Resurgence of Harrisia Portoricensis (Cactaceae) on Desecheo Island After the Removal of Invasive Vertebrates: Management Implications

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Caryophyllales 2018 Instituto De Biología, UNAM September 17-23

Caryophyllales 2018 Instituto de Biología, UNAM September 17-23 LOCAL ORGANIZERS Hilda Flores-Olvera, Salvador Arias and Helga Ochoterena, IBUNAM ORGANIZING COMMITTEE Walter G. Berendsohn and Sabine von Mering, BGBM, Berlin, Germany Patricia Hernández-Ledesma, INECOL-Unidad Pátzcuaro, México Gilberto Ocampo, Universidad Autónoma de Aguascalientes, México Ivonne Sánchez del Pino, CICY, Centro de Investigación Científica de Yucatán, Mérida, Yucatán, México SCIENTIFIC COMMITTEE Thomas Borsch, BGBM, Germany Fernando O. Zuloaga, Instituto de Botánica Darwinion, Argentina Victor Sánchez Cordero, IBUNAM, México Cornelia Klak, Bolus Herbarium, Department of Biological Sciences, University of Cape Town, South Africa Hossein Akhani, Department of Plant Sciences, School of Biology, College of Science, University of Tehran, Iran Alexander P. Sukhorukov, Moscow State University, Russia Michael J. Moore, Oberlin College, USA Compilation: Helga Ochoterena / Graphic Design: Julio C. Montero, Diana Martínez GENERAL PROGRAM . 4 MONDAY Monday’s Program . 7 Monday’s Abstracts . 9 TUESDAY Tuesday ‘s Program . 16 Tuesday’s Abstracts . 19 WEDNESDAY Wednesday’s Program . 32 Wednesday’s Abstracs . 35 POSTERS Posters’ Abstracts . 47 WORKSHOPS Workshop 1 . 61 Workshop 2 . 62 PARTICIPANTS . 63 GENERAL INFORMATION . 66 4 Caryophyllales 2018 Caryophyllales General program Monday 17 Tuesday 18 Wednesday 19 Thursday 20 Friday 21 Saturday 22 Sunday 23 Workshop 1 Workshop 2 9:00-10:00 Key note talks Walter G. Michael J. Moore, Berendsohn, Sabine Ya Yang, Diego F. Registration -

In Search of the Extinct Hutia in Cave Deposits of Isla De Mona, P.R. by Ángel M

In Search of the Extinct Hutia in Cave Deposits of Isla de Mona, P.R. by Ángel M. Nieves-Rivera, M.S. and Donald A. McFarlane, Ph.D. Isolobodon portoricensis, the extinct have been domesticated, and its abundant (14C) date was obtained on charcoal and Puerto Rican hutia (a large guinea-pig like remains in kitchen middens indicate that it bone fragments from Cueva Negra, rodent), was about the size of the surviving formed part of the diet for the early settlers associated with hutia bones (Frank, 1998). Hispaniolan hutia Plagiodontia (Rodentia: (Nowak, 1991; Flemming and MacPhee, This analysis yielded an uncorrected 14C age Capromydae). Isolobodon portoricensis was 1999). This species of hutia was extinct, of 380 ±60 before present, and a corrected originally reported from Cueva Ceiba (next apparently shortly after the coming of calendar age of 1525 AD, (1 sigma range to Utuado, P.R.) in 1916 by J. A. Allen (1916), European explorers, according to most 1480-1655 AD). This date coincides with the and it is known today only by skeletal remains historians. final occupation of Isla de Mona by the Taino from Hispaniola (Dominican Republic, Haiti, The first person to take an interest in the Indians (1578 AD; Wadsworth 1977). The Île de la Gonâve, ÎIe de la Tortue), Puerto faunal remains of the caves of Isla de Mona purpose of this article is to report some new Rico (mainland, Isla de Mona, Caja de was mammalogist Harold E. Anthony, who paleontological discoveries of the Puerto Muertos, Vieques), the Virgin Islands (St. in 1926 collected the first Puerto Rican hutia Rican hutia in cave deposits of Isla de Mona Croix, St. -

Harrisia Cactus Moonlight Cactus Harrisia Martinii, Harrisia Tortuosa and Harrisia Pomanensis

Restricted invasive plant Harrisia cactus Moonlight cactus Harrisia martinii, Harrisia tortuosa and Harrisia pomanensis Harrisia cactus can form dense infestations that will Legal requirements reduce pastures to a level unsuitable for stock. Harrisia cactus will choke out other pasture species Harrisia cactus (Harrisia martinii, Harrisia tortuosa and when left unchecked. Harrisia pomanensis) are category 3 restricted invasive plants under the Biosecurity Act 2014. It must not be The spines are a problem for stock management, given away, sold, or released into the environment. The interfering with mustering and stock movement. Act requires everyone to take all reasonable and practical Harrisia cactus produces large quantities of seed that is steps to minimise the risks associated with invasive plants highly viable and easily spread by birds and other animals. under their control. This is called a general biosecurity As well as reproducing from seed, harrisia cactus has long obligation (GBO). This fact sheet gives examples of how trailing branches that bend and take root wherever they you can meet your GBO. touch the ground. Any broken-off portions of the plant will take root and grow. At a local level, each local government must have a The cactus is shade tolerant and reaches its maximum biosecurity plan that covers invasive plants in its area. development in the shade and shelter of brigalow scrub, This plan may include actions to be taken on certain though established infestations can persist once scrub species. Some of these actions may be required under is pulled. local laws. Contact your local government for more Harrisia cactus is found in the Collinsville, Nebo, information. -

University of Florida Thesis Or Dissertation Formatting

SYSTEMATICS OF TRIBE TRICHOCEREEAE AND POPULATION GENETICS OF Haageocereus (CACTACEAE) By MÓNICA ARAKAKI MAKISHI A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2008 1 © 2008 Mónica Arakaki Makishi 2 To my parents, Bunzo and Cristina, and to my sisters and brother. 3 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I want to express my deepest appreciation to my advisors, Douglas Soltis and Pamela Soltis, for their consistent support, encouragement and generosity of time. I would also like to thank Norris Williams and Michael Miyamoto, members of my committee, for their guidance, good disposition and positive feedback. Special thanks go to Carlos Ostolaza and Fátima Cáceres, for sharing their knowledge on Peruvian Cactaceae, and for providing essential plant material, confirmation of identifications, and their detailed observations of cacti in the field. I am indebted to the many individuals that have directly or indirectly supported me during the fieldwork: Carlos Ostolaza, Fátima Cáceres, Asunción Cano, Blanca León, José Roque, María La Torre, Richard Aguilar, Nestor Cieza, Olivier Klopfenstein, Martha Vargas, Natalia Calderón, Freddy Peláez, Yammil Ramírez, Eric Rodríguez, Percy Sandoval, and Kenneth Young (Peru); Stephan Beck, Noemí Quispe, Lorena Rey, Rosa Meneses, Alejandro Apaza, Esther Valenzuela, Mónica Zeballos, Freddy Centeno, Alfredo Fuentes, and Ramiro Lopez (Bolivia); María E. Ramírez, Mélica Muñoz, and Raquel Pinto (Chile). I thank the curators and staff of the herbaria B, F, FLAS, LPB, MO, USM, U, TEX, UNSA and ZSS, who kindly loaned specimens or made information available through electronic means. Thanks to Carlos Ostolaza for providing seeds of Haageocereus tenuis, to Graham Charles for seeds of Blossfeldia sucrensis and Acanthocalycium spiniflorum, to Donald Henne for specimens of Haageocereus lanugispinus; and to Bernard Hauser and Kent Vliet for aid with microscopy. -

Two New Scorpions from the Puerto Rican Island of Vieques, Greater Antilles (Scorpiones: Buthidae)

Two new scorpions from the Puerto Rican island of Vieques, Greater Antilles (Scorpiones: Buthidae) Rolando Teruel, Mel J. Rivera & Carlos J. Santos September 2015 — No. 208 Euscorpius Occasional Publications in Scorpiology EDITOR: Victor Fet, Marshall University, ‘[email protected]’ ASSOCIATE EDITOR: Michael E. Soleglad, ‘[email protected]’ Euscorpius is the first research publication completely devoted to scorpions (Arachnida: Scorpiones). Euscorpius takes advantage of the rapidly evolving medium of quick online publication, at the same time maintaining high research standards for the burgeoning field of scorpion science (scorpiology). Euscorpius is an expedient and viable medium for the publication of serious papers in scorpiology, including (but not limited to): systematics, evolution, ecology, biogeography, and general biology of scorpions. Review papers, descriptions of new taxa, faunistic surveys, lists of museum collections, and book reviews are welcome. Derivatio Nominis The name Euscorpius Thorell, 1876 refers to the most common genus of scorpions in the Mediterranean region and southern Europe (family Euscorpiidae). Euscorpius is located at: http://www.science.marshall.edu/fet/Euscorpius (Marshall University, Huntington, West Virginia 25755-2510, USA) ICZN COMPLIANCE OF ELECTRONIC PUBLICATIONS: Electronic (“e-only”) publications are fully compliant with ICZN (International Code of Zoological Nomenclature) (i.e. for the purposes of new names and new nomenclatural acts) when properly archived and registered. All Euscorpius issues starting from No. 156 (2013) are archived in two electronic archives: Biotaxa, http://biotaxa.org/Euscorpius (ICZN-approved and ZooBank-enabled) Marshall Digital Scholar, http://mds.marshall.edu/euscorpius/. (This website also archives all Euscorpius issues previously published on CD-ROMs.) Between 2000 and 2013, ICZN did not accept online texts as "published work" (Article 9.8). -

South American Cacti in Time and Space: Studies on the Diversification of the Tribe Cereeae, with Particular Focus on Subtribe Trichocereinae (Cactaceae)

Zurich Open Repository and Archive University of Zurich Main Library Strickhofstrasse 39 CH-8057 Zurich www.zora.uzh.ch Year: 2013 South American Cacti in time and space: studies on the diversification of the tribe Cereeae, with particular focus on subtribe Trichocereinae (Cactaceae) Lendel, Anita Posted at the Zurich Open Repository and Archive, University of Zurich ZORA URL: https://doi.org/10.5167/uzh-93287 Dissertation Published Version Originally published at: Lendel, Anita. South American Cacti in time and space: studies on the diversification of the tribe Cereeae, with particular focus on subtribe Trichocereinae (Cactaceae). 2013, University of Zurich, Faculty of Science. South American Cacti in Time and Space: Studies on the Diversification of the Tribe Cereeae, with Particular Focus on Subtribe Trichocereinae (Cactaceae) _________________________________________________________________________________ Dissertation zur Erlangung der naturwissenschaftlichen Doktorwürde (Dr.sc.nat.) vorgelegt der Mathematisch-naturwissenschaftlichen Fakultät der Universität Zürich von Anita Lendel aus Kroatien Promotionskomitee: Prof. Dr. H. Peter Linder (Vorsitz) PD. Dr. Reto Nyffeler Prof. Dr. Elena Conti Zürich, 2013 Table of Contents Acknowledgments 1 Introduction 3 Chapter 1. Phylogenetics and taxonomy of the tribe Cereeae s.l., with particular focus 15 on the subtribe Trichocereinae (Cactaceae – Cactoideae) Chapter 2. Floral evolution in the South American tribe Cereeae s.l. (Cactaceae: 53 Cactoideae): Pollination syndromes in a comparative phylogenetic context Chapter 3. Contemporaneous and recent radiations of the world’s major succulent 86 plant lineages Chapter 4. Tackling the molecular dating paradox: underestimated pitfalls and best 121 strategies when fossils are scarce Outlook and Future Research 207 Curriculum Vitae 209 Summary 211 Zusammenfassung 213 Acknowledgments I really believe that no one can go through the process of doing a PhD and come out without being changed at a very profound level. -

ATOLL RESEARCH BULLETIN NO. 251 BIOGEOGRAPHY of the PUERTO RICAN BANK by Harold Heatwole, Richard Levins and Michael D. Byer

ATOLL RESEARCH BULLETIN NO. 251 BIOGEOGRAPHY OF THE PUERTO RICAN BANK by Harold Heatwole, Richard Levins and Michael D. Byer Issued by THE SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION Washington, D. C., U.S.A. July 1981 VIRGIN ISLANDS CULEBRA PUERTO RlCO Fig. 1. Map of the Puerto Rican Island Shelf. Rectangles A - E indicate boundaries of maps presented in more detail in Appendix I. 1. Cayo Santiago, 2. Cayo Batata, 3. Cayo de Afuera, 4. Cayo de Tierra, 5. Cardona Key, 6. Protestant Key, 7. Green Key (st. ~roix), 8. Caiia Azul ATOLL RESEARCH BULLETIN 251 ERRATUM The following caption should be inserted for figure 7: Fig. 7. Temperature in and near a small clump of vegetation on Cayo Ahogado. Dots: 5 cm deep in soil under clump. Circles: 1 cm deep in soil under clump. Triangles: Soil surface under clump. Squares: Surface of vegetation. X's: Air at center of clump. Broken line indicates intervals of more than one hour between measurements. BIOGEOGRAPHY OF THE PUERTO RICAN BANK by Harold Heatwolel, Richard Levins2 and Michael D. Byer3 INTRODUCTION There has been a recent surge of interest in the biogeography of archipelagoes owing to a reinterpretation of classical concepts of evolution of insular populations, factors controlling numbers of species on islands, and the dynamics of inter-island dispersal. The literature on these subjects is rapidly accumulating; general reviews are presented by Mayr (1963) , and Baker and Stebbins (1965) . Carlquist (1965, 1974), Preston (1962 a, b), ~ac~rthurand Wilson (1963, 1967) , MacArthur et al. (1973) , Hamilton and Rubinoff (1963, 1967), Hamilton et al. (1963) , Crowell (19641, Johnson (1975) , Whitehead and Jones (1969), Simberloff (1969, 19701, Simberloff and Wilson (1969), Wilson and Taylor (19671, Carson (1970), Heatwole and Levins (1973) , Abbott (1974) , Johnson and Raven (1973) and Lynch and Johnson (1974), have provided major impetuses through theoretical and/ or general papers on numbers of species on islands and the dynamics of insular biogeography and evolution. -

Us Caribbean Regional Coral Reef Fisheries Management Workshop

Caribbean Regional Workshop on Coral Reef Fisheries Management: Collaboration on Successful Management, Enforcement and Education Methods st September 30 - October 1 , 2002 Caribe Hilton Hotel San Juan, Puerto Rico Workshop Objective: The regional workshop allowed island resource managers, fisheries educators and enforcement personnel in Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands to identify successful coral reef fishery management approaches. The workshop provided the U.S. Coral Reef Task Force with recommendations by local, regional and national stakeholders, to develop more effective and appropriate regional planning for coral reef fisheries conservation and sustainable use. The recommended priorities will assist Federal agencies to provide more directed grant and technical assistance to the U.S. Caribbean. Background: Coral reefs and associated habitats provide important commercial, recreational and subsistence fishery resources in the United States and around the world. Fishing also plays a central social and cultural role in many island communities. However, these fishery resources and the ecosystems that support them are under increasing threat from overfishing, recreational use, and developmental impacts. This workshop, held in conjunction with the U.S. Coral Reef Task Force Meeting, brought together island resource managers, fisheries educators and enforcement personnel to compare methods that have been successful, including regulations that have worked, effective enforcement, and education to reach people who can really effect change. These efforts were supported by Federal fishery managers and scientists, Puerto Rico Sea Grant, and drew on the experience of researchers working in the islands and Florida. The workshop helped develop approaches for effective fishery management strategies in the U.S. Caribbean and recommended priority actions to the U.S. -

Redalyc.Stem and Root Anatomy of Two Species of Echinopsis

Revista Mexicana de Biodiversidad ISSN: 1870-3453 [email protected] Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México México dos Santos Garcia, Joelma; Scremin-Dias, Edna; Soffiatti, Patricia Stem and root anatomy of two species of Echinopsis (Trichocereeae: Cactaceae) Revista Mexicana de Biodiversidad, vol. 83, núm. 4, diciembre, 2012, pp. 1036-1044 Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México Distrito Federal, México Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=42525092001 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative Revista Mexicana de Biodiversidad 83: 1036-1044, 2012 DOI: 10.7550/rmb.28124 Stem and root anatomy of two species of Echinopsis (Trichocereeae: Cactaceae) Anatomía de la raíz y del tallo de dos especies de Echinopsis (Trichocereeae: Cactaceae) Joelma dos Santos Garcia1, Edna Scremin-Dias1 and Patricia Soffiatti2 1Universidade Federal de Mato Grosso do Sul, CCBS, Departamento de Biologia, Programa de Pós Graduação em Biologia Vegetal Cidade Universitária, S/N, Caixa Postal 549, CEP 79.070.900 Campo Grande, MS, Brasil. 2Universidade Federal do Paraná, SCB, Departamento de Botânica, Programa de Pós-Graduação em Botânica, Caixa Postal 19031, CEP 81.531.990 Curitiba, PR, Brasil. [email protected] Abstract. This study characterizes and compares the stem and root anatomy of Echinopsis calochlora and E. rhodotricha (Cactaceae) occurring in the Central-Western Region of Brazil, in Mato Grosso do Sul State. Three individuals of each species were collected, fixed, stored and prepared following usual anatomy techniques, for subsequent observation in light and scanning electronic microscopy. -

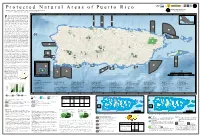

Protected Areas by Management 9

Unted States p Forest Department a Service DRNA of Agriculture g P r o t e c t e d N a t u r a l A r e a s o f P u e r to R i c o K E E P I N G C O M M ON S P E C I E S C O M M O N PRGAP ANALYSIS PROJECT William A. Gould, Maya Quiñones, Mariano Solórzano, Waldemar Alcobas, and Caryl Alarcón IITF GIS and Remote Sensing Lab A center for tropical landscape analysis U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, International Institute of Tropical Forestry . o c 67°30'0"W 67°20'0"W 67°10'0"W 67°0'0"W 66°50'0"W 66°40'0"W 66°30'0"W 66°20'0"W 66°10'0"W 66°0'0"W 65°50'0"W 65°40'0"W 65°30'0"W 65°20'0"W i R o t rotection of natural areas is essential to conserving biodiversity and r e u P maintaining ecosystem services. Benefits and services provided by natural United , Protected areas by management 9 States 1 areas are complex, interwoven, life-sustaining, and necessary for a healthy A t l a n t i c O c e a n 1 1 - 6 environment and a sustainable future (Daily et al. 1997). They include 2 9 0 clean water and air, sustainable wildlife populations and habitats, stable slopes, The Bahamas 0 P ccccccc R P productive soils, genetic reservoirs, recreational opportunities, and spiritual refugia. -

Anidación De La Tortuga Carey (Eretmochelys Imbricata) En Isla De Mona, Puerto Rico

Anidación de la tortuga carey (Eretmochelys imbricata) en Isla de Mona, Puerto Rico. Carlos E. Diez 1, Robert P. van Dam 2 1 DRNA-PR PO Box 9066600 Puerta de Tierra San Juan, PR 00906 [email protected] 2 Chelonia Inc PO Box 9020708 San Juan, PR 00902 [email protected] Palabras claves: Reptilia, carey de concha, Eretmochelys imbricata, anidación, tortugas marinas, marcaje, conservación, Caribe, Isla de Mona, Puerto Rico. Resumen El carey de concha, Eretmochelys imbricata, es la especie de tortuga marina más abundante en nuestras playas y costas. Sin embargo está clasificada como una especie en peligro de extinción por leyes estatales y federales además de estar protegida a nivel internacional. Uno de los lugares más importantes del Caribe para la reproducción de esta especie es en la Isla de Mona, Puerto Rico. Los resultados del monitoreo de la actividad de anidaje en la Isla de Mona han demostrado un incremento siginificativo en el números de nidos de la tortuga carey depositado en la isla durante los últimos años. En el año 2005 se contó un total de 1003 nidos de carey depositados en todas las playas de Isla de Mona durante 116 días de monitoreo, lo cual es una cantidad mayor que durante cualquier censo en años anteriores (en 1994 se contaron 308 nidos depositados en 114 días). De igual manera, el Índice de Actividades de Anidaje cual esta basado en conteos precisos durante 60 dias aumento a partir de su estableciemiento en el 2003 con 298 nidos de carey con 18% a 353 nidos en 2004 y resultando en 368 nidos en el 2005. -

Reconnaissance Investigation of Caribbean Extreme Wave Deposits – Preliminary Observations, Interpretations, and Research Directions

RECONNAISSANCE INVESTIGATION OF CARIBBEAN EXTREME WAVE DEPOSITS – PRELIMINARY OBSERVATIONS, INTERPRETATIONS, AND RESEARCH DIRECTIONS Robert A. Morton, Bruce M. Richmond, Bruce E. Jaffe, and Guy Gelfenbaum Open-File Report 2006-1293 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Cover photograph – Panorama view on the north coast of Bonaire at Boka Kokolishi in March 2006 showing (from left to right), Caribbean Sea, modern sea cliff, scattered boulders and sand deposits on an elevated rock platform, and a paleo-seacliff. Wave swept zone and fresh sand deposits were products of Hurricane Ivan in September 2004. RECONNAISSANCE INVESTIGATION OF CARIBBEAN EXTREME WAVE DEPOSITS – PRELIMINARY OBSERVATIONS, INTERPRETATIONS, AND RESEARCH DIRECTIONS 1 2 2 3 Robert A. Morton , Bruce M. Richmond , Bruce E. Jaffe , and Guy Gelfenbaum 1U.S. Geological Survey, 600 Fourth St. S., St. Petersburg, FL 33701 2U.S. Geological Survey, 400 Natural Bridges Drive, Santa Cruz, CA 95060 USA 3U.S. Geological Survey, 345 Middlefield Rd., Menlo Park, CA 94025 USA Open-File Report 2006-1293 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey i Contents SUMMARY ...........................................................................................................................................................................1 INTRODUCTION...................................................................................................................................................................1 GENERAL GEOLOGIC SETTING .........................................................................................................................................1