French Newspapers and Ephemera from the 1848 Revolution

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reinventar La Izquierda En El Siglo Xxi

Reinventar la izquierda en el siglo xxi José Luis Coraggio y Jean-Louis Laville (organizadores) Reinventar la izquierda en el siglo xxi Hacia un diálogo Norte-Sur Reinventar la izquierda en el siglo XXI : hacia un dialogo norte-sur / José Luis Coraggio ... [et.al.] ; coordinado por José Luis Coraggio y Jean-Louis Laville. - 1a ed. - Los Polvorines : Universidad Nacional de General Sarmiento, 2014. 548 p. ; 21x15 cm. ISBN 978-987-630-192-3 1. Teorías Polìticas. I. Coraggio, José Luis II. Coraggio, José Luis, coord. III. Laville, Jean-Louis, coord. CDD 320.1 Fecha de catalogación: 07/08/2014 © Universidad Nacional de General Sarmiento, 2014 J. M. Gutiérrez 1150, Los Polvorines (B1613GSX) Prov. de Buenos Aires, Argentina Tel.: (54 11) 4469-7578 [email protected] www.ungs.edu.ar/ediciones Traducción del inglés: Gabriela Ventureira. Traducción del francés: Marie Bardet con la colaboración de Carlos Pérez. Diseño de colección: Andrés Espinosa - Departamento de Publicaciones - UNGS / Alejandra Spinelli Corrección: Edit Marinozzi Hecho el depósito que marca la Ley 11723 Prohibida su reproducción total o parcial Derechos reservados Impreso en Docuprint S. A. Calle Taruarí 123 (C1071AAC) Ciudad de Buenos Aires, Argentina, en el mes de septiembre de 2014. Tirada: 400 ejemplares. Índice Reconocimientos .....................................................................................11 PRESENTACIÓN POR LA UNGS / Eduardo Rinesi ................................... 13 PRESENTACIÓN POR EL IAEN / Guillaume Long ....................................17 INTRODUCCION GENERAL / José Luis Coraggio y Jean-Louis Laville ..... 21 Otra política, otra economía, otras izquierdas / José Luis Coraggio ........ 35 Izquierda europea y proyecto emancipador / Jean-Louis Laville .............. 85 Mensajes a la izquierda de ayer y a la de hoy / Guy Bajoit ..................... -

General Index

SCIENCE & SOCIETY GENERAL INDEX VOLUMESI-XXV (1936�1961) Part I: Author, Subject and Title Part II: Books Reviewed SCIENCE & SOCIETY, INC. New York 1965 Copyright © 1965 by Science and Society, Inc. 30 East 20th Street, New York, N.Y. 10003 All Rights Reserved Printed in the United States of America Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 40-10163 �341 PREFACE The editors of Science & Society believe that this index to its contents during the first twenty-five years of publication deserves the uncustomary tribute of an editorial note, since it serves to remind us that Science & Society is theoldest publication extant devoted to the theory of Marxism. Indeed, with the single exception of that monument to German scholar ship, Die Neue Zeit (1883-1923), it is the longest-lived Marxist theoretical journal in the world, and this despite the enormous difficulties under which Science & Society has always been published. The editors, therefore, take this opportunity to reaffirm their inten tion of making Science & Society a forum for the best Marxist scholarship, and their hope that the preface to some future edition of its index will no longer need to note the exception of Die N eue Zeit. We think that those who, using this index, rediscover the great variety of subjects treated and the quality of critical scholarship represented, will agree with us that it is a bibliographic tool of real value to all scholars, but truly invaluable to Marxists. Finally, the editors of Science & Society wish to express their deep gratitude to the Louis M. Rabinowitz Foundation whose generous grant made the publication of this index possible. -

Individualism and Socialism

INDIVIDUALISM AND SOCIALISM. (1834) By Pierre Leroux AND OTHER WRITINGS ON THE DOCTRINE OF HUMANITY INDIVIDUALISM AND SOCIALISM. (1834.—After the massacres on the Rue Transnonain.) At times, even the most resolute hearts, those most firmly focused on the sacred beliefs of progress, lose courage and feel themselves full of disgust with the present. In the 16th century, when we murdered in our civil wars, it was in the name of God and with a crucifix in hand; it was a question of the most sacred things, of things which, once they have secured our conviction and our faith, dominate our natures so legitimately that there is nothing to do but obey, and even our most precious prerogatives are voluntarily sacrificed to the divine will. In the name of what principle do we today send off, by telegraph, pitiless orders, and transform proletarian soldiers into the executioners of their own class? Why has our era seen cruelties which recall St. Bartholemew? Why have men been fanaticized to the point of making them slaughter the elderly, women, and children in cold blood? Why has the Seine rolled with murders which recall the arquebuscades from the windows of the Louvre? It is not in the name of God and eternal salvation that these things are done. It is in the name of material interests. Our century is, it seems, quite vile, and we have degenerated even from the crimes of our fathers. To kill in the manner of Charles IX or Torquemada, in the name of faith and the Church, because one believes that God desires it, because one has a fanatic spirit, exalted by the fear of hell and the hope of paradise, is still to have some grandeur and some generosity in one's crime. -

1. the Heritage of Modern Socialist Ideas

Section XVI: Developments in Socialism, Contemporary Civilization (Ideas and Institutions 1848-1914 of Western Man) 1958 1. The eH ritage of Modern Socialist Ideas Robert L. Bloom Gettysburg College Basil L. Crapster Gettysburg College Harold L. Dunkelberger Gettysburg College See next page for additional authors Follow this and additional works at: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/contemporary_sec16 Part of the Models and Methods Commons, and the Sociology Commons Share feedback about the accessibility of this item. Bloom, Robert L. et al. "1. The eH ritage of Modern Socialist Ideas. Pt. XVI: Developments in Socialism, (1848-1914)." Ideas and Institutions of Western Man (Gettysburg College, 1958), 2-6. This is the publisher's version of the work. This publication appears in Gettysburg College's institutional repository by permission of the copyright owner for personal use, not for redistribution. Cupola permanent link: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/ contemporary_sec16/2 This open access book chapter is brought to you by The uC pola: Scholarship at Gettysburg College. It has been accepted for inclusion by an authorized administrator of The uC pola. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1. The eH ritage of Modern Socialist Ideas Abstract Of the total heritage which gave birth to modern socialism, brief attention may be given to certain of the predecessors of Karl Marx. Although some now are saved from obscurity only by the diligence of interested historians, others generated powerful ideas still not extinguished today. Together they created an amorphous body of thought from which Marx freelv drew. Consequently, an understanding of the varieties of later socialism, and specifically of Marx, requires a brief survey of these men. -

H-France Review Vol. 20 (October 2020), No. 176 Julia Nicholls

H-France Review Volume 20 (2020) Page 1 H-France Review Vol. 20 (October 2020), No. 176 Julia Nicholls, Revolutionary Thought after the Paris Commune, 1871-1885. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2019. vii + 309 pp. Bibliography and index. $99.99 U.S. (cl). ISBN 9781108499262; $32.99 U.S. (pb). ISBN 9781108713344; $80.00 U.S. (eb). ISBN 9781108600002. Review by Julian Bourg, Boston College. Revision is the historian’s stock-in-trade. Explanations of the past do not endure. Interpretations change as constantly altering circumstances shift vantage points, and even new evidence comes into view more often as a consequence than as a cause of such temporal parallax. In another way, however, in recent decades revisionism has become a default mode of historical writing. To take classic examples from contemporary French historical studies, one thinks of post-colonialism successfully decentering the metropole, François Furet overcoming Marxist interpretations of the French Revolution, and Robert Faurisson’s miserable négationnisme trying to abandon the facts of the Shoah. The extremely different normative consequences of such debates are clear, make no mistake, but so too is a certain historiographical pattern: the move to challenge and substitute prevailing views. The gesture of the hand that turns the kaleidoscope’s viewfinder, offering up endlessly combining and dispersing shards of colored glass, is itself repetitive. Historical revisionism can thus seem both a regular gambit--knotting historical writing to its present--and also a seemingly expected, even obligatory move within the “ironist’s cage” of the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries.[1] Julia Nicholls has revised one of the most tired stereotypes of the early Third Republic: that in the wake of the Commune’s defeat in 1871, little transpired by way of revolutionary thought in France until Marxist orthodoxy ascended in the mid-to-late 1880s. -

Blanqui’S Note Nov

Biliana Kassabova History of Political Thought Workshop December 4, 2017 Blanqui’s note Nov. 23, 1848 Blanqui between Myth and Archives: Revolution, Dictatorship, and Education This piece, very much a work in progress, aims to make sense of the revolutionary ideas and actions of Louis-Auguste Blanqui. It complicates our ideas of political thought regarding revolution in the nineteenth century, by arguing that the binary of centralized versus popular revolution needs to be revised. It is part of a larger project on concepts of revolutionary leadership in France from the French Revolution of 1789 until the Paris Commune of 1871. Within this historical trajectory, Blanqui is an interpreter of 18th century ideas into 19th century contexts, a political thinker and actor who plays a key role in the various reformulations of the revolutionary tradition. 1848 does not enjoy a stellar reputation among historians of France. The revolution of February that year saw the overthrow of the last king of France, followed by the establishment of a new French republic. This republic, however, lasted for only three years, brought little and short-lived social change, remained rather conservative, though was also laden with bitter parliamentary strife, and ended through a coup d’état that inaugurated a new authoritarian régime, a Second Empire with Napoleon III at its head. To add insult to injury, even the attempts at establishing a viable parliamentary republican system were famously seen by political observers and participants from 2 almost all parts of the political spectrum as derivative, incompetent, and worse yet – laughable. “There have been more mischievous revolutionaries than those of 1848, but I doubt if there have been any stupider,”1 quipped Alexis de Tocqueville in his posthumously published Recollections. -

Agape, Philia and Eros Anca Simitopol Thesis Submi

Ideas of Community in the Thought of Pierre Leroux and of Feodor Dostoevsky: Agape , Philia and Eros Anca Simitopol Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the PhD degree in Political Science Supervisor: Gilles Labelle Political Studies Social Sciences University of Ottawa ©Anca Simitopol, Ottawa, Canada, 2012 Contents ABSTRACT ……………………………………………………………………… iv INTRODUCTION ……………………………………………………………… 1 CHAPTER ONE Two Critics of “Possessive Individualism” ………………………………….. 11 1.1. Introduction ……………………………………………………………... 11 1.2. Leroux as a liberal …………………………………………………......... 27 1.3. Leroux’s anthropology: Liberté, Égalité, Fraternité …………………... 37 1.4. Division of society, division of the self and eclecticism ………………... 42 1.5. Freedom according to Leroux …………………………………………... 47 1.6. Property according to Leroux …………………………………………… 58 1.7. Dostoevsky as political thinker ………………………………………….. 68 1.8. The poor and the ontological meaning of capitalism ………………….. 70 1.9. “Possessive Individualism” in Russia …………………………………… 82 1.10. From individualism to the revolutionary affirmation of the will-to-power 1.10.1. Raskolnikov ………………………………………………….. 93 1.10.2. The case of “The possessed” ………………………………... 98 1.11. Conclusion …………………………………………………………… 105 CHAPTER TWO Varieties of Socialism and of Utopia ………………………………………. 115 2.1. Introduction ...………………………………………………………… 115 2.2. Dostoevsky’s critique of socialism: “Shigalovism” …………………. 130 2.3. Leroux’s critique of Fourier’s socialism ……………………………. 144 2.4. Introduction to utopia ………………………………………………... 149 2.5. Transformation of utopia in the 19 th century ……………………….. 158 2.6. Saint-Simon: oscillation between transcendence and immanence .... 171 2.7. The Saint-Simonian School: utopia transformed into political program …………………………………………………….. 180 2.8. The Grand Inquisitor and the incompatibility between freedom and unity ……………………………………………………. 193 2.9. Dostoevsky: a dialogical utopia ……………………………………… 207 2.10. -

Economic, Social and Demographic Thought in the Xixth Century

Yves Charbit Economic, Social and Demographic Thought in the XIXth Century The Population Debate from Malthus to Marx 123 Prof. Yves Charbit Universite´ Paris Descartes UMR CEPED (Universite´ Paris Descartes-INED-IRD) 75006 Paris France ISBN 978-1-4020-9959-5 e-ISBN 978-1-4020-9960-1 DOI 10.1007/978-1-4020-9960-1 Library of Congress Control Number: 2009920976 c Springer Science+Business Media B.V. 2009 No part of this work may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, microfilming recording or otherwise, without written permission from the Publisher, with the exception of any material supplied specificall for the purpose of being entered and executed on a computer system, for exclusive use by the purchaser of the work. Printed on acid-free paper 987654321 springer.com Contents 1 The Population Controversy and Beyond .......................... 1 Theoretical Progress and Affiliation . ............................ 2 Demographic Theory and Economic Theory . ..................... 4 Demographic Doctrines and Ideology . ............................ 5 Interpreting Theories and Doctrines ................................ 6 2 Population, Economic Growth and Religion: Malthus as a Populationist .......................... 9 The Central Concepts . ........................................... 13 The First Model: Regulation by Mortality . ..................... 15 The First Model: Scandinavian Countries . ..................... 16 The Reform of the Poor Laws in England . -

ACTA UNIVERSITATIS UPSALIENSIS Skrifter Utgivna Av Statsvetenskapliga Föreningen I Uppsala 196

ACTA UNIVERSITATIS UPSALIENSIS Skrifter utgivna av Statsvetenskapliga föreningen i Uppsala 196 Svante Nycander The History of Western Liberalism Front cover portraits: Thomas Jefferson, Baruch de Spinoza, Adam Smith, Alexis de Tocqueville, Oliver Wendell Holmes, Joseph Schumpeter, Woodrow Wilson, Niccoló Machiavelli, Karl Staaff, John Stuart Mill, François-Marie Arouet dit Voltaire, Mary Wollstonecraft, John Locke, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Immanuel Kant, Ludwig Joseph Brentano, John Dewey, Wilhelm von Humboldt, Charles-Louis de Secondat Montesquieu, Ayn Rand © Svante Nycander 2016 English translation: Peter Mayers Published in Swedish as Liberalismens idéhistoria. Frihet och modernitet © Svante Nycander and SNS Förlag 2009 Second edition 2013 © Svante Nycander and Studentlitteratur ISSN 0346-7538 ISBN 978-91-554-9569-5 Printed in Sweden by TMG Tabergs AB, 2016 Contents Preface ....................................................................................................... 11 1. Concepts of Freedom before the French Revolution .............. 13 Rights and Liberties under Feudalism and Absolutism ......................... 14 New Ways of Thinking in the Renaissance ........................................... 16 Calvinism and Civil Society .................................................................. 18 Reason as a Gift from God .................................................................... 21 The First Philosopher to Be Both Liberal and Democratic ................... 23 Political Models during the Enlightenment .......................................... -

From Marx to Ecosocialism

SOCIALISMANDECOLOGY From Marx to Ecosocialism* ByMichaelLöwy Since the industrial revolution, capitalist societies (and more recently,thelatebureaucraticsocietiesofEasternEurope)havebeen characterized by an ever-growing rationalization. Following Max Weber,wecandistinguishthreecloselyrelatedaspectsofthis: 1)Zweckrationalitat,ortherationality-of-ends,thatis,theutilizationof rational means to attain objectives that are not at all rational themselves.Bureaucracyistheideal-typicalinstitutionalexpressionof this pattern. This is what the Frankfurt School referred to as instrumentalrationality,atypeof ratio compatiblewith themost monstroussubstantiveirrationalities—therational-bureaucraticadmin- istrationofgenocide,forinstance,totakethelimitingcase.Butapart fromsuchextremes,asErnestMandelhaspointedout,thecombination of partial rationality with overall irrationality is intrinsic to the “normal”functioningofthecapitalisteconomyanditsbureaucratic institutions.1 2)Thedifferentiationandautonomizationofdomains,resultinginthe separationoftheeconomic,social,political,andculturalspheres.The marketeconomybecomesaself-regulatingsystemthatisnolonger “embedded”inthesociety(tousePolanyi’sfamousexpression),thereby escapingsocial,moral,orpoliticalcontrol. 3)Rechenhaftigkeit,orthespiritofrationalcalculationandthegeneral tendency to quantification. This tendency finds its most direct *TranslatedbyK.PMosely.Quoteshavebeentranslatedbutthecitedtexts aretheoriginals. 1Ernest Mandel, Power and Money: A Marxist Theory of Bureaucracy (London:Verso,1992),p.182. CNS,13(1),March,2002 -

Enzo Traverso. Left-Wing Melancholia: Marxism, History, and Memory

Enzo Traverso. Left-Wing Melancholia: Marxism, History, and Memory. New York: Columbia University Press, 2016. Pp. 289 (cloth). Reviewed by Mark Steven, UNSW Sydney How else to look back on the previous 150 years from the standpoint of the left than with a sense of melancholia? We have with us now, exactly one century after the Bolshevik Revolution, a well-formed constellation of persons and objects and ideas from which a melancholic structure of feeling emanates. Its brightest stars belong to the martyrs: Louis Auguste Blanqui (-1881), Rosa Luxemburg (-1919), Emiliano Zapata (also -1919), Leon Trotsky (-1940), Szmul Zygielbojm (-1943), Che Guevara (-1967), Ulrike Meinhof (-1976), and more. Its epic has been sung in the verse of Bertolt Brecht, Muriel Rukeyser, and César Vallejo, and told in the prose of Andrei Platonov, Roberto Bolaño, and David Peace. Its visualization begins with Gustave Courbet’s Burial at Ornans, reaches through El Lissitzky’s constructivist tribute to the murdered founder of the Spartakusbund, only to appear and reappear in the cinema of Luchino Visconti, Theo Angelopoulos, Aleksandr Sokurov, and Patricio Guzmán. And if, through all of this, left-wing melancholia has attained to a single totalizing form—if our melancholic constellation were to gravitate into the black hole that embodies this entire tradition at once and in itself—then that form would look something like the filmic elegies orchestrated by László Krasznahorkai and Béla Tarr—“films of maturity,” writes Jacques Rancière, accompanying the collapse of the Soviet system and its disenchanting capitalist consequences, when the censure of the market has taken over for that of the State: darker and darker films, in which politics is reduced to manipulation, the social promise to a swindle, and the collective to the brutal horde.1 While left-wing melancholia has had its share of theorists in the recent past— any respectable list of whom would have to include Wendy Brown, T. -

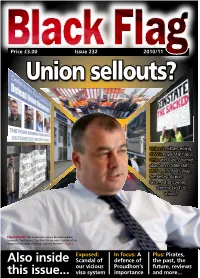

Also Inside This Issue

PricePrice £3.00 £3.00 IssueIssue 232 229 Mid 2010/11 2009 Union sellouts? Unison’s militant exiling, CWU’s Royal Mail fiasco, Unite and Gate Gourmet, abandoned Mitie staff, NUT and St Paul’s Way, the Belfast Airport farce... what’s wrong with the big TUC unions? Figurehead: TUC general secretary Brendan Barber lambasts “bad bosses,” but do the member unions of his organisation really stand up when it matters? Page 7 Exposed: In focus: A Plus: Pirates, Also inside Scandal of defence of the past, the our vicious Proudhon’s future, reviews this issue... visa system importance and more... Editorial Welcome to issue 232 of Black Flag, which coincides once again with the annual London Anarchist Bookfair, the largest and longest-running event of its kind in the world. Now that this issue is the 7th published by the “new” collective we can safely drop the “new” bit! We believe that we have come a long way with Black Flag. As a very small collective we have managed to publish and sustain a consistent and high-quality, twice yearly, class- struggle anarchist publication on a shoe-string budget and limited personnel. Before proceeding further, we would like to make our usual appeal for more people to get involved with the editorial group. The more people who get involved, the more Black Flag will grow with increased frequency and wider distribution etc. This issue includes our usual eclectic mix of libertarian-left theory, history, debate, analysis and reportage. Additionally, this issue is again somewhat of an anniversary issue, which acknowledges two significant events.