THE IMPACT of the EPIDEMICS of 1727-1730 in SOUTH WEST WORCESTERSHIRE by J

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Parentage of Anne Henzey

The Parentage of Anne Henzey On July 1st, 1675 “Mr Samuel Ward, Rector of Strensham & Mrs Anne Henzey of Amblecoat in ye parish of Oldswinford” were married at Pedmore, Worcestershire. Their Marriage Allegation, dated 23 Jun 1675, gives further information: “Mr Samuel Warde Rector of Strensham ... aged 34 years or thereabouts a Batchelor ...[and] Anne Henzey of the parish of Oldswinford ... aged 20 years or thereabouts and a maiden their parents livinge on both sides and to the intended marriage consenting ...” Samuel and Anne Ward had three children, two daughters, Ann and Elizabeth, baptised in 1676 and 1678, and one son, Paul, baptised and buried in 1680. Family naming patterns suggest that Ann would be the name of the wife’s mother, or less commonly that of the husband’s mother, and that Paul would be the name of the husband’s father, or less commonly that of the wife’s father, particularly if the wife’s father was wealthy. The only one of these names to appear in Samuel Ward’s family before 1680 was Elizabeth, which was the name of his sister-in-law and niece. Samuel’s parents, both of whom were living in Coventry in 1675, were named Samuel and Joan. 1 It can therefore be established that Anne Henzey was probably born between June 1654 and June 1655, that she came from Amblecoat in the parish of Oldswinford, Worcestershire, and that both her parents were living in 1675. It is also probable that the names Paul and Anne appeared in the family, possibly as Anne’s parents. -

The Parish Magazine Takes No Responsibility for Goods Or Services Advertised

Ashton-under-Hill The Beckford Overbury Parish Alstone & Magazine Teddington July 2018 50p Quiet please! Kindly don’t impede my concentration I am sitting in the garden thinking thoughts of propagation Of sowing and of nurturing the fruits my work will bear And the place won’t know what’s hit it Once I get up from my chair. Oh, the mower I will cherish, and the tools I will oil The dark, nutritious compost I will stroke into the soil My sacrifice, devotion and heroic aftercare Will leave you green with envy Once I get up from my chair. Oh the branches I will layer and the cuttings I will take Let other fellows dig a pond, I shall dig a LAKE My garden – what a showpiece! There’ll be pilgrims come to stare And I’ll bow and take the credit Once I get up from my chair. Extracts from ‘When I get Up From My Chair’ by Pam Ayres Schedule of Services for The Parish of Overbury with Teddington, Alstone and Little Washbourne, with Beckford and Ashton under Hill. JULY Ashton Beckford Overbury Alstone Teddington 6.00 pm 11.00 am 1st July 8:00am 9.30 am Evening Family 5th Sunday BCP HC CW HC Prayer Service after Trinity C Parr Clive Parr S Renshaw Lay Team 6.00 pm 11.00 am 9.30 am 8th July 9.30 am Evening Morning Morning 6th Sunday CW HC Worship Prayer Prayer after Trinity S Renshaw R Tett S Renshaw Roger Palmer 11.00 am 6.00 pm 15th July 9.30 am 8.00 am Village Evening 7th Sunday CW HC BCP HC Worship Prayer after Trinity M Baynes M Baynes G Pharo S Renshaw 10.00 am United Parish 22nd July CW HC 8th Sunday & Alstone after Trinity Patronal R Tett 29th July 10:30am 9th Sunday Bredon Hill Group United Worship after Trinity Overbury AUGUST 6.00 pm 5th August 8.00 am 9.30 am Evening 10th Sunday BCP HC CW HC Prayer after Trinity S Renshaw S Renshaw S Renshaw Morning Prayers will be said at 8.30am on Fridays at Ashton. -

A Cornerstone of the Historical Landscape

Stourbridge's Western Boundary: A cornerstone of the historical landscape by K James BSc(Hons) MSc PhD FIAP (email: [email protected]) The present-day administrative boundaries around Stourbridge are the result of a long and complex series of organizational changes, land transfers and periods of settlement, invasion and warfare dating back more than two thousand years. Perhaps the most interesting section of the boundary is that to the west of Stourbridge which currently separates Dudley Metropolitan Borough from Kinver in Staffordshire. This has been the county boundary for a millennium, and its course mirrors the outline of the medieval manors of Oldswinford and Pedmore; the Domesday hundred of Clent; Anglo-Saxon royal estates, the Norman forest of Kinver and perhaps the 7th-9th century Hwiccan kingdom as well as post-Roman tribal territories. The boundary may even have its roots in earlier (though probably more diffuse) frontiers dating back to prehistoric times. Extent and Description As shown in figure 1, the boundary begins at the southern end of County Lane near its junction with the ancient road (now just a rough public footpath) joining Iverley to Ounty John Lane. It follows County Lane north-north-west, crosses the A451 and then follows the line of Sandy Lane (now a bridleway) to the junction of Sugar Loaf Lane and The Broadway. Along with County Lane, this section of Sandy Lane lies upon a first-century Roman road that connected Droitwich (Salinae) to the Roman encampments at Greensforge near Ashwood. Past Sugar Loaf Lane, the line of the boundary diverges by a few degrees to the east of the Roman road, which continues on in a straight line under the fields of Staffordshire towards Newtown Bridge and Prestwood. -

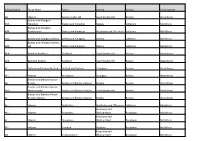

Polling District Parish Ward Parish District County Constitucency

Polling District Parish Ward Parish District County Constitucency AA - <None> Ashton-Under-Hill South Bredon Hill Bredon West Worcs Badsey and Aldington ABA - Aldington Badsey and Aldington Badsey Littletons Mid Worcs Badsey and Aldington ABB - Blackminster Badsey and Aldington Bretforton and Offenham Littletons Mid Worcs ABC - Badsey and Aldington Badsey Badsey and Aldington Badsey Littletons Mid Worcs Badsey and Aldington Bowers ABD - Hill Badsey and Aldington Badsey Littletons Mid Worcs ACA - Beckford Beckford Beckford South Bredon Hill Bredon West Worcs ACB - Beckford Grafton Beckford South Bredon Hill Bredon West Worcs AE - Defford and Besford Besford Defford and Besford Eckington Bredon West Worcs AF - <None> Birlingham Eckington Bredon West Worcs Bredon and Bredons Norton AH - Bredon Bredon and Bredons Norton Bredon Bredon West Worcs Bredon and Bredons Norton AHA - Westmancote Bredon and Bredons Norton South Bredon Hill Bredon West Worcs Bredon and Bredons Norton AI - Bredons Norton Bredon and Bredons Norton Bredon Bredon West Worcs AJ - <None> Bretforton Bretforton and Offenham Littletons Mid Worcs Broadway and AK - <None> Broadway Wickhamford Broadway Mid Worcs Broadway and AL - <None> Broadway Wickhamford Broadway Mid Worcs AP - <None> Charlton Fladbury Broadway Mid Worcs Broadway and AQ - <None> Childswickham Wickhamford Broadway Mid Worcs Honeybourne and ARA - <None> Bickmarsh Pebworth Littletons Mid Worcs ARB - <None> Cleeve Prior The Littletons Littletons Mid Worcs Elmley Castle and AS - <None> Great Comberton Somerville -

8.4 Sheduled Weekly List of Decisions Made

LIST OF DECISIONS MADE FOR 02/08/2021 to 06/08/2021 Listed by Ward, then Parish, Then Application number order Application No: 21/01521/TPOA Location: Land at (OS 0531 4439),, Lodge Park Drive,, Evesham Proposal: 1 no. Maple tree located in open space on Lodge Park Drive - selectively reduce the crown by 20/25%. Reason: for maintenance and safety Decision Date: 03/08/2021 Decision: Approval Applicant: Agent: Mrs Emma Tassi Verdure Land Management PO Box 19860 Nottingham NG13 9UX Parish: Aldington Ward: Badsey Ward Case Officer: Sally Griffiths Expiry Date: 12/08/2021 Case Officer Phone: 01386 565308 Case Officer Email: [email protected] Click On Link to View the Decision Notice: Click Here Application No: 21/01496/CLPU Location: 2 Badsey Fields Lane, Badsey, Evesham, WR11 7EX Proposal: Application for a Lawful development certificate for the construction of a covered link between the existing house and the existing single garage Decision Date: 06/08/2021 Decision: Certified Applicant: Mr & Mrs A Richards Agent: Grahame Aldington 2, Badsey Fields Lane Blenheim Badsey Main Street WR11 7EX South Littleton WR11 8TJ Parish: Badsey Ward: Badsey Ward Case Officer: Hazel Smith Expiry Date: 10/08/2021 Case Officer Phone: 01684 862342 Case Officer Email: [email protected] Click On Link to View the Decision Notice: Click Here Page 1 of 19 Application No: 21/01885/NMA Location: 12 Market Place, Evesham, WR11 4RW Proposal: Non-material amendment to application 21/01342/FUL for change of use from a Betting Shop (Use Class Sui Generis) to a pizza takeaway and delivery operation (Use Class Sui Generis) including associated external alterations. -

Choice Plus:Layout 1 5/1/10 10:26 Page 3 Home HOME Choice CHOICE .ORG.UK Plus PLUS

home choice plus:Layout 1 5/1/10 10:26 Page 3 Home HOME Choice CHOICE .ORG.UK Plus PLUS ‘Working in partnership to offer choice from a range of housing options for people in housing need’ home choice plus:Layout 1 5/1/10 10:26 Page 4 The Home Choice Plus process The Home Choice Plus process 2 What is a ‘bid’? 8 Registering with Home Choice plus 3 How do I bid? 9 How does the banding system work? 4 How will I know if I am successful? 10 How do I find available properties? 7 Contacts 11 What is Home Choice Plus? Home Choice Plus has been designed to improve access to affordable housing. The advantage is that you only register once and the scheme allows you to view and bid on available properties for which you are eligible across all of the districts. Home Choice Plus has been developed by a number of Local Authorities and Housing Associations working in partnership. Home Choice Plus is a way of allocating housing and advertising other housing options across the participating Local Authority areas. (Home Choice Plus will also be used for advertising other housing options such as private rents and intermediate rents). This booklet explains how to look for housing across all of the Districts involved in this scheme. Please see website for further information. Who is eligible to join the Home Choice Plus register? • Some people travelling to the United Kingdom are not entitled to Housing Association accommodation on the basis of their immigration status. • You may be excluded if you have a history of serious rent arrears or anti social behaviour. -

Church End Hanley Castle Worcester WR8 0BL

RESIDENTIAL BUILDING PLOT Church End Hanley Castle Worcester WR8 0BL Accommodation comprising: Ground Floor: Entrance Hall, Living Room, Kitchen/Diner, Bedroom and Shower Room. First Floor: Two Bedrooms and Family Bathroom. Outside: Cottage garden, external parking and detached Garage with covered Log Store. GUIDE PRICE: £110,000 Situation The residential building plot is situated within the attractive Church End Conservation area and presently forms part of the garden to a half-timbered Grade II Listed property known as 27 Church End. The Approved plans for the building plot provide direct road frontage to Church End. The Village of Hanley Castle benefits from a Secondary School and a traditional Public House. Further services are available at Hanley Swan and Upton upon Severn. Hanley Castle is well placed for access to the surrounding commercial centres of Upton upon Severn, Malvern, Tewkesbury, Worcester, Cheltenham and Birmingham. Description The approved plans permit the construction of a cottage style dwelling which respects the building plots setting within the village conservation area. Overall the gross external area of the property, according to the Architects plans, extends to 96 sq m/1033.sq ft. The approved plans also provide for a cottage garden together with a gravelled driveway, parking area and a single garage. The design of the property itself provides for sustainable long-term occupancy with bedrooms and bathrooms at both ground and first floor levels. Planning Permission Planning Permission was granted upon appeal on 23rd February 2011 following refusal to grant planning by Malvern Hills District Council. A copy of the Inspectors appeal decision is attached to these particulars. -

BONNERS COTTAGE QUAY LANE HANLEY CASTLE WORCESTERSHIRE Pughs

BONNERS COTTAGE QUAY LANE HANLEY CASTLE WORCESTERSHIRE Pughs WR8 0BS BONNERS COTTAGE Pughs QUAY LANE ESTAT E AGENTS & VALUERS HANLEY CASTLE Hazle Meadows Auction Centre, Ross Road, Ledbury, HR8 2LP WORCESTERSHIRE Tel: (01531) 631122 Fax: 631818 Email: [email protected] WR8 0BS Website: www.hjpugh.co.uk Bonners Cottage is an artist's dream. In a rural tranquil location on the outskirts of Upton upon Severn with a well maintained garden. This four bedroom detached Grade II Listed cottage has huge potential to improve. Due to its close proximity to the River Severn it has flooded in recent years. VIEWING HIGHLY RECOMMENDED AUCTION GUIDE PRICE £250,000 - £300,000 Vendors Solicitors: Star Legal, Sterling Lodge, 287 Worcester Road, Malvern, WR14 1AB. Hilary Evans acting. Tel 01684 562 526 To be offered for sale by public auction live and online, subject to conditions of sale and unless previously sold at The Hazle Meadows Auction Centre, Ross Road, HR8 2LP on Wednesday 28th July 2021 at 6:30pm Partners: H J Pugh FNAEA FNAVA; J H Pugh BSc (Hons) MRICS MNAVA; J D Thomson BSc (Hons) MRICS FAAV MARLA BONNERS COTTAGE, QUAY LANE, HANLEY CASTLE, WORCESTERSHIRE, WR8 0BS ENTRANCE LANDING AUCTION GUIDE PRICE Timber door to Access to loft, exposed timbers and beams £250,000 - £300,000 Please note an Auction Guide Price is an indication by ENTRANCE PORCH BEDROOM THREE 4.8m x 3.1m the Agent of the likely sale price and is not the same as Timber stable door to Exposed timbers and beams, timber door to balcony, a Reserve Price. -

Worcestershire Roads and Roadworks Report

Worcestershire Roads and Roadworks Report 26/08/2019 - 08/09/2019 Works impact : High Lower Event impact : High Lower Traffic Traffic Light Road No. Expected Expected District Location Street Name Town / Locality Works Promoter Work / Event Description Management Manual Control TMA Ref (A & B Only) Start Finish Type Requirements The Junction With Rowney Green Lane (C2034) To The Worcestershire JZ101214593 Bromsgrove Radford Road Alvechurch 26/08/2019 06/09/2019 Carriageway Patching Road Closure Junction With Watery Lane (C2042) Highways JZ101214602 The Junction Of U22011 Fish House Lane To A Distance Of Worcestershire Bromsgrove Approx 210.84 Meters In A South Easterly Direction Along Sugarbrook Lane Stoke Pound 26/08/2019 30/08/2019 Drainage Work / Flood Alleviation Road Closure JZ101214046 Highways U22012 Sugarbrook Lane From The Junction Of C2062 Dordale Road To Approx 874.00 BC005CC8W00DIGWAKV Bromsgrove Meters In A Northerly Direction Along U20216 Hockley Brook Woodcote Lane Dodford BT Openreach 27/08/2019 29/08/2019 New Customer Connection Road Closure FE1WA1 Lane The Junction Of Alcester Road (A435) To The Junction Of Worcestershire Bromsgrove Billesley Lane Portway 27/08/2019 06/09/2019 Carriageway Patching Road Closure JZ101214625 Lilley Green Road (C2044) Highways The Junction Of C2058 Whettybridge Road To Approx 405.00 Western Power Bromsgrove Meters In A South Westerly Direction Along U21425 Holywell Holywell Lane Rubery 28/08/2019 28/08/2019 Overhead Works Road Closure DY715M41152127881 Distribution Lane Junction With U20216 -

Dudley Metropolitan Borough Council Polling Station List

Dudley Metropolitan Borough Council Polling Station List European Parliamentary Election Thursday 23 May 2019 Reference Address Districts 1 Foxyards Primary School, Foxyards Road, Tipton, West Midlands, A01 DY4 8BH 2 Caravan, Forest Road, Dudley, West Midlands, DY1 4BX A02 3 Sea Cadet H Q, Tipton Road, Dudley, West Midlands, DY1 4SQ A03 4 Ward Room, Priory Hall, Training Centre, Dudley, West Midlands, A04 DY1 4EU 5 Priory Primary School, Entrance In Cedar Road and Limes Road, A05 Dudley, West Midlands, DY1 4AQ 6 Reception Block Bishop Milner R C School, (Car Access The A06 Broadway), Burton Road, Dudley, West Midlands, DY1 3BY 7 Midlands Co-Op, Dibdale Road West, Milking Bank, Dudley, DY1 A07 2RH 8 Sycamore Green Centre, Sycamore Green, Dudley, West Midlands, A08,G04 DY1 3QE 9 Wrens Nest Primary School, Marigold Crescent, Dudley, West A09 Midlands, DY1 3NQ 10 Priory Community Centre, Priory Road, Dudley, West Midlands, DY1 A10 4ED 11 Rainbow Community Centre, 49 Rainbow Street, Coseley, West B01 Midlands, WV14 8SX 12 Summerhill Community Centre, 28B Summerhill Road, Coseley, B02 West Midlands, WV14 8RD 13 Wallbrook Primary School, Bradleys Lane, Coseley, West Midlands, B03 WV14 8YP 14 Coseley Youth Centre, Clayton Park, Old Meeting Road, Coseley, B04 WV14 8HB 15 Foundation Years Unit, Christ Church Primary School, Church Road, B05 Coseley, WV14 8YB 16 Roseville Methodist Church Hall, Bayer Street, Coseley, West B06 Midlands, WV14 9DS 17 Activity Centre, Silver Jubilee Park, Mason Street, Coseley, WV14 B07 9SZ 18 Hurst Hill Primary School, -

Lime Kilns in Worcestershire

Lime Kilns in Worcestershire Nils Wilkes Acknowledgements I first began this project in September 2012 having noticed a number of limekilns annotated on the Ordnance Survey County Series First Edition maps whilst carrying out another project for the Historic Environment Record department (HER). That there had been limekilns right across Worcestershire was not something I was aware of, particularly as the county is not regarded to be a limestone region. When I came to look for books or documents relating specifically to limeburning in Worcestershire, there were none, and this intrigued me. So, in short, this document is the result of my endeavours to gather together both documentary and physical evidence of a long forgotten industry in Worcestershire. In the course of this research I have received the help of many kind people. Firstly I wish to thank staff at the Historic Environmental Record department of the Archive and Archaeological Service for their patience and assistance in helping me develop the Limekiln Database, in particular Emma Hancox, Maggi Noke and Olly Russell. I am extremely grateful to Francesca Llewellyn for her information on Stourport and Astley; Simon Wilkinson for notes on Upton-upon-Severn; Gordon Sawyer for his enthusiasm in locating sites in Strensham; David Viner (Canal and Rivers Trust) in accessing records at Ellesmere Port; Bill Lambert (Worcester and Birmingham Canal Trust) for involving me with the Tardebigge Limekilns Project; Pat Hughes for her knowledge of the lime trade in Worcester and Valerie Goodbury -

Malvern Hills Site Assessments August 2019 LC-503 Appendix B MH Sites 1 310519CW.Docx Appendix B: Malvern Hills Site Assessments

SA of the SWDPR: Malvern Hills Site Assessments August 2019 LC-503_Appendix_B_MH_Sites_1_310519CW.docx Appendix B: Malvern Hills Site Assessments © Lepus Consulting for Malvern Hills District Council Bi SA of the SWDPR: Malvern Hills Site Assessments August 2019 LC-503_Appendix_B_MH_Sites_1_310519CW.docx Appendix B Contents B.1 Abberley ..................................................................................................................................... B1 B.2 Astley Cross ............................................................................................................................. B8 B.3 Bayton ...................................................................................................................................... B15 B.4 Bransford ............................................................................................................................... B22 B.5 Broadwas ............................................................................................................................... B29 B.6 Callow End ............................................................................................................................ B36 B.7 Clifton upon Teme ............................................................................................................. B43 B.8 Great Witley ........................................................................................................................... B51 B.9 Hallow .....................................................................................................................................