Chapter 1. the Labourer and the Land: Enclosure in Worcestershire 1790-1829

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dogs and Footpaths We Have Been Asked by Local Landowners to Remind You All of the Importance of Keeping Dogs on Leads, Or in Close Control When Near Livestock

Christmas 2017 Keep in touch with village life at www.ashtonunderhill.org.uk and on www.facebook.com/AshtonunderHillParishCouncil The Ashton Under Hill table- tennis team (Seniors and Juniors) recently competed in the Parish Games at St Egwins School following an intensive training programme over the summer. The event was very well Would you like to organised and the protect your home competitive table tennis from theft? For more community of Wychavon was information, see P5. in full attendance. For more information see P6. Dogs and footpaths We have been asked by local landowners to remind you all of the importance of keeping dogs on leads, or in close control when near livestock. The landowners love to see walkers on the hill or surrounding countryside enjoying our lovely open spaces and this is a plea to support them, so please don’t take this as a warning to stay away. There have been a few issues when walkers have felt upset or intimidated when they have been asked to stay on paths and keep dogs under control. Livestock get very distressed if chased by dogs, particularly the sheep in the fields and on the hill. When ewes are in lamb, this is particularly dangerous; but there are also regularly incidents where sheep with injured legs etc have had to be put down. This is all farmland that has designated footpaths. Please consider the farmers when walking your dogs, but please continue to enjoy the Hill. Thank you all. For more information please visit this website: www.ramblers.org.uk/advice/rights-of-way-law-in- england-and-wales/animals-and-rights-of-way.aspx#dogs CATCH Project Appeal Thanks to the great generosity of Ashton residents, at the time of going to press we will have raised £7,055 for the CATCH Project in Mzamomhle, South Africa, between July and September this year. -

A Cornerstone of the Historical Landscape

Stourbridge's Western Boundary: A cornerstone of the historical landscape by K James BSc(Hons) MSc PhD FIAP (email: [email protected]) The present-day administrative boundaries around Stourbridge are the result of a long and complex series of organizational changes, land transfers and periods of settlement, invasion and warfare dating back more than two thousand years. Perhaps the most interesting section of the boundary is that to the west of Stourbridge which currently separates Dudley Metropolitan Borough from Kinver in Staffordshire. This has been the county boundary for a millennium, and its course mirrors the outline of the medieval manors of Oldswinford and Pedmore; the Domesday hundred of Clent; Anglo-Saxon royal estates, the Norman forest of Kinver and perhaps the 7th-9th century Hwiccan kingdom as well as post-Roman tribal territories. The boundary may even have its roots in earlier (though probably more diffuse) frontiers dating back to prehistoric times. Extent and Description As shown in figure 1, the boundary begins at the southern end of County Lane near its junction with the ancient road (now just a rough public footpath) joining Iverley to Ounty John Lane. It follows County Lane north-north-west, crosses the A451 and then follows the line of Sandy Lane (now a bridleway) to the junction of Sugar Loaf Lane and The Broadway. Along with County Lane, this section of Sandy Lane lies upon a first-century Roman road that connected Droitwich (Salinae) to the Roman encampments at Greensforge near Ashwood. Past Sugar Loaf Lane, the line of the boundary diverges by a few degrees to the east of the Roman road, which continues on in a straight line under the fields of Staffordshire towards Newtown Bridge and Prestwood. -

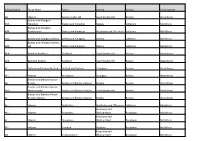

Polling District Parish Ward Parish District County Constitucency

Polling District Parish Ward Parish District County Constitucency AA - <None> Ashton-Under-Hill South Bredon Hill Bredon West Worcs Badsey and Aldington ABA - Aldington Badsey and Aldington Badsey Littletons Mid Worcs Badsey and Aldington ABB - Blackminster Badsey and Aldington Bretforton and Offenham Littletons Mid Worcs ABC - Badsey and Aldington Badsey Badsey and Aldington Badsey Littletons Mid Worcs Badsey and Aldington Bowers ABD - Hill Badsey and Aldington Badsey Littletons Mid Worcs ACA - Beckford Beckford Beckford South Bredon Hill Bredon West Worcs ACB - Beckford Grafton Beckford South Bredon Hill Bredon West Worcs AE - Defford and Besford Besford Defford and Besford Eckington Bredon West Worcs AF - <None> Birlingham Eckington Bredon West Worcs Bredon and Bredons Norton AH - Bredon Bredon and Bredons Norton Bredon Bredon West Worcs Bredon and Bredons Norton AHA - Westmancote Bredon and Bredons Norton South Bredon Hill Bredon West Worcs Bredon and Bredons Norton AI - Bredons Norton Bredon and Bredons Norton Bredon Bredon West Worcs AJ - <None> Bretforton Bretforton and Offenham Littletons Mid Worcs Broadway and AK - <None> Broadway Wickhamford Broadway Mid Worcs Broadway and AL - <None> Broadway Wickhamford Broadway Mid Worcs AP - <None> Charlton Fladbury Broadway Mid Worcs Broadway and AQ - <None> Childswickham Wickhamford Broadway Mid Worcs Honeybourne and ARA - <None> Bickmarsh Pebworth Littletons Mid Worcs ARB - <None> Cleeve Prior The Littletons Littletons Mid Worcs Elmley Castle and AS - <None> Great Comberton Somerville -

Including CIL Neighbourhood Planning Process SWDP Policy

Contents Introduction 1 Introduction 1 Local Development Scheme - including CIL 2 Local Development Schemes 1 3 South Worcestershire Development Plan Review Progress 2 Neighbourhood Planning Process 4 Neighbourhood Plans 3 SWDP Policy Monitoring 5 Strategic Policies 7 6 Economic Growth 18 7 Housing 25 8 Environmental Enhancements 30 9 Resource Management 33 10 Tourism and Leisure 37 Allocation Policies 11 SWDP 43 to SWDP 59: Allocation Policies 39 Implementation and Monitoring 12 SWDP 62 Implementation 40 13 SWDP 63: Monitoring Framework 40 Community Infrastructure Levy and Developer Contributions Monitoring 14 Community Infrastructure Levy (CIL) 41 Contents 15 Developer Contributions 41 Appendices 16 Appendix 1: Housing Statistics 43 17 Appendix 2: Employment Land Statistics 55 18 Appendix 3: Retail Land Statistics 56 19 Appendix 4: SWDP Allocations Progress 57 20 Appendix 5: Housing Trajectories updated to 31st March 2019 74 21 Appendix 6: South Worcestershire Location Diagram 81 AMR 2019 1 Introduction This Authorities Monitoring Report (AMR) has been jointly prepared by Malvern Hills District Council, Worcester City Council and Wychavon District Council who for the purposes of plan making are referred to as the South Worcestershire Councils (SWC).The area covered by the three Councils is shown in the diagram at Appendix 6. The report monitors the policies of the South Worcestershire Development Plan (SWDP) which was adopted on 25th February 2016. It also monitors progress on associated Development Plan Documents. The report provides updates regarding Neighbourhood Plan preparation across the South Worcestershire area, inclusive of any cross boundary working. This report covers the period 1st April 2018 to 31st March 2019. -

Abbots Morton Walk

Abbots Morton lies about 9 miles to the north of past ‘The Old Vicarage’ on the left, where King Charles Evesham, approached from the A441 Redditch road, I is repu ted to have stayed and inadvertently left a which is off the A435 (T) Evesham to Alcester road. book of military maps, en route to Naseby in 1645. Alternatively, it can be reached from the A422 Worcester to Alcester road via Flyford Flavell and A complete restoration of the church, which dates back Radford. to the 14 th century, was carried out in 1887. The north face is interestingly adorned with battlements an d Abbots Morton is a village which still has a late pinnacles, and grotesque gargoyles stare down from medieval look about it. Prior to 1803, when the the parapet of the ornate porch. St Peter’s stands high remainder of the common land was enclosed, all the on a bank overlooking the countryside, and seats have farms were in the village and all the villagers had some been strategically placed, on the east side of the neat stake, however small, in the large, open, hedge less churchyard, to take full advantage of this beautiful fields. The Act which enclosed the open fields setting. stipulated that each landowner had to hedge his land. This was too expensive an undertaking for the small From the church go down the lane with care. Opposite cottager who had to sell-out to the larger farmer. The the drive on the right there is a path in the woods to an result was a number of large units, s oon to have their overgrown, complete moated site. -

8.4 Sheduled Weekly List of Decisions Made

LIST OF DECISIONS MADE FOR 08/06/2020 to 12/06/2020 Listed by Ward, then Parish, Then Application number order Application No: 20/00725/FUL Location: Bretforton Community Social Club, 60 Main Street, Bretforton, Evesham, WR11 7JH Proposal: Enlargement of existing shop to include shop store and disabled WC. Full planning approval for enlarged shop in place of temporary planning approval and re-roofing of the building with reconstructed Welsh slate. Decision Date: 09/06/2020 Decision: Approval Applicant: Mrs. Andrea Evans Agent: Mr. Robert Davis Tygwyn 6 Station Road Church Street Bretforton Offenham EVESHAM Evesham WR117HX WR118RW Parish: Bretforton Ward: Bretforton and Offenham Ward Case Officer: Gillian McDermott Expiry Date: 22/06/2020 Case Officer Phone: 01684 862445 Case Officer Email: [email protected] Click On Link to View the Decision Notice: Click Here Application No: 20/00662/ADV Location: Budgens Store, 16 Russell Square, High Street, Broadway, WR12 7AP Proposal: 4 Graphic Panels to trolley bay (non-illuminated) Decision Date: 10/06/2020 Decision: Approval Applicant: Julian James Agent: Martin Millington Co-operative House Hillwood House Warwick Tech Park Hopwas Hill Gallows Hill Lichfield Road Warwick Hopwas CV34 6DA Staffs B78 3AN Parish: Broadway Ward: Broadway and Wickhamford Ward Case Officer: Robert Smith Expiry Date: 03/06/2020 Case Officer Phone: 01684 862410 Case Officer Email: [email protected] Click On Link to View the Decision Notice: Click Here Page 1 of 7 Application No: 20/00688/FUL Location: The Bakehouse, Back Lane, Broadway, WR12 7BP Proposal: Partial removal of East facing gable & rebuilding to match original. -

8.4 Sheduled Weekly List of Decisions Made

LIST OF DECISIONS MADE FOR 05/07/2021 to 09/07/2021 Listed by Ward, then Parish, Then Application number order Application No: 21/00633/LB Location: The Hay Loft, Northwick Hotel, Waterside, Evesham, WR11 1BT Proposal: Refurbishment of existing rooms including the addition of mezzanine floors and removal of modern ceiling to reveal full height of bay windows. Original lathe and plaster ceiling to be retained. Decision Date: 08/07/2021 Decision: Approval Applicant: Envisage Complete Interiors Agent: Envisage Complete Interiors Flax Furrow Flax Furrow The Old Brickyard The Old Brickyard Kiln Lane Kiln Lane Stratford-upon-avon Stratford-upon-avon CV3T 0ED CV3T 0ED Parish: Evesham Ward: Bengeworth Ward Case Officer: Craig Tebbutt Expiry Date: 12/07/2021 Case Officer Phone: 01386 565323 Case Officer Email: [email protected] Click On Link to View the Decision Notice: Click Here Application No: 21/00565/TPOA Location: The Grange, Stoney Lane, Earls Common, Himbleton, Droitwich Spa, WR9 7LD Proposal: T1 - Yew to front of property - Carefully reduce crown by 30% removing dead wood and crossing, rubbing branches. Reason: due to location of the tree the roots are causing damage to drive Decision Date: 09/07/2021 Decision: Approval Applicant: Mr A Summerwill Agent: K W Boulton Tree Care Specialists LTD The Grange The Park Stoney Lane Wyre Hill Earls Common Pershore Himbleton WR10 2HT WR9 7LD Parish: Himbleton Ward: Bowbrook Ward Case Officer: Sally Griffiths Expiry Date: 28/04/2021 Case Officer Phone: 01386 565308 Case Officer Email: -

Mondays to Fridays Saturdays Sundays

192 Halesowen - Hagley - Kidderminster Diamond Bus The information on this timetable is expected to be valid until at least 19th October 2021. Where we know of variations, before or after this date, then we show these at the top of each affected column in the table. Direction of stops: where shown (eg: W-bound) this is the compass direction towards which the bus is pointing when it stops Mondays to Fridays Halesowen, Halesowen Bus Station (Stand E) 0735 0920 20 1520 1630 1730 1830 § Halesowen, Blackberry Lane (Adjacent 1) 0736 0921 21 1521 1631 1731 1831 § Hasbury, School Lane (Adjacent 2) 0737 0922 22 1522 1632 1732 1832 § Hasbury, Albert Road (Opposite 2) 0738 0923 23 1523 1633 1733 1833 § Hasbury, Uffmoor Lane (Adjacent 2) 0739 0924 24 1524 1634 1734 1834 § Hayley Green, nr Cherry Tree Lane 0740 0925 25 1525 1635 1735 1835 § Hayley Green, adj Waugh Drive 0741 0926 26 1526 1636 1736 1836 § Hayley Green, opp Lutley Lane 0742 0927 27 1527 1637 1737 1837 Hagley, adj Hagley Golf Course 0745 0930 30 1530 1640 1740 1840 § Hagley, opp Wassell Grove Road 0745 0930 30 1530 1640 1740 1840 § Hagley, adj School Lane 0746 0931 31 1531 1641 1741 1841 § Hagley, adj Paramount Showrooms 0746 0931 31 1531 1641 1741 1841 § Hagley, adj Hagley Primary School 0746 0931 31 1531 1641 1741 1841 § Hagley, Station Road (W-bound) 0747 0932 32 1532 1642 1742 1842 then § West Hagley, opp Free Church 0747 0932 32 1532 1642 1742 1842 at § West Hagley, opp Summervale Road 0747 0932 32 1532 1642 1742 1842 these § West Hagley, Newfield Road (S-bound) 0747 0932 32 1532 -

Evesham, Bredon, Broadway & Inkberrow Population

EVESHAM, BREDON, BROADWAY & INKBERROW POPULATION PROFILE Purpose The locality profiles have been produced to – Support shared understanding of the health and care needs and experiences of local people accessing services Provide insights into how people are currently using health services and their outcomes Help to identify opportunities for collaborative working within and across localities These profiles have not been produced for the purposes of performance management. They are intended to support Neighbourhood Team in identifying their priorities for the forthcoming year. Although some of the data might be familiar to you, it is hoped that you will be able to gain a greater insight into the challenges facing the local population when viewing this in the context of a wider data set. This is the first attempt at compiling this data at Neighbourhood Team level. We would expect that as teams have had the opportunity to use this information, we may need to refine the data set over the initial period. If this data proves useful, we will refresh and refine the profiles on an annual basis. It only provides a snapshot across a broad range of indicators, but in producing this, we have compiled a comprehensive data set which we can drill down into as requested. Neighbourhood teams will also be provided with a monthly dashboard of indicators which will demonstrate the performance of their integrated community team. Once the Neighbourhood Teams have identified their priorities for the year, we will provide support in developing a monthly dataset to help you to monitor the effectiveness of any new developments you put in place. -

564 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

564 bus time schedule & line map 564 Pershore - Inkberrow - Evesham - Pershore View In Website Mode The 564 bus line (Pershore - Inkberrow - Evesham - Pershore) has 3 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Evesham: 8:06 AM - 10:05 AM (2) Inkberrow: 5:50 PM (3) Pershore: 8:00 AM - 1:35 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 564 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 564 bus arriving. Direction: Evesham 564 bus Time Schedule 40 stops Evesham Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday Not Operational Monday 8:06 AM - 10:05 AM Abbey Tea Rooms, Pershore 29 Broad Street, Pershore Civil Parish Tuesday 8:06 AM - 10:05 AM Head Street, Pershore Wednesday 8:06 AM - 10:05 AM 150B High Street, Pershore Thursday 8:06 AM - 10:05 AM Whitcroft Road, Pershore Friday 8:06 AM - 10:05 AM Hurst Park, Pershore Saturday 10:05 AM Pershore High School, Pershore Pershore Railway Station, Pershore A4104, Pershore Civil Parish 564 bus Info Direction: Evesham Crossroads, Pinvin Stops: 40 Trip Duration: 64 min Coach & Horses, Pinvin Line Summary: Abbey Tea Rooms, Pershore, Head Main Street, Pinvin Civil Parish Street, Pershore, Whitcroft Road, Pershore, Hurst Park, Pershore, Pershore High School, Pershore, Main Street, Pinvin Pershore Railway Station, Pershore, Crossroads, Checketts Close, Pinvin Civil Parish Pinvin, Coach & Horses, Pinvin, Main Street, Pinvin, Tilesford Park, Throckmorton, Airƒeld Entrance, Tilesford Park, Throckmorton Throckmorton, Village Hall, Throckmorton, The Close, Throckmorton, Moat Farm Lane, Bishampton, -

8.4 Sheduled Weekly List of Decisions Made

LIST OF DECISIONS MADE FOR 13/04/2020 to 17/04/2020 Listed by Ward, then Parish, Then Application number order Application No: 20/00481/HP Location: 51 Deacle Place, Evesham, WR11 3DD Proposal: Two storey side/rear extensions and single storey rear extension. Decision Date: 15/04/2020 Decision: Approval Applicant: Mrs A Chadzynska Agent: Mr Rod Navarrete 51 Deacle Place 27b High Street Evesham Highworth WR11 3DD Swindon SN6 7AG Parish: Evesham Ward: Bengeworth Ward Case Officer: Hazel Smith Expiry Date: 07/05/2020 Case Officer Phone: 01386 565318 Case Officer Email: [email protected] Click On Link to View the Decision Notice: Click Here Application No: 20/00496/LB Location: 36 Bridge Street, Evesham, WR11 4RR Proposal: Alterations to facilitate change of use of existing building to residential retaining existing retail shop at ground level. Decision Date: 15/04/2020 Decision: Approval Applicant: Mr R Sharples Agent: Mr F Scimeca Mouse Court Twyford Lodge Lower End Blayney's Lane Bricklehampton Evesham Pershore Worcs Worcs WR11 4TR WR10 3HL Parish: Evesham Ward: Bengeworth Ward Case Officer: Oliver Hughes Expiry Date: 30/04/2020 Case Officer Phone: 01386 565191 Case Officer Email: [email protected] Click On Link to View the Decision Notice: Click Here Page 1 of 12 Application No: 20/00531/HP Location: 103 Badsey Lane, Evesham, WR11 3EY Proposal: Rebuild and extend existing ground floor extension and demolish garage Decision Date: 17/04/2020 Decision: Approval Applicant: Mrs R Bell Agent: Mr Trevor Roberts -

South Worcestershire Development Plan (SWDP) and Good Practice on Designing Gypsy and Traveller Sites

South Worcestershire Traveller and Travelling Showpeople Site Allocations Development Plan Document Revised Site Assessment Background Report February 2018 Page 1 of 30 Background The Government’s Planning Policy for Traveller Sites (August 2015) states that local planning authorities should, in producing their Local Plan “identify and update annually, a supply of specific deliverable sites sufficient to provide five years’ worth of sites against their locally set targets”. Further, Local Plans should “identify a supply of specific, developable sites or broad locations for growth, for years six to ten and, where possible, for years 11-15”. Planning Policy for Traveller Sites says that to be deliverable, sites should: Be available now, Offer a suitable location for development now, and Be achievable with a realistic prospect that housing will be delivered on the site within five years and in particular that development on the site is viable. To be considered developable, sites should be in a suitable location for Traveller site development and there should be a reasonable prospect that the site is available and could be viably developed at the point envisaged. Planning Policy for Traveller Sites also says that “criteria should be set to guide land supply allocations where there is identified need. Where there is no identified need, criteria-based policies should be included to provide a basis for decisions in case applications nevertheless come forward. Criteria based policies should be fair and should facilitate the traditional and nomadic life of travellers while respecting the interests of the settled community”. Purpose The purpose of this document is to set out the methodology for assessing the broad suitability of potential sites for Travellers and Travelling Showpeople to inform proposed allocations in the South Worcestershire Traveller and Travelling Showpeople Site Allocations Development Plan Document.