Steward Priority Zones

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Table 7: Species Changing IUCN Red List Status (2014-2015)

IUCN Red List version 2015.4: Table 7 Last Updated: 19 November 2015 Table 7: Species changing IUCN Red List Status (2014-2015) Published listings of a species' status may change for a variety of reasons (genuine improvement or deterioration in status; new information being available that was not known at the time of the previous assessment; taxonomic changes; corrections to mistakes made in previous assessments, etc. To help Red List users interpret the changes between the Red List updates, a summary of species that have changed category between 2014 (IUCN Red List version 2014.3) and 2015 (IUCN Red List version 2015-4) and the reasons for these changes is provided in the table below. IUCN Red List Categories: EX - Extinct, EW - Extinct in the Wild, CR - Critically Endangered, EN - Endangered, VU - Vulnerable, LR/cd - Lower Risk/conservation dependent, NT - Near Threatened (includes LR/nt - Lower Risk/near threatened), DD - Data Deficient, LC - Least Concern (includes LR/lc - Lower Risk, least concern). Reasons for change: G - Genuine status change (genuine improvement or deterioration in the species' status); N - Non-genuine status change (i.e., status changes due to new information, improved knowledge of the criteria, incorrect data used previously, taxonomic revision, etc.); E - Previous listing was an Error. IUCN Red List IUCN Red Reason for Red List Scientific name Common name (2014) List (2015) change version Category Category MAMMALS Aonyx capensis African Clawless Otter LC NT N 2015-2 Ailurus fulgens Red Panda VU EN N 2015-4 -

4C Buried Secrets

R-0048 a reporter at laRgE bURiEd sEcrets How an Israeli billionaire wrested control of one of Africa’s biggest prizes. bY paTRick radden keefE 50 THE NEW YORKER, JULY 8 & 15, 2013 TNY—2013_07_08&15—PAGE 50—133SC.—Live art r23707—CritiCAL PHOTOGRAPH TO BE WATCHED THROUGHOUT THE ENTIRE PRESS run—pLEASE PULL KODAK APPROVAL PROOF F0R PRESS COLOR GUID- ANCE 4C ne of the world’s largest known de- As wealthy countries confront the posits of untapped iron ore is buried prospect of rapidly depleting natural re- insideO a great, forested mountain range in sources, they are turning, increasingly, the tiny West African republic of Guinea. to Africa, where oil and minerals worth In the country’s southeast highlands, far trillions of dollars remain trapped in the from any city or major roads, the Siman- ground. By one estimate, the continent dou Mountains stretch for seventy miles, holds thirty per cent of the world’s min- looming over the jungle floor like a giant eral reserves. Paul Collier, who runs the dinosaur spine. Some of the peaks have Center for the Study of African Econo- nicknames that were bestowed by geolo- mies, at Oxford, has suggested that “a gists and miners who have worked in the new scramble for Africa” is under way. area; one is Iron Maiden, another Metal- Bilateral trade between China and Af- lica. Iron ore is the raw material that, once rica, which in 2000 stood at ten billion smelted, becomes steel, and the ore at Si- dollars, is projected to top two hundred mandou is unusually rich, meaning that billion dollars this year. -

New Records of the Togo Toad, Sclerophrys Togoensis, from South-Eastern Ivory Coast

Herpetology Notes, volume 12: 501-508 (2019) (published online on 19 May 2019) New records of the Togo Toad, Sclerophrys togoensis, from south-eastern Ivory Coast Basseu Aude-Inès Gongomin1, N’Goran Germain Kouamé1,*, and Mark-Oliver Rödel2 Abstract. Reported are new records of the forest toad, Sclerophrys togoensis, from south-eastern Ivory Coast. A small population was found in the rainforest of Mabi and Yaya Classified Forests. These forests and Taï National Park in the western part of the country are the only known and remaining Ivorian habitats of this species. Sclerophrys togoensis is confined to primary and slightly degraded rainforest. Known sites should be urgently and effectively protected from further forest loss. Keywords. Amphibia, Anura, Bufonidae, Conservation, Distribution, Mabi/Yaya Classified Forests, Upper Guinea forest Introduction In Ivory Coast the known records of S. togoensis are from the Cavally and Haute Dodo Classified Forests The toad Sclerophrys togoensis (Ahl, 1924) has been (Rödel and Branch, 2002), and the Taï National Park described from Bismarckburg in Togo (Ahl, 1924). Apart and its surroundings (e.g. Ernst and Rödel, 2006; Hillers from a parasitological study (Bourgat, 1978), no recent et al., 2008), all situated in the westernmost part of the records are known from that country (Ségniagbeto et al., country (Fig. 1). During a decade of conflict, both 2007; Hillers et al., 2009). Further records have been classified forests have been deforested (P.J. Adeba, pers. published from southern Ghana (Kouamé et al., 2007; comm.), thus restricting the species known Ivorian range Hillers et al., 2009), western Ivory Coast (e.g. -

Keeping Global Warming Within 1.5°C Constrains Emergence of Aridification

` Keeping global warming within 1.5°C constrains emergence of aridification Chang-Eui Park1, Su-Jong Jeong1*, Manoj Joshi2, Timothy J. Osborn2, Chang-Hoi Ho3, Shilong Piao4,5,6, Deliang Chen7, Junguo Liu1, Hong Yang8,9, Hoonyoung Park3, Baek-Min Kim10, Song Feng11 1School of Environmental Science and Engineering, Southern University of Science and Technology (SUSTech), Shenzhen, China 2Climatic Research Unit, School of Environmental Sciences, University of East Anglia, Norwich, NR4 7TJ, UK 3School of Earth and Environmental Sciences, Seoul National University, Seoul, Republic of Korea 4Key Laboratory of Alpine Ecology and Biodiversity, Institute of Tibetan Plateau Research, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, China 5Sino-French Institute for Earth System Science, College of Urban and Environmental Sciences, Peking University, Beijing 100871, China 6Center for Excellence in Tibetan Earth Science, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100085, China 7Department of Earth Sciences, University of Gothenburg, Gothenburg, Sweden 8EAWAG, Swiss Federal Institute of Aquatic Science and Technology, Dübendorf, Switzerland 9Faculty of Sciences, University of Basel, Basel, Switzerland 10Korea Polar Research Institution, Inchon, Korea 11Department of Geosciences, University of Arkansas, Fayetteville, 72701, AR, USA Nature Climate Change (Accepted) *Corresponding author: Prof. Su-Jong Jeong, School of Environmental Science and Engineering, South University of Science and Technology of China, Shenzhen 518055, Guangdong, China ([email protected]) ` Aridity – the ratio of atmospheric water supply (precipitation; P) to demand (potential evapotranspiration; PET) – is projected to decrease (i.e., become drier) as a consequence of anthropogenic climate change, aggravating land degradation and desertification1-6. However, the timing of significant aridification relative to natural variability – defined here as the time of emergence for aridification (ToEA) – is unknown, despite its importance in designing and implementing mitigation policy7-10. -

The Politics Behind the Ebola Crisis

The Politics Behind the Ebola Crisis Africa Report N°232 | 28 October 2015 International Crisis Group Headquarters Avenue Louise 149 1050 Brussels, Belgium Tel: +32 2 502 90 38 Fax: +32 2 502 50 38 [email protected] Table of Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................... i Recommendations..................................................................................................................... iii I. Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 1 II. Pre-epidemic Situation ..................................................................................................... 3 A. Liberia ........................................................................................................................ 4 B. Sierra Leone ............................................................................................................... 5 C. Guinea ........................................................................................................................ 7 III. How Misinformation, Mistrust and Myopia Amplified the Crisis ................................... 8 A. Misinformation and Hesitation ................................................................................. 8 B. Extensive Delay and its Implications ........................................................................ 9 C. Quarantine and Containment ................................................................................... -

Government of the Republic of Sierra Leone Bumbuna Hydroelectric

Government of the Republic of Sierra Leone Ministry of Energy and Power Public Disclosure Authorized Bumbuna Hydroelectric Project Environmental Impact Assessment Draft Final Report - Appendices Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized January 2005 Public Disclosure Authorized in association with BMT Cordah Ltd Appendices Document Orientation The present EIA report is split into three separate but closely related documents as follows: Volume1 – Executive Summary Volume 2 – Main Report Volume 3 – Appendices This document is Volume 3 – Appendices. Nippon Koei UK, BMT Cordah and Environmental Foundation for Africa i Appendices Glossary of Acronyms AD Anno Domini AfDB African Development Bank AIDS Auto-Immune Deficiency Syndrome ANC Antenatal Care BCC Behavioural Change Communication BHP Bumbuna Hydroelectric Project BWMA Bumbuna Watershed Management Authority BOD Biochemical Oxygen Demand BP Bank Procedure (World Bank) CBD Convention on Biodiversity CHC Community Health Centre CHO Community Health Officer CHP Community Health Post CLC Community Liaison Committee COD Chemical Oxygen Demand dbh diameter at breast height DFID Department for International Development (UK) DHMT District Health Management Team DOC Dissolved Organic Carbon DRP Dam Review Panel DUC Dams Under Construction EA Environmental Assessment ECA Export Credit Agency EFA Environmental Foundation for Africa EHS Environment, Health and Safety EHSO Environment, Health and Safety Officer EIA Environmental Impact Assessment EMP Environmental Management Plan EPA -

Edmonton Valley Zoo

ABOVEEdmonton Valley Zoo “When you realize the value of all life, you dwell less on what is past and concentrate on the preservation of the future.” ~ Dian Fossey Immersive landscapes are those in which animals and humans alike are enveloped by a common habitat. This approach erases the boundaries and hierarchical divisions between animals and visitors found at conventional zoos. By engaging animals on their own terms and in their own habitats, visitors are better able to understand the high degree of interconnectivity between themselves, the animals they are viewing, and the world around them. Children and adults perceive and engage the world in very different ways. At an elemental level, children operate at a very different scale than their adult counterparts. Unlike adults, children also tend to learn about the world and their place in it with a high degree of physicality: through play. Using immersive landscapes and a ‘children’s geography’ as points of departure, the master plan for the Children’s Precinct pursues four primary gestures of spatial engagement as means of defining a new conceptual framework for the Zoo: Under, Between, On, and Above. These abstract experiential types speak to a wide range of possible means of bodily relation to a given landscape and simultaneously sponsor play as a primary mechanism for engaging that landscape. Building on the master plan for the Edmonton Valley Zoo Children’s precinct, this project develops one aspect of that proposal - the ‘Above Zone’ - as a discrete immersive experience. CONCEPTUAL CHILDREN’S EXPERIENTIAL SPATIAL CORE SUPPORTING FRAMEWORK GEOGRAPHY TOUCHSTONES ARCHETYPES SPECIES SPECIES The Above Building is the first project to be delivered by the Edmonton Valley Zoo based on its 2014 master plan. -

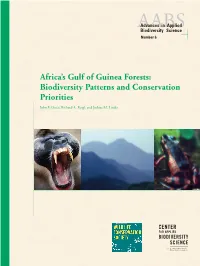

Africa's Gulf of Guinea Forests: Biodiversity Patterns and Conservation Priorities

Advances in Applied Biodiversity Science, no. 6 AABSAdvances in Applied Biodiversity Science Number 6 Africa’s Gulf of Guinea Forests: Africa’s Gulf of Guinea Forests:Biodiversity Patterns and Conservation Africa’s Biodiversity Patterns and Conservation Priorities John F. Oates, Richard A. Bergl, and Joshua M. Linder Priorities C Conservation International ONSERVATION 1919 M Street, NW, Suite 600 Washington, DC 20036 TEL: 202-912-1000 FAX: 202-912-0772 I NTERNATIONAL ISBN 1-881173-82-8 WEB: www.conservation.org 9 0 0 0 0> www.biodiversityscience.org 9781881173823 About the Authors John F. Oates is a CABS Research Fellow, Professor of Anthropology at Hunter College, City University of New York (CUNY), and a Senior Conservation Advisor to the Africa program of the Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS). He is cur- rently advising WCS on biodiversity conservation projects in eastern Nigeria and western Cameroon. Dr. Oates has conducted research on the ecology of forest primates in Africa and Asia since 1966, and has assisted with the development of rainforest protected areas in South India and West Africa. He has published extensively on primate biology and conservation and, as an active member of the IUCN-SSC Primate Specialist Group, has compiled conservation action plans for African primates. He holds a PhD from the University of London. Richard A. Bergl is a doctoral student in anthropology at the CUNY Graduate Center, in the graduate training program of the New York Consortium in Evolutionary Primatology (NYCEP). He is currently conducting research into the population and habitat viability of the Cross River gorilla (Gorilla gorilla diehli) in Nigeria and Cameroon. -

Regional Bureau for West Africa (ODD)

Regional Bureau for West Africa (ODD) Benin Burkina Faso Cameroon Central African Republic Chad Côte d’Ivoire Gambia Ghana Guinea Guinea-Bissau Liberia Mali Mauritania Niger São Tomé & Principe Senegal Sierra Leone Togo Regional Bureau for West Africa (ODD) The regional bureau for West Africa (ODD) includes country offices in 18 countries: Benin, Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Central African Republic, Chad, Côte d'Ivoire, Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Liberia, Mali, Mauritania, Niger, São Tomé and Principe, Senegal, Sierra Leone, and Togo. Expected Operational Trends in 2011 The West Africa region has high levels of food insecurity and malnutrition rates in a context characterized by chronic poverty, often compounded by political instability and natural disasters. Even in the post-harvest period, approximately half of all ODD countries have acute malnutrition rates among children under 5 that exceed the 10 percent threshold, thus classified as serious; these figures generally rise during the annual lean season when food stocks are depleted and survival strategies are exhausted. Given the region's fragility and susceptibility to natural disasters, insecurity and conflicts, the major WFP commitment for 2011 is to mitigate the impact of shocks on the most vulnerable. High priority is placed on nutrition asset preservation, the promotion of community-level resilience and the development of safety nets and social protection mechanisms alongside immediate life-saving assistance. The use of existing mechanisms such as advance financing and the forward purchase facility will be further promoted to ensure timely and optimal utilization of resources. Expected Major Opportunities and Challenges Natural disasters most affecting the region include droughts, floods and locust invasions. -

Upper Guinea Special Liberia and Sierra Leone Tour Leaflet 2023

BIRDING AFRICA THE AFRICA SPECIALISTS Upper Guinea Special Liberia and Sierra Leone Tour Leaflet 2023 Rufous Fishing Owl © Tertius Gous 5 – 12 January 2023 (Liberia) 12 – 20 January 2023 (Sierra Leone) Upper Guinea Special 2023 BIRDING Tour leader: Michael Mills AFRICA THE AFRICA SPECIALISTS Birding Africa Tour Summary Tour Africa Birding Summary Tour Africa Birding Specials in comfort • Numerous Upper Guinea Specials: Black-headed Rufous Warbler, Yellow-bearded Greenbul, Rufous Fishing Owl, Emerald Starling, Gola Malimbe • Easy access to Sierra Leone Prinia Yellow-bearded Greenbul © Tertius Gous • No camping required Our Upper Guinea Special tour is one of several White-crested Tiger Heron, African Pitta, Yellow- African tours that we have pioneered, and puts the headed Picathartes, Emerald Starling, Crimson comfort back into birding this little-known region. Seedcracker, Turati's Boubou and Togo Paradise Emerald Starling © Tertius Gous Michael’s incredible focus, dedication and ability Gone are the tough hikes and rough camping Whydah. to locate and show Africa's toughest birds is required on other tours to Sierra Leone, without probably unequalled. He has led dozens of tours compromising on the birds. across the continent and his experience in locating Tour Focus birds on just the soft est of calls or briefest of views Our tour, uniquely, combines the best of Liberia impresses those who travelled with him. and Sierra Leone, in reasonable comfort. Sturdy Th is tour will provide a good chance to see most of 4x4s are used throughout and all nights are the Upper Guinea forest specials. It is heavily bird Dates (2023) accommodated in hotels or guest houses, with no focused although we may see several species of camping required. -

Perspectives of Land Evaluation of Floodplains Under Conditions of Aridification Based on the Assessment of Ecosystem Services

DOI: 10.15201/hungeobull.69.3.1Lóczy, D. et al. HungarianHungarian Geographical Geographical Bulletin Bulletin 69 (2020) 69 2020 (3) 227–243. (3) 227–243.227 Perspectives of land evaluation of floodplains under conditions of aridification based on the assessment of ecosystem services Dénes LÓCZY1, Gergely TÓTH2, Tamás HERMANN2, Marietta REZSEK3, Gábor NAGY1, József DEZSŐ1, Ali SALEM3,4, Péter GYENIZSE1, Anne GOBIN5 and Andrea VACCA6 Abstract Global climate change has discernible impacts on the quality of the landscapes of Hungary. Only a dynamic and spatially differentiated land evaluation methodology can properly reflect these changes. The provision level, rate of transformation and spatial distribution of ecosystem services (ESs) are fundamental properties of landscapes and have to be integral parts of an up-to-date land evaluation. For agricultural land capability assessment soil fertility is a major supporting ES, directly associated with climate change through greenhouse gas emissions and carbon sequestration as regulationg services. Since for Hungary aridification is the most severe consequence of climate change, water-related ESs, such as water retention and storage on and below the surface as well as control of floods, water pollution and soil erosion, are of increasing importance. The productivity of agricultural crops is enhanced by more atmospheric CO2 but restricted by higher drought susceptibility. The value of floodplain landscapes, i.e. their agroecological, nature conservation, tourism (aesthetic) and other potentials, however, will be increasingly controlled by their water supply, which is characterized by hydrometeorological parameters. Case studies are presented for the estimation of the value of two water-related regulating ESs (water retention and groundwater recharge capacities) in the floodplains of the Kapos and Drava rivers, Southwest Hungary. -

Oryza Glaberrima

African rice (Oryza glaberrima) cultivation in the Togo Hills: ecological and socio-cultural cues in farmer seed selection and development and socio-cultural cues in farmer seed selection development African rice ( Oryza glaberrima ) cultivation in the Togo Hills: ecological Togo ) cultivation in the Béla Teeken Béla Béla Teeken African rice (Oryza glaberrima) cultivation in the Togo Hills: ecological and socio-cultural cues in farmer seed selection and development Béla Teeken Thesis committee Promotors Prof. Dr P. Richards Emeritus professor of Technology and Agrarian Development Wageningen University Prof. Dr P.C. Struik Professor of Crop Physiology Wageningen University Co-promotors Dr H. Maat Assistant Professor Knowledge, Technology and Innovation group Wageningen University Dr E. Nuijten Senior Researcher Plant Breeding & Sustainable Production Chains Louis Bolk Institute Other members Prof. Dr H.A.J. Bras, Wageningen University Prof. Dr S. Hagberg, Professor of Cultural Anthropology, Uppsala University, Sweden Dr T.J.L. van Hintum, Wageningen University Dr S. Zanen, Senior Trainer Consultant, MDF Training & Consultancy, Ede This research was conducted under the auspices of the Wageningen School of Social Sciences (WASS). African rice (Oryza glaberrima) cultivation in the Togo Hills: ecological and socio-cultural cues in farmer seed selection and development Be´la Teeken PHD Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of doctor at Wageningen University by the authority of the Rector Magnificus Prof. Dr A.P.J. Mol, in the presence of the Thesis Committee appointed by the Academic Board to be defended in public on Tuesday 1 September 2015 at 4 p.m. in the Aula. Béla Teeken African rice (Oryza glaberrima) cultivation in the Togo Hills: ecological and socio-cultural cues in farmer seed selection and development 306 pages PhD thesis, Wageningen University, Wageningen, NL (2015) With references, with summaries in English and Dutch ISBN: 978-94-6257-435-9 Abstract Teeken B (2015).