Agape, Philia and Eros Anca Simitopol Thesis Submi

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Network Map of Knowledge And

Humphry Davy George Grosz Patrick Galvin August Wilhelm von Hofmann Mervyn Gotsman Peter Blake Willa Cather Norman Vincent Peale Hans Holbein the Elder David Bomberg Hans Lewy Mark Ryden Juan Gris Ian Stevenson Charles Coleman (English painter) Mauritz de Haas David Drake Donald E. Westlake John Morton Blum Yehuda Amichai Stephen Smale Bernd and Hilla Becher Vitsentzos Kornaros Maxfield Parrish L. Sprague de Camp Derek Jarman Baron Carl von Rokitansky John LaFarge Richard Francis Burton Jamie Hewlett George Sterling Sergei Winogradsky Federico Halbherr Jean-Léon Gérôme William M. Bass Roy Lichtenstein Jacob Isaakszoon van Ruisdael Tony Cliff Julia Margaret Cameron Arnold Sommerfeld Adrian Willaert Olga Arsenievna Oleinik LeMoine Fitzgerald Christian Krohg Wilfred Thesiger Jean-Joseph Benjamin-Constant Eva Hesse `Abd Allah ibn `Abbas Him Mark Lai Clark Ashton Smith Clint Eastwood Therkel Mathiassen Bettie Page Frank DuMond Peter Whittle Salvador Espriu Gaetano Fichera William Cubley Jean Tinguely Amado Nervo Sarat Chandra Chattopadhyay Ferdinand Hodler Françoise Sagan Dave Meltzer Anton Julius Carlson Bela Cikoš Sesija John Cleese Kan Nyunt Charlotte Lamb Benjamin Silliman Howard Hendricks Jim Russell (cartoonist) Kate Chopin Gary Becker Harvey Kurtzman Michel Tapié John C. Maxwell Stan Pitt Henry Lawson Gustave Boulanger Wayne Shorter Irshad Kamil Joseph Greenberg Dungeons & Dragons Serbian epic poetry Adrian Ludwig Richter Eliseu Visconti Albert Maignan Syed Nazeer Husain Hakushu Kitahara Lim Cheng Hoe David Brin Bernard Ogilvie Dodge Star Wars Karel Capek Hudson River School Alfred Hitchcock Vladimir Colin Robert Kroetsch Shah Abdul Latif Bhittai Stephen Sondheim Robert Ludlum Frank Frazetta Walter Tevis Sax Rohmer Rafael Sabatini Ralph Nader Manon Gropius Aristide Maillol Ed Roth Jonathan Dordick Abdur Razzaq (Professor) John W. -

Reinventar La Izquierda En El Siglo Xxi

Reinventar la izquierda en el siglo xxi José Luis Coraggio y Jean-Louis Laville (organizadores) Reinventar la izquierda en el siglo xxi Hacia un diálogo Norte-Sur Reinventar la izquierda en el siglo XXI : hacia un dialogo norte-sur / José Luis Coraggio ... [et.al.] ; coordinado por José Luis Coraggio y Jean-Louis Laville. - 1a ed. - Los Polvorines : Universidad Nacional de General Sarmiento, 2014. 548 p. ; 21x15 cm. ISBN 978-987-630-192-3 1. Teorías Polìticas. I. Coraggio, José Luis II. Coraggio, José Luis, coord. III. Laville, Jean-Louis, coord. CDD 320.1 Fecha de catalogación: 07/08/2014 © Universidad Nacional de General Sarmiento, 2014 J. M. Gutiérrez 1150, Los Polvorines (B1613GSX) Prov. de Buenos Aires, Argentina Tel.: (54 11) 4469-7578 [email protected] www.ungs.edu.ar/ediciones Traducción del inglés: Gabriela Ventureira. Traducción del francés: Marie Bardet con la colaboración de Carlos Pérez. Diseño de colección: Andrés Espinosa - Departamento de Publicaciones - UNGS / Alejandra Spinelli Corrección: Edit Marinozzi Hecho el depósito que marca la Ley 11723 Prohibida su reproducción total o parcial Derechos reservados Impreso en Docuprint S. A. Calle Taruarí 123 (C1071AAC) Ciudad de Buenos Aires, Argentina, en el mes de septiembre de 2014. Tirada: 400 ejemplares. Índice Reconocimientos .....................................................................................11 PRESENTACIÓN POR LA UNGS / Eduardo Rinesi ................................... 13 PRESENTACIÓN POR EL IAEN / Guillaume Long ....................................17 INTRODUCCION GENERAL / José Luis Coraggio y Jean-Louis Laville ..... 21 Otra política, otra economía, otras izquierdas / José Luis Coraggio ........ 35 Izquierda europea y proyecto emancipador / Jean-Louis Laville .............. 85 Mensajes a la izquierda de ayer y a la de hoy / Guy Bajoit ..................... -

PDF Download Resurrection from the Underground: Feodor

RESURRECTION FROM THE UNDERGROUND: FEODOR DOSTOEVSKY PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Andrew B Hammond Professor of French Language Literature and Civilization Rene Girard,James G Williams | 120 pages | 15 Feb 2012 | Michigan State University Press | 9781611860375 | English | East Lansing, MI, United States Resurrection from the Underground: Feodor Dostoevsky PDF Book Coming "from above" the Swiss mountains , he physically resembles common depictions of Jesus Christ : slightly larger than average, with thick, blond hair, sunken cheeks and a thin, almost entirely white goatee. Learn More. Important Quotations Explained. On 14 April , they began a delayed honeymoon in Germany with the money gained from the sale. Russian author. Dostoevsky disliked the academy, primarily because of his lack of interest in science, mathematics and military engineering and his preference for drawing and architecture. Ivan, however, has stated that he is against Christ. On the following day, Dostoevsky suffered a pulmonary haemorrhage. The Grand Inquisitor Anthropocentric. Anyone interested in Dostoevsky will profit from grappling with Girard's take. Main article: Poor Folk. Ci tengo a precisare che il saggio - per sua natura - contiene spoiler di tutti i romanzi, ergo andrebbe letto a seguito del recupero dell'opera omnia. XXII, Nos. Some critics, such as Nikolay Dobrolyubov , Ivan Bunin and Vladimir Nabokov , viewed his writing as excessively psychological and philosophical rather than artistic. Resurrection from the Underground: Feodor Dostoevsky pp. Minihan, Michael A. See templates for discussion to help reach a consensus. LOG IN. Arshad Khan says: Reply December 17, at pm. C-1 Download Save contents. This aspect leads the narrator into doing wrong things. Yale University Press. -

Individualism and Socialism

INDIVIDUALISM AND SOCIALISM. (1834) By Pierre Leroux AND OTHER WRITINGS ON THE DOCTRINE OF HUMANITY INDIVIDUALISM AND SOCIALISM. (1834.—After the massacres on the Rue Transnonain.) At times, even the most resolute hearts, those most firmly focused on the sacred beliefs of progress, lose courage and feel themselves full of disgust with the present. In the 16th century, when we murdered in our civil wars, it was in the name of God and with a crucifix in hand; it was a question of the most sacred things, of things which, once they have secured our conviction and our faith, dominate our natures so legitimately that there is nothing to do but obey, and even our most precious prerogatives are voluntarily sacrificed to the divine will. In the name of what principle do we today send off, by telegraph, pitiless orders, and transform proletarian soldiers into the executioners of their own class? Why has our era seen cruelties which recall St. Bartholemew? Why have men been fanaticized to the point of making them slaughter the elderly, women, and children in cold blood? Why has the Seine rolled with murders which recall the arquebuscades from the windows of the Louvre? It is not in the name of God and eternal salvation that these things are done. It is in the name of material interests. Our century is, it seems, quite vile, and we have degenerated even from the crimes of our fathers. To kill in the manner of Charles IX or Torquemada, in the name of faith and the Church, because one believes that God desires it, because one has a fanatic spirit, exalted by the fear of hell and the hope of paradise, is still to have some grandeur and some generosity in one's crime. -

ABSTRACT Dostoevsky's View of the Russian Soul and Its Impact on the Russian Question in the Brothers Karamazov Paul C. Schlau

ABSTRACT Dostoevsky’s View of the Russian Soul and its Impact on the Russian Question in The Brothers Karamazov Paul C. Schlaudraff Director: Adrienne M. Harris, Ph.D Fyodor Dostoevsky, one of Russia’s most renowned novelists, profoundly affected the way that Russia would think of itself in the years following his death. One of the most important issues for Dostoevsky and other authors at the time was the reconciliation of the peasant and noble classes in the aftermath of the serf emancipation in Russia. Dostoevsky believed that the solution to this issue would come from the Russian peasantry. My research investigates Dostoevsky’s view of the “Russian soul”, which is the particular set of innate characteristics which distinguishes Russians from other nationalities. Furthermore, it examines how Dostoevsky’s view of the Russian soul affected his answer to the question of Russia’s ultimate destiny. During the 19th century, socialism was an especially popular answer to that question. Dostoevsky, however, presented an entirely different solution. Through a thorough examination of Dostoevsky’s final novel, The Brothers Karamazov, my thesis demonstrates this alternative solution and its significance in light of competing Russian theory during the 19th century. APPROVED BY DIRECTOR OF HONORS THESIS ______________________________________________________ Dr. Adrienne M. Harris, Department of Modern Languages APPROVED BY THE HONORS PROGRAM: ______________________________________________ Dr. Andrew Wisely, Director DATE: ________________________ DOSTOEVSKY’S VIEW OF THE RUSSIAN SOUL AND ITS IMPACT ON THE RUSSIAN QUESTION IN THE BROTHERS KARAMAZOV A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Baylor University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Honors Program By Paul C. -

From Marx to Ecosocialism

SOCIALISMANDECOLOGY From Marx to Ecosocialism* ByMichaelLöwy Since the industrial revolution, capitalist societies (and more recently,thelatebureaucraticsocietiesofEasternEurope)havebeen characterized by an ever-growing rationalization. Following Max Weber,wecandistinguishthreecloselyrelatedaspectsofthis: 1)Zweckrationalitat,ortherationality-of-ends,thatis,theutilizationof rational means to attain objectives that are not at all rational themselves.Bureaucracyistheideal-typicalinstitutionalexpressionof this pattern. This is what the Frankfurt School referred to as instrumentalrationality,atypeof ratio compatiblewith themost monstroussubstantiveirrationalities—therational-bureaucraticadmin- istrationofgenocide,forinstance,totakethelimitingcase.Butapart fromsuchextremes,asErnestMandelhaspointedout,thecombination of partial rationality with overall irrationality is intrinsic to the “normal”functioningofthecapitalisteconomyanditsbureaucratic institutions.1 2)Thedifferentiationandautonomizationofdomains,resultinginthe separationoftheeconomic,social,political,andculturalspheres.The marketeconomybecomesaself-regulatingsystemthatisnolonger “embedded”inthesociety(tousePolanyi’sfamousexpression),thereby escapingsocial,moral,orpoliticalcontrol. 3)Rechenhaftigkeit,orthespiritofrationalcalculationandthegeneral tendency to quantification. This tendency finds its most direct *TranslatedbyK.PMosely.Quoteshavebeentranslatedbutthecitedtexts aretheoriginals. 1Ernest Mandel, Power and Money: A Marxist Theory of Bureaucracy (London:Verso,1992),p.182. CNS,13(1),March,2002 -

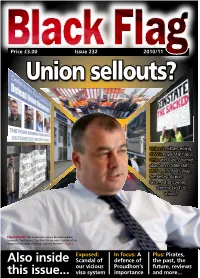

Also Inside This Issue

PricePrice £3.00 £3.00 IssueIssue 232 229 Mid 2010/11 2009 Union sellouts? Unison’s militant exiling, CWU’s Royal Mail fiasco, Unite and Gate Gourmet, abandoned Mitie staff, NUT and St Paul’s Way, the Belfast Airport farce... what’s wrong with the big TUC unions? Figurehead: TUC general secretary Brendan Barber lambasts “bad bosses,” but do the member unions of his organisation really stand up when it matters? Page 7 Exposed: In focus: A Plus: Pirates, Also inside Scandal of defence of the past, the our vicious Proudhon’s future, reviews this issue... visa system importance and more... Editorial Welcome to issue 232 of Black Flag, which coincides once again with the annual London Anarchist Bookfair, the largest and longest-running event of its kind in the world. Now that this issue is the 7th published by the “new” collective we can safely drop the “new” bit! We believe that we have come a long way with Black Flag. As a very small collective we have managed to publish and sustain a consistent and high-quality, twice yearly, class- struggle anarchist publication on a shoe-string budget and limited personnel. Before proceeding further, we would like to make our usual appeal for more people to get involved with the editorial group. The more people who get involved, the more Black Flag will grow with increased frequency and wider distribution etc. This issue includes our usual eclectic mix of libertarian-left theory, history, debate, analysis and reportage. Additionally, this issue is again somewhat of an anniversary issue, which acknowledges two significant events. -

"To Each According to Ability": Saint-Simon on Equality of Opportunity

"To each according to ability": Saint-Simon on equality of opportunity Presentation by Luc Bovens Equality of Opportunity Conference Center for Law, Economics and Public Policy Duke University 24-25 May 2016 [email protected] My presentation will draw on the attached two papers: pp. 2-16: “To or From Each according to What? Biblical Origins and Development of Early Socialist Slogans” This is a joint paper with Adrien Lutz. In particular section 3 “To each according to his ability” is relevant. pp. 17-31: “The Difference Principle and the Distribution of Education and Resources versus the Redistribution of Revenues” This is a joint working paper with Caleb South with input from Marc Fleurbaey. It is an attempt to spell out a model inspired by Saint-Simon’s slogan “To each according to his ability”. It is very much early work. Comments are much appreciated. 1 To or From Each according to What? Biblical Origins and Development of Early Socialist Slogans Luc Bovens and Adrien Lutz 16 May 2016 [email protected] and [email protected] 1. Three Slogans Marx writes in the Critique of the Gotha Program in 1875 that the Communist society can write the following slogan on its flag: “From each according to his abilities; To each according to his needs”. There are earlier versions of the same slogan in Louis Blanc in 1848, Étienne Cabet in 1845, and of the second half of the slogan in Constantin Pecqueur in 1842.1 Before that there were versions of a different slogan in the early socialist literature, viz. -

Socialism As a Cultural Movement?

REVIEW ESSAY Ahlrich Meyer SOCIALISM AS A CULTURAL MOVEMENT? WEBER, PETRA. Sozialismus als Kulturbewegung. Fruhsozialistische Ar- beiterbewegung und das Entstehen zweier feindlicher Bruder Marxismus und Anarchismus. [Beitrage zur Geschichte des Parlamentarismus und der politischen Parteien, Band 86.] Droste Verlag, Diisseldorf 1989. 545 pp. DM 98.00. There is nothing wrong in tackling the intellectual history of social move- ments from a contemporary interest and perspective. Such an approach often uncovers things previously buried under the debris of received wis- dom. Moreover, early socialism, the topic under discussion here, has long been used as a screen on which to project topical ideological arguments. This dissertation by Petra Weber on the "early socialist labour movement and the rise of the two hostile brothers Marxism and anarchism" (thus the subtitle), sponsored by the Friedrich Ebert Stiftung, supervised by Profes- sor Heinrich August Winkler and Professor Wilhelm Hennis and published by the Bonn Commission on Parliamentary History and Political Parties, is the latest attempt to respond to "the demand for alternative concepts of socialism" (p. 13) by recalling socialist traditions preceding and contempo- raneous with Marx. The author stresses primarily two themes in her at- tempted actualization: firstly she highlights the much neglected continuity between early socialism and anarchism and endeavours to reverse the suppression of anarchism from the history of socialism, and secondly she relies on the change of paradigm in sociohistorical research pioneered by E. P. Thompson and others by adopting a broad notion of "working-class culture" and the labour movement as a "cultural movement". Together these provide the thesis of her book, namely that "the continuity of early socialism and anarchism must be sought in its self-image as a cultural movement" (p. -

H-France Review Volume 17 (2017) Page 1

H-France Review Volume 17 (2017) Page 1 H-France Review Vol. 17 (December 2017), No. 242 Julian Wright, Socialism and the Experience of Time: Idealism and the Present in Modern France. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017. Chronology, bibliography, and index. xv + 276 pp. $97.50 U.S. (cl). ISBN 978-0-19-953358-9. Review by K. Steven Vincent, North Carolina State University. Anglo-American historians of my generation, when they looked to the political and social thought of the Third Republic, devoted most attention either to the founders of sociology, to existentialists, or to figures and movements of the radical Left and Right – extreme nationalists, anti-Semites, and proto-fascists on the right; terrorists, anarchists, syndicalists, and revolutionary socialists on the left. Julian Wright represents a new generation of English-language historians looking at figures and movements between the extremes. Wright’s first book was about the regionalist movement during the Belle Époque, and it focused on the intellectual and organizational leader of this movement, Jean Charles-Brun.[1] Wright situated Charles- Brun within a French political discourse that recommended regionalism, federalism, conciliation, and gradualist praxis, a discourse that extended back to the Old Regime, but grew in importance during the nineteenth century, as prominent intellectuals like Pierre-Joseph Proudhon criticized the state and recommended mutualist and federalist organizational forms. Charles-Brun, Wright insisted, should be placed at the center of the French political tradition that looked to regional bodies to make reforms, one that respected the cultures and particular needs of local populations. Wright took a generous view of what Anne-Marie Thiesse termed Charles-Brun’s “consensual nationalism,”[2] arguing that even when Charles-Brun served on the Commission des Provinces set up by Pétain, he was not a collaborator, but instead was pushing for moderate reforms, an agenda that avoided socio-political abstractions and focused on quotidian concerns. -

The Intellectual Origins of French Jacobin Socialism

LEO A. LOUBERE THE INTELLECTUAL ORIGINS OF FRENCH JACOBIN SOCIALISM This essay was written with the thought in mind that there is need for more clarification in the terminology used to describe certain socialist philosophies of the nineteenth century. It seems clear that the terms "democratic socialism" or "social democracy" have lost much of the meaning they might have had in the past. "Democratic" as an adjec- tive or "democracy" as a noun, have been so abused that today they may convey the idea of either a civil libertarian kind of government or a form of totalitarianism. Indeed, the words made for confusion in the nineteenth century when Jacobins, Babouvians, Blanquists, even Bonapartists, claimed each to be true representatives of the general will, and either executed or would have executed those representing opposing wills. Nonviolent were P.-J.-B. Buchez and Louis Blanc, each of whom claimed to be a democratic socialist. Yet in 1848 they opposed each other with intense vehemence. There is need then, for definition and delineation. The problem of clarification involves a reinterpretation of certain socialist ideologies and a more definite understanding of the forces which brought about the politicizing of them. For France, only one author made this latter topic the subject of a special study.1 However, he fell somewhat short of his goal, especially for the pre-18 48 period, the one with which this essay deals. The purpose of this study, there- fore, is to offer a more precise explanation concerning the origin of one of the currents of early socialist philosophy, called here Jacobin socialism. -

Karl Marx Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844

Karl Marx Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844 Karl Marx, Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844. Progress Publishers, Moscow 1959; Translated by Martin Milligan, revised by Dirk J. Struik, contained in Marx/Engels, Gesamtausgabe, Abt. 1, Bd. 3. First Manuscript Wages of Labor Wages are determined through the antagonistic struggle between capitalist and worker. Victory goes necessarily to the capitalist. The capitalist can live longer without the worker than can the worker without the capitalist. Combination among the capitalists is customary and effective; workers’ combination is prohibited and painful in its consequences for them. Besides, the landowner and the capitalist can make use of industrial advantages to augment their revenues; the worker has neither rent nor interest on capital to supplement his industrial income. Hence the intensity of the competition among the workers. Thus only for the workers is the separation of capital, landed property, and labour an inevitable, essential and detrimental separation. Capital and landed property need not remain fixed in this abstraction, as must the labor of the workers. The separation of capital, rent, and labor is thus fatal for the worker. The lowest and the only necessary wage rate is that providing for the subsistence of the worker for the duration of his work and as much more as is necessary for him to support a family and for the race of laborers not to die out. The ordinary wage, according to Smith, is the lowest compatible with common humanity6, that is, with cattle-like existence. The demand for men necessarily governs the production of men, as of every other commodity.