Final Draft Dissertation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Reexamination of "Eternity" in Ecclesiastes 3:11

BiBLiOTHECA SACRA 165 (January-March 2008): 39-57 A REEXAMINATION OF "ETERNITY" IN ECCLESIASTES 3:11 Brian P. Gault HE PHRASE "GOD HAS PLACED ETERNITY IN THE HUMAN HEART" (Eccles. 3I11)1 has become cliché in contemporary missiology Tand a repeated refrain from many Christian pulpits today. In his popular work, Eternity in Their Hearts, missiologist Don Richardson reports on stories that reveal a belief in the one true God in many cultures around the world. Based on Qoheleth's words Richardson proposes that God has prepared the world for the gos pel of Jesus Christ.2 In support of his thesis Richardson appeals to the words of the late scholar Gleason Archer, "Humankind has a God-given ability to grasp the concept of eternity."3 While com monly accepted by scholars and laypersons alike, this notion is cu riously absent from the writings of the early church fathers4 as well as the major theological treatise of William Carey, the founder of the modern missionary movement.5 In fact modern scholars have suggested almost a dozen different interpretations for this verse. In Brian P. Gault is a Ph.D. student in Hebrew Bible and the Ancient Near East at Hebrew Union College—Jewish Institute of Religion, Cincinnati, Ohio. 1 Unless noted otherwise, all Scripture quotations are those of the present writer. 2 Don Richardson, Eternity in Their Hearts (Ventura, CA: Regal, 1981), 28. 3 Personal interview cited by Don Richardson, "Redemptive Analogy," in Perspec tives on the World Christian Movement, ed. Ralph D. Winter and Steven C. Hawthorne (Pasadena, CA: William Carey Library, 2000), 400. -

The Humanity of the Talmud: Reading for Ethics in Bavli ʿavoda Zara By

The Humanity of the Talmud: Reading for Ethics in Bavli ʿAvoda Zara By Mira Beth Wasserman A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Joint Doctor of Philosophy with Graduate Theological Union, Berkeley in Jewish Studies in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Daniel Boyarin, chair Professor Chana Kronfeld Professor Naomi Seidman Professor Kenneth Bamberger Spring 2014 Abstract The Humanity of the Talmud: Reading for Ethics in Bavli ʿAvoda Zara by Mira Beth Wasserman Joint Doctor of Philosophy with Graduate Theological Union, Berkeley University of California, Berkeley Professor Daniel Boyarin, chair In this dissertation, I argue that there is an ethical dimension to the Babylonian Talmud, and that literary analysis is the approach best suited to uncover it. Paying special attention to the discursive forms of the Talmud, I show how juxtapositions of narrative and legal dialectics cooperate in generating the Talmud's distinctive ethics, which I characterize as an attentiveness to the “exceptional particulars” of life. To demonstrate the features and rewards of a literary approach, I offer a sustained reading of a single tractate from the Babylonian Talmud, ʿAvoda Zara (AZ). AZ and other talmudic discussions about non-Jews offer a rich resource for considerations of ethics because they are centrally concerned with constituting social relationships and with examining aspects of human experience that exceed the domain of Jewish law. AZ investigates what distinguishes Jews from non-Jews, what Jews and non- Jews share in common, and what it means to be a human being. I read AZ as a cohesive literary work unified by the overarching project of examining the place of humanity in the cosmos. -

Dogma, Heresy, and Classical Debates: Creating Jewish Unity in an Age of Confusion

Dogma, Heresy, and Classical Debates: Creating Jewish Unity in an Age of Confusion Byline: Rabbi Hayyim Angel Judaism includes the basic tenets of belief in one God, divine revelation of the Torah including an Oral Law, divine providence, reward-punishment, and a messianic redemption. Although there have been debates over the precise definitions and boundaries of Jewish belief, these core beliefs have been universally accepted as part of our tradition.[1] The question for believing Jews today is, how should we relate to the overwhelming majority of contemporary Jews, who likely do not fully believe in classical Jewish beliefs? Two medieval models shed light on this question. Rambam: Dogmatic Approach Rambam insists that proper belief is essential. Whether one intentionally rejects Jewish beliefs, or is simply mistaken or uninformed, non-belief leads to one’s exclusion from the Jewish community and from the World to Come: When a person affirms all these Principles, and clarifies his faith in them, he becomes part of the Jewish People. It is a mitzvah to love him, have mercy on him, and show him all the love and brotherhood that God has instructed us to show our fellow Jews. Even if he has transgressed out of desire and the overpowering influence of his base nature, he will be punished accordingly but he will have a share in the World to Come. But one who denies any of these Principles has excluded himself from the Jewish People and denied the essence [of Judaism]. He is called a heretic, an epikoros, and “one who has cut off the seedlings.” It is a mitzvah to hate and destroy such a person, as it says (Psalms 139:21), “Those who hate You, God, I shall hate.” (Rambam, Introduction to Perek Helek) Scholars of Rambam generally explain that Rambam did not think of afterlife as a reward. -

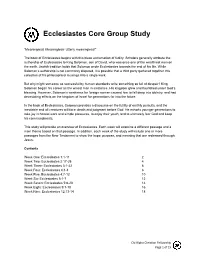

Ecclesiastes Core Group Study

Ecclesiastes Core Group Study “Meaningless! Meaningless! Utterly meaningless!” The book of Ecclesiastes begins with this bleak exclamation of futility. Scholars generally attribute the authorship of Ecclesiastes to King Solomon, son of David, who was once one of the wealthiest men on the earth. Jewish tradition holds that Solomon wrote Ecclesiastes towards the end of his life. While Solomon’s authorship is not commonly disputed, it is possible that a third party gathered together this collection of his philosophical musings into a single work. But why might someone so successful by human standards write something so full of despair? King Solomon began his career as the wisest man in existence. His kingdom grew and flourished under God’s blessing. However, Solomon’s weakness for foreign women caused him to fall deep into idolatry, and had devastating effects on the kingdom of Israel for generations far into the future. In the book of Ecclesiastes, Solomon provides a discourse on the futility of earthly pursuits, and the inevitable end all creatures will face: death and judgment before God. He exhorts younger generations to take joy in honest work and simple pleasures, to enjoy their youth, and to ultimately fear God and keep his commandments. This study will provide an overview of Ecclesiastes. Each week will examine a different passage and a main theme based on that passage. In addition, each week of the study will include one or more passages from the New Testament to show the hope, purpose, and meaning that are redeemed through Jesus. Contents Week One: Ecclesiastes 1:1-11 2 Week Two: Ecclesiastes 2:17-26 4 Week Three: Ecclesiastes 3:1-22 6 Week Four: Ecclesiastes 4:1-3 8 Week Five: Ecclesiastes 4:7-12 10 Week Six: Ecclesiastes 5:1-7 12 Week Seven: Ecclesiastes 5:8-20 14 Week Eight: Ecclesiastes 9:1-10 16 Week Nine: Ecclesiastes 12:13-14 18 Chi Alpha Christian Fellowship Page 1 of 19 Week One: Ecclesiastes 1:1-11 Worship Idea: Open in prayer, then sing some worship songs Opening Questions: 1. -

The Relationship Between Targum Song of Songs and Midrash Rabbah Song of Songs

THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN TARGUM SONG OF SONGS AND MIDRASH RABBAH SONG OF SONGS Volume I of II A thesis submitted to The University of Manchester for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Humanities 2010 PENELOPE ROBIN JUNKERMANN SCHOOL OF ARTS, HISTORIES, AND CULTURES TABLE OF CONTENTS VOLUME ONE TITLE PAGE ............................................................................................................ 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS ............................................................................................. 2 ABSTRACT .............................................................................................................. 6 DECLARATION ........................................................................................................ 7 COPYRIGHT STATEMENT ....................................................................................... 8 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS AND DEDICATION ............................................................... 9 CHAPTER ONE : INTRODUCTION ........................................................................... 11 1.1 The Research Question: Targum Song and Song Rabbah ......................... 11 1.2 The Traditional View of the Relationship of Targum and Midrash ........... 11 1.2.1 Targum Depends on Midrash .............................................................. 11 1.2.2 Reasons for Postulating Dependency .................................................. 14 1.2.2.1 Ambivalence of Rabbinic Sources Towards Bible Translation .... 14 1.2.2.2 The Traditional -

Ecclesiastes – “It’S ______About _____”

“DISCOVERING THE UNREAD BESTSELLER” Week 18: Sunday, March 25, 2012 ECCLESIASTES – “IT’S ______ ABOUT _____” BACKGROUND & TITLE The Hebrew title, “___________” is a rare word found only in the Book of Ecclesiastes. It comes from a word meaning - “____________”; in fact, it’s talking about a “_________” or “_________”. The Septuagint used the Greek word “__________” as its title for the Book. Derived from the word “ekklesia” (meaning “assembly, congregation or church”) the title again (in the Greek) can simply be taken to mean - “_________/_________”. AUTHORSHIP It is commonly believed and accepted that _________authored this Book. Within the Book, the author refers to himself as “the son of ______” (Ecclesiastes 1:1) and then later on (in Ecclesiastes 1:12) as “____ over _____ in Jerusalem”. Solomon’s extensive wisdom; his accomplishments, and his immense wealth (all of which were God-given) give further credence to his work. Outside the Book, _______ tradition also points to Solomon as author, but it also suggests that the text may have undergone some later editing by _______ or possibly ____. SNAPSHOT OF THE BOOK The Book of Ecclesiastes describes Solomon’s ______ for meaning, purpose and satisfaction in life. The Book divides into three different sections - (1) the _____ that _______ is ___________ - (Ecclesiastes 1:1-11); (2) the ______ that everything is meaningless (Ecclesiastes 1:12-6:12); and, (3) the ______ or direction on how we should be living in a world filled with ______ pursuits and meaninglessness (Ecclesiastes 7:1-12:14). That last section is important because the Preacher/Teacher ultimately sees the emptiness and futility of all the stuff people typically strive for _____ from God – p______ – p_______ – p________ - and p________. -

The Anti-Samaritan Attitude As Reflected in Rabbinic Midrashim

religions Article The Anti‑Samaritan Attitude as Reflected in Rabbinic Midrashim Andreas Lehnardt Faculty of Protestant Theology, Johannes Gutenberg‑University Mainz, 55122 Mainz, Germany; lehnardt@uni‑mainz.de Abstract: Samaritans, as a group within the ranges of ancient ‘Judaisms’, are often mentioned in Talmud and Midrash. As comparable social–religious entities, they are regarded ambivalently by the rabbis. First, they were viewed as Jews, but from the end of the Tannaitic times, and especially after the Bar Kokhba revolt, they were perceived as non‑Jews, not reliable about different fields of Halakhic concern. Rabbinic writings reflect on this change in attitude and describe a long ongoing conflict and a growing anti‑Samaritan attitude. This article analyzes several dialogues betweenrab‑ bis and Samaritans transmitted in the Midrash on the book of Genesis, Bereshit Rabbah. In four larger sections, the famous Rabbi Me’ir is depicted as the counterpart of certain Samaritans. The analyses of these discussions try to show how rabbinic texts avoid any direct exegetical dispute over particular verses of the Torah, but point to other hermeneutical levels of discourse and the rejection of Samari‑ tan claims. These texts thus reflect a remarkable understanding of some Samaritan convictions, and they demonstrate how rabbis denounced Samaritanism and refuted their counterparts. The Rabbi Me’ir dialogues thus are an impressive literary witness to the final stages of the parting of ways of these diverging religious streams. Keywords: Samaritans; ancient Judaism; rabbinic literature; Talmud; Midrash Citation: Lehnardt, Andreas. 2021. The Anti‑Samaritan Attitude as 1 Reflected in Rabbinic Midrashim. The attitudes towards the Samaritans (or Kutim ) documented in rabbinical literature 2 Religions 12: 584. -

ALTERNATIVE KEVURA METHODS Jeremy Kalmanofsky

Kalmanofsky, Spring 2017 Alternative Kevura Methods ALTERNATIVE KEVURA METHODS Jeremy Kalmanofsky This teshuvah was adopted by the CJLS on June 7, 2017, by a vote of 10 in favor, 7 opposed, and 3 abstaining. Members voting in favor: Rabbis Aaron Alexander, Pamela Barmash, Noah Bickart, Elliot Dorff, Joshua Heller, Jeremy Kalmanofsky, Amy Levin, Daniel Nevins, Micah Peltz, Avram Reisner and David Schuck. Members opposed: Rabbis Baruch Frydman-Kohl, Reuven Hammer, David Hoffman, Gail Labovitz, Jonathan Lubliner, and Paul Plotkin. Members abstaining: Rabbis Susan Grossman, Jan Kaufman, and Iscah Waldman, Question: Contemporary Jews sometimes seek alternative mortuary methods in order to be more ecologically sustainable and economical. Can Jews utilize alternative methods or is burial required? What does Halakhic tradition demand for how Jews treat dead bodies? Answer: The Torah’s very first chapters assert that human remains should decompose in the earth. Describing human mortality, God tells Adam [Genesis 3.19]: “You are dust and to dust you will return.” -Jewish treatment for human remains has always been in [לכתחילה] In this spirit, the optimal ground burial. The Torah legislates this norm at Deuteronomy 21:22-23:1 לֹא-תָלִין נִבְ לָתֹו עַל-הָעֵץ, כִ י-קָ בֹור תִ קְבְרֶ ּנּו בַּיֹום הַהּוא The Committee on Jewish Law and Standards of the Rabbinical Assembly provides guidance in matters of halkhhah for the Conservative movement. The individual rabbi, however, is the authority for the interpretation and application of all matters of halakhah. 1 This commandment comes in the context of the rules for executing criminals. It might seem off-putting to base the treatment of all bodies upon this unfortunate paradigm. -

The History of the Jews

TH E H I STO RY O F TH E JEWS B Y fid t t at h menta l J B E 39 . b ) , iBb PROFES S OR WI H I T RY AND LI T RAT RE OF J E S H S O E U , B RE I LL G I I ATI W C C C o. HE UN ON O E E, N NN , S ECOND EDI TI ON Revised a nd E n la rged NEW YORK BLOCH PUBLI SHING COMPANY “ ” TH E J EWI SH B OOK CONCERN PYRI G T 1 1 0 1 2 1 CO H , 9 , 9 , B LOCH PUBLISHI NG COM PANY P re ss o f % i J . J L t t l e I m . 86 ve s Co p a n y w rk Y U . S . Ne . o , A TAB LE OF CONTENTS CH APTE R PAGE R M TH E AB YL I A APTI VI TY 86 B C To I . F O B ON N C , 5 , TH E TR CTI TH E EC D M PL DES U ON OF S ON TE E, 0 7 C E . R M TH E TR CTI R AL M 0 TO II . F O DES U ON OF JE US E , 7 , TH E MPL TI TH E I A CO E ON OF M SH N H , II - I . ERA TH E ALM D 200 600 OF T U , Religiou s Histo ry o f t h e Era IV. R M TH E I LA M 622 TO TH E ERA F O R SE OF IS , , OF TH E R AD 1 0 6 C US ES , 9 Literary Activity o f t h e P erio d - V. -

The Two Roles of Government in Israel

The Two Roles of Government in Israel Timely Torah, June 13th, 2021 1. Talmud Bavli, Brachos 10a-b הרָארמ ב :אְמנוּנַַַמ ָידּא ״בִמתַכ ִיכּיְ םמֶכְחִה יָוָּ ֵַﬠוִֹיד ֵשׁ פּ רֶ בָ דּ ״רָ — הנפּרשׁבּשׁ בּישׁןצ ת םיקֵדדּ ,ְﬠ וֹייּןוֵָֹ אְלשׂ ֶיֵַָﬠי @ֲִַהִוֵַּ שׁרוּבּ ִמיקָּהכּ ְַָדוֹ ִמיקָּהכּ שׁרוּבּ @ֲִַהִוֵַּ ֶיֵַָﬠי אְלשׂ וֹייּןוֵָֹ ,ְﬠ םיקֵדדּ ת בּישׁןצ הנפּרשׁבּשׁ ִוּהﬠיּלְשׁקִחז ְ.וּהקִַיִחזָי ִ:רוּהתמיּלְָא שׁיֲֵָי וּהגְַּיֵﬠַי ,ָהיאדּבְּ חיְָכַּאשׁכַ ְןַאבִּ ִוּהאֵיּדְַּלְ לֲַלזָ ְַג ַ יאֵבּ ְ,בַשׁאח ֶָ ר:מ״או אא.ֶנּ״חא ללַביּא @תֱל הוֵָֹוְֶּריּהֵַלַ ִֶא ְֵָ ָ ָ ֶ וֶָֹרהֵַ תללַיּ אֶ״ארמא ֱִאילָשׁע ֵַלגיבּ ֲַדּזאלְ ְַאָחאבַ ֶןבּ יבּהָוֹרם ְַאְַשׁכּןִח ִָדּהיכ ַגּבּאְי ְִָזחיּקהוַּ ֵיֵליִת ֲַאמר: ְָשׁיﬠהוּ ְיַ . With regard to redemption and prayer, the Gemara tells the story of Hezekiah’s illness, his prayer to God, and subsequent recuperation. Rav Hamnuna said: What is the meaning of that which is written praising the Holy One, Blessed be He: “Who is like the wise man, and who knows the interpretation [pesher] of the matter” (Ecclesiastes 8:1)? This verse means: Who is like the Holy One, Blessed be He, Who knows how to effect compromise [peshara] between two righteous individuals, between Hezekiah, the king of Judea, and Isaiah the prophet. They disagreed over which of them should visit the other. Hezekiah said: Let Isaiah come to me, as that is what we find with regard to Elijah the prophet, who went to Ahab, the king of Israel, as it is stated: “And Elijah went to appear to Ahab” (I Kings 18:2). This proves that it is the prophet who must seek out the king. -

Jewish Thought Journal of the Goldstein-Goren International Center for Jewish Thought

Jewish Thought Journal of the Goldstein-Goren International Center for Jewish Thought Editors Michal Bar-Asher Siegal Jonatan Meir Shalom Sadik Haim Kreisel (editor-in-chief) Editorial Secretary Asher Binyamin Volume 1 Faith and Heresy Beer-Sheva, 2019 Jewish Thought is published once a year by the Goldstein-Goren International Center for Jewish Thought. Each issue is devoted to a different topic. Topics of the following issues are as follows: 2020: Esotericism in Jewish Thought 2021: New Trends in the Research of Jewish Thought 2022: Asceticism in Judaism and the Abrahamic Religions Articles for the next issue should be submitted by September 30, 2019. Manuscripts for consideration should be sent, in Hebrew or English, as MS Word files, to: [email protected] The articles should be accompanied by an English abstract. The views and opinions expressed in the articles are those of the authors alone. The journal is open access: http://in.bgu.ac.il/en/humsos/goldstein-goren/Pages/Journal.aspx The Hebrew articles were edited by Dr. David Zori and Shifra Zori. The articles in English were edited by Dr. Julie Chajes. Address: The Goldstein-Goren International Center for Jewish Thought, Ben-Gurion University of the Negev, PO Box 653, Beer-Sheva 8410501. © All Rights Reserved This issue is dedicated to Prof. Daniel J. Lasker for his 70Th birthday Table of Contents English Section Foreward 7 Michal Bar-Asher The Minim of the Babylonian Talmud 9 Siegal Menahem Kellner The Convert as the Most Jewish of Jews? 33 On the Centrality of Belief (the Opposite of Heresy) in Maimonidean Judaism Howard Kreisel Back to Maimonides’ Sources: 53 The Thirteen Principles Revisited George Y. -

Did the Rabbis Reject the Roman Public Latrine?

1980-09_Babesch_13_Wilfand 24-08-2009 11:38 Pagina 183 BABESCH 84 (2009), 183-196. doi: 10.2143/BAB.84.0.2041644. Did the Rabbis Reject the Roman Public Latrine? Yael Wilfand Abstract This study examines archaeological evidence and rabbinic texts in order to challenge recent scholarly claims that the rabbis in Palestine rejected the Roman public latrine because of the lack of privacy during ‘bodily exertion’. By reevaluating both the written and material evidence within the appropriate geographical context (differenti- ating between Babylonian and Palestinian), I argue that there is no evidence that suggests rabbis living in Palestine rejected Roman public latrines. However, the evidence does suggest that in Babylonia, where Roman public latrines were not used, such a rejection did exist. In order to explain the different attitudes towards public latrines, I sug- gest that the Zoroastrian cultural environment may have influenced the Babylonian rabbis to develop their rejection.* INTRODUCTION modesty in the toilet in order to deter the Jewish population from using these facilities.4 They imply In his article ‘Slums, Sanitation, and Mortality in that for this reason, Roman public latrines were the Roman World’, Alex Scobie pointed out the found mainly in cities with a majority of gentiles, relation between privacy concerns and the design while in areas with a majority of Jews different of latrines: latrines were used.5 Privacy is ... felt to be a normal necessity in If such a rejection of the Roman latrine pre- modern Western societies, both for defecation vailed among the rabbis in Palestine, it may affect and sexual intercourse….