Historical Landscape of Stourbridges Green Belt

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Black Country Urban Park Barometer

3333333 Black Country Urban Park Barometer April 2013 DRAFT WORK IN PROGRESS Welcome to the Black Country Urban Park Barometer. Transformation of the Environmental Infrastructure is one of the key to drivers identified in the Black Country Strategy for Growth and Competitiveness. The full report looks at the six themes created under the ‘Urban Park’ theme and provides a spatial picture of that theme accompanied with the key assets and opportunities for that theme. Foreword to be provided by Roger Lawrence The Strategic Context Quality of the Black Country environment is one of the four primary objectives of the Black Country Vision that has driven the preparation of the Black Country Strategy for Growth and Competitiveness through the Black Country Study process. The environment is critical to the health and well-being of future residents, workers and visitors to the Black Country. It is also both a major contributor to, and measure of, wider goals for sustainable development and living as well as being significantly important to the economy of the region. The importance and the desire for transforming the Black Country environment has been reinforced through the evidence gathering and analysis of the Black Country Study process as both an aspiration in its own right and as a necessity to achieve economic prosperity. Evidence from the Economic and Housing Studies concluded that ‘the creation of new environments will be crucial for attracting investment from high value-added firms’ and similarly that ‘a high quality healthy environment is a priority for ‘knowledge workers’. The Economic Strategy puts ‘Environmental Transformation’ alongside Education & Skills as the fundamental driver to achieve Black Country economic renaissance and prosperity for its people. -

The Parentage of Anne Henzey

The Parentage of Anne Henzey On July 1st, 1675 “Mr Samuel Ward, Rector of Strensham & Mrs Anne Henzey of Amblecoat in ye parish of Oldswinford” were married at Pedmore, Worcestershire. Their Marriage Allegation, dated 23 Jun 1675, gives further information: “Mr Samuel Warde Rector of Strensham ... aged 34 years or thereabouts a Batchelor ...[and] Anne Henzey of the parish of Oldswinford ... aged 20 years or thereabouts and a maiden their parents livinge on both sides and to the intended marriage consenting ...” Samuel and Anne Ward had three children, two daughters, Ann and Elizabeth, baptised in 1676 and 1678, and one son, Paul, baptised and buried in 1680. Family naming patterns suggest that Ann would be the name of the wife’s mother, or less commonly that of the husband’s mother, and that Paul would be the name of the husband’s father, or less commonly that of the wife’s father, particularly if the wife’s father was wealthy. The only one of these names to appear in Samuel Ward’s family before 1680 was Elizabeth, which was the name of his sister-in-law and niece. Samuel’s parents, both of whom were living in Coventry in 1675, were named Samuel and Joan. 1 It can therefore be established that Anne Henzey was probably born between June 1654 and June 1655, that she came from Amblecoat in the parish of Oldswinford, Worcestershire, and that both her parents were living in 1675. It is also probable that the names Paul and Anne appeared in the family, possibly as Anne’s parents. -

A Cornerstone of the Historical Landscape

Stourbridge's Western Boundary: A cornerstone of the historical landscape by K James BSc(Hons) MSc PhD FIAP (email: [email protected]) The present-day administrative boundaries around Stourbridge are the result of a long and complex series of organizational changes, land transfers and periods of settlement, invasion and warfare dating back more than two thousand years. Perhaps the most interesting section of the boundary is that to the west of Stourbridge which currently separates Dudley Metropolitan Borough from Kinver in Staffordshire. This has been the county boundary for a millennium, and its course mirrors the outline of the medieval manors of Oldswinford and Pedmore; the Domesday hundred of Clent; Anglo-Saxon royal estates, the Norman forest of Kinver and perhaps the 7th-9th century Hwiccan kingdom as well as post-Roman tribal territories. The boundary may even have its roots in earlier (though probably more diffuse) frontiers dating back to prehistoric times. Extent and Description As shown in figure 1, the boundary begins at the southern end of County Lane near its junction with the ancient road (now just a rough public footpath) joining Iverley to Ounty John Lane. It follows County Lane north-north-west, crosses the A451 and then follows the line of Sandy Lane (now a bridleway) to the junction of Sugar Loaf Lane and The Broadway. Along with County Lane, this section of Sandy Lane lies upon a first-century Roman road that connected Droitwich (Salinae) to the Roman encampments at Greensforge near Ashwood. Past Sugar Loaf Lane, the line of the boundary diverges by a few degrees to the east of the Roman road, which continues on in a straight line under the fields of Staffordshire towards Newtown Bridge and Prestwood. -

The Grove Family of Halesowen

THE GROVE FAMILY OF HALESOWEN BY JAMES DAVENPORT, M.A., F.S.A., RECTOR OF HARVlNGTON METHUEN & CO., LTD. 36 ESSEX STREET, W.C. LONDON BY THE SAME AUTHOR THE WASHBOURNE FAMILY OF LITTLE WASHBOURNE AND WICHENFORD. PREFACE ·My best thanks are accorded to G. F. Adams, Esq., Registrar of the Worcester Probate Registry, for access to Wills in his keeping ; to Tohn H. Hooper, Esq., M.A., Registrar of the Diocese of Worcester, for permission to study the Transcripts at Edgar Tower ; to the Rector of Hales owen for access to the Registers there, and to others who have kindly supplied information asked for. In preparing these notes I have relied upon the Printed Register of Halesowen (1559-1643) brought out by the Parish Register Society, and desire to express my indebtedness to the Society and to the labours or the transcriber. J. D. HARVINGTON RECTORY EVESHAM C·ONTENTS PAGE INTRODUCTION Xl GENEALOGICAL TABLE XVll CHAPTER I. DESCENDANTS OF JoHN GROVE (LIVING 1538) THROUGH HIS GRANDSON JOHN I CHAPTER II. DESCENDANTS OF THE SAME JOHN THROUGH HIS OTHER GRANDSONS, THOMAS, WILLIAM, RICHARD, AND GEORGE APPENDIX A. WILLS, ETC., OF UNIDENTIFIED MEMBERS OF THE HALESOWEN FAMILY (1540- 1784) · 71 APPENDIX B. THE PEARSALL AND PESHAL FAMILIES. 75 APPENDIX C. EARLIEST WILLS OF HAGLEY, RowLEY, OLDSWINFORD, AND KINGSNORTON BRANCHES 78 INDEX 81 iz INTRODUCTION HE origin of the Grove family, stationed for many T centuries in the extreme north of the present county of Worcester and still represented there, is lost in antiquity. The early Court Rolls of Halesowen, now being transcribed and edited for the Worcestershire Historical Society by Mr. -

Dudley Metropolitan Borough Council Polling Station List

Dudley Metropolitan Borough Council Polling Station List European Parliamentary Election Thursday 23 May 2019 Reference Address Districts 1 Foxyards Primary School, Foxyards Road, Tipton, West Midlands, A01 DY4 8BH 2 Caravan, Forest Road, Dudley, West Midlands, DY1 4BX A02 3 Sea Cadet H Q, Tipton Road, Dudley, West Midlands, DY1 4SQ A03 4 Ward Room, Priory Hall, Training Centre, Dudley, West Midlands, A04 DY1 4EU 5 Priory Primary School, Entrance In Cedar Road and Limes Road, A05 Dudley, West Midlands, DY1 4AQ 6 Reception Block Bishop Milner R C School, (Car Access The A06 Broadway), Burton Road, Dudley, West Midlands, DY1 3BY 7 Midlands Co-Op, Dibdale Road West, Milking Bank, Dudley, DY1 A07 2RH 8 Sycamore Green Centre, Sycamore Green, Dudley, West Midlands, A08,G04 DY1 3QE 9 Wrens Nest Primary School, Marigold Crescent, Dudley, West A09 Midlands, DY1 3NQ 10 Priory Community Centre, Priory Road, Dudley, West Midlands, DY1 A10 4ED 11 Rainbow Community Centre, 49 Rainbow Street, Coseley, West B01 Midlands, WV14 8SX 12 Summerhill Community Centre, 28B Summerhill Road, Coseley, B02 West Midlands, WV14 8RD 13 Wallbrook Primary School, Bradleys Lane, Coseley, West Midlands, B03 WV14 8YP 14 Coseley Youth Centre, Clayton Park, Old Meeting Road, Coseley, B04 WV14 8HB 15 Foundation Years Unit, Christ Church Primary School, Church Road, B05 Coseley, WV14 8YB 16 Roseville Methodist Church Hall, Bayer Street, Coseley, West B06 Midlands, WV14 9DS 17 Activity Centre, Silver Jubilee Park, Mason Street, Coseley, WV14 B07 9SZ 18 Hurst Hill Primary School, -

Mondays to Fridays Saturdays Sundays

192 Halesowen - Hagley - Kidderminster Diamond Bus The information on this timetable is expected to be valid until at least 19th October 2021. Where we know of variations, before or after this date, then we show these at the top of each affected column in the table. Direction of stops: where shown (eg: W-bound) this is the compass direction towards which the bus is pointing when it stops Mondays to Fridays Halesowen, Halesowen Bus Station (Stand E) 0735 0920 20 1520 1630 1730 1830 § Halesowen, Blackberry Lane (Adjacent 1) 0736 0921 21 1521 1631 1731 1831 § Hasbury, School Lane (Adjacent 2) 0737 0922 22 1522 1632 1732 1832 § Hasbury, Albert Road (Opposite 2) 0738 0923 23 1523 1633 1733 1833 § Hasbury, Uffmoor Lane (Adjacent 2) 0739 0924 24 1524 1634 1734 1834 § Hayley Green, nr Cherry Tree Lane 0740 0925 25 1525 1635 1735 1835 § Hayley Green, adj Waugh Drive 0741 0926 26 1526 1636 1736 1836 § Hayley Green, opp Lutley Lane 0742 0927 27 1527 1637 1737 1837 Hagley, adj Hagley Golf Course 0745 0930 30 1530 1640 1740 1840 § Hagley, opp Wassell Grove Road 0745 0930 30 1530 1640 1740 1840 § Hagley, adj School Lane 0746 0931 31 1531 1641 1741 1841 § Hagley, adj Paramount Showrooms 0746 0931 31 1531 1641 1741 1841 § Hagley, adj Hagley Primary School 0746 0931 31 1531 1641 1741 1841 § Hagley, Station Road (W-bound) 0747 0932 32 1532 1642 1742 1842 then § West Hagley, opp Free Church 0747 0932 32 1532 1642 1742 1842 at § West Hagley, opp Summervale Road 0747 0932 32 1532 1642 1742 1842 these § West Hagley, Newfield Road (S-bound) 0747 0932 32 1532 -

Dudley in the County of West Midlands

LOCAL BOUNDARY FOR ENGLAND REPORT HO. LOCAL G BOUNDARY FOR ENGLAND NO. LOCAL OOVKKNKKUT BOUNDARY CO','MISSION FOK fc.'GLAUD CHAIRMAN Sir Nicholas Morrison KCB DEPUTY CHAIRMAN Mr J M Rankin QC MEM3EHS Lady Bowden Mr J T Brockbank Mr R R Thornton CB DL Mr D P Harrison Professor G E Cherry Secretary of State for the Home Department PROPOSALS FOR REVISED ELECTORAL ARRANGEMEMTS FOR THE METROPOLITAN BOROUGH OF DUDLEY IN THE COUNTY OF WEST MIDLANDS 1. We, the Local Government Boundary Commission for England, having carried out our initial review of the electoral arrangements for the metropolitan borough of Dudley in accordance with the requirements of section 63 of, and Schedule 9 to, the Local Government Act 1972, present our proposals for the future electoral arrangements for that borough. 2. In accordance with the procedure laid down in section 60(l) and (2) of the 1972 Act, notice was given on 8 August 1975 that we were to undertake this review. This was incorporated in a consultation letter addressed to the Dudley Borough Council, copies of which were circulated to the West Midlands County Council, the Members of Parliament for the constituencies concerned, and the headquarters of the main political parties. Copies were also sent to the editors of local newspapers circulating in the area and of the local government press. Notices inserted in the local press announced the start of the review and invited comments from members of the public and from interested bodies, 3. Dudley Borough Council were invited to prepare a draft scheme of representation for our consideration. -

Chapter 1. the Labourer and the Land: Enclosure in Worcestershire 1790-1829

CHAPTER 1. THE LABOURER AND THE LAND: ENCLOSURE IN WORCESTERSHIRE 1790-1829 It is now generally accepted that enclosure in eighteenth-century England had a fundamental impact on the majority of agricultural labourers and was a key factor in their long decline from independent or semi-independent cottagers to impoverished and dependent day labourers. In the first half of the twentieth century there was a long-standing historical debate about enclosure that sprang partly from ideology and partly from arguments originally expressed by opponents of enclosure in the eighteenth century. As early as 1766, for example, Aris’ Birmingham Gazette warned its readers about rural depopulation resulting from farmers changing much of their land from arable to pasture and too many landowners using farmland for raising game.1 By the time the Hon. John Byng, (later Fifth Viscount Torrington) toured England and Wales between 1781 and 1794, the situation appeared to be even worse. At Wallingford, Oxfordshire, in 1781, Byng noted how enclosure enabled ‘the greedy tyrannies of the wealthy few to oppress the indigent many’ thus leading to rural depopulation and a decline in rural customs and traditions. A few years later, in Derbyshire in 1789, Byng lamented the fact that landlords had abdicated all responsibility to their tenants, leading to the growth of village poverty and a rise in the poor rates. One old woman told him how her cottage which she had rented for 50s a year had been swallowed up by enclosure and with it her garden and bee hives, her share in a flock of sheep, feed for her geese and fuel for her fire. -

Wednesbury to Brierley Hill Metro Extension Business Case

Wednesbury to Brierley Hill Business Case Midland Metro Wednesbury to Brierley Hill Extension June 2017 The Midland Metro Alliance is a team of planning, design and construction specialists responsible for building a number of new tram extensions over the coming decade on behalf of the West Midlands Combined Authority. These exciting extensions will help deliver a lasting legacy, aiding social and economic regeneration across the region. Building on lessons from past projects and best practice from across the world, Midland Metro Alliance has goals which will ensure the 10 year plan will only be successfully delivered if all parties work together. This will give the best outcome for the travelling public and the local economy. ~,WEST MIDLAo DS TfW M WEST MIDLANDS `~ ♦-~- - -~-~-~ COMBINED AUTHORITY FOREWORD BY ANDY STREET — MAYOR FOR THE WEST MIDLANDS As the newly elected Mayor for the West Midlands, I am delighted to submit to you this Business Case for the Wednesbury to Brierley Hill Extension of the Midland Metro. One of my key manifesto promises was to start work on this extension within my first term, and this important first step, seeking to obtain the funding and approvals from Central Government, is one that ~I am proud to take within my first month as Mayor. NDS This route will be a key part of the tram network across the region, ■ ~ which will play a significant role in the regeneration and economic growth for the West Midlands. Our patronage on the existing service between Birmingham and Wolverhampton city centres is at an all-time high — 7.89 million passengers took the tram between June 2016 and May 2017. -

Vebraalto.Com

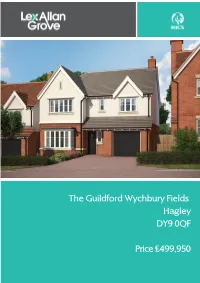

The Guildford Wychbury Fields Hagley DY9 0QF Price £499,950 In a picturesque setting at the foot of Clent Hills, our exclusive Wychbury Fields development of two, three, four and five bedroom homes enjoy an open outlook, with some offering views towards the Malvern Hills. Generous in space and scope, as well as boasting high specification throughout, these light and airy homes benefit from a wealth of local amenities and respected schools. While the commuting and entertaining appeal of Birmingham is only a short 15-mile drive away. Commuting from this desirable semi-rural retreat is just as convenient. Whether the office, family or school run calls, you can be there in next to no time, with access to Junction 3 of the M5 located about six miles away from Hagley taking you straight to the city centre. Or you can take advantage of the direct trains from Hagley station to Birmingham Moor Street in around 34 minutes, as well as to Worcester, Solihull and Cheltenham. Regular buses also run to Stourbridge via A491 and Kidderminster on the A456. The sought-after village of Hagley can be found just to the south of Stourbridge on the Worcestershire border. An affluent and leafy residential suburb, it’s also home to a lovely choice of independent shops, country pubs and fashionable eateries. Famous for glass production, Stourbridge offers a wealth of banks, high street stores and supermarkets including Waitrose, together with popular bars and restaurants. While Merry Hill Shopping Centre in Dudley is about seven miles away and the city buzz of Birmingham is a little further. -

Application Dossier for the Proposed Black Country Global Geopark

Application Dossier For the Proposed Black Country Global Geopark Page 7 Application Dossier For the Proposed Black Country Global Geopark A5 Application contact person The application contact person is Graham Worton. He can be contacted at the address given below. Dudley Museum and Art Gallery Telephone ; 0044 (0) 1384 815575 St James Road Fax; 0044 (0) 1384 815576 Dudley West Midlands Email; [email protected] England DY1 1HP Web Presence http://www.dudley.gov.uk/see-and-do/museums/dudley-museum-art-gallery/ http://www.blackcountrygeopark.org.uk/ and http://geologymatters.org.uk/ B. Geological Heritage B1 General geological description of the proposed Geopark The Black Country is situated in the centre of England adjacent to the city of Birmingham in the West Midlands (Figure. 1 page 2) .The current proposed geopark headquarters is Dudley Museum and Art Gallery which has the office of the geopark coordinator and hosts spectacular geological collections of local fossils. The geological galleries were opened by Charles Lapworth (founder of the Ordovician System) in 1912 and the museum carries out annual programmes of geological activities, exhibitions and events (see accompanying supporting information disc for additional detail). The museum now hosts a Black Country Geopark Project information point where the latest information about activities in the geopark area and information to support a visit to the geopark can be found. Figure. 7 A view across Stone Street Square Dudley to the Geopark Headquarters at Dudley Museum and Art Gallery For its size, the Black Country has some of the most diverse geology anywhere in the world. -

Guide to Resources in the Archive Self Service Area

Worcestershire Archive and Archaeology Service www.worcestershire.gov.uk/waas Guide to Resources in the Archive Self Service Area 1 Contents 1. Introduction to the resources in the Self Service Area .............................................................. 3 2. Table of Resources ........................................................................................................................ 4 3. 'See Under' List ............................................................................................................................. 23 4. Glossary of Terms ........................................................................................................................ 33 2 1. Introduction to the resources in the Self Service Area The following is a guide to the types of records we hold and the areas we may cover within the Self Service Area of the Worcestershire Archive and Archaeology Service. The Self Service Area has the same opening hours as the Hive: 8.30am to 10pm 7 days a week. You are welcome to browse and use these resources during these times, and an additional guide called 'Guide to the Self Service Archive Area' has been developed to help. This is available in the area or on our website free of charge, but if you would like to purchase your own copy of our guides please speak to a member of staff or see our website for our current contact details. If you feel you would like support to use the area you can book on to one of our workshops 'First Steps in Family History' or 'First Steps in Local History'. For more information on these sessions, and others that we hold, please pick up a leaflet or see our Events Guide at www.worcestershire.gov.uk/waas. About the Guide This guide is aimed as a very general overview and is not intended to be an exhaustive list of resources.