilité actuelle et future des œuvres de l’ONF en formats numériques. 2. Assurer la préservation des Objectifs œuvres de l’ONF sur les supports numériques. 3. Restaurer les œuvres de l’ONF ayant subi des détériorations dues à l’usure. Plan de numérisation et conservation À date nous avons numérisé toutes les œuvres de la collection active (soit 60 % des oeuvres). Afin de répondre aux demandes d’accessibilité courantes de l’ONF Ainsi, nous traitons 8000 titres. Ils se répartissent ainsi : - 1500 titres en 35 mm - 4500 titres en 16 mm - 1500 titres en vidéo (SD ou HD) - 500 titres « Born Digital » Nous numérisons nos œuvres sur film dans les résolutions suivantes : - 3K - les œuvres en bon état en format 16 mm ou en 35 mm - 6K - les œuvres patrimoniales en 16 mm et en 35 mm, les œuvres à risque en 16 et 35 mm Les œuvres en format vidéo (SD et HD) et Born Digital dans la meilleure résolution offerte par la source. -

NFB TEAM Producer Mixing Hugues Sweeney Serge Boivin Geoffrey Mitchell Administrator Jean-Paul Vialard Manon Provencher Luc Léger

nfb.ca/mytribe An interActive documentAry thAt Allows us to experience the worlds of 8 music fAns And see how the internet trAnsforms their interpersonAl relAtionships And helps forge their identity. 8 chArActers, 8 music styles, 8 views of the web And sociAl networks. PRESS KIT An interActive documentAry thAt Allows us to experience the worlds of 8 music fAns And see how the internet trAnsforms their interpersonAl relAtionships And helps forge their identity. 8 chArActers, 8 music styles, 8 views of the web And sociAl networks. nfb.ca/mytribe from reallife? is it a powerful conversely, engine for the distinctions construction or, of new communities? Can the virtual even be dissociated apprehend the world’s diversity if they are systematically searching for what is But “the can same?” Does the the reassurance Internet offered erase cultural by this virtual social life result in isolation, even to the exclusion of reality? “safe virtual home”,aspaceinwhichtoopenupandrevealone’strueself. How do users a becomes thus Web The validated. been has identity their that proof opinions—all and approval, of signs comments, receive to for their “fellows,” they choose a tribe to which to belong. In return for expressing themselves, sharing and posting, they expect Online social networks enable people to images share and music, emotions. information, Looking vehicle for forging an identity. each To his own “tribe”: Goth, emo, reggae, rap, vampire … Music is often more than a simple cultural product; it acts as a born between1982and1996.Thispermanentconnectionnecessarilychangeshowtheyseetheworld. users “connected”)—Web (for “C” Generation is This online. week a hours twenty than more spending are Quebecers young went, goes virtual, the definition remains unchanged but the practice revolutionizesTwenty everyday years after life. -

2012–2013 NFB Annual Report

Annual Report T R L REPO A NNU 20 1 2 A 201 3 TABLE 03 Governance OF CONTENTS 04 Management 01 Message from 05 Summary of the NFB Activities 02 Awards Received 06 Financial Statements Annex I NFB Across Canada Annex II Productions Annex III Independent Film Projects Supported by ACIC and FAP Photos from French Program productions are featured in the French-language version of this annual report at http://onf-nfb.gc.ca/rapports-annuels. © 2013 National Film Board of Canada ©Published 2013 National by: Film Board of Canada Corporate Communications PublishedP.O. Box 6100,by: Station Centre-ville CorporateMontreal, CommunicationsQuebec H3C 3H5 P.O. Box 6100, Station Centre-ville Montreal,Phone:© 2012 514-283-2469 NationalQuebec H3CFilm Board3H5 of Canada Fax: 514-496-4372 Phone:Internet:Published 514-283-2469 onf-nfb.gc.ca by: Fax:Corporate 514-496-4372 Communications Internet:ISBN:P.O. Box 0-7722-1272-4 onf-nfb.gc.ca 6100, Station Centre-ville Montreal, Quebec H3C 3H5 4th quarter 2013 ISBN: 0-7722-1272-4 4thPhone: quarter 514-283-2469 2013 GraphicFax: 514-496-4372 design: Oblik Communication-design GraphicInternet: design: ONF-NFB.gc.ca Oblik Communication-design ISBN: 0-7722-1271-6 4th quarter 2012 Cover: Stories We Tell, Sarah Polley Graphic design: Folio et Garetti Cover: Stories We Tell, Sarah Polley Cover: Soldier Brother Printed in Canada/100% recycled paper Printed in Canada/100% recycled paper Printed in Canada/100% recycled paper 2012–2013 NFB Annual Report 2012–2013 93 Independent film projects IN NUMBERS supported by the NFB (FAP and ACIC) 76 Original NFB films and 135 co-productions Awards 8 491 New productions on Interactive websites NFB.ca/ONF.ca 83 33,721 Digital documents supporting DVD units (and other products) interactive works sold in Canada * 7,957 2 Public installations Public and private screenings at the NFB mediatheques (Montreal and Toronto) and other community screenings 3 Applications for tablets 6,126 Television broadcasts in Canada * The NFB mediatheques were closed on September 1, 2012, and the public screening program was expanded. -

Webdocumentário E As Funções Para a Interação No Gênero Emergente: Análise De Fort Mcmoney E Bear 71

PONTIFÍCIA UNIVERSIDADE CATÓLICA DO RIO GRANDE DO SUL ― PUCRS UNIDADE ACADÊMICA DE PESQUISA E PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM COMUNICAÇÃO SOCIAL FERNANDA BERNARDES WEBDOCUMENTÁRIO E AS FUNÇÕES PARA A INTERAÇÃO NO GÊNERO EMERGENTE: ANÁLISE DE FORT MCMONEY E BEAR 71 Porto Alegre 2015 Fernanda Bernardes WEBDOCUMENTÁRIO E AS FUNÇÕES PARA A INTERAÇÃO NO GÊNERO EMERGENTE: Análise de Fort Mcmoney e Bear 71 Dissertação apresentada como requisito para obtenção do título de Mestre pelo Programa de Pós- Graduação em Comunicação Social da Faculdade de Comunicação da Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Rio Grande do Sul ― PUCRS. Orientador: Roberto Tietzmann. Porto Alegre 2015 Fernanda Bernardes WEBDOCUMENTÁRIO E AS FUNÇÕES PARA A INTERAÇÃO NO GÊNERO EMERGENTE: Análise de Fort Mcmoney e Bear 71 Dissertação apresentada como requisito para obtenção do título de Mestre pelo Programa de Pós- Graduação em Comunicação Social da Faculdade de Comunicação da Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Rio Grande do Sul ― PUCRS. Aprovada em ___ de ____________ de ____. BANCA EXAMINADORA Orientador: Prof. Dr. Roberto Tietzmann – PUCRS Prof. Dr. André Fagundes Pase – PUCRS Prof.ª Dr.ª Miriam de Souza Rossini – UFRGS LISTA DE IMAGENS Figura 1. Proposta de leitura dos gêneros documentário interativo e webdocumentário ......... 19 Figura 2. Navegação em Aspen Movie Map ............................................................................. 28 Figura 3. Cena de Moss Landing ............................................................................................. -

Interactive Project Proposals: the Early Stages

Working With the NFB’s Digital Studio June 2015 Working With the NFB’s Digital Studio As a unique creative and cultural laboratory, The NFB is eager to explore what it means to “create” and “connect” with Canadians in the age of technology. We are looking to work with a wide range of Canadian artists and media-makers interested in experimenting with the creative application of platforms and technology to story and form. Filmmakers, Interactive Designers, Photographers, Social Media Producers, Graphic Artists, Information Architects, Writers, Video and Sound Artists, Musicians, etc. We are excited by the collaborative nature of media today and are open to receiving project proposals from all types of artists and creators. What Kinds of Creations? As a public producer we have a duty to contribute to the ongoing social discourse of the day through the production of creative audiovisual works. We remain convinced of the powerful and transformative effects of art and imagination for the public good. We have a strong code of ethics that guides our work including the importance of an artistic voice and a diversity of voices, authenticity and creative excellence, innovation and risk taking, social relevance and the promotion of a civic, inclusive democratic culture. Our approach to story is innovative, open-ended, and participatory. We strive to create groundbreaking works that harness the appropriate technologies for each story and/or audience group, and contain built-in channels that open the project up for direct engagement. We are currently looking to produce new works that help us achieve our mission including interactive documentaries, mobile and locative media, interactive animations, photographic art and essays, data visualizations, physical installations, community media, interactive video, user- generated media, etc. -

VERSÃO INTEGRAL (Pdf)

#18 INTERATIVIDADE E DOCUMENTÁRIO INTERACTIVIDAD Y DOCUMENTAL INTERACTIVITY AND DOCUMENTARY INTERACTIVITÉ ET DOCUMENTAIRE SETEMBRO/2015 CONSELHO EDITORIAL Alfonso Palazón (Universidad Rey Juan Carlos, Espanha) Annie Comolli (École Pratique des Hautes Études, França) António Fidalgo (Universidade da Beira Interior, Portugal) António Weinrichter (Universidad Carlos III, Espanha) Bienvenido León Anguiano (Universidad de Navarra, Espanha) Casimiro Torreiro (Universidad Carlos III Madrid, Espanha) Cássio dos Santos Tomaim (Universidade Federal de Santa Maria, Brasil) Catherine Benamou (Universidade da California-Irvine, EUA) Claudine de France (Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique - CNRS, França) Frederico Lopes (Universidade da Beira Interior, Portugal) Gordon D. Henry (Michigan State University, EUA) Javier Campo (Universidad Nacional del Centro - UNICEN; Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas - CONICET, Argentina) José da Silva Ribeiro (Universidade Aberta, Portugal) José Filipe Costa (IADE-Instituto de Artes Visuais, Design e Marketing, Portugal) João Luiz Vieira (Universidade Federal Fluminense, Brasil) Julio Montero (Universidad Complutense de Madrid, Espanha) Luís Nogueira (Universidade da Beira Interior, Portugal) Luiz Antonio Coelho (Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Rio de Janeiro, Brasil) Margarita Ledo Andión (Universidad de Santiago de Compostela, Espanha) María Luisa Ortega Gálvez (Universidad Autónoma de Madrid, España) Michel Marie (Université de la Sorbonne Nouvelle - Paris III , França) Miguel -

No Classes, University Open) Oct

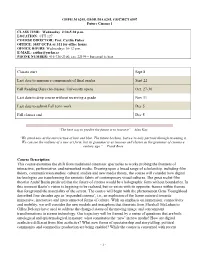

GS/FILM 6245, GS/HUMA 6245, GS/CMCT 6507 Future Cinema 1 CLASS TIME: Wednesday 2:30-5:30 p.m. LOCATION: CFT 127 COURSE DIRECTOR: Prof. Caitlin Fisher OFFICE: 303F GCFA or 311 for office hours OFFICE HOURS: Wednesdays 10-12 p.m. E-MAIL: [email protected] PHONE NUMBER: 416-736-2100, ext. 22199 – but email is best Classes start Sept 8 Last date to announce components of final grades Sept 22 Fall Reading Days (no classes, University open) Oct. 27-30 Last date to drop course without receiving a grade Nov 11 Last date to submit Fall term work Dec 5 Fall classes end Dec 5 “The best way to predict the future is to invent it” – Alan Kay “We stand now at the intersection of lure and blur. The future beckons, but we’re only partway through inventing it. We can see the outlines of a new art form, but its grammar is as tenuous and elusive as the grammar of cinema a century ago.” – Frank Rose Course Description This course examines the shift from traditional cinematic spectacles to works probing the frontiers of interactive, performative, and networked media. Drawing upon a broad range of scholarship, including film theory, communication studies, cultural studies and new media theory, the course will consider how digital technologies are transforming the semiotic fabric of contemporary visual cultures. The great realist film theorist André Bazin predicted that the future of cinema would be a holographic form without boundaries. In this moment Bazin’s vision is begining to be realized, but co-exists with its opposite: frames within frames that foreground the materiality of the screen. -

Nfb Interactive Onf Interactif

NFB INTERACTIVE CONTACTS ONF NATHALIE LOUIS-CHARLES TAMMY BOURDON MIGNOT-GRENIER PEDDLE INTERACTIF DIRECTOR, DISTRIBUTION AGENT, SALES & MARKET MARKETING MANAGER & MARKET DEVELOPMENT / DEVELOPMENT / AGENT, NFB INTERACTIVE/ DIRECTRICE, DISTRIBUTION & VENTES & DÉVELOPPEMENT AGENTE DE MISE EN MARCHÉ DÉVELOPPEMENT DE MARCHÉ DE MARCHÉ ONF INTERACTIF +1-514-995-0095 +1-514-242-6264 +1-514-996-7776 VIRTUAL REALITY/ [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] RÉALITÉ VIRTUELLE NFB.CA | ONF.CA © 2019 National Film Board of Canada. Printed in Canada. | Office national du film du Canada. Imprimé au Canada. G BLIND VAYSHA VR | VAYSHA L’AVEUGLE RV DREAM | RÊVE 8 MIN | 2017 | SAMSUNG GEAR | THEODORE USHEV | ENGLISH/FRENCH, ANGLAIS/FRANÇAIS 10 MIN | 2018 | OCULUS RIFT, WEB VR | PHILIPPE LAMBERT | ENGLISH/FRENCH, ANGLAIS/FRANÇAIS Vaysha is not like other girls: her left eye sees only the past, and her right eye only the future. Dream is an experience-generating system based on the unique mechanisms of dreams, “Blind Vaysha”—that’s what everyone calls her. Experience the immersive VR version of this which seem to draw on personal, collective and genetic memories. A creation by Philippe Lambert, visually stunning Oscar®-nominated short. Produced by the NFB. Based on the film nominated for Best with Édouard Lanctôt-Benoit, Vincent Lambert and Caroline Robert. Produced by the NFB. Animated Short Film 89th Academy Awards®. Rêve est un générateur d’expériences inspiré des mécanismes uniques des rêves qui demande que Vaysha n’est pas une fille comme les autres. Elle ne voit que le passé de l’œil gauche et le futur de l’œil nous reconsidérions notre relation avec le monde du rêve et le monde éveillé. -

Version Téléchargeable Comme Quatre Saisons Dans La Vie De Ludovic Et L’Univers De Co Hoedeman Ou Mclaren - L’Intégrale Offrent Des Modèles Intéressants »

Une visite guidée exceptionnelle sur Le Blog documentaire , avec une destination de choix ! Un havre de paix et de création, une pépinière de talents en devenir ou confirmés, un territoire où l'on se sent bien dès qu'on en pousse la porte. Bref, l'un des temples de la création (web)documentaire dans le monde... Plongée au cœur de l'Office National du Film du Canada , là où se pense et où se créé depuis 75 ans le présent et l'avenir des arts qui nous intéressent ici. © David Dufresne Si vous imaginiez l'ONF en plein centre de Montréal, juste à côté d'un parc dont cette ville a le secret, c'est raté - pour l'instant, tout du moins. Les locaux un peu austères sont situés au 3155, chemin de la Côte-de-Liesse, au bord d'une voie rapide en périphérie de la Métropole Québécoise... Un étrange no man's land qui abrite pourtant l'un des fleurons de la création documentaire (interactive). Pour se repérer dans ce dédale de couloirs aux allures d'hôpital ( « Il y a de toutes façons beaucoup de fous ici » , ironise Hugues Sweeney, producteur exécutif au studio interactif), un seul guide s'impose : Marie-Claude Lamoureux, qui est bien plus que la "relationniste médias" que présente sa carte de visite. Marie-Claude est une boule d'énergie à l'enthousiasme communicatif. Une québécoise alerte au verbe haut perché qui a l'audace du vinaigre sur les frites. Une boussole pour le visiteur, franche et sincère , avec qui il est très plaisant de refaire le monde (de la création) autour d'un café. -

Nfb Films and Photos at Montréal-Trudeau Airport Shine Spotlight on Montreal

NFB FILMS AND PHOTOS AT MONTRÉAL-TRUDEAU AIRPORT SHINE SPOTLIGHT ON MONTREAL Montreal, May 11, 2011 – What has brought two such very different Canadian institutions together? The desire to make Canadian art by local artists accessible to Canadians and visitors. Aéroports de Montréal (ADM) and the National Film Board of Canada (NFB) have joined forces to show NFB photographs, films and animated works at Montréal-Trudeau Airport under the Montréal Identity program, better known as L’Aérogalerie. Over the next year or so, three locations at the terminal will be the venue for selected works specially adapted for the occasion. The NFB’s French Program is also considering producing original works for Aéroports de Montréal. “Once again, the NFB is finding innovative ways to make its works accessible to as many people as possible. With this new partnership, the NFB and ADM are offering some 13 million visitors to the air terminal a unique cultural experience and a novel way of viewing Montreal and the work of great Canadian creators, whether expressed through conventional film techniques, animation or multimedia,” said Tom Perlmutter, Government Film Commissioner and Chairperson of the National Film Board of Canada. “The exhibition is part of the Montréal Identity program, also known as L’Aérogalerie, an initiative that we implemented in 2005 with the aim of infusing the airport facilities with a typically ‘Montreal’ character, as well as helping support the city’s artistic and cultural development. Our partnership with the NFB will enhance the program. I know our passengers will love these films and photographs,” said Christiane Beaulieu, ADM’s Vice President of Public Affairs and Communications. -

Future of Storytelling and Museum of the Moving Image Announce Immersive Media Exhibition 'Sensory Stories'

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE FUTURE OF STORYTELLING AND MUSEUM OF THE MOVING IMAGE ANNOUNCE IMMERSIVE MEDIA EXHIBITION ‘SENSORY STORIES’ Featuring seventeen virtual-reality and interactive works that engage sight, hearing, touch, and smell April 18–July 26, 2015 New York, New York, April 14, 2015—Museum of the Moving Image and the Future of StoryTelling present Sensory Stories, an exhibition that reveals how an emerging group of artists and companies are using innovative digital techniques to change the way audiences experience storytelling. The exhibition, which includes virtual-reality experiences, interactive films, participatory installations, and new touch responsive interfaces, opens on April 18, 2015, and will be on view through July 26, 2015, at the Museum. “Technology has driven the evolution of moving image entertainment since the invention of film,” said Carl Goodman, the Museum’s Executive Director. “Today, new technologies and interfaces aim to bring the body, mind, and senses into a new relationship with the moving image, one which eliminates the gap between the real and the virtual, the physical and the digital. We asked Future of Storytelling to develop an exhibition for the Museum because of their unique expertise in these important developments.” Conceived and organized by the Future of StoryTelling (FoST), Sensory Stories invites visitors to participate in narratives that merge traditional storytelling with groundbreaking new technologies, incorporating full-body immersion, and interaction that includes sight, hearing, touch, -

Rapport Annuel Annual Report

RAPPORT ANNUEL 2017-2018 2017-2018 RAPPORT ANNUEL DE L’ONF NFB ANNUAL REPORT 2017–2018 2017–2018 REPORT ANNUAL ANNUAL Published by: Strategic Planning and Government Relations P.O. Box 6100, Station Centre-ville Montreal, Quebec H3C 3H5 Internet: onf-nfb.gc.ca E-mail: [email protected] Cover page: THREE THOUSAND, Asinnajaq © 2018 National Film Board of Canada ISBN: 978-0-7722-1301-3 2nd Quarter 2018 Printed in Canada. TABLE OF CONTENTS 6 2017–2018 IN NUMBERS 9 MESSAGE FROM THE GOVERNMENT FILM COMMISSIONER 12 HIGHLIGHTS 13 THE NFB: A CENTRE FOR CREATIVITY AND EXCELLENCE 22 AN ORGANIZATION THAT REFLECTS THE RICHNESS AND DIVERSITY OF THE COUNTRY 27 WORKS THAT REACH LARGER AUDIENCES, RAISE QUESTIONS AND ENGAGE 32 AN ORGANIZATION THAT’S FOCUSED ON THE FUTURE 36 AWARDS AND HONOURS 47 GOVERNANCE 49 MANAGEMENT 50 SUMMARY OF ACTIVITIES 2017–2018 55 FINANCIAL STATEMENTS 74 ANNEX I: THE NFB ACROSS CANADA 77 ANNEX II: PRODUCTIONS 83 ANNEX III: INDEPENDANT FILM PROJECTS SUPPORTED BY ACIC AND FAP Return to the Table of Contents 1999 Samara Grace Chadwick Return to the Table of Contents August 20, 2018 The Honourable Pablo Rodriguez Minister of Canadian Heritage and Multiculturalism Ottawa, Ontario Minister: I have the honour of submitting to you, in accordance with the provisions of section 20(1) of the National Film Act, the Annual Report of the National Film Board of Canada for the period ended March 31, 2018. The report also provides highlights of noteworthy events of this fiscal year. Yours respectfully, Claude Joli-Coeur Government Film Commissioner