This Is an Electronic Reprint of the Original Article. This Reprint May Differ from the Original in Pagination and Typographic Detail

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ylen Ula-Palvelut

UTSJOKI ULA-LÄHETYSTEN I 90,7 C II 93,1 C III 99,4 C NUORGAM < < VI 102,6 C KUULUVUUSALUEET TENOLA I 88,6 I 89,0 • < • II 93,9 II 94,1 III 97,7 Yleisradion ohjelmat III 95,8 • VI 101,2 < VI 100,5 < NÄÄTÄMÖ NUVVUS UTSJOKI I 87,6 I 88,1 C • • II 89,9 II 90,2 C III 97,4 III 94,4 C < VI 103,3 VI 101,7 C • KARIGASNIEMI KILPISJÄRVI < I 89,5 C I 88,0 V II 93,4 C II 90,9 V • III 96,8 C INARI III 96,0 V VI 100,8 C < VI 103,7 V < LAMMASKOSKI • INARI • I 88,5 C I 88,4 II 91,4 C II 92,8 III 98,7 C ENONTEKIÖ III 98,8 VI 101,2 C < VI 101,9 KUTTANEN • I 94,1 C II 97,2 C III 99,6 C VUOTSO VI 102,2 C < I 87,8 • II 90,1 III 94,3 KITTILÄ VI 101,3 MUONIO SAVUKOSKI YLLÄS SODANKYLÄ < I 92,2 C II 95,3 C • III 98,1 C VI 103,8 C KOLARI PELKOSENNIEMI < • PYHÄTUNTURI Merkkien selitykset: PELLO < I 91,0 C I 90,2 II 97,6 C • PELLO ROVANIEMEN MLK III 99,9 C II 97,0 SALLA I-verkko (YLE Radio 1) III 99,7 II-verkko (YleX) < AAVASAKSA • ROVANIEMI KEMIJÄRVI III-verkko (YLE Radio Suomi) < I 87,9 YLITORNIO ROVANIEMI IV-verkko (YLE Radio Extrem) II 89,8 • I 88,2 < RUKA III 94,7 II 94,0 I 90,7 < III 96,7 POSIO • II 92,8 VI 103,0 • < III 95,1 V-verkko (Radio Vega) TERVOLA TERVOLA I 88,6 • VI-verkko (YLE Sámi radio) II 92,6 RANUA III 95,6 KEMINMAA POSIO L1, L2.. -

Joukkoviestimet 2013

Kulttuuri ja viestintä 2014 Kultur och media Culture and the media Kulttuuri ja viestintä 2014 Kulttuuri Joukkoviestimet – Finnish Mass Media on artikkeleihin ja tilastoaineistoon perustuva monipuolinen katsaus Suomen joukkoviestinnän tilaan. Julkaisussa tarkastellaan joukko- viestimiä seuraavina kokonaisuuksina: joukkoviestinnän talous ja kulutus, sanomalehdet, aikakauslehdet, radio, televisio ja verkkomedia. Julkaisussa on myös kansainväli- siä vertailutietoja sisältävä luku. Jokaisesta joukkoviestin- nän sektorista on lisäksi tilastokatsausten yhteydessä tiiviit johdantoartikkelit. Joukkoviestimet 2013 Joukkoviestimet 2013 Finnish Mass Media ISSN 2242−6477 (pdf) ISBN 978−952−244−499−8 (pdf) ISSN 1455−9447 (print) ISBN 978−952−244−500−1 (print) Tuotenumero 3090 (print) 9 789522 445001 Tietopalvelu ja viestintä Kommunikation och informationstjänst Communication and Information Services Tilastokeskus Statistikcentralen Statistics Finland puh. 029 551 2220 tfn 029 551 2220 tel. +358 29 551 2220 www.tilastokeskus.fi www.stat.fi www.stat.fi Julkaisutilaukset: Beställning av publikationer: Publication orders: Edita Publishing Oy Edita Publishing Oy Edita Publishing Oy puh. 020 450 05 tfn 020 450 05 tel. +358 20 450 05 [email protected] www.editapublishing.fi www.editapublishing.fi www.editapublishing.fi Untitled-1 1 12.6.2014 13:07:39 Kulttuuri ja viestintä 2014 Kultur och media Culture and the media Joukkoviestimet 2013 Finnish Mass Media Helsinki – Helsingfors 2014 Tiedustelut – Förfrågningar – Inquiries: Tuomo Sauri Puh. 029 551 3449 Tel. +358 29 551 3449 [email protected] Kansikuva – Pärmbild – Cover photograph: Ilkka Kärkkäinen Kannen suunnittelu – Pärmplanering – Cover design: Irene Koumolou Taitto – Ombrytning – Layout: Eeva-Liisa Repo © 2014 Tilastokeskus – Statistikcentralen – Statistics Finland ISSN 2242−6477 (pdf) ISBN 978−952−244−499−8 (pdf) ISSN 1455−9447 (print) ISBN 978−952−244−500−1 (print) Taulukoissa käytetyt symbolit Key to symbols used in Tables Ei mitään ilmoitettavaa No information....... -

PI- Ja PS-Koodit

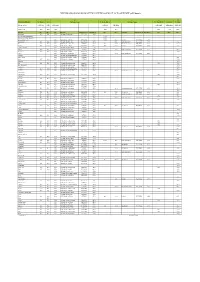

YLEISRADIO RADIOKANAVIEN LÄHETYSASEMAT JA TAAJUUDET ja PI koodit I II III IV V VI VII OHJELMAVERKKO Yle Radio 1 YleX Yle Radio Suomi Yle Radio Extrem Yle Radio Vega Yle Sámi Radio Yle Mondo Yle Puhe RDS-tunnus PS YLE YKSI YLEX YLESUOMI YLE X3M YLE VEGA YLESAAME YLEMONDO YLEPUHE RDS PI koodi 6201 6202 6203 6204 6205 6206 600A 6207 ASEMA MHz MHz MHz Alueradiot RDS-tunnus PS RDS REG PI MHz MHz Alueradiot RDS-tunnus PS RDS REG PI MHz MHz MHz Ainiovaara 87,9 89,8 94,7 Yle Radio Suomi Kemi YLE KEMI 6C03 Ahvenanmaa, Hammarland 105,2 Ahvenanmaa, Maarianhamina 104,3 Ahvenanmaa, Sund 100,3 Yle Radio Suomi Turku YLESUOMI 6203 104,9 93,1 Åboland YLE VEGA 6205 Anjalankoski 88,5 92,8 96,9 Yle Radio Suomi Kotka YLEKYMEN 6D03 99,5 Radio Östnyland YLE-VEGA 6605 91,4 Espoo 87,9 91,9 94,0 Yle Radio Suomi Helsinki YLE HKI 6403 98,9 101,1 Huvudstadsregionen YLE_VEGA 6405 97,5 103,7 Eurajoki 87,7 103,5 94,8 Yle Radio Suomi Pori YLE PORI 6803 99,4 103,0 Åboland YLE:VEGA 6705 92,0 Evijärvi, Isoneva 90,7 Yle Radio Suomi Kokkola YLE KOKK 6F03 Fiskars 90,9 93,1 97,0 Yle Radio Suomi Helsinki YLE HKI 6403 102,5 99,7 Radio Västnyland YLE,VEGA 6505 105,0 Haapavesi 89,0 96,1 98,4 Yle Radio Suomi Oulu YLE OULU 6903 101,9 Hanko 88,4 Yle Radio Suomi Helsinki YLE HKI 6403 101,9 Radio Västnyland YLE,VEGA 6505 Hausjärvi 107,8 Yle Radio Suomi Hämeenlinna YLE HML 6B03 Hämeenlinna 99,2 Yle Radio Suomi Hämeenlinna YLE HML 6B03 98,2 Iisalmi 87,7 92,8 96,5 Yle Radio Suomi Kuopio YLE KUO 6603 107,9 Ilomantsi 106,1 Inari 88,4 92,8 98,8 Yle Radio Suomi Rovaniemi YLELAPPI 6B03 101,9 -

Fifth Periodical Report Presented to the Secretary General of the Council of Europe in Accordance with Article 15 of the Charter

Strasbourg, 17 November 2017 MIN-LANG (2017) PR 7 EUROPEAN CHARTER FOR REGIONAL OR MINORITY LANGUAGES Fifth periodical report presented to the Secretary General of the Council of Europe in accordance with Article 15 of the Charter FINLAND THE FIFTH PERIODIC REPORT BY THE GOVERNMENT OF FINLAND ON THE IMPLEMENTATION OF THE EUROPEAN CHARTER FOR REGIONAL OR MINORITY LANGUAGES NOVEMBER 2017 2 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION...................................................................................................................................................6 PART I .................................................................................................................................................................7 1. BASIC INFORMATION ON FINNISH POPULATION AND LANGUAGES....................................................................7 1.1. Finnish population according to mother tongue..........................................................................................7 1.2. Administration of population data ..............................................................................................................9 2. SPECIAL STATUS OF THE ÅLAND ISLANDS.............................................................................................................9 3. NUMBER OF SPEAKERS OF REGIONAL OR MINORITY LANGUAGES IN FINLAND.................................................10 3.1. The numbers of persons speaking a regional or minority language..........................................................10 3.2. Swedish ......................................................................................................................................................10 -

Förvaltningsrådets Berättelse Till Riksdagen Om Rundradions Verksamhet 2016

Förvaltningsrådets berättelse till riksdagen om Rundradions verksamhet 2016 I enlighet med 6 § i lagen om Rundradions verksamhet lämnar bolagets förvaltningsråd en berättelse till riksdagen om hur Yles allmännyttiga verksamhet har genomförts. B 7/2017 rd En förnyelseorienterad 90-åring FÖRVALTNINGSRÅDETS ORDFÖRANDE Republikens president P.E. Svinhuf- vuds radiotal under Mäntsäläupproret, nyhetsbevakningen av mordet på John F. Kennedy, Lasse Viréns fall vid som- mar-OS i München eller biskop Eero Huovinens aftonandakt under Estoni- akatastrofen. Dessa är händelser som ristats outplånligt i finländarnas minne. Listan på motsvarande stunder som Yle förmedlat till oss kan göras hur lång som helst. Det är ingen överdrift att säga att Yle är en väsentlig del av det finländska själslandskapet. Yle fortsätter att förmedla, om och för finländarna, från när och fjärran – på En parlamentarisk arbetsgrupp med traditionella och bekanta kanaler, men riksdagsledamot Arto Satonen som ord- också med utnyttjande av den senaste förande var verksam under våren 2016. tekniken. Ett public service-rundradio- Arbetsgruppen skulle utreda omfatt- bolag verkar i sin samtid, och avspeglar ningen av Yles public service-uppdrag, och avbildar dess mångahanda fenomen sättet på vilket uppdraget uppfylls och och händelser. Till hörnstenarna för Yles finansieringsnivån, utvärdera Yles ställ- verksamhet hör relevans, trovärdighet ning och betydelse på den finländska och sanningsenlighet. Utan dem vore mediemarknaden samt bedöma bolagets det omöjligt att bygga upp en levande betydelse för demokrati, yttrandefrihet och samverkande publikrelation. och oberoende kommunikation. Arbets- Samtidigt måste bolaget vara lyhört gruppen skulle också utvärdera riksda- och proaktivt. Framtiden går inte att gens ägarstyrning av Rundradion. kontrollera, men det går att förbe- Efter lite startproblem framskred reda och gardera sig inför den. -

Yleisradion Hallinto- Neuvoston Kertomus Eduskunnalle Yhtiön Toiminnasta Vuonna 2019

Yleisradion hallinto- neuvoston kertomus eduskunnalle yhtiön toiminnasta vuonna 2019 Yleisradion toiminnasta annetun lain 6 §:n mukaisesti yhtiön hallintoneuvosto antaa eduskunnalle kertomuksen Ylen julkisen palvelun toteutumisesta. K 6/2020 vp Yle – laadukas ja yksilöllinen HALLINTONEUVOSTON PUHEENJOHTAJA Tämä kertomus on ensimmäinen, jonka paljon paremmin kuin monet muut yleis- vuonna 2019 valittu Ylen hallintoneu- radioyhtiöt Euroopassa. Erityisesti Yle vosto antaa eduskunnalle. Samalla se Areenan suosio näkyy mittareissa. Se ker- on ensimmäinen kertomus, joka ajoittuu too siitä, että Yle on kyennyt tarjoamaan uuden eduskunnan toimikaudelle. Nykyi- monille suomalaisille juuri heitä kiinnos- nen eduskunnan liikenne- ja viestintäva- tavaa sisältöä. Ylen menestyminen kilpai- liokunta, sekä koko eduskunta, pääsee lussa lasten, nuorten ja nuorten aikuisten siten ensimmäistä kertaa tällä vaalikau- media-ajasta on samalla myös suomalai- della perusteellisesti arvioimaan Ylen toi- sen kulttuurin puolustamista. mintaa. Kunnallisalan kehittämissäätiön tutki- Suomalaisten silmissä Yle nauttii muksen mukaan 84 prosenttia suomalai- arvostusta. Yle tavoittaa viikossa 96 pro- sista piti Ylen tv-uutisia erittäin tai melko senttia suomalaisista ja päivittäin 78 pro- luotettavina. Lukema oli ylivoimaisesti senttia. Ilahduttavasti Ylen tavoittavuus korkein kaikista uutiskanavista. Yle tuot- on parantunut myös alle 45-vuotiaiden taa laajasti luotettavia uutisia sekä kan- keskuudessa. Mediakilpailu on erityisen sainvälisistä, valtakunnallisista että alu- -

Legal Assessment of State Aid Incompatible with the Internal Market

Legal assessment of State aid incompatible with the internal market Funding for online learning services and video-on-demand (“VOD”) to the Finnish public service broadcaster Yleisradio Oy (“Yle”) Before the European Commission 23 April 2021 Table of Contents I. Introduction ............................................................................................................................ 4 II. Factual background ............................................................................................................... 8 A. Overview of Sanoma ................................................................................................ 8 B. Overview of Yleisradio Oy and its activities .......................................................... 9 1. Yle’s public service remit .................................................................................. 10 2. Yle’s corporate governance and supervisory structure ..................................... 13 3. Yle’s financing .................................................................................................. 15 4. Yle’s broadcasting offering ............................................................................... 18 5. Yle’s non-broadcasting online activities ........................................................... 20 5.1. Yle’s expansion into online learning services ....................................... 22 5.2. Yle’s expansion into VOD .................................................................... 23 III. Legal assessment ................................................................................................................. -

Cirkulera-Hanke 2009-2012. Yhteistyöhankkeen Havainnot Ja Ratkaisut Piia Nordström & Maria Söderström

CIRKULERa-hankE 2009-2012. YHTEISTYÖHANKKEEN HAVAINNOT JA RATKAISUT Piia Nordström & Maria Söderström SERIE R: RAPPORTER, 2/2013 1 CIRKULERA-HANKE 2009-2012. PIENTYÖMAIDEN RAKENNUSJÄTE - YHTEISTYÖHANKKEEN HAVAINNOT JA RATKAISUT CIRKULERa-hankE 2009-2012. PIENTYÖMAIDEN RAKENNUSJÄTE - YHTEISTYÖHANKKEEN HAVAINNOT JA RATKAISUT PIIA NORDSTRÖM & MARIA SÖDERSTRÖM CIRKULERA!-hankkeestA Yrkeshögskolan Novian tiedotushanke Cirkulera!n (2009 kana olleissa länsiuusmaalaisissa kunnissa (Raasepori, Hanko, -2012) tavoitteena oli parantaa rakentajien jätehuoltotaitoja Siuntio ja Inkoo). Cirkulera-hanke oli EU-osarahoitteinen. sekä nostaa esiin lajittelun ja rakennusjätteen oikean käsit- Unionin myöntämä tuki tuli vuonna 2006 perustetusta Eu- telyn sekä jätteen vähentämisen etuja. Viranomaisten sekä roopan maaseudun kehittämisrahasto EJFLU:sta. jätehuollon yhteistyön kautta hanke pyrki myös kehittämään rakennusjätteeseen liittyviä toimintatapoja hankkeessa mu- SUMMARY IN ENGLISH The information project Cirkulera! (‘circulate’ or ‘recycle’ in ramme with the aim to improve the local entrepreneurs’ swedish) was a collaboration between municipalities, waste knowledge and routines when handling waste and to moti- companies and NOVIA University of Applied Science. vate them to sort and recycle waste accordingly. Cirkulera! was mainly funded by the EU/LEADER-prog- Utgivare: Yrkeshögskolan Novia, Fabriksgatan 1, Vasa, Finland © Piia Nordström, Maria Söderström & Yrkeshögskolan Novia Novia publikation och produktion, serie R: Rapporter 2/2013 ISSN: 1799-4179, ISBN: 978-952-5839-66-1 Layout: Jessica Taipale / Kommunikatören 2 SISÄLLYSLUETTELO 1 JohdanTo 4 2 CirKulera-HANKE 4 2.1. Esittely 4 2.2. Toimintaympäristö ja projektikumppanit 5 2.3. Kohderyhmä 5 3 JÄTehuollon ohjausKeinoT 5 3.1. Normiohjaus 5 3.1.1. Lainsäädäntö 5 3.1.2. Kuntatason määräykset ja niiden valvonta 5 3.1.3. Kunnallisia normiohjaustoimia muualla Suomessa 6 3.2. -

Changing Europe – the Power of Dialogue

Changing Europe – The Power of Dialogue 6 –12 October 2019, Potsdam Changing Europe – The Power of Dialogue 6 –12 October 2019, Potsdam hosted by supported by 2 Changing Europe – The Power of Dialogue In a world that is faster, more complicated and fragmented than ever, it is easy to only speak and never listen, to only tweet and never talk. Pressures of pace and finance are mounting. So it is more important than ever to have strong public service media that provide quality journalism that goes out of its way to be a trusted guide, to bring people together and set a tone that enables dialogue. PRIX EUROPA is ALL about dialogue: Come together from all corners of the continent to exchange views, to see/listen for yourself together with the others, to talk and discuss, to meet and be constructive, rather than judgmental or clever. Grab the opportunity to get into conversation, to change perspective, to challenge your opinions and take away inspiration, a shared experience and new ideas. Cilla Benkö PRIX EUROPA President Director General Sveriges Radio – SR 3 Changing Europe – The Power of Dialogue Dear friends and colleagues, PRIX EUROPA is dedicated to the ideal of a united Europe, which commits itself to democratic, ethical and cultural values. This ideal is, however, in acute danger. We have to dread being abruptly pulled out of a dream that we have been living for over six decades. Of all countries, the Mother of all Democracies, the United Kingdom, is separating itself from our community. Over our Europe of togetherness, that so many people envy us for, the threat of disaster is looming. -

The Fifth Periodic Report by the Government of Finland on the Implementation of the European Charter for Regional Or Minority Languages

THE FIFTH PERIODIC REPORT BY THE GOVERNMENT OF FINLAND ON THE IMPLEMENTATION OF THE EUROPEAN CHARTER FOR REGIONAL OR MINORITY LANGUAGES NOVEMBER 2017 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................................................... 6 PART I ................................................................................................................................................................... 7 1. BASIC INFORMATION ON FINNISH POPULATION AND LANGUAGES ................................................................ 7 1.1. Finnish population according to mother tongue ..................................................................................... 7 1.2. Administration of population data ......................................................................................................... 9 2. SPECIAL STATUS OF THE ÅLAND ISLANDS ....................................................................................................... 9 3. NUMBER OF SPEAKERS OF REGIONAL OR MINORITY LANGUAGES IN FINLAND .............................................. 10 3.1. The numbers of persons speaking a regional or minority language....................................................... 10 3.2. Swedish ............................................................................................................................................... 10 3.3. Sámi languages .................................................................................................................................. -

Radio Listening in Finland 2018

RADIO LISTENING IN FINLAND 2018 Tennispalatsi 5.2.2019 Lena Brun h:min Daily listening time is 2 hours 48 minutes 3:07 3:03 3:01 2:59 3:01 2:56 2:48 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 Total population, 9+ Source: Kansallinen Radiotutkimus, 2012-2018 yearly summaries #Radiovuosi2019 One million radio listeners on weekdays between 7:30 – 16:00 Quarter-hour audience on weekdays 1200 1000 800 (000) 600 400 200 0 Source: Kansallinen Radiotutkimus, 2018 yearly summary #Radiovuosi2019 Listening locations in 2018 Age under 45 Age over 45 1:22 min/day 3:47 min/day other other 5 % 5 % at home 23 % in car 20 % in car 39 % at home at work 63 % at work 12 % 33 % Source: Kansallinen Radiotutkimus, 2018 yearly summary #Radiovuosi2019 With which device did you listen to radio during the week? 88 % 77 % 33 % 18 % 11 % 8 % 5 % 4 % Radio Smartphone Computer Tablet under 45y 45+ years Source: Kansallinen Radiotutkimus, 2018 yearly summary #Radiovuosi2019 Smartphone usage is growing Which device did you use for radio listening during the week? 48 43 % 41 39 40 39 40 35 33 31 31 9-24 y 30 29 29 29 29 30 25 26 21 20 21 18 19 25-44 y 11 11 11 9 9 7 7 8 8 5 6 6 45+ y 3-5/ 6-8/ 9-11/ 3-5/ 6-8/ 9-11/ 3-5/ 6-8/ 9-11/ 2016 2016 2016 2017 2017 2017 2018 2018 2018 12/2015- 12/2016- 12/2017- 2/2016 2/2017 2/2018 Source: Kansallinen Radiotutkimus #Radiovuosi2019 Weekly radio reach is 2018 92 % Daily radio reach is of the population (9+) 71 % of the population (9+) Source: Kansallinen Radiotutkimus, 2018 yearly summary #Radiovuosi2019 Weekly reach by radio station Total -

Ihan Sama Sivu 23

2/ 2013 Poimintoja Ylen tarjonnasta keväällä 2014 | Gott och blandat ur Yles utbud Ihan sama SIVU 23 4 Kotikatsomo • 16 Siskonpeti 28 Valokuvan voimaa • 30 Tjockare än vatten 36 Jake Nyman 1 SISÄLTÖ YLE ESITTÄÄ Innehåll Poimintoja keväästä PÄÄTOIMITTAJA Elina Ristmeri 3 Pääkirjoitus Ylen kevätohjelmisto tarjoaa paljon mielenkiintoisia uutuuk- → Yle Fem TOIMITUSSIHTEERI Tanja Tähti sia. Henkilökohtaisesti odotan hulvatonta huumoria kotimaisten → Yle TV1 30 Tjockare än vatten (Vettä sakeampaa) naiskoomikoiden parhaimmistolta Siskonpeti-sarjassa, jota täh- VALOKUVAT dittävät loistavat Niina Lahtinen, Pirjo Heikkilä, Sanna Stellan ja 4 Kotikatsomo: Hyväntekijä 31 Lilyhammer (16) Esitteen kuvatoimittaja Krisse Salminen. Kotikatsomo: Raja 32 Gamla onsdag (Konkarikeskiviikko) Seppo Sarkkinen, 5 Ylen Kuvapalvelu ja Sunnuntai-aamupäivisin kannattaa kääntää Yle Radio Suo- 6 Kotikatsomo: Hiljaisuus (12) 33 Simon tuotantoyhtiöt & All Over Press men taajuudelle, kun legendaarinen Jake Nyman aloittaa uuden, nimeänsä kantavan show'n. Arkisin radion puolella joka päivä klo Kotikatsomo: Le Havre (S) 7 ESITTEEN TYÖRYHMÄ 13 Yle Puheessa on luvassa keskusteluja, vetäjinä muun muas- → Yle Radio 1 Niina Broman, Mari Clusius, Dokumenttiprojekti: Alaska Highway 8 Aila Havia-Venäläinen, sa radioon seitsemän vuoden tauon jälkeen paluun tekevä Jenni Dokumenttiprojekti: Päästökauppiaat Utelias seikkailija, rauhallinen paneutuja 34 Tuire Juusela, Kaisa Kirves, Pääskysaari. Dokumenttiprojekti: Piripäiväkirja 35 Orhan Pamuk: Nimeni on Punainen Taina Kivistö, Gitte Laurell, Ja muistattehan, että helmikuussa on tulossa Sotshin olym- Daniel Nylund, 9 Aarteenetsijät pialaisia todella runsas paketti: lähetystunteja tulee televisiossa Anna Raatikainen, lähes 350, radiossa yli 200 ja netissä n. 500 tuntia. Netissä tarjo- 12 Mr Selfridge (12) → Yle Radio Suomi Elina Ristmeri, Katja Riuttu-Sillanpää, taan lisäksi Sotshi Areena -palvelu, jonka avulla voi katsoa suora- Top of the Lake (16) Jake Nyman 13 36 Mona Selenius na lajia kuin lajia niin tietokoneella, tabletilla kuin älypuhelimella.