In Search of Kohelet

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wind Chasers Beware- Ecclesiastes 1

Wind Chasers Beware Eccleiase 1 Wisdom Literature While other civilizations shared in wisdom literature, the major difference is the Hebrew wisdom writings acknowledged one God, denying materialism and [the worship of many gods.] 2 Types of Wisdom Literature: Didactic (Practical/ Teaching) and Philosophical/Pessimistic (Critical/ Reflective/Questioning). The goal of wisdom is a proper relationship with YAHWEH. Wisdom Focus Didactic wisdom literature advocates the development of prudential habits, skills, and virtues. The aim is to develop moral character, personal success and happiness, safety, and well-being. Proverbs is an example of this type. Philosophical/Pessimistic wisdom literature delves deeper into issues facing mankind. It portrays the emptiness and folly of the search for insight and understanding apart from God. Job and Ecclesiastes are examples of this type. The words of the Preacher, the son of David, king in Jerusalem. Ecclesiastes 1:1 Consider the Source Advice is only as good as the one giving it. Only 2 ways of learning something: Personal experience or 2nd hand. Solomon was the wisest man that ever lived. (See 1 Kings 3:11-14) Solomon saw one of Israel's wealthier periods. Ecclesiastes 1:2-6 “ Vanity of vanities,” says the Preacher, “Vanity of vanities! All is vanity.” What advantage does man have in all his work which he does under the sun? A generation goes and a generation comes, but the earth remains forever. Also, the sun rises and the sun sets; and hastening to its place it rises there again. Blowing toward the south, then turning toward the north, the wind continues swirling along; and on its circular courses the wind returns. -

A Reexamination of "Eternity" in Ecclesiastes 3:11

BiBLiOTHECA SACRA 165 (January-March 2008): 39-57 A REEXAMINATION OF "ETERNITY" IN ECCLESIASTES 3:11 Brian P. Gault HE PHRASE "GOD HAS PLACED ETERNITY IN THE HUMAN HEART" (Eccles. 3I11)1 has become cliché in contemporary missiology Tand a repeated refrain from many Christian pulpits today. In his popular work, Eternity in Their Hearts, missiologist Don Richardson reports on stories that reveal a belief in the one true God in many cultures around the world. Based on Qoheleth's words Richardson proposes that God has prepared the world for the gos pel of Jesus Christ.2 In support of his thesis Richardson appeals to the words of the late scholar Gleason Archer, "Humankind has a God-given ability to grasp the concept of eternity."3 While com monly accepted by scholars and laypersons alike, this notion is cu riously absent from the writings of the early church fathers4 as well as the major theological treatise of William Carey, the founder of the modern missionary movement.5 In fact modern scholars have suggested almost a dozen different interpretations for this verse. In Brian P. Gault is a Ph.D. student in Hebrew Bible and the Ancient Near East at Hebrew Union College—Jewish Institute of Religion, Cincinnati, Ohio. 1 Unless noted otherwise, all Scripture quotations are those of the present writer. 2 Don Richardson, Eternity in Their Hearts (Ventura, CA: Regal, 1981), 28. 3 Personal interview cited by Don Richardson, "Redemptive Analogy," in Perspec tives on the World Christian Movement, ed. Ralph D. Winter and Steven C. Hawthorne (Pasadena, CA: William Carey Library, 2000), 400. -

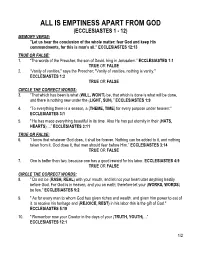

Is Emptiness Apart From

ALL IS EMPTINESS APART FROM GOD (ECCLESIASTES 1 - 12) MEMORY VERSE: "Let us hear the conclusion of the whole matter: fear God and keep His commandments, for this is man's all.” ECCLESIASTES 12:13 TRUE OR FALSE: 1. “The words of the Preacher, the son of David, king in Jerusalem.” ECCLESIASTES 1:1 TRUE OR FALSE 2. “Vanity of vanities," says the Preacher; "Vanity of vanities, nothing is vanity." ECCLESIASTES 1:2 TRUE OR FALSE CIRCLE THE CORRECT WORDS: 3. “That which has been is what (WILL, WON’T) be, that which is done is what will be done, and there is nothing new under the (LIGHT, SUN)." ECCLESIASTES 1:9 4. "To everything there is a season, a (THEME, TIME) for every purpose under heaven:" ECCLESIASTES 3:1 5. " He has made everything beautiful in its time. Also He has put eternity in their (HATS, HEARTS) ...” ECCLESIASTES 3:11 TRUE OR FALSE: 6. “I know that whatever God does, it shall be forever. Nothing can be added to it, and nothing taken from it. God does it, that men should fear before Him.” ECCLESIASTES 3:14 TRUE OR FALSE 7. One is better than two, because one has a good reward for his labor. ECCLESIASTES 4:9 TRUE OR FALSE CIRCLE THE CORRECT WORDS: 8. " Do not be (RASH, REAL) with your mouth, and let not your heart utter anything hastily before God. For God is in heaven, and you on earth; therefore let your (WORKS, WORDS) be few." ECCLESIASTES 5:2 9. " As for every man to whom God has given riches and wealth, and given him power to eat of it, to receive his heritage and (REJOICE, REST) in his labor-this is the gift of God." ECCLESIASTES 5:19 10. -

Ecclesiastes Song of Solomon

Notes & Outlines ECCLESIASTES SONG OF SOLOMON Dr. J. Vernon McGee ECCLESIASTES WRITER: Solomon. The book is the “dramatic autobiography of his life when he got away from God.” TITLE: Ecclesiastes means “preacher” or “philosopher.” PURPOSE: The purpose of any book of the Bible is important to the correct understanding of it; this is no more evident than here. Human philosophy, apart from God, must inevitably reach the conclusions in this book; therefore, there are many statements which seem to contra- dict the remainder of Scripture. It almost frightens us to know that this book has been the favorite of atheists, and they (e.g., Volney and Voltaire) have quoted from it profusely. Man has tried to be happy without God, and this book shows the absurdity of the attempt. Solomon, the wisest of men, tried every field of endeavor and pleasure known to man; his conclusion was, “All is vanity.” God showed Job, a righteous man, that he was a sinner in God’s sight. In Ecclesiastes God showed Solomon, the wisest man, that he was a fool in God’s sight. ESTIMATIONS: In Ecclesiastes, we learn that without Christ we can- not be satisfied, even if we possess the whole world — the heart is too large for the object. In the Song of Solomon, we learn that if we turn from the world and set our affections on Christ, we cannot fathom the infinite preciousness of His love — the Object is too large for the heart. Dr. A. T. Pierson said, “There is a danger in pressing the words in the Bible into a positive announcement of scientific fact, so marvelous are some of these correspondencies. -

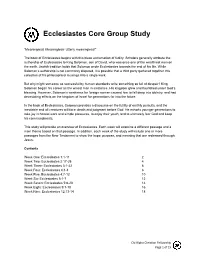

Ecclesiastes Core Group Study

Ecclesiastes Core Group Study “Meaningless! Meaningless! Utterly meaningless!” The book of Ecclesiastes begins with this bleak exclamation of futility. Scholars generally attribute the authorship of Ecclesiastes to King Solomon, son of David, who was once one of the wealthiest men on the earth. Jewish tradition holds that Solomon wrote Ecclesiastes towards the end of his life. While Solomon’s authorship is not commonly disputed, it is possible that a third party gathered together this collection of his philosophical musings into a single work. But why might someone so successful by human standards write something so full of despair? King Solomon began his career as the wisest man in existence. His kingdom grew and flourished under God’s blessing. However, Solomon’s weakness for foreign women caused him to fall deep into idolatry, and had devastating effects on the kingdom of Israel for generations far into the future. In the book of Ecclesiastes, Solomon provides a discourse on the futility of earthly pursuits, and the inevitable end all creatures will face: death and judgment before God. He exhorts younger generations to take joy in honest work and simple pleasures, to enjoy their youth, and to ultimately fear God and keep his commandments. This study will provide an overview of Ecclesiastes. Each week will examine a different passage and a main theme based on that passage. In addition, each week of the study will include one or more passages from the New Testament to show the hope, purpose, and meaning that are redeemed through Jesus. Contents Week One: Ecclesiastes 1:1-11 2 Week Two: Ecclesiastes 2:17-26 4 Week Three: Ecclesiastes 3:1-22 6 Week Four: Ecclesiastes 4:1-3 8 Week Five: Ecclesiastes 4:7-12 10 Week Six: Ecclesiastes 5:1-7 12 Week Seven: Ecclesiastes 5:8-20 14 Week Eight: Ecclesiastes 9:1-10 16 Week Nine: Ecclesiastes 12:13-14 18 Chi Alpha Christian Fellowship Page 1 of 19 Week One: Ecclesiastes 1:1-11 Worship Idea: Open in prayer, then sing some worship songs Opening Questions: 1. -

Righteousness and Wickedness in Ecclesiastes 7:15-18

Scholars Crossing SOR Faculty Publications and Presentations 1985 Righteousness and Wickedness in Ecclesiastes 7:15-18 Wayne Brindle Liberty University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/sor_fac_pubs Recommended Citation Brindle, Wayne, "Righteousness and Wickedness in Ecclesiastes 7:15-18" (1985). SOR Faculty Publications and Presentations. 105. https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/sor_fac_pubs/105 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholars Crossing. It has been accepted for inclusion in SOR Faculty Publications and Presentations by an authorized administrator of Scholars Crossing. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 242 DANIEL A. AUGSBURGER Andrews University Seminary Studies, Autumn 1985, Vol. 23, No.3, 243-257. Copyright rg 1985 by Andrews University Press. effort was not vain, however, for it was one of the greatest incentives for the spiritual descendants of Zwingli to love the Scripture and to be diligent students of its pages. It was also the root of one of the greatest privileges of modern man in many of the Christian lands RIGHTEOUSNESS AND WICKEDNESS IN religious freedom. ECCLESIASTES 7:15-18 WA YNE A. BRINDLE B. R. Lakin School of Religion Liberty University Lynchburg, Virginia 24506 Good and evil, righteousness and wickedness, virtue and vice-these are common subjects in the Scriptures. The poetical books, especially, are much concerned with the acts of righteous and unrighteous persons. Qoheleth, in Ecclesiastes, declares that "there is nothing better ... than to rejoice and to do good in one's lifetime" (3: 12, NASB). In fact, he concludes the book with the warning that "God will bring every act to judgment, everything which is hidden, whether it is good or evil" (12:14). -

Ecclesiastes “Life Under the Sun”

Ecclesiastes “Life Under the Sun” I. Introduction to Ecclesiastes A. Ecclesiastes is the 21st book of the Old Testament. It contains 12 chapters, 222 verses, and 5,584 words. B. Ecclesiastes gets its title from the opening verse where the author calls himself ‘the Preacher”. 1. The Septuagint (the translation of the Hebrew into the common language of the day, Greek) translated this word, Preacher, as Ecclesiastes and thus e titled the book. a. Ecclesiastes means Preacher; the Hebrew word “Koheleth” carries the menaing of preacher, teacher, or debater. b. The idea is that the message of Ecclesiastes is to be heralded throughout the world today. C. Ecclesiastes was written by Solomon. 1. Jewish tradition states Solomon wrote three books of the Bible: a. Song of Solomon, in his youth b. Proverbs, in his middle age years c. Ecclesiastes, when he was old 2. Solomon’s authorship had been accepted as authentic, until, in the past few hundred years, the “higher critics” have attempted to place the book much later and attribute it to someone pretending to be Solomon. a. Their reasoning has to do with a few words they believe to be of a much later usage than Solomon’s time. b. The internal evidence, however, strongly supports Solomon as the author. i. Ecc. 1:1 He calls himself the son of David and King of Jerusalem ii. Ecc. 1:12 Claims to be King over Israel in Jerusalem” iii. Only Solomon ruled over all Israel from Jerusalem; after his reign, civil war split the nation. Those in Jerusalem ruled over Judah. -

Ecclesiastes 1

International King James Version Old Testament 1 Ecclesiastes 1 ECCLESIASTES Chapter 1 before us. All is Vanity 11 There is kno remembrance of 1 ¶ The words of the Teacher, the former things, neither will there be son of David, aking in Jerusalem. any remembrance of things that are 2 bVanity of vanities, says the Teacher, to come with those that will come vanity of vanities. cAll is vanity. after. 3 dWhat profit does a man have in all his work that he does under the Wisdom is Vanity sun? 12 ¶ I the Teacher was king over Is- 4 One generation passes away and rael in Jerusalem. another generation comes, but ethe 13 And I gave my heart to seek and earth abides forever. lsearch out by wisdom concerning all 5 fThe sun also rises and the sun goes things that are done under heaven. down, and hastens to its place where This mburdensome task God has it rose. given to the sons of men by which to 6 gThe wind goes toward the south be busy. and turns around to the north. It 14 I have seen all the works that are whirls around continually, and the done under the sun. And behold, all wind returns again according to its is vanity and vexation of spirit. circuits. 15 nThat which is crooked cannot 7 hAll the rivers run into the sea, yet be made straight. And that which is the sea is not full. To the place from lacking cannot be counted. where the rivers come, there they re- 16 ¶ I communed with my own heart, turn again. -

Ecclesiastes – “It’S ______About _____”

“DISCOVERING THE UNREAD BESTSELLER” Week 18: Sunday, March 25, 2012 ECCLESIASTES – “IT’S ______ ABOUT _____” BACKGROUND & TITLE The Hebrew title, “___________” is a rare word found only in the Book of Ecclesiastes. It comes from a word meaning - “____________”; in fact, it’s talking about a “_________” or “_________”. The Septuagint used the Greek word “__________” as its title for the Book. Derived from the word “ekklesia” (meaning “assembly, congregation or church”) the title again (in the Greek) can simply be taken to mean - “_________/_________”. AUTHORSHIP It is commonly believed and accepted that _________authored this Book. Within the Book, the author refers to himself as “the son of ______” (Ecclesiastes 1:1) and then later on (in Ecclesiastes 1:12) as “____ over _____ in Jerusalem”. Solomon’s extensive wisdom; his accomplishments, and his immense wealth (all of which were God-given) give further credence to his work. Outside the Book, _______ tradition also points to Solomon as author, but it also suggests that the text may have undergone some later editing by _______ or possibly ____. SNAPSHOT OF THE BOOK The Book of Ecclesiastes describes Solomon’s ______ for meaning, purpose and satisfaction in life. The Book divides into three different sections - (1) the _____ that _______ is ___________ - (Ecclesiastes 1:1-11); (2) the ______ that everything is meaningless (Ecclesiastes 1:12-6:12); and, (3) the ______ or direction on how we should be living in a world filled with ______ pursuits and meaninglessness (Ecclesiastes 7:1-12:14). That last section is important because the Preacher/Teacher ultimately sees the emptiness and futility of all the stuff people typically strive for _____ from God – p______ – p_______ – p________ - and p________. -

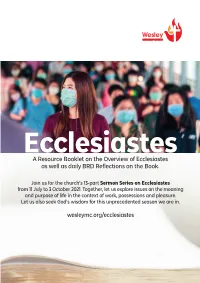

Ecclesiastes a Resource Booklet on the Overview of Ecclesiastes As Well As Daily BRD Reflections on the Book

Ecclesiastes A Resource Booklet on the Overview of Ecclesiastes as well as daily BRD Reflections on the Book. Join us for the church’s 13-part Sermon Series on Ecclesiastes from 11 July to 3 October 2021. Together, let us explore issues on the meaning and purpose of life in the context of work, possessions and pleasure. Let us also seek God’s wisdom for this unprecedented season we are in. wesleymc.org/ecclesiastes BIBLE READING DRIVE 2021 | Daily Reflections 1 contents LETTER FROM PASTOR-IN-CHARGE P3 ECCLESIASTES/OVERVIEW By Rev Raymond Fong, Pastor-in-Charge P4 SCHEDULE OF SERMONS ON ECCLESIASTES P15 Traditional and Prayer & Praise Services BIBLE READING DRIVE 2021 Daily Reflections on the Book of Ecclesiastes P16 Day 1 • Friday, 2 July P1 7 Day 2 • Saturday, 3 July P20 Day 3 • Sunday, 4 July P23 Day 4 • Monday, 5 July P26 Day 5 • Tuesday, 6 July P29 Day 6 • Wednesday, 7 July P32 Day 7 • Thursday, 8 July P34 Day 8 • Friday, 9 July P37 Day 9 • Saturday, 10 July P40 Day 10 • Sunday, 11 July P43 Day 11 • Monday, 12 July P46 Day 12 • Tuesday, 13 July P48 2 BIBLE READING DRIVE 2021 | Daily Reflections LETTER FROM PASTOR-IN-CHARGE My dear Wesleyan and friend I pray for the peace and protection of God to be with you in these trying times. You are dearly remembered in our prayers. I miss seeing you in person but I know God is watching over you as you continue to stay faithful to Him. We have begun a three-month sermon series on Ecclesiastes and we hope to glean godly wisdom with regard to the meaning and purpose of life, especially so in these uncertain times. -

Ecclesiastes Devotionals

Read Ecclesiastes 1 That which has been is that which will be, and that which has been done is that which will be done. so there is nothing new under the sun. Eccl 1:9 I was a freshman in college, when a new friend of mine introduced me to his new found source of cash. He was selling phone cards, which were really big at the time because you didn't have a large group of people with cell phones. The idea was not only to sell the phone cards, but to get other people to sell them. You would get a cut of the sales of the people you later recruited, and he had been making real money to prove it. My dad called it a pyramid scheme, and I didn't really know what that was. Eventually the money and the company dried up and I saw Dad was right. Years later someone offered me a chance to make money selling a larger variety of items. I quickly realized I was looking at the same pyramid scheme, just with different components. I remembered the first lesson and kept my money. The book of Ecclesiastes was written by Solomon in his later years. He had more wisdom than anyone who ever lived on the earth, and yet he still had plenty of unwise decisions scattered behind him. And one of the great warnings that Solomon gives is that there's nothing new under the sun. As the internet has become more a part of our lives, it has brought as many problems as solutions. -

The Bondage of Gangnam Style Ecclesiastes 5:8-20 What's The

The Bondage of Gangnam Style Ecclesiastes 5:8-20 What’s the Point!?! Sermon 08 Gangnam Style! That’s a hit song by South Korean musician, Psy and the first YouTube video to hit a billion views making it YouTube’s most watched video ever. We were trying to decide who had the most Gangnam Style on staff. What do you think? (Carson’s head on Psy’s body). Or? (Sarah Leafblad’s head on Psy’s body). But hands down, I thought this was best Grace Church Gangnam Style (Aiden Leafblad’s head on Psy’s body). What you may now know is that Gangnam Style is much more than a song. It refers to a lifestyle associated with the Gangnam district of Seoul. Gangnam is a 15-square-mile neighborhood that’s one of the wealthiest neighborhoods in the world. It has no equivalent in the U.S. The closest approximation would be Silicon Valley, Wall Street, Beverly Hills, Manhattan's Upper East Side, and Miami Beach all rolled into one. South Korea's richest and most influential companies are headquartered there. It’s wealthiest people and superclans live there, families who run companies like Samsung and Hyundai. 41% of attendees to the prestigious Seoul University come from Gangnam. Imagine if 41% of Harvard’s undergrads came from one neighborhood. Psy, the son of a wealthy Korean family, has seen "Gangnam Style" from the inside. He’s ridiculing the emptiness of Gangnam Style. Yet, the truth is, most people long for some level of Gangnam Style, failing to realize there’s a dark side, The Bondage of Gangnam Style.