EXIS-D-16-00039R2 Ti

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

4C Buried Secrets

R-0048 a reporter at laRgE bURiEd sEcrets How an Israeli billionaire wrested control of one of Africa’s biggest prizes. bY paTRick radden keefE 50 THE NEW YORKER, JULY 8 & 15, 2013 TNY—2013_07_08&15—PAGE 50—133SC.—Live art r23707—CritiCAL PHOTOGRAPH TO BE WATCHED THROUGHOUT THE ENTIRE PRESS run—pLEASE PULL KODAK APPROVAL PROOF F0R PRESS COLOR GUID- ANCE 4C ne of the world’s largest known de- As wealthy countries confront the posits of untapped iron ore is buried prospect of rapidly depleting natural re- insideO a great, forested mountain range in sources, they are turning, increasingly, the tiny West African republic of Guinea. to Africa, where oil and minerals worth In the country’s southeast highlands, far trillions of dollars remain trapped in the from any city or major roads, the Siman- ground. By one estimate, the continent dou Mountains stretch for seventy miles, holds thirty per cent of the world’s min- looming over the jungle floor like a giant eral reserves. Paul Collier, who runs the dinosaur spine. Some of the peaks have Center for the Study of African Econo- nicknames that were bestowed by geolo- mies, at Oxford, has suggested that “a gists and miners who have worked in the new scramble for Africa” is under way. area; one is Iron Maiden, another Metal- Bilateral trade between China and Af- lica. Iron ore is the raw material that, once rica, which in 2000 stood at ten billion smelted, becomes steel, and the ore at Si- dollars, is projected to top two hundred mandou is unusually rich, meaning that billion dollars this year. -

New Records of the Togo Toad, Sclerophrys Togoensis, from South-Eastern Ivory Coast

Herpetology Notes, volume 12: 501-508 (2019) (published online on 19 May 2019) New records of the Togo Toad, Sclerophrys togoensis, from south-eastern Ivory Coast Basseu Aude-Inès Gongomin1, N’Goran Germain Kouamé1,*, and Mark-Oliver Rödel2 Abstract. Reported are new records of the forest toad, Sclerophrys togoensis, from south-eastern Ivory Coast. A small population was found in the rainforest of Mabi and Yaya Classified Forests. These forests and Taï National Park in the western part of the country are the only known and remaining Ivorian habitats of this species. Sclerophrys togoensis is confined to primary and slightly degraded rainforest. Known sites should be urgently and effectively protected from further forest loss. Keywords. Amphibia, Anura, Bufonidae, Conservation, Distribution, Mabi/Yaya Classified Forests, Upper Guinea forest Introduction In Ivory Coast the known records of S. togoensis are from the Cavally and Haute Dodo Classified Forests The toad Sclerophrys togoensis (Ahl, 1924) has been (Rödel and Branch, 2002), and the Taï National Park described from Bismarckburg in Togo (Ahl, 1924). Apart and its surroundings (e.g. Ernst and Rödel, 2006; Hillers from a parasitological study (Bourgat, 1978), no recent et al., 2008), all situated in the westernmost part of the records are known from that country (Ségniagbeto et al., country (Fig. 1). During a decade of conflict, both 2007; Hillers et al., 2009). Further records have been classified forests have been deforested (P.J. Adeba, pers. published from southern Ghana (Kouamé et al., 2007; comm.), thus restricting the species known Ivorian range Hillers et al., 2009), western Ivory Coast (e.g. -

The Politics Behind the Ebola Crisis

The Politics Behind the Ebola Crisis Africa Report N°232 | 28 October 2015 International Crisis Group Headquarters Avenue Louise 149 1050 Brussels, Belgium Tel: +32 2 502 90 38 Fax: +32 2 502 50 38 [email protected] Table of Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................... i Recommendations..................................................................................................................... iii I. Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 1 II. Pre-epidemic Situation ..................................................................................................... 3 A. Liberia ........................................................................................................................ 4 B. Sierra Leone ............................................................................................................... 5 C. Guinea ........................................................................................................................ 7 III. How Misinformation, Mistrust and Myopia Amplified the Crisis ................................... 8 A. Misinformation and Hesitation ................................................................................. 8 B. Extensive Delay and its Implications ........................................................................ 9 C. Quarantine and Containment ................................................................................... -

Unintended Consequences of the 'Bushmeat Ban' in West Africa During the 2013–2016 Ebola Virus Disease Epidemic

King’s Research Portal DOI: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.12.028 Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Link to publication record in King's Research Portal Citation for published version (APA): Bonwitt, J., Dawson, M., Kandeh, M., Ansumana, R., Sahr, F., Brown, H., & Kelly, A. H. (2018). Unintended consequences of the ‘bushmeat ban’ in West Africa during the 2013–2016 Ebola virus disease epidemic. Social Science & Medicine, 200, 166-173. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.12.028 Citing this paper Please note that where the full-text provided on King's Research Portal is the Author Accepted Manuscript or Post-Print version this may differ from the final Published version. If citing, it is advised that you check and use the publisher's definitive version for pagination, volume/issue, and date of publication details. And where the final published version is provided on the Research Portal, if citing you are again advised to check the publisher's website for any subsequent corrections. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the Research Portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognize and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. •Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the Research Portal for the purpose of private study or research. •You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain •You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the Research Portal Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. -

Fighting Ebola: a Strategy for Action

FIGHTING EBOLA: A STRATEGY FOR ACTION Vera Songwe, Nonresident Senior Fellow, Africa Growth Initiative THE PRIORITY Despite these overwhelming numbers, prog- ress is being made in the fight against these African populations continue to suffer under diseases. For example, malaria mortality rates in the heavy burden of disease despite overall sus- children in Africa were reduced by an estimat- tained increases in income levels over the last ed 54 percent between 2002 and 2012. Since decade. Three major diseases are among those 2000, there has been a 49 percent reduction responsible for health crises: malaria, HIV/AIDS in the overall malaria mortality rates in Africa. and tuberculosis, and, in 2014, the Ebola virus For HIV, by the end of 2012, about 68 percent emerged as a fourth virus with pandemic po- of eligible persons were receiving antiretroviral tential. treatment, an increase of more than 90 percent since 2009 (UNAIDS 2013). In 2012, for example, 80 percent of the estimat- ed 207 million malaria cases worldwide were However, 2014 in West Africa will be remem- found in Africa, and 90 percent of the estimat- bered not for progress made in combatting in- ed 627,000 global malaria deaths occurred in fectious diseases but as the year the Ebola virus Africa. On average, malaria kills a child every crippled three countries on the continent and minute, of which 90 percent occur among Afri- inflicted economic damage to many others. can children. Malaria-related anemia is estimat- The 20th Ebola outbreak globally has captured ed to cause thousands of deaths a year—and the attention of the world like none of the oth- for countries with endemic malaria, it is estimat- ers that have preceded it and like no other dis- ed that there is a 1.3 percentage point loss in ease has in recent history. -

SHEINI+FISCALS+PAPER.Pdf

NOVEMBER, 2016 Avenue D, Hse. No. 119 D, North Legon P. O. Box CT2121 Cantonment, A POLICY BRIEF ON Accra-Ghana Tel: 030-290 0730 THE POTENTIAL FISCAL CONTRIBUTION facebook: Africa Centre for Energy Policy SPONSORED BY: OF THE SHEINI IRON ORE DEPOSITS IN twitter@AcepPower www.acepghana.com NORTHERN GHANA Executive Summary In the wake of increasing global economic challenges amidst unprecedented political events that may have significant impact on the world economies, Ghana is again blessed with an iron ore mine which is yet to be developed. The mine has the potential to expand the country’s economic progress and have trickling down effects of social progress and sustainable development for its peoples. It therefore becomes imperative to understand the extent of fiscal impacts that Ghana’s Sheini iron ore project is likely to bring. It is against this backdrop that the Africa Centre for Energy Policy (ACEP), through its partnership with WACAM under the auspices of OSIWA, undertook this fiscal benchmarking study. The approach to the study was quantitative. Using an excel fiscal model, the Sheini iron ore project was situated within the geological and project context of Guinea’s Simandou iron ore project to compare Ghana’s mining fiscal policy against the fiscal provisions of the contract between the Government of Guinea and Simfer S.A. The purpose was to determine the level of fiscal convergence between the two projects and use findings as an important guide for improving on the fiscal take from Ghana’s Sheini iron ore project. The following were the key findings about the competitiveness of Ghana’s mining fiscal terms and how equitable they are in ensuring that the government and its people benefit from the mining sector: From Government Perspective 1. -

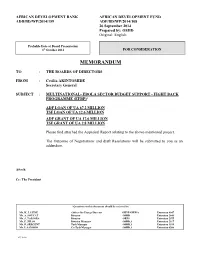

Appraisal Report Relating to the Above-Mentioned Project

AFRICAN DEVELOPMENT BANK AFRICAN DEVELOPMENT FUND ADB/BD/WP/2014/159 ADF/BD/WP/2014/108 26 September 2014 Prepared by: OSHD Original: English Probable Date of Board Presentation 1st October 2014 FOR CONSIDERATION MEMORANDUM TO : THE BOARDS OF DIRECTORS FROM : Cecilia AKINTOMIDE Secretary General SUBJECT : MULTINATIONAL- EBOLA SECTOR BUDGET SUPPORT - FIGHT BACK PROGRAMME (EFBP)* ADF LOAN OF UA 67.2 MILLION TSF LOAN OF UA 12.6 MILLION ADF GRANT OF UA 17.6 MILLION TSF GRANT OF UA 2.8 MILLION Please find attached the Appraisal Report relating to the above-mentioned project. The Outcome of Negotiations and draft Resolutions will be submitted to you as an addendum. Attach: Cc: The President *Questions on this document should be referred to: Mr. K. J. LITSE Officer-In-Charge/Director ORVP/ORWA Extension 4047 Ms. A. SOUCAT Director OSHD Extension 2046 Mr. S. TAPSOBA Director ORFS Extension 2075 Mr. F. ZHAO Division Manager OSHD.3 Extension 2117 Mr. F. SERGENT Task Manager OSHD.3 Extension 1519 Mr. I. SANOGO Co-Task Manager OSHD.3 Extension 4206 SCCD:F.S. AFRICAN DEVELOPMENT BANK GROUP MUTINATIONAL EBOLA SECTOR BUDGET SUPPORT- FIGHT BACK PROGRAMME (EFBP) COUNTRIES: THE REPUBLICS OF CÔTE D’IVOIRE, GUINEA, LIBERIA AND SIERRA LEONE APPRAISAL REPORT Date: September 2014 Team Leader: Fabrice Sergent, Chief Health Analyst, OSHD 3 Co-Team Leader: I. Sanogo, Principal Health Specialist, OSHD.3 Team Members: Ms. M. Sharan, Senior Gender Specialist, OSHD.3 Mr. V. Durairaj, Chief Health Insurance & Social protection officer, OSHD.3 Mr. J. Murara, Chief Poverty Alleviation Officer, OSHD.1 Ms. C. -

Key Biodiversity Areas Identification in the Upper Guinea Forest Biodiversity Hotspot

JoTT COMMUNI C ATION 4(8): 2745–2752 Key Biodiversity Area Special Series Key Biodiversity Areas identification in the Upper Guinea forest biodiversity hotspot O.M.L. Kouame 1, N. Jengre 2, M. Kobele 3, D. Knox 4, D.B. Ahon 5, J. Gbondo 6, J. Gamys 7, W. Egnankou 8, D. Siaffa 9, A. Okoni-Williams 10 & M. Saliou 11 1 4744 Kenmore ave # 202, Alexandria, VA, 22304, USA 2 Hse No. 36 Abotsi Street, East Legon P. O. Box KA 9714, Airport Accra 3,11 Guinee Ecologie, 210 DI 501 Dixinn, PoB:3266 Conakry, Guinea 4 The Wharton School, University of Pennsylvania, 3730 Walnut Street, Philadelphia, PA 19104, USA 5 22 BP 918 Abidjan 22 Côte d’Ivoire 6 150 Princeton Arms South II, East Windsor, N.J 08512, USA 7 Conservation International-Liberia, Back Road, Congo Town, Monrovia, Liberia 8 SOS-FORETS, 22 BP 918 Abidjan 22 Côte d’Ivoire 9 11B Becklyn Drive, Off Main Motor Road, Congo Cross, Freetown, Sierra Leone 10 Fourah Bay College, University of Sierra Leone PMB Freetown, Sierra Leone Email: 1 [email protected] (corresponding author), 2 [email protected], 3 [email protected], 4 [email protected], 5 [email protected], 6 [email protected], 7 [email protected], 8 [email protected], 9 [email protected], 10 [email protected], 11 [email protected] Date of publication (online): 06 August 2012 Abstract: Priority-setting approaches and tools are commons ways to support the Date of publication (print): 06 August 2012 rapid extinction of species and their habitats and the effective allocation of resources ISSN 0974-7907 (online) | 0974-7893 (print) for their conservation. -

West Africa's Mining Industry

West Africa’s mining industry A rising mining market emerges in a challenging global context TABLE OF CONTENTS Ghana.......................................................p116 This report was researched and prepared by Mali...........................................................p122 Global Business Reports (www.gbreports.com) for Guinea.......................................................p126 Engineering & Mining Journal. Editorial researched and written by Ana Maria Miclea and Razvan Isac. For more details, please contact [email protected]. Cover photo courtesy of Engineers & Planners. A REPORT BY GBR FOR E&MJ JUNE 2014 MINING IN GHANA Ghana West Africa’s most revered mining jurisdiction By now, the fact that Ghana is West Af- neighboring countries, nor is it dramatically to successfully leverage the foreign invest- rica’s most mature and developed mining richer in resources than other promising ju- ments made into Ghana’s mining industry jurisdiction should not be news to any se- risdictions such as Cote D’Ivoire or Burkina in recent times. rious, informed mining stakeholder. More- Faso. Although its 539 km coastline gives In fact, Rocksure International took only over, the fact that Ghanaian mining is it the edge against countries such as Mali, five years to go from an equipment rental virtually synonymous with Ghanaian gold this asset can hardly be considered a deci- company to a full-fledged mining contrac- mining should not startle anyone either. sive differentiator in a region where Togo, tor, with over 200 staff. “It has been a From the distant times of the legendary Benin, The Ivory Coast, Guinea, Sierra Le- very exciting journey so far […] Rocksure Ashanti Kings and their gold, to present- one, and Liberia also have ocean-access. -

CONSERVATION of the CRITICALLY ENDANGERED TOGO SLIPPERY FROG ( Conraua Derooi ), in EASTERN GHANA

CONSERVATION OF THE CRITICALLY ENDANGERED TOGO SLIPPERY FROG ( Conraua derooi ), IN EASTERN GHANA Submitted by Ofori-Boateng, C., A. Damoah, G.B. Adum, S. Nsiah, E. Nkrumah and D. Saykay-Tuabeng E-mail: [email protected]. Tel: +233 (0)243038771 April 2012 CONSERVATION OF THE CRITICALLY ENDANGERED TOGO SLIPPERY FROG ( Conraua derooi ), IN EASTERN GHANA CLP project ID: 0143510 This project aimed at protecting the last known viable population of a Critically Endangered frog (the Togo slippery; Conraua derooi ) in Eastern Ghana Project duration: August 2010 – April 2011 Author (s) Ofori-Boateng, C., A. Damoah, G.B. Adum, S. Nsiah, E. Nkrumah and D. Saykay-Tuabeng [email protected] ©April 2012 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT We thank the Forestry Commission of Ghana for permission to carry out this research and conservation work in the Atewa Mountains. We are very grateful to Mr. Moses Sam, (regional manager, Ghana Wildlife Division offices in the western and central regions of Ghana) for supporting this project from the onset. We are thankful to several community members for their help and enthusiasm to promote conservation in their respective communities. Mr. Duodu assisted with our community entry and meeting planning in Sagyimase village. Mr. Mike Ofosu-Takyi provided accommodation for the team members anytime we were near Kibi township. We are also grateful to Mr. Philip Amankwah, Mr. Ibrahim Entsi, Antwi Kwame Prosper and several students and community members who participated in our field work. This work was funded by a future conservationist award from the Conservation Leadership Program (CLP). We are particularly grateful to various help provided by the CLP team particularly, Julie, Stuart, Kiragu and Robyn. -

Exploitation of Bats for Bushmeat and Medicine

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Springer - Publisher Connector Chapter 12 Exploitation of Bats for Bushmeat and Medicine Tammy Mildenstein, Iroro Tanshi and Paul A. Racey Abstract Bat hunting for consumption as bushmeat and medicine is widespread and affects at least 167 species of bats (or c. 13 % of the world’s bat species), in Africa, Asia, across the islands of Oceania, and to a lesser extent in Central and South America. Hunting is particularly prevalent among the large-bodied fruit bats of the Old World tropics, where half (50 %, 92/183) the extant species in the family Pteropodidae are hunted. Pteropodids that are hunted are six times more likely to be Red Listed as threatened: 66 % of species in IUCN threatened categories (CR, EN, VU, NT), compared to 11 % of species in the ‘Least Concern’ (LC) category. However, there still appears to be an information gap at the international level. One third of the hunted species on the Red List are not considered threatened by that hunting, and nearly a quarter of the bat species included in this review are not listed as hunted in IUCN Red List species accounts. This review has resulted in a com- prehensive list of hunted bats that doubles the number of species known from either the IUCN Red List species accounts or a questionnaire circulated in 2004. More research is needed on the impacts of unregulated hunting, as well as on the sustain- ability of regulated hunting programs. In the absence of population size and growth data, legislators and managers should be precautionary in their attitude towards T. -

Paysage Transfrontalier De La Forêt De Haute Guinée

ÉTUDE DE CAS Application coordonnée et collaborative de la hiérarchie d’atténuation dans les paysages complexes à usages multiples en Afrique: Paysage transfrontalier de la forêt de Haute Guinée Opportunités et défis pour le maintien d’un paysage forestier connecté face aux pressions du développement Rapport préparé par Fauna & Flora International © Fauna & Flora International 2021 Fauna & Flora International (FFI) protège les espèces et les écosystèmes menacés dans le monde entier, en choisissant des solutions durables, fondées sur des données scientifiques solides et tenant compte des besoins humains. Fondée en 1903, FFI est l’organisme international de conservation le plus ancien au monde et une organisation caritative enregistrée. Pour plus d’informations, voir : www.fauna-flora.org La reproduction de cette publication à des fins éducatives ou non lucratives est autorisée sans autorisation écrite préalable du détenteur des droits d’auteur, à condition que la source soit dûment citée. La réutilisation de toute photographie ou figure est soumise à l’autorisation écrite préalable des détenteurs des droits d’origine. Aucune utilisation de cette publication ne peut être faite à des fins de revente ou à toute autre fin commerciale sans l’autorisation écrite préalable de FFI. Les demandes d’autorisation, accompagnées d’une déclaration sur l’objet et l’étendue de la reproduction, doivent être envoyées par courrier électronique à [email protected] ou par courrier à Communications, Fauna & Flora International, The David Attenborough Building, Pembroke Street, Cambridge CB2 3QZ, U.K. Photo de couverture: Jeremy Holden/FFI Conception de la couverture: Dan Barrett, Brandman Auteurs Principaux: Nicky Jenner, Michelle Villeneuve, Koighae Toupou, Erin Parham, Angelique Todd, Anna Lyons and Pippa Howard.