1 the Relationship Between the Zen Process of Awakening, As Taught

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Path to Bodhidharma

The Path to Bodhidharma The teachings of Shodo Harada Roshi 1 Table of Contents Preface................................................................................................ 3 Bodhidharma’s Outline of Practice ..................................................... 5 Zazen ................................................................................................ 52 Hakuin and His Song of Zazen ......................................................... 71 Sesshin ........................................................................................... 100 Enlightenment ................................................................................. 115 Work and Society ............................................................................ 125 Kobe, January 1995 ........................................................................ 139 Questions and Answers ................................................................... 148 Glossary .......................................................................................... 174 2 Preface Shodo Harada, the abbot of Sogenji, a three-hundred-year-old Rinzai Zen Temple in Okayama, Japan, is the Dharma heir of Yamada Mumon Roshi (1890-1988), one of the great Rinzai masters of the twentieth century. Harada Roshi offers his teachings to everyone, ordained monks and laypeople, men and women, young and old, from all parts of the world. His students have begun more than a dozen affiliated Zen groups, known as One Drop Zendos, in the United States, Europe, and Asia. The material -

Buddhism in America

Buddhism in America The Columbia Contemporary American Religion Series Columbia Contemporary American Religion Series The United States is the birthplace of religious pluralism, and the spiritual landscape of contemporary America is as varied and complex as that of any country in the world. The books in this new series, written by leading scholars for students and general readers alike, fall into two categories: some of these well-crafted, thought-provoking portraits of the country’s major religious groups describe and explain particular religious practices and rituals, beliefs, and major challenges facing a given community today. Others explore current themes and topics in American religion that cut across denominational lines. The texts are supplemented with care- fully selected photographs and artwork, annotated bibliographies, con- cise profiles of important individuals, and chronologies of major events. — Roman Catholicism in America Islam in America . B UDDHISM in America Richard Hughes Seager C C Publishers Since New York Chichester, West Sussex Copyright © Columbia University Press All rights reserved Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Seager, Richard Hughes. Buddhism in America / Richard Hughes Seager. p. cm. — (Columbia contemporary American religion series) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN ‒‒‒ — ISBN ‒‒‒ (pbk.) . Buddhism—United States. I. Title. II. Series. BQ.S .'—dc – Casebound editions of Columbia University Press books are printed on permanent and durable acid-free paper. -

Prefazione Teisho

Tetsugen Serra Zen Filosofia e pratica per una vita felice varia 3 08/05/19 10:45 SOMMARIO Prefazione . .9 Teisho . .9 Introduzione . .13 PARTE PRIMA CENNI STORICI DEL BUDDISMO ZEN . .17 Bodhidharma . .20 Hui Neng . .21 Dogen Kigen . .21 Keizan Jokin . .22 Il nostro lignaggio . .22 Harada Daiun Sogaku . .22 Ban Roshi . .23 Tetsujyo Deguchi . .24 LO ZEN: FILOSOFIA, RELIGIONE O STILE DI VITA? . .25 Filosofia zen . .25 Lo Zen come stile di vita . .28 PARTE SECONDA LA PRATICA ZEN . .33 Che cos’è la mente? . .34 Che cosa vuol dire risvegliarsi alla natura della propria vita? . .34 Che cos’è la consapevolezza? . .36 Che cos’è la meditazione? . .36 Che cos’è lo stato meditativo? . .37 4 4 08/05/19 10:46 COME SI MEDITA . .39 Perché si medita seduti . .39 Come accordare il corpo . .40 I Mudra nello Zen. Postura delle mani . .45 ZAZEN . .49 Come accordare il respiro . .49 Prima meditazione . .52 Occhi e nuca . .53 Bocca . .53 Collo, spalle e braccia . .54 Addome e gambe . .55 Kinhin, una meditazione speciale . .57 Le quattro meditazioni zazen . .60 Susokukan, contare i respiri da uno a dieci . .61 Zuisokukan, seguire i respiri . .66 Shikantaza, il puro essere . .67 Koan, le domande . .68 La pratica in un tempio zen . .70 Shin Getsu . .71 L’abito fa in monaco . .71 Nello Zendo . .72 Shakyamuni . .75 Dokusan, l’incontro diretto con il maestro . .78 PARTE TERZA MEDITARE A CASA . .83 Come creare il vostro Dojo . .83 L’immagine . .84 I fiori . .84 L’incenso . .85 La campana . .86 Il rituale . -

A Departure for Returning to Sabha: a Study of Koan Practice of Silence Jea Sophia Oh West Chester University of Pennsylvania, [email protected]

West Chester University Digital Commons @ West Chester University Philosophy College of Arts & Humanities 12-2017 A departure for returning to sabha: a study of koan practice of silence Jea Sophia Oh West Chester University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.wcupa.edu/phil_facpub Part of the Buddhist Studies Commons Recommended Citation Oh, J. S. (2017). A departure for returning to sabha: a study of koan practice of silence. International Journal of Dharma Studies, 5(12) http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/s40613-017-0059-7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Arts & Humanities at Digital Commons @ West Chester University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Philosophy by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ West Chester University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Oh International Journal of Dharma Studies (2017) 5:12 International Journal of DOI 10.1186/s40613-017-0059-7 Dharma Studies RESEARCH Open Access A departure for returning to sabha: a study of koan practice of silence Jea Sophia Oh Correspondence: [email protected] West Chester University of Abstract Pennsylvania, 700 S High St. AND 108D, West Chester, PA 19383, USA This paper deals with koan practice of silence through analyzing the Korean Zen Buddhist film, Why Has Boddhidharma Left for the East? (Bae, Yong-Kyun, Why Has Bodhidharma Left for the East? 1989). This paper follows Kibong's path along with the Buddha's journey of 1) departure, 2) journey in the middle way, and 3) returning with a particular focus on koan practice of silence as the transformative element of enlightenment. -

ZEN at WAR War and Peace Library SERIES EDITOR: MARK SELDEN

ZEN AT WAR War and Peace Library SERIES EDITOR: MARK SELDEN Drugs, Oil, and War: The United States in Afghanistan, Colombia, and Indochina BY PETER DALE SCOTT War and State Terrorism: The United States, Japan, and the Asia-Pacific in the Long Twentieth Century EDITED BY MARK SELDEN AND ALVIN Y. So Bitter Flowers, Sweet Flowers: East Timor, Indonesia, and the World Community EDITED BY RICHARD TANTER, MARK SELDEN, AND STEPHEN R. SHALOM Politics and the Past: On Repairing Historical Injustices EDITED BY JOHN TORPEY Biological Warfare and Disarmament: New Problems/New Perspectives EDITED BY SUSAN WRIGHT BRIAN DAIZEN VICTORIA ZEN AT WAR Second Edition ROWMAN & LITTLEFIELD PUBLISHERS, INC. Lanham • Boulder • New York • Toronto • Oxford ROWMAN & LITTLEFIELD PUBLISHERS, INC. Published in the United States of America by Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc. A wholly owned subsidiary of The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc. 4501 Forbes Boulevard, Suite 200, Lanham, Maryland 20706 www.rowmanlittlefield.com P.O. Box 317, Oxford OX2 9RU, UK Copyright © 2006 by Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc. Cover image: Zen monks at Eiheiji, one of the two head monasteries of the Sōtō Zen sect, undergoing mandatory military training shortly after the passage of the National Mobilization Law in March 1938. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information Available Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Victoria, Brian Daizen, 1939– Zen at war / Brian Daizen Victoria.—2nd ed. -

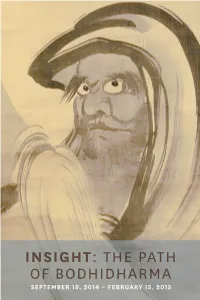

Insight: the Path of Bodhidharma

INSIGHT: THE PATH OF BODHIDHARMA SEPTEMBER 19, 2014 – FEBRUARY 15, 2015 Credited with introducing Chan (Zen in Japanese) Buddhism to China in the sixth century, the Indian monk Bodhidharma (known as Daruma in Japan) has become a well-known subject in Buddhist art. As Chan Buddhism gained popularity, various legends associated with the Chan patriarch evolved, and artists began to depict those legends alongside his conventional portraits. Traditional depictions of Bodhidharma were executed in ink monochrome with free, expressive brush strokes, alluding to his teaching on the spontaneous nature of reaching enlightenment through meditation. During the Edo period (1603-1868) in Japan, the depiction of this pious monk’s stern expression went through a radical change as he was often paired with a courtesan of the pleasure quarters—a parody to expose the hypocrisy of society. Today, Bodhidharma is still widely represented both in fine art and as a pop culture icon of good luck. Through an array of objects from paintings and sculptures to decorative objects and toys, Insight: The Path of Bodhidharma illustrates the visual and conceptual shift in depictions of this religious figure from the 17th century through today. BODHIDHARMA AS CHAN PATRIARCH One of the most common portrayals of Bodhidharma is a bust portrait revealing only the upper half of his body. In a three- quarter profile, he was frequently depicted in ways that emphasize his non-East Asian heritage and iconoclastic persona with large glaring eyes, a prominent nose and beard—sometimes an earring and red hooded robe. The primary goal of Bodhidharma’s teaching is to reach personal enlightenment through meditation that clears one’s mind from distracting thoughts and worldly concerns. -

Buddhist Bibio

Recommended Books Revised March 30, 2013 The books listed below represent a small selection of some of the key texts in each category. The name(s) provided below each title designate either the primary author, editor, or translator. Introductions Buddhism: A Very Short Introduction Damien Keown Taking the Path of Zen !!!!!!!! Robert Aitken Everyday Zen !!!!!!!!! Charlotte Joko Beck Start Where You Are !!!!!!!! Pema Chodron The Eight Gates of Zen !!!!!!!! John Daido Loori Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind !!!!!!! Shunryu Suzuki Buddhism Without Beliefs: A Contemporary Guide to Awakening ! Stephen Batchelor The Heart of the Buddha's Teaching: Transforming Suffering into Peace, Joy, and Liberation!!!!!!!!! Thich Nhat Hanh Buddhism For Beginners !!!!!!! Thubten Chodron The Buddha and His Teachings !!!!!! Sherab Chödzin Kohn and Samuel Bercholz The Spirit of the Buddha !!!!!!! Martine Batchelor 1 Meditation and Zen Practice Mindfulness in Plain English ! ! ! ! Bhante Henepola Gunaratana The Four Foundations of Mindfulness in Plain English !!! Bhante Henepola Gunaratana Change Your Mind: A Practical Guide to Buddhist Meditation ! Paramananda Making Space: Creating a Home Meditation Practice !!!! Thich Nhat Hanh The Heart of Buddhist Meditation !!!!!! Thera Nyanaponika Meditation for Beginners !!!!!!! Jack Kornfield Being Nobody, Going Nowhere: Meditations on the Buddhist Path !! Ayya Khema The Miracle of Mindfulness: An Introduction to the Practice of Meditation Thich Nhat Hanh Zen Meditation in Plain English !!!!!!! John Daishin Buksbazen and Peter -

Hakuin on Kensho: the Four Ways of Knowing/Edited with Commentary by Albert Low.—1St Ed

ABOUT THE BOOK Kensho is the Zen experience of waking up to one’s own true nature—of understanding oneself to be not different from the Buddha-nature that pervades all existence. The Japanese Zen Master Hakuin (1689–1769) considered the experience to be essential. In his autobiography he says: “Anyone who would call himself a member of the Zen family must first achieve kensho- realization of the Buddha’s way. If a person who has not achieved kensho says he is a follower of Zen, he is an outrageous fraud. A swindler pure and simple.” Hakuin’s short text on kensho, “Four Ways of Knowing of an Awakened Person,” is a little-known Zen classic. The “four ways” he describes include the way of knowing of the Great Perfect Mirror, the way of knowing equality, the way of knowing by differentiation, and the way of the perfection of action. Rather than simply being methods for “checking” for enlightenment in oneself, these ways ultimately exemplify Zen practice. Albert Low has provided careful, line-by-line commentary for the text that illuminates its profound wisdom and makes it an inspiration for deeper spiritual practice. ALBERT LOW holds degrees in philosophy and psychology, and was for many years a management consultant, lecturing widely on organizational dynamics. He studied Zen under Roshi Philip Kapleau, author of The Three Pillars of Zen, receiving transmission as a teacher in 1986. He is currently director and guiding teacher of the Montreal Zen Centre. He is the author of several books, including Zen and Creative Management and The Iron Cow of Zen. -

Contents Transcriptions Romanization Zen 1 Chinese Chán Sanskrit Name 1.1 Periodisation Sanskrit Dhyāna 1.2 Origins and Taoist Influences (C

7/11/2014 Zen - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Zen From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Zen is a school of Mahayana Buddhism[note 1] that Zen developed in China during the 6th century as Chán. From China, Zen spread south to Vietnam, northeast to Korea and Chinese name east to Japan.[2] Simplified Chinese 禅 Traditional Chinese 禪 The word Zen is derived from the Japanese pronunciation of the Middle Chinese word 禪 (dʑjen) (pinyin: Chán), which in Transcriptions turn is derived from the Sanskrit word dhyāna,[3] which can Mandarin be approximately translated as "absorption" or "meditative Hanyu Pinyin Chán state".[4] Cantonese Zen emphasizes insight into Buddha-nature and the personal Jyutping Sim4 expression of this insight in daily life, especially for the benefit Middle Chinese [5][6] of others. As such, it de-emphasizes mere knowledge of Middle Chinese dʑjen sutras and doctrine[7][8] and favors direct understanding Vietnamese name through zazen and interaction with an accomplished Vietnamese Thiền teacher.[9] Korean name The teachings of Zen include various sources of Mahāyāna Hangul 선 thought, especially Yogācāra, the Tathāgatagarbha Sutras and Huayan, with their emphasis on Buddha-nature, totality, Hanja 禪 and the Bodhisattva-ideal.[10][11] The Prajñāpāramitā Transcriptions literature[12] and, to a lesser extent, Madhyamaka have also Revised Romanization Seon been influential. Japanese name Kanji 禅 Contents Transcriptions Romanization Zen 1 Chinese Chán Sanskrit name 1.1 Periodisation Sanskrit dhyāna 1.2 Origins and Taoist influences (c. 200- 500) 1.3 Legendary or Proto-Chán - Six Patriarchs (c. 500-600) 1.4 Early Chán - Tang Dynasty (c. -

A Beginner's Guide to Meditation

ABOUT THE BOOK As countless meditators have learned firsthand, meditation practice can positively transform the way we see and experience our lives. This practical, accessible guide to the fundamentals of Buddhist meditation introduces you to the practice, explains how it is approached in the main schools of Buddhism, and offers advice and inspiration from Buddhism’s most renowned and effective meditation teachers, including Pema Chödrön, Thich Nhat Hanh, the Fourteenth Dalai Lama, Sharon Salzberg, Norman Fischer, Ajahn Chah, Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche, Shunryu Suzuki Roshi, Sylvia Boorstein, Noah Levine, Judy Lief, and many others. Topics include how to build excitement and energy to start a meditation routine and keep it going, setting up a meditation space, working with and through boredom, what to look for when seeking others to meditate with, how to know when it’s time to try doing a formal meditation retreat, how to bring the practice “off the cushion” with walking meditation and other practices, and much more. ROD MEADE SPERRY is an editor and writer for the Shambhala Sun magazine. Sign up to receive news and special offers from Shambhala Publications. Or visit us online to sign up at shambhala.com/eshambhala. A BEGINNER’S GUIDE TO Meditation Practical Advice and Inspiration from Contemporary Buddhist Teachers Edited by Rod Meade Sperry and the Editors of the Shambhala Sun SHAMBHALA Boston & London 2014 Shambhala Publications, Inc. Horticultural Hall 300 Massachusetts Avenue Boston, Massachusetts 02115 www.shambhala.com © 2014 by Shambhala Sun Cover art: André Slob Cover design: Liza Matthews All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. -

Omori Sogen the Art of a Zen Master

Omori Sogen The Art of a Zen Master Omori Roshi and the ogane (large temple bell) at Daihonzan Chozen-ji, Honolulu, 1982. Omori Sogen The Art of a Zen Master Hosokawa Dogen First published in 1999 by Kegan Paul International This edition first published in 2011 by Routledge 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon, OX14 4RN Simultaneously published in the USA and Canada by Routledge 711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017 Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business © The Institute of Zen Studies 1999 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 10: 0–7103–0588–5 (hbk) ISBN 13: 978–0–7103–0588–6 (hbk) Publisher’s Note The publisher has gone to great lengths to ensure the quality of this reprint but points out that some imperfections in the original copies may be apparent. The publisher has made every effort to contact original copyright holders and would welcome correspondence from those they have been unable to trace. Dedicated to my parents Contents Acknowledgements Introduction Part I - The Life of Omori Sogen Chapter 1 Shugyo: 1904–1934 Chapter 2 Renma: 1934–1945 Chapter 3 Gogo no Shugyo: 1945–1994 Part II - The Three Ways Chapter 4 Zen and Budo Chapter 5 Practical Zen Chapter 6 Teisho: The World of the Absolute Present Chapter 7 Zen and the Fine Arts Appendices Books by Omori Sogen Endnotes Index Acknowledgments Many people helped me to write this book, and I would like to thank them all. -

Yuibutsu Yobutsu 唯佛與佛 – Six Translations

Documento de estudo organizado por Fábio Rodrigues. Texto-base de Kazuaki Tanahashi em “Treasury of the True Dharma Eye – Zen Master Dogen's Shobo Genzo” (2013) / Study document organized by Fábio Rodrigues. Main text by Kazuaki Tanahashi in “Treasury of the True Dharma Eye - Zen Master Dogen's Shobo Genzo” (2013) 1. Kazuaki Tanahashi e Edward Brown (Treasury of the True Dharma Eye – Zen Master Dogen's Shobo Genzo, 2013) 2. Kazuaki Tanahashi e Edward Brown (Moon in a Dewdrop: Writings of Zen Master Dogen, 1985) 3. Gudo Wafu Nishijima and Chodo Cross (Shobogenzo: The True Dharma-eye Treasury, 1999/2007) 4. Rev. Hubert Nearman (The Treasure House of the Eye of the True Teaching, Shasta Abbey Press, 2007) 5. Kosen Nishiyama and John Stevens (1975) 6. 第三十八 唯佛與佛 (glasgowzengroup.com) 92 唯佛與佛 Yuibutsu yobutsu Eihei Dogen Only a buddha and a buddha Moon in a Dewdrop (1985): Only buddha and buddha 1 1. Undated. Not included in the primary or additional version of TTDE by Dogen. Together with "Birth and Death," this fascicle was included in an Eihei-ji manuscript called the "Secret Treasury of the True Dharma Eye." Kozen included it in the ninety-five-fascicle version. Other translation: Nishiyama and Stevens, vol. 3, pp. 129-35. Kosen Nishiyama and John Stevens (1975): Only a Buddha can transmit to a Buddha Shasta Abbey (2017): On ‘Each Buddha on His Own, Together with All Buddhas’ 1 Translator’s Introduction: The title of this text is a phrase that Dogen often employs. It is derived from a verse in the Lotus Scripture: “Each Buddha on His own,