Individualism and Socialism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reinventar La Izquierda En El Siglo Xxi

Reinventar la izquierda en el siglo xxi José Luis Coraggio y Jean-Louis Laville (organizadores) Reinventar la izquierda en el siglo xxi Hacia un diálogo Norte-Sur Reinventar la izquierda en el siglo XXI : hacia un dialogo norte-sur / José Luis Coraggio ... [et.al.] ; coordinado por José Luis Coraggio y Jean-Louis Laville. - 1a ed. - Los Polvorines : Universidad Nacional de General Sarmiento, 2014. 548 p. ; 21x15 cm. ISBN 978-987-630-192-3 1. Teorías Polìticas. I. Coraggio, José Luis II. Coraggio, José Luis, coord. III. Laville, Jean-Louis, coord. CDD 320.1 Fecha de catalogación: 07/08/2014 © Universidad Nacional de General Sarmiento, 2014 J. M. Gutiérrez 1150, Los Polvorines (B1613GSX) Prov. de Buenos Aires, Argentina Tel.: (54 11) 4469-7578 [email protected] www.ungs.edu.ar/ediciones Traducción del inglés: Gabriela Ventureira. Traducción del francés: Marie Bardet con la colaboración de Carlos Pérez. Diseño de colección: Andrés Espinosa - Departamento de Publicaciones - UNGS / Alejandra Spinelli Corrección: Edit Marinozzi Hecho el depósito que marca la Ley 11723 Prohibida su reproducción total o parcial Derechos reservados Impreso en Docuprint S. A. Calle Taruarí 123 (C1071AAC) Ciudad de Buenos Aires, Argentina, en el mes de septiembre de 2014. Tirada: 400 ejemplares. Índice Reconocimientos .....................................................................................11 PRESENTACIÓN POR LA UNGS / Eduardo Rinesi ................................... 13 PRESENTACIÓN POR EL IAEN / Guillaume Long ....................................17 INTRODUCCION GENERAL / José Luis Coraggio y Jean-Louis Laville ..... 21 Otra política, otra economía, otras izquierdas / José Luis Coraggio ........ 35 Izquierda europea y proyecto emancipador / Jean-Louis Laville .............. 85 Mensajes a la izquierda de ayer y a la de hoy / Guy Bajoit ..................... -

Agape, Philia and Eros Anca Simitopol Thesis Submi

Ideas of Community in the Thought of Pierre Leroux and of Feodor Dostoevsky: Agape , Philia and Eros Anca Simitopol Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the PhD degree in Political Science Supervisor: Gilles Labelle Political Studies Social Sciences University of Ottawa ©Anca Simitopol, Ottawa, Canada, 2012 Contents ABSTRACT ……………………………………………………………………… iv INTRODUCTION ……………………………………………………………… 1 CHAPTER ONE Two Critics of “Possessive Individualism” ………………………………….. 11 1.1. Introduction ……………………………………………………………... 11 1.2. Leroux as a liberal …………………………………………………......... 27 1.3. Leroux’s anthropology: Liberté, Égalité, Fraternité …………………... 37 1.4. Division of society, division of the self and eclecticism ………………... 42 1.5. Freedom according to Leroux …………………………………………... 47 1.6. Property according to Leroux …………………………………………… 58 1.7. Dostoevsky as political thinker ………………………………………….. 68 1.8. The poor and the ontological meaning of capitalism ………………….. 70 1.9. “Possessive Individualism” in Russia …………………………………… 82 1.10. From individualism to the revolutionary affirmation of the will-to-power 1.10.1. Raskolnikov ………………………………………………….. 93 1.10.2. The case of “The possessed” ………………………………... 98 1.11. Conclusion …………………………………………………………… 105 CHAPTER TWO Varieties of Socialism and of Utopia ………………………………………. 115 2.1. Introduction ...………………………………………………………… 115 2.2. Dostoevsky’s critique of socialism: “Shigalovism” …………………. 130 2.3. Leroux’s critique of Fourier’s socialism ……………………………. 144 2.4. Introduction to utopia ………………………………………………... 149 2.5. Transformation of utopia in the 19 th century ……………………….. 158 2.6. Saint-Simon: oscillation between transcendence and immanence .... 171 2.7. The Saint-Simonian School: utopia transformed into political program …………………………………………………….. 180 2.8. The Grand Inquisitor and the incompatibility between freedom and unity ……………………………………………………. 193 2.9. Dostoevsky: a dialogical utopia ……………………………………… 207 2.10. -

From Marx to Ecosocialism

SOCIALISMANDECOLOGY From Marx to Ecosocialism* ByMichaelLöwy Since the industrial revolution, capitalist societies (and more recently,thelatebureaucraticsocietiesofEasternEurope)havebeen characterized by an ever-growing rationalization. Following Max Weber,wecandistinguishthreecloselyrelatedaspectsofthis: 1)Zweckrationalitat,ortherationality-of-ends,thatis,theutilizationof rational means to attain objectives that are not at all rational themselves.Bureaucracyistheideal-typicalinstitutionalexpressionof this pattern. This is what the Frankfurt School referred to as instrumentalrationality,atypeof ratio compatiblewith themost monstroussubstantiveirrationalities—therational-bureaucraticadmin- istrationofgenocide,forinstance,totakethelimitingcase.Butapart fromsuchextremes,asErnestMandelhaspointedout,thecombination of partial rationality with overall irrationality is intrinsic to the “normal”functioningofthecapitalisteconomyanditsbureaucratic institutions.1 2)Thedifferentiationandautonomizationofdomains,resultinginthe separationoftheeconomic,social,political,andculturalspheres.The marketeconomybecomesaself-regulatingsystemthatisnolonger “embedded”inthesociety(tousePolanyi’sfamousexpression),thereby escapingsocial,moral,orpoliticalcontrol. 3)Rechenhaftigkeit,orthespiritofrationalcalculationandthegeneral tendency to quantification. This tendency finds its most direct *TranslatedbyK.PMosely.Quoteshavebeentranslatedbutthecitedtexts aretheoriginals. 1Ernest Mandel, Power and Money: A Marxist Theory of Bureaucracy (London:Verso,1992),p.182. CNS,13(1),March,2002 -

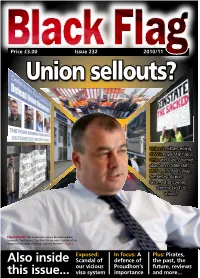

Also Inside This Issue

PricePrice £3.00 £3.00 IssueIssue 232 229 Mid 2010/11 2009 Union sellouts? Unison’s militant exiling, CWU’s Royal Mail fiasco, Unite and Gate Gourmet, abandoned Mitie staff, NUT and St Paul’s Way, the Belfast Airport farce... what’s wrong with the big TUC unions? Figurehead: TUC general secretary Brendan Barber lambasts “bad bosses,” but do the member unions of his organisation really stand up when it matters? Page 7 Exposed: In focus: A Plus: Pirates, Also inside Scandal of defence of the past, the our vicious Proudhon’s future, reviews this issue... visa system importance and more... Editorial Welcome to issue 232 of Black Flag, which coincides once again with the annual London Anarchist Bookfair, the largest and longest-running event of its kind in the world. Now that this issue is the 7th published by the “new” collective we can safely drop the “new” bit! We believe that we have come a long way with Black Flag. As a very small collective we have managed to publish and sustain a consistent and high-quality, twice yearly, class- struggle anarchist publication on a shoe-string budget and limited personnel. Before proceeding further, we would like to make our usual appeal for more people to get involved with the editorial group. The more people who get involved, the more Black Flag will grow with increased frequency and wider distribution etc. This issue includes our usual eclectic mix of libertarian-left theory, history, debate, analysis and reportage. Additionally, this issue is again somewhat of an anniversary issue, which acknowledges two significant events. -

Socialism As a Cultural Movement?

REVIEW ESSAY Ahlrich Meyer SOCIALISM AS A CULTURAL MOVEMENT? WEBER, PETRA. Sozialismus als Kulturbewegung. Fruhsozialistische Ar- beiterbewegung und das Entstehen zweier feindlicher Bruder Marxismus und Anarchismus. [Beitrage zur Geschichte des Parlamentarismus und der politischen Parteien, Band 86.] Droste Verlag, Diisseldorf 1989. 545 pp. DM 98.00. There is nothing wrong in tackling the intellectual history of social move- ments from a contemporary interest and perspective. Such an approach often uncovers things previously buried under the debris of received wis- dom. Moreover, early socialism, the topic under discussion here, has long been used as a screen on which to project topical ideological arguments. This dissertation by Petra Weber on the "early socialist labour movement and the rise of the two hostile brothers Marxism and anarchism" (thus the subtitle), sponsored by the Friedrich Ebert Stiftung, supervised by Profes- sor Heinrich August Winkler and Professor Wilhelm Hennis and published by the Bonn Commission on Parliamentary History and Political Parties, is the latest attempt to respond to "the demand for alternative concepts of socialism" (p. 13) by recalling socialist traditions preceding and contempo- raneous with Marx. The author stresses primarily two themes in her at- tempted actualization: firstly she highlights the much neglected continuity between early socialism and anarchism and endeavours to reverse the suppression of anarchism from the history of socialism, and secondly she relies on the change of paradigm in sociohistorical research pioneered by E. P. Thompson and others by adopting a broad notion of "working-class culture" and the labour movement as a "cultural movement". Together these provide the thesis of her book, namely that "the continuity of early socialism and anarchism must be sought in its self-image as a cultural movement" (p. -

![Bakunin's Writings, [Edited] by Guy A. Aldred](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7915/bakunins-writings-edited-by-guy-a-aldred-1997915.webp)

Bakunin's Writings, [Edited] by Guy A. Aldred

Bakunin, Mikhail Aleksandrovich Bakunin s Writings AKUNIN S WRITINGS BY CUY A. ALDRED. MODERN PUBLISHERS, INDORE. Available at LIBERTARIAN BOOK HOUSE, Arya Bhavan, Sandhurst Road, BOMBAY, 4. E RS. 2/- Published by: MODERN PUBLISHERS, INDORE CITY. IMPORTANT NOTICE. Books and Pamphlets published by the Modern Publishers of Indore and those of other Publishers that are sold by Libertarian Book House, are sold on the condition that they will be taken back if not approved within a week from the sale date and full amount of the cost minus 5% will be refunded to the purchaser if the books returned are in good condition and are not spoiled. As we are confident that our books give full value for the money so there will be very few returns. i Please take advantage of this offer and ask for list of the books which will be supplied free anywli in India. MANAGER, THE LIBERTARIAN BOOK HOU*E. Printed by: C. M. SHAH, MODERN PRINTERY LX>., INDORE CITY. MUTUAL BANKING BY GREENE. SOME OF THF CONTENTS. Value, Currency, The Disadvantages of a Specie Currency. The Business of Banking. \ Bills of Exchange. The rate of Interest, Advantages of Mutual Banking. \ : Mutual money Generally Competent to Force its oiWC . Way !~j If Into General Circulation. The Measure of Value. The Regulator of value. The Provincial Land Bank. Money, Advantage of a Mutual Currency. Credit, Legitimate Credit. Credit Mutual Bank in Operation, Price Us. 1-4-0. Available at: LIBERTARIAN BOOK HOUSE, ARYA BHAVAN, SANDHURST ROAD, BOMBAY, 4. OR MODERN PUBLISHERS, INDORE CITY RISE & FALL OF THE COMINTERN by K. -

French Newspapers and Ephemera from the 1848 Revolution

FRENCH NEWSPAPERS AND EPHEMERA FROM THE 1848 REVOLUTION MORNA DANIELS THE British Library has exceptionally fine holdings relating to the French Revolution of 1789. The three collections purchased from or on the recommendation of John Wilson Croker comprise 48,579 pieces and have been briefly listed with some indication of subject, but not all have been catalogued.^ The 'R* set, the last to be purchased in 1856, includes a few items from the revolution of 1830. In 1898 Francois Chevremont, Marat's biographer, presented seventy volumes of works by or about Marat. ^ Croker himself lived to see the French Revolution of 1848. This event sparked off uprisings thoughout Europe, in Milan, Hanover, Munich, Prague, Vienna, Hungary, Prussia and Poland, and encouraged the Chartist movement in London. It swept away the 'bourgeois' King Louis-Philippe, and ushered in a period of political instability in France which led to the rise to power of Louis-Napoleon, nephew of Napoleon I. It is represented in the British Library by an interesting small collection of newspapers, prints, election material and other ephemera, placed at shelfmark HS.74/1217. Who formed this collection is not entirely clear. Included among the ephemera is a registration form to vote in the plebiscite of 1852 filled in by Charles Viennot, an 'employe' (clerk) born in i8i8, and hving at 9 rue des Mathurins, noted as being in the ist arrondissement (fig. i). The rue des Mathurins, now in the 8th and 9th arrondissements, was named after a farm belonging to the Mathurin order."^ On maps of the time it is marked as rue neuve des Mathurins, as there was another rue des Mathurins near the Roman baths (now the Cluny Museum), which has since been destroyed. -

The Intellectual Origins of French Jacobin Socialism

LEO A. LOUBERE THE INTELLECTUAL ORIGINS OF FRENCH JACOBIN SOCIALISM This essay was written with the thought in mind that there is need for more clarification in the terminology used to describe certain socialist philosophies of the nineteenth century. It seems clear that the terms "democratic socialism" or "social democracy" have lost much of the meaning they might have had in the past. "Democratic" as an adjec- tive or "democracy" as a noun, have been so abused that today they may convey the idea of either a civil libertarian kind of government or a form of totalitarianism. Indeed, the words made for confusion in the nineteenth century when Jacobins, Babouvians, Blanquists, even Bonapartists, claimed each to be true representatives of the general will, and either executed or would have executed those representing opposing wills. Nonviolent were P.-J.-B. Buchez and Louis Blanc, each of whom claimed to be a democratic socialist. Yet in 1848 they opposed each other with intense vehemence. There is need then, for definition and delineation. The problem of clarification involves a reinterpretation of certain socialist ideologies and a more definite understanding of the forces which brought about the politicizing of them. For France, only one author made this latter topic the subject of a special study.1 However, he fell somewhat short of his goal, especially for the pre-18 48 period, the one with which this essay deals. The purpose of this study, there- fore, is to offer a more precise explanation concerning the origin of one of the currents of early socialist philosophy, called here Jacobin socialism. -

Proudhon, the First Liberal Socialist

Proudhon, the First Liberal Socialist Monique Canto-Sperber “Proudhon? He is a liberal masquerading as a socialist,” observed Pierre Leroux.1 Louis Blanc, in turn, strongly disapproved of the liberal orientation of Proudhon’s thought.2 Two such usages of the term “liberal” cannot fail to intrigue the historian. When we think of the abyss that came to separate the common understandings of liberalism and socialism in the thirty years that followed the appearance of the term socialisme, it is astonishing to see such a conjunction of the adjectives libéral and socialiste. The opportunity to present the work of Proudhon in a somewhat unusual light is provided by the desire to understand how this author could simultaneously embody two such opposing terms. The work of Pierre-Joseph Proudhon holds a singular place among those of French thinkers who were interested in the reform of society during the first half of the nineteenth century. What’s more, the thought of Proudhon is richly represented in the Gimon Collection held by the Stanford University Library. The works contained in the collection, which brings together extremely rare first editions, such as an exceptional collection of periodicals edited by Proudhon, provide an occasion to reflect upon the question of Proudhon’s liberal socialism. Socialism and liberalism are often presented as two political philosophies with opposite conceptions of man and of society. Liberals defend the primacy of the individual and the autonomy of human activities. They believe that private property is the best guarantee of personal liberty. Economic life must result, according to them, from the free interaction, without any intervention, of economic initiative and contracts brokered directly between employers and workers. -

XANARCHISM of Michael A

The Doctrine of XANARCHISM of Michael A. Bakuniry By Eugene Pyziur 9/5" a. The Marquette University Press Milwaukee 19JJ Wisconsin MARQUETTE SLAVIC STUDIES The Doctrine of Anarchism of Michael A. Bakunin y MABQUETTE SLAVIC STUDIES are published under the direction of the Slavic Institute of Marquette University. Edited by ROMAN SMAL-STOCKI Advisory Board ALFRED SOKOLNICKI CHRISTOPHER SPALATIN Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 55-12423 Copyright, 1955, Marquette University Press, Milwaukee, Wis. MANUFACTURED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA Preface The Slavic Institute will celebrate the 75th anniversary of its Alma Mater by initiating the publication of Marquette Slavic Studies. We would like to strengthen the knowledge of Slavic matters and problems in America through this special series of mono- graphs on Slavic nations, their history, culture, civilization, and their great personalities. Simultaneously we would like to culti- vate through original research, the Slavic heritage of more than twelve million of America's citizens. According to our anniversary motto, we dedicate the series to the "Pursuit of Truth to Make Men Free," and in this spirit we shall approach all Slavic nations, large and small, with a deep sense of their fundamental equality, disregarding all Slavic im- perialisms and colonialisms, and with a warm respect for their fine heritage, which has become a component part of our Ameri- can culture and civilization. The Editor Contents Chapter 1 BAKUNIN'S PERSONALITY 1 The course of his life. Contradictions within his character. Diverse judgments of his role and his achievements. Chapter 2 BAKUNIN AS A POLITICAL THINKER 15 Consensus that Bakunin did not contribute essentially to anarchist doctrine; basis for and inadequacy of this view. -

Crises in Early French Dictionaries and Encyclopaedias (1830-1840) Ludovic Frobert

Between progress and decline : crises in early French dictionaries and encyclopaedias (1830-1840) Ludovic Frobert To cite this version: Ludovic Frobert. Between progress and decline : crises in early French dictionaries and encyclopaedias (1830-1840). Besomi, Daniele. Crises and business cycles in economic dictionaries and encyclopaedias, Routledge, pp.167-176, 2012. halshs-00714949 HAL Id: halshs-00714949 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-00714949 Submitted on 23 Jun 2017 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. XI. Between progress and decline : crises in early French dictionaries and encyclopaedias (1830-1840) Ludovic Frobert CNRS/TRIANGLE Encyclopédie du dix-neuvième siècle, répertoire universel des sciences, des lettres et des arts, avec la biographie de tous les hommes célèbres, Paris : au bureau de "l'Encyclopédie du XIXe siècle" (1836-1853). Encyclopédie des gens du monde, répertoire universel des sciences, des lettres et des arts [Texte imprimé] : avec des notices sur les principales familles historiques et sur les personnages célèbres, morts et vivans, par une société de savans, de littérateurs et d'artistes, français et étrangers, Paris : Treuttel et Würtz, 1833-1844. Dictionnaire du commerce et des marchandises contenant tout ce qui concerne le commerce de terre et de mer, Paris, Guillaumin, 1839. -

Utopian Androgyny: Romantic Socialists Confront Individualism in July Monarchy France Naomi J

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Scholar Commons - Santa Clara University Santa Clara University Scholar Commons History College of Arts & Sciences 2003 Utopian Androgyny: Romantic Socialists Confront Individualism in July Monarchy France Naomi J. Andrews Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarcommons.scu.edu/history Part of the Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons, and the History Commons Recommended Citation Andrews, Naomi J. (2003). Utopian Androgyny: Romantic Socialists Confront Individualism in July Monarchy France. French Historical Studies 26.3 (2003) 437-457. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Arts & Sciences at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in History by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Naomi J. Andrews - Utopian Androgyny: Romantic Socialists Confront Individualism in July Monarchy France - French Historical Studies ... Copyright © 2003 by The Society for French Historical Studies. All rights reserved. French Historical Studies 26.3 (2003) 437-457 Utopian Androgyny: Romantic Socialists Confront Individualism in July Monarchy France Naomi J. Andrews The two sexes will be but one, according to the word of Christ; the great androgyne will be created; humanity will be woman and man, love and thought, tenderness and force, grace and energy. Abbé Constant In a certain respect, nineteenth-century intellectual and political history is the story of the liberal individual and his foes. From conservative Christian thinkers to Socialists to Communists, French intellectuals of the first part of the century were engaged in one long conversation about the individual and his (and later, her) rights, responsibilities, and relationship to society.