Russian Language Media in Estonia 1990–2012

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Levi TV Kanalid

levikom.ee 1213 Paksenduse (bold) ja punase teksti tähistusega telekanaleid on võimalik järelvaadata 7 päeva täies mahus (järelvaatamise teenus on eraldi kuutasu eest)! Telekanalite Levi TV Paras Levi TV Priima Levi TV Ekstra sisaldumine pakettides: - Põhikanaleid 33 kanalit 63 kanalit 69 kanalit - Muid kanaleid 5 kanalit 5 kanalit 10 kanalit KÕIK KOKKU: 38 telekanalit 68 telekanalit 79 telekanalit Eesti telekanalid: ETV ✓ ✓ ✓ ETV2 ✓ ✓ ✓ Kanal 2 ✓ ✓ ✓ TV3 ✓ ✓ ✓ TV6 ✓ ✓ ✓ Kanal 11 ✓ ✓ ✓ Kanal 12 ✓ ✓ ✓ Alo TV ✓ ✓ ✓ Taevas TV7 ✓ ✓ ✓ Eesti Kanal ✓ ✓ ✓ Eesti Kanal Pluss ✓ ✓ ✓ (11 kanalit) (11 kanalit) (11 kanalit) Eesti kanalid HD formaadis (duplikaadina): ETV HD ✓ ✓ ✓ ETV2 HD ✓ ✓ ✓ Kanal 2 HD ✓ ✓ ✓ Kanal 11 HD ✓ ✓ ✓ Kanal 12 HD ✓ ✓ ✓ TV3 HD ✓ TV6 HD ✓ (5 kanalit) (5 kanalit) (5 kanalit) Laste ja noorte telekanalid: Kidzone ✓ ✓ ✓ Kidzone+ HD ✓ ✓ Smartzone HD ✓ ✓ KiKa HD ✓ ✓ Nick JR ✓ ✓ Nickelodeon ✓ ✓ TEL 1213 TEL +372 684 0678 Levikom Eesti OÜ Pärnu mnt 139C, 11317 Tallinn [email protected] | levikom.ee Pingviniukas ✓ ✓ ✓ Multimania ✓ ✓ ✓ Mamontjonok ✓ ✓ ✓ (4 kanalit) (9 kanalit) (9 kanalit) Filmide ja sarjade telekanalid: Epic Drama HD ✓ ✓ ✓ TLC ✓ ✓ ✓ Sony Channel HD ✓ ✓ Sony Turbo HD ✓ ✓ FOX ✓ ✓ FOX Life ✓ ✓ Filmzone ✓ ✓ Filmzone+ HD ✓ ✓ Kino 24 ✓ ✓ ✓ Pro100TV ✓ ✓ ✓ Dom Kino ✓ ✓ ✓ (5 kanalit) (9 kanalit) (11 kanalit) Sporditeemalised telekanalid: Eurosport 1 HD ✓ ✓ ✓ Eurosport 2 HD ✓ ✓ ✓ Setanta Sports HD ✓ ✓ ✓ Fuel TV HD ✓ ✓ Nautical Channel ✓ ✓ (3 kanalit) (5 kanalit) (5 kanalit) Teaduse, looduse ja tõsielu teemalised telekanalid: Discovery -

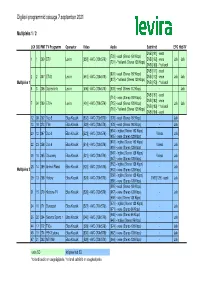

Levira DTT Programmid 09.08.21.Xlsx

Digilevi programmid seisuga 7.september 2021 Multipleks 1 / 2 LCN SID PMT TV Programm Operaator Video Audio Subtiitrid EPG HbbTV DVB [161] - eesti [730] - eesti (Stereo 192 Kbps) 1 1 290 ETV Levira [550] - AVC (720x576i) DVB [162] - vene Jah Jah [731] - *hollandi (Stereo 128 Kbps) DVB [163] - *hollandi DVB [171] - eesti [806] - eesti (Stereo 192 Kbps) 2 2 307 ETV2 Levira [561] - AVC (720x576i) DVB [172] - vene Jah Jah [807] - *hollandi (Stereo 128 Kbps) Multipleks 1 DVB [173] - *hollandi 6 3 206 Digilevi info Levira [506] - AVC (720x576i) [603] - eesti (Stereo 112 Kbps) - - Jah DVB [181] - eesti [714] - vene (Stereo 192 Kbps) DVB [182] - vene 7 34 209 ETV+ Levira [401] - AVC (720x576i) [715] - eesti (Stereo 128 Kbps) Jah Jah DVB [183] -* hollandi [716] - *hollandi (Stereo 128 Kbps) DVB [184] - eesti 12 38 202 Duo 5 Elisa Klassik [502] - AVC (720x576i) [605] - eesti (Stereo 192 Kbps) - Jah 13 18 273 TV6 Elisa Klassik [529] - AVC (720x576i) [678] - eesti (Stereo 192 Kbps) - Jah [654] - inglise (Stereo 192 Kbps) 20 12 267 Duo 3 Elisa Klassik [523] - AVC (720x576i) Videos Jah [655] - vene (Stereo 128 Kbps) [618] - inglise (Stereo 192 Kbps) 22 23 258 Duo 6 Elisa Klassik [514] - AVC (720x576i) Videos Jah [619] - vene (Stereo 128 Kbps) [646] - inglise (Stereo 128 Kbps) 26 10 265 Discovery Elisa Klassik [521] - AVC (720x576i) Videos Jah [647] - vene (Stereo 128 Kbps) [662] - inglise (Stereo 128 Kbps) 28 14 269 Animal Planet Elisa Klassik [525] - AVC (720x576i) - Jah Multipleks 2 [663] - vene (Stereo 128 Kbps) [658] - inglise (Stereo 128 Kbps) -

Russian Language Media in Estonia 1990–2012

This is a self-archived version of an original article. This version may differ from the original in pagination and typographic details. Author(s): Jõesaar, Andres; Rannu, Salme; Jufereva, Maria Title: Media for the minorities : Russian language media in Estonia 1990-2012 Year: 2013 Version: Published version Copyright: © Vytauto Didziojo universitetas, 2013 Rights: In Copyright Rights url: http://rightsstatements.org/page/InC/1.0/?language=en Please cite the original version: Jõesaar, A., Rannu, S., & Jufereva, M. (2013). Media for the minorities : Russian language media in Estonia 1990-2012. Media transformations, 9(9), 118-154. https://doi.org/10.7220/2029- 865X.09.07 ISSN 2029-865X 118 doi://10.7220/2029-865X.09.07 MEDIA FOR THE MINORITIES: RUSSIAN LANGUAGE MEDIA IN ESTONIA 1990–2012 Andres JÕESAAR [email protected] PhD, Associate Professor Baltic Film and Media School Tallinn University Head of Media Research Estonian Public Broadcasting Tallinn, Estonia Salme RANNU [email protected] Analyst Estonian Public Broadcasting Tallinn, Estonia Maria JUFEREVA [email protected] PhD Candidate University of Jyväskylä Jyväskylä, Finlanda ABSTRACT: This article aims to explore the ways in which Estonian public broa- dcasting tackles one specific media service sphere; how television programmes for language minorities are created in a small country, how economics and European Union media policy have influenced this processes. The article highlights major ten- sions, namely between Estonian and Russian media outlets, Estonian and Russian speakers within Estonia and the EU and Estonia concerning the role of public ser- vice broadcasting (PSB). For research McQuail’s (2010) theoretical framework of media institutions’ influencers – politics, technology and economics – is used. -

Generational Use of News Media in Estonia

Generational Use of News Media in Estonia Contemporary media research highlights the importance of empirically analysing the relationships between media and age; changing user patterns over the life course; and generational experiences within media discourse beyond the widely-hyped buzz terms such as the ‘digital natives’, ‘Google generation’, etc. The Generational Use doctoral thesis seeks to define the ‘repertoires’ of news media that different generations use to obtain topical information and create of News Media their ‘media space’. The thesis contributes to the development of in Estonia a framework within which to analyse generational features in news audiences by putting the main focus on the cultural view of generations. This perspective was first introduced by Karl Mannheim in 1928. Departing from his legacy, generations can be better conceived of as social formations that are built on self- identification, rather than equally distributed cohorts. With the purpose of discussing the emergence of various ‘audiencing’ patterns from the perspectives of age, life course and generational identity, the thesis centres on Estonia – a post-Soviet Baltic state – as an empirical example of a transforming society with a dynamic media landscape that is witnessing the expanding impact of new media and a shift to digitisation, which should have consequences for the process of ‘generationing’. The thesis is based on data from nationally representative cross- section surveys on media use and media attitudes (conducted 2002–2012). In addition to that focus group discussions are used to map similarities and differences between five generation cohorts born 1932–1997 with regard to the access and use of established news media, thematic preferences and spatial orientations of Signe Opermann Signe Opermann media use, and a discursive approach to news formats. -

Department of Social Research University of Helsinki Finland

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Helsingin yliopiston digitaalinen arkisto Department of Social Research University of Helsinki Finland NORMATIVE STORIES OF THE FORMATIVE MOMENT CONSTRUCTION OF ESTONIAN NATIONAL IDENTITY IN POSTIMEES DURING THE EU ACCESSION PROCESS Sigrid Kaasik-Krogerus ACADEMIC DISSERTATION To be presented, with the permission of the Faculty of Social Sciences of the University of Helsinki, for public examination in lecture room 10, University main building, on 12 February 2016, at 12 noon. Helsinki 2016 Publications of the Faculty of Social Sciences 1 (2016) Media and Communication Studies © Sigrid Kaasik-Krogerus Cover: Riikka Hyypiä & Hanna Sario Distribution and Sales: Unigrafia Bookstore http://kirjakauppa.unigrafia.fi/ [email protected] PL 4 (Vuorikatu 3 A) 00014 Helsingin yliopisto ISSN 2343-273X (Print) ISSN 2343-2748 (Online) ISBN 978-951-51-1047-3 (Paperback) ISBN 978-951-51-1048-0 (PDF) Unigrafia, Helsinki 2016 ABSTRACT This longitudinal research analyzes the construction of Estonian national identity in the country’s largest and oldest daily newspaper Postimees in relation to the European Union (EU) in the course of Estonia’s EU accession process 1997-2003. I combine media studies with political science, EU studies and nationalism studies to scrutinize this period as an example of a ‘formative moment’. During this formative moment the EU became ‘the new official Other’ in relation to which a new temporary community, Estonia as a candidate country, was ‘imagined’ in the paper. The study is based on the assumption that national identity as a normative process of making a distinction between us and Others occurs in societal texts, such as the media. -

Television Across Europe

media-incovers-0902.qxp 9/3/2005 12:44 PM Page 4 OPEN SOCIETY INSTITUTE EU MONITORING AND ADVOCACY PROGRAM NETWORK MEDIA PROGRAM ALBANIA BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA BULGARIA Television CROATIA across Europe: CZECH REPUBLIC ESTONIA FRANCE regulation, policy GERMANY HUNGARY and independence ITALY LATVIA LITHUANIA Summary POLAND REPUBLIC OF MACEDONIA ROMANIA SERBIA SLOVAKIA SLOVENIA TURKEY UNITED KINGDOM Monitoring Reports 2005 Published by OPEN SOCIETY INSTITUTE Október 6. u. 12. H-1051 Budapest Hungary 400 West 59th Street New York, NY 10019 USA © OSI/EU Monitoring and Advocacy Program, 2005 All rights reserved. TM and Copyright © 2005 Open Society Institute EU MONITORING AND ADVOCACY PROGRAM Október 6. u. 12. H-1051 Budapest Hungary Website <www.eumap.org> ISBN: 1-891385-35-6 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data. A CIP catalog record for this book is available upon request. Copies of the book can be ordered from the EU Monitoring and Advocacy Program <[email protected]> Printed in Gyoma, Hungary, 2005 Design & Layout by Q.E.D. Publishing TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Contents Acknowledgements ........................................................ 5 Preface ........................................................................... 9 Foreword ..................................................................... 11 Overview ..................................................................... 13 Albania ............................................................... 185 Bosnia and Herzegovina ...................................... 193 -

Television Beyond and Across the Iron Curtain

Television Beyond and Across the Iron Curtain Television Beyond and Across the Iron Curtain Edited by Kirsten Bönker, Julia Obertreis and Sven Grampp Television Beyond and Across the Iron Curtain Edited by Kirsten Bönker, Julia Obertreis and Sven Grampp This book first published 2016 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2016 by Kirsten Bönker, Julia Obertreis, Sven Grampp and contributors All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-4438-9740-X ISBN (13): 978-1-4438-9740-2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ............................................................................................... vii Kirsten Bönker and Julia Obertreis I. Transnational Perspectives and Media Events Chapter One ................................................................................................. 2 Looking East–Watching West? On the Asymmetrical Interdependencies of Cold War European Communication Spaces Andreas Fickers Chapter Two .............................................................................................. 25 Campaigning Against West Germany: East German Television Coverage of the Eichmann Trial Judith Keilbach Chapter -

Digital Journalism: Making News, Breaking News

MAPPING DIGITAL MEDIA: GLOBAL FINDINGS DIGITAL JOURNALISM: MAKING NEWS, BREAKING NEWS Mapping Digital Media is a project of the Open Society Program on Independent Journalism and the Open Society Information Program Th e project assesses the global opportunities and risks that are created for media by the switch- over from analog broadcasting to digital broadcasting; the growth of new media platforms as sources of news; and the convergence of traditional broadcasting with telecommunications. Th ese changes redefi ne the ways that media can operate sustainably while staying true to values of pluralism and diversity, transparency and accountability, editorial independence, freedom of expression and information, public service, and high professional standards. Th e project, which examines the changes in-depth, builds bridges between researchers and policymakers, activists, academics and standard-setters. It also builds policy capacity in countries where this is less developed, encouraging stakeholders to participate in and infl uence change. At the same time, this research creates a knowledge base, laying foundations for advocacy work, building capacity and enhancing debate. Covering 56 countries, the project examines how these changes aff ect the core democratic service that any media system should provide—news about political, economic and social aff airs. Th e MDM Country Reports are produced by local researchers and partner organizations in each country. Cumulatively, these reports provide a unique resource on the democratic role of digital media. In addition to the country reports, research papers on a range of topics related to digital media have been published as the MDM Reference Series. Th ese publications are all available at http://www.opensocietyfoundations.org/projects/mapping-digital-media. -

Elisa Elamus Ja Elisa Klassik Kanalipaketid Kanalid Seisuga 25.09.2021

Elisa Elamus ja Elisa Klassik kanalipaketid kanalid seisuga 25.09.2021 XL/XLK 99 telekanalit + 7 HD kanalit L/LK 99 telekanalit M/MK 61 telekanalit S/SK 40 telekanalit PROGRAMM KANAL AUDIO SUBTIITRID PROGRAMM KANAL AUDIO SUBTIITRID ETV 1 EST 3+ 66 RUS Kanal 2 2 EST STS 71 RUS TV3 3 EST Dom kino 87 RUS ETV2 4 EST TNT4 90 RUS TV6 5 EST TNT 93 RUS Duo4 6 EST Pjatnitsa 104 RUS Duo5 7 EST Kinokomedia HD 126 RUS Elisa 14 EST Eesti Kanal 150 EST Cartoon Network 17 ENG; RUS Meeleolukanal HD 300 EST KidZone TV 20 EST; RUS Euronews 704 RUS Euronews HD 21 ENG 3+ HD 931 RUS CNBC Europe 32 ENG TV6 HD 932 EST ALO TV 46 EST TV3 HD 933 EST MyHits HD 47 EST Duo7 HD 934 RUS Deutsche Welle 56 ENG Duo5 HD 935 EST ETV+ 59 RUS Duo4 HD 936 EST PBK 60 RUS Kanal 2 HD 937 EST RTR-Planeta 61 RUS ETV+ HD 938 RUS REN TV Estonia 62 RUS ETV2 HD 939 EST NTV Mir 63 RUS ETV HD 940 EST Fox Life 8 ENG; RUS EST Discovery Channel 37 ENG; RUS EST Fox 9 ENG; RUS EST BBC Earth HD 44 ENG-DD Duo3 10 ENG; RUS EST VH 1 48 ENG TLC 15 ENG; RUS EST TV 7 57 EST Nickelodeon 18 ENG; EST; RUS Orsent TV 69 RUS CNN 22 ENG TVN 70 RUS BBC World News 23 ENG 1+2 72 RUS Bloomberg TV 24 ENG Eurosport 1 HD 905 ENG; ENG-DD; RUS Eurosport 1 28 ENG; RUS Duo3 HD 917 ENG; RUS EST Viasat History 33 ENG; RUS EST; FIN; LAT Viasat History HD 919 ENG; RUS EST; FIN History 35 ENG; RUS EST Duo6 11 ENG; RUS EST Eurochannel HD 52 ENG EST FilmZone 12 ENG; RUS EST Life TV 58 RUS FilmZone+ 13 ENG; RUS EST TV XXI 67 RUS AMC 16 ENG; RUS Kanal Ju 73 RUS Pingviniukas 19 EST; RUS 24 Kanal 74 UKR HGTV HD 27 ENG EST Belarus -

The Võru Language in Estonia: an Overview of a Language in Context

Working Papers in European Language Diversity 4 Kadri Koreinik The Võru language in Estonia: An Overview of a Language in Context Mainz Helsinki Wien Tartu Mariehamn Oulu Maribor Working Papers in European Language Diversity is a peer-reviewed online publication series of the research project ELDIA, serving as an outlet for preliminary research findings, individual case studies, background and spin-off research. Editor-in-Chief Johanna Laakso (Wien) Editorial Board Kari Djerf (Helsinki), Riho Grünthal (Helsinki), Anna Kolláth (Maribor), Helle Metslang (Tartu), Karl Pajusalu (Tartu), Anneli Sarhimaa (Mainz), Sia Spiliopoulou Åkermark (Mariehamn), Helena Sulkala (Oulu), Reetta Toivanen (Helsinki) Publisher Research consortium ELDIA c/o Prof. Dr. Anneli Sarhimaa Northern European and Baltic Languages and Cultures (SNEB) Johannes Gutenberg-Universität Mainz Jakob-Welder-Weg 18 (Philosophicum) D-55099 Mainz, Germany Contact: [email protected] © European Language Diversity for All (ELDIA) ELDIA is an international research project funded by the European Commission. The views expressed in the Working Papers in European Language Diversity are the sole responsibility of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the European Commission. All contents of the Working Papers in European Language Diversity are subject to the Austrian copyright law. The contents may be used exclusively for private, non-commercial purposes. Regarding any further uses of the Working Papers in European Language Diversity, please contact the publisher. ISSN 2192-2403 Working Papers in European Language Diversity 4 During the initial stage of the research project ELDIA (European Language Diversity for All) in 2010, "structured context analyses" of each speaker community at issue were prepared. -

TARTU UNIVERSITY Faculty of Social Sciences and Education Institute of Government and Politics Centre for Baltic Sea Region Studies

TARTU UNIVERSITY Faculty of Social Sciences and Education Institute of Government and Politics Centre for Baltic Sea Region Studies Kevin Axe FINNISH ADS, ESTONIAN TVS: EXTERNAL CULTURAL ROOTS OF ELITE NEOLIBERAL CONSENSUS IN TRANSITIONAL ESTONIA Master’s thesis Supervisors: Dr. Andres Kasekamp and Dr. Vello Pettai Tartu, 2015 This thesis conforms to the requirements for a Master’s thesis. ……………………………………………….……….. (Signature of a supervisor and date) ……………………………………………….………... (Signature of a supervisor and date) Submitted for defense …………………………………. (Date) This thesis is 24,989 words in length. I have written this Master’s thesis independently. All ideas and data taken from other authors or other sources have been fully referenced. I agree to publish my thesis on the University of Tartu’s DSpace and on the webpage of its Centre for Baltic Studies. …………………………………………………………. (Signature of the author and date) 2 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to start by thanking my supervisors, Dr. Andres Kasekamp and Dr. Vello Pettai, for their patience, guidance, and recommendations. I am also very grateful to my interviewees, who not only took time from their busy lives to meet with me for long conversations in a foreign language, but gave me the detailed, thoughtful answers, and occasionally sources and recommendations, that allowed this project to exist. Moreover, I would like to thank Dr. Heiko Pääbo for his seminars, and both him and Siiri Maimets for their help in helping me navigate academia and attain my degree over the past two years, as well as Dr. Viktor Trasberg, my initial supervisor, for help and advice when this was a very different project. -

Is the Role of Public Service Media in Estonia Changing?

Commentary Is the Role of Public Service Media in Estonia Changing? ANDRES JÕESAAR, Tallinn University, Estonia; email: [email protected] RAGNE KÕUTS-KLEMM, University of Tartu, Estonia; email: [email protected] 96 10.2478/bsmr-2019-0006 BALTIC SCREEN MEDIA REVIEW 2019 / VOLUME 7 / COMMENTARY ABSTRACT The need to re-structure established media systems needs to be acknowledged. In a situation where new services will be provided by different actors of the digital economy, the role of public service media (PSM) requires attention. If, generally, PSM are under pressure in Europe, the situation in small national markets is even more complicated. PSM are under pressure and also need to find ways to reformulate their role in society and culture. Broad discussions and new agreements between politi- cians, citizens and the media industry are necessary to change this situation. We will approach the question of whether a specific gap still exists in the media market that can be filled by PSM? The article will seek these answers based on various survey data and collected statistics in Estonia. INTRODUCTION Historically, public service media have home culture. On the other hand, in case of held a strong position in the European information overload and growing informa- countries. PSM have played a leading role tion disorder, PSM can help to safeguard as a reliable source of information, provider democratic developments. The role of PSM of quality entertainment, and educator. An in ensuring “that citizens have access to excellent summary of traditional public ser- well-researched and trustworthy journal- vice values is provided by Lowe and Maija- ism is central to the functioning of demo- nen (2019).