Classification and Diagnosis of Aggressive Periodontitis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Importance of Chlorhexidine in Maintaining Periodontal Health

International Journal of Dentistry Research 2016; 1(1): 31-33 Review Article Importance of Chlorhexidine in Maintaining Periodontal IJDR 2016; 1(1): 31-33 December Health © 2016, All rights reserved www.dentistryscience.com Dr. Manpreet Kaur*1, Dr. Krishan Kumar1 1 Department of Periodontics, Post Graduate Institute of Dental Sciences, Rohtak-124001, Haryana, India Abstract Plaque is responsible for periodontal diseases. In order to prevent occurrence and progression of periodontal disease, removal of plaque becomes important. Mechanical tooth cleaning aids such as toothbrushes, dental floss, interdental brushes are used for removal of plaque. However, in some cases, chemical agents are used as an adjunct to mechanical methods to facilitate plaque control and prevent gingivitis. Chlorhexidine (CHX) mouthwash is the most commonly used and is considered as gold standard chemical agent. In this review, mechanism of action and other properties of CHX are discussed. Keywords: Plaque, Chemical agents, Chlorhexidine (CHX). INTRODUCTION Dental plaque is primary etiologic factor responsible for gingivitis and periodontitis [1]. Mechanical plaque control using toothbrushes, interdental brushes, dental floss prevent occurrence of gingivitis. However, in majority of population, mechanical methods of plaque control are ineffective due to less time spent[2] for plaque removal and lack of consistency. These limitations necessitate use of chemical plaque control agents as an adjunct to mechanical plaque control. Among various chemical agents, chlorhexidine (CHX) is considered to be a gold standard chemical agent for plaque control. Its structural formula consists of two symmetric 4-chlorophenyl rings and two biguanide groups connected by a central hexamethylene chain. Mechanism of action for CHX CHX is bactericidal and is effective against gram-positive bacteria, gram-negative bacteria and yeast organisms. -

Management of Rapidly Progressing Periodontitis: an Overview

Review Article Management of Rapidly Progressing Periodontitis: An Overview Sadat SMA1, Chowdhury NM2, Baten RBA3 Abstract causes rapid destruction of periodontal ligament and History of periodontal diseases recognition and alveolar bone which occurs in otherwise systemically treatment is ancient for at least 5000 years. There are healthy individuals generally of a younger age group but 1,8 different presentations of periodontal diseases. Rapidly patients may be older . A familial aggregation of the 9 progression periodontitis or aggressive periodontitis disease is also noted . It includes both localized and causes rapid destruction of the periodontium which leads generalized forms. It was previously known as early onset to early tooth loss. It may be generalized or localized. periodontitis that included three categories of periodontitis Periodontitis may be treated surgically or non-surgically - Pubertal, Juvenile and rapidly progressing but patients with rapidly progressing periodontitis do not periodontitis10,11. Early diagnosis and appropriate respond predictably to conventional therapy due to its treatment is necessary to prevent early tooth loss. multi factorial etiology. Successful management of the disease is difficult if not diagnosed early and treated Classification appropriately. Regenerative therapy, tissue engineering Classification of diseases helps the clinicians to develop a and genetic technologies are the new hope for the structure which can be used to identify diseases in relation treatment of rapidly progressing periodontitis. -

Probiotic Alternative to Chlorhexidine in Periodontal Therapy: Evaluation of Clinical and Microbiological Parameters

microorganisms Article Probiotic Alternative to Chlorhexidine in Periodontal Therapy: Evaluation of Clinical and Microbiological Parameters Andrea Butera , Simone Gallo * , Carolina Maiorani, Domenico Molino, Alessandro Chiesa, Camilla Preda, Francesca Esposito and Andrea Scribante * Section of Dentistry–Department of Clinical, Surgical, Diagnostic and Paediatric Sciences, University of Pavia, 27100 Pavia, Italy; [email protected] (A.B.); [email protected] (C.M.); [email protected] (D.M.); [email protected] (A.C.); [email protected] (C.P.); [email protected] (F.E.) * Correspondence: [email protected] (S.G.); [email protected] (A.S.) Abstract: Periodontitis consists of a progressive destruction of tooth-supporting tissues. Considering that probiotics are being proposed as a support to the gold standard treatment Scaling-and-Root- Planing (SRP), this study aims to assess two new formulations (toothpaste and chewing-gum). 60 patients were randomly assigned to three domiciliary hygiene treatments: Group 1 (SRP + chlorhexidine-based toothpaste) (control), Group 2 (SRP + probiotics-based toothpaste) and Group 3 (SRP + probiotics-based toothpaste + probiotics-based chewing-gum). At baseline (T0) and after 3 and 6 months (T1–T2), periodontal clinical parameters were recorded, along with microbiological ones by means of a commercial kit. As to the former, no significant differences were shown at T1 or T2, neither in controls for any index, nor in the experimental -

Periodontal Practice Patterns

PERIODONTAL PRACTICE PATTERNS A Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science in the Graduate School of the Ohio State University By Janel Kimberlay Yu, D.D.S. Graduate Program in Dentistry The Ohio State University 2010 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Angelo Mariotti, Advisor Dr. Jed Jacobson Dr. Eric Seiber Copyright by Janel Kimberlay Yu 2010 Abstract Background: Differences in the rates of dental services between geographic regions are important since major discrepancies in practice patterns may suggest an absence of evidence-based clinical information leading to numerous treatment plans for similar dental problems and the misallocation of limited resources. Variations in dental care to patients may result from characteristics of the periodontist. Insurance claims data in this study were compared to the characteristics of periodontal providers to determine if variations in practice patterns exist. Methods: Claims data, between 2000-2009 from Delta Dental of Ohio, Michigan, Indiana, New Mexico, and Tennessee, were examined to analyze the practice patterns of 351 periodontists. For each provider, the average number of select CDT periodontal codes (4000-4999), implants (6010), and extractions (7140) were calculated over two time periods in relation to provider variable, including state, urban versus rural area, gender, experience, location of training, and membership in organized dentistry. Descriptive statistics were performed to depict the data using measures of central tendency and measures of dispersion. ii Results: Differences in periodontal procedures were present across states. Although the most common surgical procedure in the study period was osseous surgery, greater increases over time were observed in regenerative procedures (bone grafts, biologics, GTR) when compared to osseous surgery. -

Aggressive Periodontitis and Its Multidisciplinary Focus: Review of the Literature

ODOVTOS-International Journal of Dental Sciences Frías et al: Aggressive Periodontitis and its Multidisciplinary Focus: Review of the Literature Aggressive Periodontitis and its Multidisciplinary Focus: Review of the Literature Periodontitis agresiva y su enfoque multidisciplinario: Revisión de literatura Maribel Frías-Muñoz DDS¹; Roxana Araujo-Espino DDS, MSc, PhD²; Víctor Manuel Martínez-Aguilar DDS, MSc³; Teresina Correa Alcalde DDS⁴; Luis Alejandro Aguilera-Galaviz DDS, MSc, PhD⁴; César Gaitán-Fonseca DDS, MSc, PhD⁴ 1. Estudiante, Maestría en Ciencias Biomédicas, Área Ciencias de la Salud, Universidad Autónoma de Zacatecas “Francisco García Salinas” (UAZ), Zacatecas, Zac., Mexico. 2. Docente-investigador, Unidad Académica de Enfermería, Área Ciencias de la Salud, Universidad Autónoma de Zacatecas “Francisco García Salinas” (UAZ), Zacatecas, Zac., Mexico. 3. Docente-investigador, Facultad de Odontología, Universidad Autónoma de Yucatán (UADY), Mérida, Yuc., Mexico. 4. Docente-investigador, Área Ciencias de la Salud, Maestría en Ciencias Biomédicas, Universidad Autónoma de Zacatecas “Francisco García Salinas” (UAZ), Zacatecas, Zac., Mexico. Correspondence to: Dr. César Gaitán-Fonseca - [email protected] Received: 1-V-2017 Accepted: 5-V-2017 Published Online First: 8-V-2017 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15517/ijds.v0i0.28869 ABSTRACT The purpose of this review is to have a current prospect of periodontal diseases and, in particular, aggressive periodontitis. To know its classification and clinical characteristics, such as the extent and age group affected, as well as its distribution in the population, etiology, genetic variations, among other factors that could affect the development of this disease. Also, reference is made to different diagnostic options and, likewise, the current treatment options. KEYWORDS Aggressive periodontitis; Periodontal diseases; Diagnosis. -

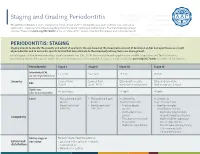

Staging and Grading Periodontitis

Staging and Grading Periodontitis The 2017 World Workshop on the Classification of Periodontal and Peri-Implant Diseases and Conditions resulted in a new classification of periodontitis characterized by a multidimensional staging and grading system. The charts below provide an overview. Please visit perio.org/2017wwdc for the complete suite of reviews, case definition papers, and consensus reports. PERIODONTITIS: STAGING Staging intends to classify the severity and extent of a patient’s disease based on the measurable amount of destroyed and/or damaged tissue as a result of periodontitis and to assess the specific factors that may attribute to the complexity of long-term case management. Initial stage should be determined using clinical attachment loss (CAL). If CAL is not available, radiographic bone loss (RBL) should be used. Tooth loss due to periodontitis may modify stage definition. One or more complexity factors may shift the stage to a higher level. Seeperio.org/2017wwdc for additional information. Periodontitis Stage I Stage II Stage III Stage IV Interdental CAL 1 – 2 mm 3 – 4 mm ≥5 mm ≥5 mm (at site of greatest loss) Severity Coronal third Coronal third Extending to middle Extending to middle RBL (<15%) (15% - 33%) third of root and beyond third of root and beyond Tooth loss No tooth loss ≤4 teeth ≥5 teeth (due to periodontitis) Local • Max. probing depth • Max. probing depth In addition to In addition to ≤4 mm ≤5 mm Stage II complexity: Stage III complexity: • Mostly horizontal • Mostly horizontal • Probing depths • Need for -

The Roots of Periodontology

THE ROOTS OF PERIODONTOLOGY NMDHA 24th Annual Scientific Session Dennis Miller DMD, MS Diplomate, American Board of Periodontology Oct 19, 2012 A word about the value of history…… Those who don’t know history are destined to repeat it. Edmond Burke (1729-1797) Those of you who don’t remember the past are condemned to repeat it. • George Santayama, 1890 The History of Dentistry • Barbers and blacksmiths were the first dentists in America • 1840 – opening of the first dental school, University of Baltimore • 1859 – ADA was founded, oldest and largest national Dental Society in the world • 1890 – Dr. John Riggs describes periodontal disease • Calls it Riggs disease or pyorrhea • Marketed Anti-Riggs mouthwash (156 proof) • 1896 – Dr. G.V. Black who is known as the father of modern dentistry, describes cavity preparations • 1906 – Dr. C. Edmund Kells exposes first dental radiograph; also the first to use female dental assistants and surgical aspirators • 1929 – Orthodontics recognized as first dental specialty History of Periodontics • 1914 – Dr. Grace Rodgers Spalding and Dr. Gillette Hayden (both physicians) formed the American Academy of Oral Prophylaxis and Periodontology • 1919 – became the American Academy of Periodontology • Circa 1941 - Periodontics recognized as a dental specialty History of Hygiene • 1867 – Lucy Hobbs Taylor graduated from Ohio College of Dental Surgery as a hygienist • 1884 – paper presented at the NY 1st District Dental Society meeting advocating teeth cleaning for prevention, done by “staff” • 1923 – formation of ADHA Historical names of periodontitis • Loculosis • Blennorrhea gingivae • Periostitis • Alveolodental periostitis • Infectious arthrodental gingivitis • Phagedenic pericementitis • Expulsive gingivitis • Symptomatic alveolar arthritis • Smutz pyorrhea • Riggs disease • Periodontoclasia • Pyorrhea alveolaris The roots of Periodontology • The roots of the dental profession including periodontics and dental hygiene were not concocted by some entrepreneur. -

Tobacco and Your Oral Health

Oral Wellness Series Tobacco and Your Oral Health We all know smoking is bad for us, but did you know that chewing tobacco is just as harmful to your oral health as cigarettes? Tobacco causes bad breath, which nobody likes, but it has far more serious risks to your oral health, including: • Mouth sores • Slow healing after oral surgery • Difficulties correcting cosmetic dental problems • Stained teeth and tongue • Dulled sense of taste and smell The Biggest Risk? Did you know tobacco Cancer. The Centers for Disease Control have linked smoking and use is a huge risk factor tobacco use to oral cancer. Oral cancer is the eighth most common cancer in the U.S., and it’s very difficult to detect. As a result, two- for gum disease? thirds of all cases are diagnosed in late stages, making treatment and survival difficult.1 Tobacco and Gum Disease Tobacco use is also a huge risk factor for gum disease, a leading cause of tooth loss. More than 41% of daily smokers over the age of 65 are toothless because of gum disease, compared to only 20% of non-smokers.2 Maintain good oral health by avoiding tobacco. It keeps your whole body healthier. The Effects of Smoking on Your Gums Smoking reduces blood flow to your gums, cutting Is Smokeless Tobacco Safer? off vital nutrients and preventing bones from healing. Smokeless tobacco—chew, dip and snuff—is not This lets bacteria from tartar infect surrounding tissue, regulated by the FDA so it’s hard to know what’s in it. 3 forming deep pockets between teeth and gums. -

Treatment of Localized Aggressive Periodontitis Regenerative Periodontal Therapy Offers Alternative to Extraction/Implant Placement Ahmad Soolari, DMD, MS

Inside PERIODONTICS PEER-REVIEWED Treatment of Localized Aggressive Periodontitis Regenerative periodontal therapy offers alternative to extraction/implant placement Ahmad Soolari, DMD, MS ue to the effect of im- with inconsistent margins, which could be was localized aggressive periodontitis. The plant-related compli- measured from the cementoenamel junc- patient’s medical history was unremarkable, cations, the longevity of tion or from the crest of the alveolar bone but a significant finding was the retention of implants is often ques- to the base of the defect. A periapical ra- primary teeth with premolar impaction on tionable, even when diograph showed angular bone loss on the the lower right side. The patient was later compared with that of distal aspect of tooth No. 24 with an angle referred to an orthodontist for consultation. compromised but suc- of almost 45°. The interproximal space be- The goal of regenerative periodontal cessfully treated natural teeth. This article de- tween tooth No. 24 and tooth No. 23 was the therapy is to improve a tooth’s prognosis by Dscribes a case of severe, localized periodontal only site with severe bone loss throughout regenerating the supporting structures. In disease in which the patient rejected a recom- the patient’s mouth; therefore, the diagnosis this case, the prognosis for tooth No. 24 was mendation to undergo extraction followed by implant placement and restoration in favor of receiving regenerative periodontal therapy to save the natural tooth. Case Report A 17-year-old female patient presented with bone loss associated with tooth No. 24. A clinical examination and periodontal eval- uation (ie, assessment of mobility, probing depth, bleeding on probing, plaque score, and clinical attachment loss) revealed severe horizontal and vertical bone loss, deep prob- ing depth with bleeding, class II mobility, a FIG. -

American Academy of Periodontology Task Force Report on the Update to the 1999 Classification of Periodontal Diseases and Conditions*

J Periodontol • July 2015 American Academy of Periodontology Task Force Report on the Update to the 1999 Classification of Periodontal Diseases and Conditions* The American Academy of Periodontology (AAP) peri- 4 mm CAL, and Severe =‡5 mm CAL.’’ Numerous odically publishes reports, statements, and guidelines important studies since 1999 have used similar pa- on a variety of topics relevant to periodontics. These rameters to define periodontitis. For example, the papers are developed by an appointed committee of recent epidemiologic studies outlining the prevalence experts, and the documents are reviewed and ap- of periodontitis in the United States used attachment proved by the AAP Board of Trustees. loss parameters to define various severities of peri- odontitis.2,3 It is recognized that CAL is of importance for the scientific advancement of the knowledge of n 2014, the American Academy of Periodontology periodontitis. However, in clinical practice, measure- Board of Trustees charged a Task Force to develop ment of CAL has proven to be challenging, and is time Ia clinical interpretation of the 1999 Classification consuming. Measuring the location of the cemento- of Periodontal Diseases and Conditions to address enamel junction (CEJ) when the gingival margin is concerns expressed by the education community, the located coronal to the CEJ is difficult and may involve American Board of Periodontology, and the practic- some guesswork when the CEJ is not readily evident ing community that the current Classification pres- via tactile sensation. These issues can result in ex- ents challenges for the education of dental students aminations being performed in which, rather than and implementation in clinical practice. -

Idiopathic Gingival Fibromatosis Associated with Generalized Aggressive Periodontitis: a Case Report

Clinical P RACTIC E Idiopathic Gingival Fibromatosis Associated with Generalized Aggressive Periodontitis: A Case Report Contact Author Rashi Chaturvedi, MDS, DNB Dr. Chaturvedi Email: rashichaturvedi@ yahoo.co.in ABSTRACT Idiopathic gingival fibromatosis, a benign, slow-growing proliferation of the gingival tissues, is genetically heterogeneous. This condition is usually part of a syndrome or, rarely, an isolated disorder. Aggressive periodontitis, another genetically transmitted disorder of the periodontium, typically results in severe, rapid destruction of the tooth- supporting apparatus. The increased susceptibility of the host population with aggressive periodontitis may be caused by the combined effects of multiple genes and their inter- action with various environmental factors. Functional abnormalities of neutrophils have also been implicated in the etiopathogenesis of aggressive periodontitis. We present a rare case of a nonsyndromic idiopathic gingival fibromatosis associated with general- ized aggressive periodontitis. We established the patient’s diagnosis through clinical and radiologic assessment, histopathologic findings and immunologic analysis of neutrophil function with a nitro-blue-tetrazolium reduction test. We describe an interdisciplinary approach to the treatment of the patient. For citation purposes, the electronic version is the definitive version of this article: www.cda-adc.ca/jcda/vol-75/issue-4/291.html diopathic gingival fibromatosis is a rare syndromic, have been genetically linked to hereditary condition -

Dentine Hypersensitivity: Analysis of Self-Care Products§

Periodontics Periodontics Dentine hypersensitivity: analysis of self-care products§ Cassiano Kuchenbecker Rösing(a) Abstract: Dentine hypersensitivity is a condition that is often present in (b) Tiago Fiorini individuals, leading them to seek dental treatment. It has been described Diego Nique Liberman(b) Juliano Cavagni(b) as an acute, provoked pain that is not attributable to other dental prob- lems. Its actual prevalence is unknown, but it is interpreted as very un- pleasant by individuals. Several therapeutic alternatives are available to (a) Professor of Periodontology; (b)Graduate Student, Graduate Program in Dentistry manage dentine hypersensitivity, involving both in-office treatment and – School of Dentistry, Federal University of home-use products. The aim of this literature review was to evaluate self- Rio Grande do Sul, Porto Alegre, RS, Brazil. care products for managing dentine hypersensitivity. Among the prod- ucts available, dentifrices and fluorides are the most studied self-care products, with positive effects. However, a high percentage of individu- als is affected by the placebo effect. Among dentifrices, those containing potassium salts seem to be the most promising. Dental professionals need to understand the advantages and limitations of these therapies and use this knowledge in a positive approach that might help in decreasing den- tine hypersensitivity among patients. Descriptors: Dentin hypersensitivity; Review; Dental devices, home-care. § Paper presented at the “Oral Health Self-Care Products: Realities and