Actors in Water Governance: Barriers and Bridges for Coordination

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

50 Jahre Pro Natura Baselland 1966–2016

2/16 Baselland 50 Jahre Pro Natura Baselland 1966–2016 Baselland Geleitwort Als vor 50 Jahren der BNBL gegründet die Volksinitiative zum Schutz der Strom- wurde, hätte ich niemals geahnt, dass ich landschaft Rheinfall – Rheinau. Die Na- als Urgestein das Geleitwort zum Jubiläum tur- und Heimatschützer wurden damals schreiben würde! so empfindlich getroffen, dass sich daraus das erste Landschaftsschutzkonzept der Im Gründungsjahr 1966, drei Jahre nach Schweiz entwickelte: Das «Inventar der zu der Jahrhundert-Seegfrörni von Zürich- erhaltenden Landschaften und Naturdenk- und Bodensee, die man frierenderweise als mäler von nationaler Bedeutung» (KLN). Mitglied der noch 2000-Watt-Gesellschaft Dieses von den privaten Natur- und Hei- erlebt hatte, stand das Baselbiet im Ent- matschutzorganisationen erarbeitete KLN- wicklungsschub der Hochkonjunktur. Der Inventar lag 1963 gedruckt vor und wurde Autobahnbau schlug Schneisen der Ver- den Behörden und Politikern als Postulat wüstung von biblischer Dimension, denn der Verbände übergeben. Die KLN-Gebiete bis dahin war das Berge Versetzen dem im Baselbiet und deren Schutz beschäftig- Glauben vorbehalten. ten mich bereits ab 1966. Die Naturschutz- organisationen übernahmen seit Jahrzehn- Damals gab es im Baselbiet etwa 27’500 ten Aufgaben, die der Staat nicht erfüllte. Foto: Eduard Perret, TherwilFoto: Autos; heute sind es fast 200’000! 1960 Klaus Ewald war das jüngste Gründungsmitglied des BNBL. Er hat seinen Kampfgeist für eine lebten im Baselbiet 148’300 und 2014 etwa Was hat die Naturschützer der Schweiz intakte Natur und Umwelt nie verloren und 286’000 Personen. Dieses enorme Wachs- damals bewegt? Neben den Schutzgebie- wurde später erster – und bis anhin letzter – tum hat sich im Bild der Landschaft nieder- ten und dem Artenschutz standen Ener- Professor für Natur- und Landschaftsschutz an der ETH Zürich. -

4434 Hölstein, 22

Gemeindenachrichten Waldenburgertal Arboldswil, Bennwil, Hölstein, Lampenberg, Langenbruck, Liedertswil, Niederdorf, Oberdorf, Titterten und Waldenburg vom 25. Januar 2021 Vor-Registrierung für Impftermine ab Dienstag, 26. Januar möglich Der kantonale Krisenstab teilt mit: Zurzeit stehen nur sehr wenig Impfdosen zur Verfügung. Der Kanton Basel-Landschaft will dennoch dem Wunsch der Bevölkerung Rechnung tragen und bietet ab Dienstag, 26. Januar, eine Vor-Registrierung im Sinne einer Warteliste für Impftermine an. Diese Vor-Registrierung ist online via www.bl.ch/impfen oder telefonisch via Medgate-Infoline unter 058 387 77 07 möglich. Sobald neue Impfstoff-Lieferungen seitens Bund wieder garantiert und neue Impfter- mine vorhanden sind, werden diese dann an die eingetragenen Personen zugewiesen. Damit werden Impf- willige vom Druck entlastet, sich konstant über neue Impftermine informieren zu müssen. Zur Vor-Registrierung (Warteliste) sind aktuell Personen mit Wohnsitz im Kanton Basel-Landschaft zugelas- sen, welche eines der beiden nachfolgenden Kriterien erfüllen: - Alter über 75 Jahre (Geburtsdatum 30. Juni 1946 oder davor) - Personen mit chronischen Erkrankungen mit höchstem Risiko gemäss BAG-Definition (ärztlich un- terschriebenes Attest muss am Impftermin mitgebracht werden) Sirenentest am Mittwoch, 3. Februar Am Mittwoch, 3. Februar findet der jährliche schweizweite Sirenentest statt. Dabei wird die Funktionsbereit- schaft der rund 150 Sirenen im Kanton für den "Allgemeinen Alarm" und für den "Wasseralarm" getestet. Es sind keine Verhaltens- und Schutzmassnahmen zu ergreifen. Ausgelöst wird ab 13.30 Uhr das Zeichen “Allgemeiner Alarm“, ein regelmässig auf- und absteigender Heulton von einer Minute Dauer. Getestet wird nebst der zentralen Auslösung durch die Polizei Basel- Landschaft ab 13.45 Uhr eine zweite Alarmierung via Sirenen über eine separate Auslösestation. -

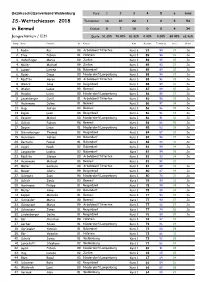

JS-Wettschiessen 2018 in Bennwil

Bezirksschützenverband Waldenburg Kurs 1 2 3 4 5 6 total JS-Wettschiessen 2018 Teilnehmer 16 10 22 1 0 5 54 in Bennwil Kränze 5 7 18 0 0 4 34 Jungschützen / U21 Quote 31.25% 70.00% 81.82% 0.00% 0.00% 80.00% 62.96% Rang Name Vorname JG Kursort Kurs Resultat Tiefschuss Serie Kranz 1. Rudin Kai 98 Arboldswil/Titterten Kurs 6 91 99 37 Ja 2. Frey Fabian 01 Hölstein Kurs 3 89 98 36 Ja 3. Häfelfinger Marco 99 Ziefen Kurs 3 89 95 35 Ja 4. Müller Michael 99 Ziefen Kurs 3 89 93 37 Ja 5. Lusser Lorenz 98 Bubendorf Kurs 6 89 85 32 Ja 6. Buser Diego 00 Niederdorf/Lampenberg Kurs 3 88 98 37 Ja 7. Räuftlin Aaron 99 Arboldswil/Titterten Kurs 3 88 96 35 Ja 8. Wehrli Silas 99 Reigoldswil Kurs 3 88 95 36 Ja 9. Wisler Lukas 99 Bennwil Kurs 3 87 89 35 Ja 10. Hajdini Lirim 00 Niederdorf/Lampenberg Kurs 3 86 99 37 Ja 11. Leuenberger Cyrill 01 Arboldswil/Titterten Kurs 3 86 98 35 Ja 12. Heinimann Celine 01 Bennwil Kurs 2 86 97 34 Ja 13. Hugi Adrian 00 Bennwil Kurs 3 86 96 35 Ja 14. Rigoni Leon 98 Reigoldswil Kurs 6 86 96 33 Ja 15. Beyeler Michel 00 Niederdorf/Lampenberg Kurs 3 86 91 36 Ja 16. Schick Fabian 98 Bennwil Kurs 6 86 86 35 Ja 17. Degen Linus 01 Niederdorf/Lampenberg Kurs 1 85 83 35 Ja 18. Dürrenberger Thomas 02 Reigoldswil Kurs 2 84 87 31 Ja 19. -

RVL Tarifzonenplan Mit TNW-Zonen 10 Und 40

nach Freiburg Notschrei nach nach Titisee Münstertal Muggen- Todtnauberg Feldberg brunn nach Freiburg Wiedener Eck 7 Fahl Belchen Branden- berg Todtnau Notschrei Multen Schlechtnau nach nach Titisee nach Münstertal Müllheim Utzenfeld Abzw.Präger Böden Todtnauberg Haldenhof 7 Geschwend Muggen- Feldberg brunn Neuenweg Präg Fachklinik nach nach nach Kandertal Freiburg Müllheim Müllheim Schönau Wiedener Eck Fahl 6 Bürchau 7 Wembach Schallsingen Marzell Belchen Branden- Mauchen 7 Hochkopfhaus Wies Raich berg Nieder- Todtnau eggenen Ehrsberg Multen Obereggenen 5 Schliengen 4 Sitzen- Schwand Schlechtnau Feuerbach kirch Liel Malsburg nach Mambach Abzw.Präger Adelsberg Müllheim Utzenfeld Hertingen Böden Bad Lehnacker Tegernau Atzenbach Haldenhof 7 Geschwend Bamlach Bellingen Riedlingen Kandern Sallneck Gresgen Zell im Gersbach Neuenweg Tannenkirch Wiesental Rheinweiler 5 6 Präg Welmlingen Schlächtenhaus Fachklinik RVL TarifzonenplanHolzen Hammerstein Wieslet nach nach nach Kandertal Enkenstein Hausen-Raitbach Freiburg Müllheim Müllheim Kleinkems Mappach Schönau Weitenau 6 6 Bürchau Wollbach Fahrnau Wembach Istein 4 Egringen Hägelberg Langenau Schallsingen Marzell Efringen- Wittlingen 7 Kirchen Mauchen Hochkopfhaus mit TNW-ZonenSchallbach 10 undSchlattholz 40 Raich 3 Hauingen Maulburg Hasel Wies Fischingen Rümmingen Nieder- Steinen Schopfheim Schopfheim Eimel- Richtung eggenen Ehrsberg West Wiechs dingen 1 Brombach/ Wehr Obereggenen 5 Binzen Hauingen Hüsingen Schliengen Märkt Tumringen Haagen/Messe 4 Sitzen- Schwand 3 Ötlingen Schwarzwaldstr. Feuerbach -

Liste Der Hilfsangebote Im Kanton Basel-Landschaft

Liste der Hilfsangebote im Kanton Basel-Landschaft Stand aktuell (Angebote in den Gemeinden) Zusammengestellt von benevol Baselland Kontakte Bezirk Kanton/Gemeinden benevol Baselland: Kompetenzzentrum für Freiwilligenarbeit Kanton Basel-Landschaft Website Kontaktperson Mail Tel. Kanton Basel-Landschaft Kantonaler Krisenstab: "Hand in Hand fürs Baselland": Freiwillige Helferinnen undhttps://coronahelfer.ch Helfer Team Kanton Basel-Landschaft Rotes Kreuz Baselland: Besorgungsdienst http://srk-baselland.ch/besorgungsdienst-srk Team [email protected] 061 905 82 00 Kanton Basel-Landschaft Evangelisch-reformierte Landeskirche Baselland www.refbl.ch Team 061 926 81 81 Kanton Basel-Landschaft Römisch-katholische Landeskirche Baselland: Fachbereich Diakonie www.kathbl.ch/corona-hilfsangebote Team 061 925 17 03 Kanton Basel-Landschaft Psychiatrie Baselland: Corona Hotline (Telefonische Hilfe und Beratung) www.pbl.ch Team 061 553 54 54 Kanton Basel-Landschaft Perspektiva plus: kostenlose Konflikthilfe in Krisensit. durch Mediatoren www.perspektiva.ch Team Kanton Basel-Landschaft Pro Senectute: Projekt " Hotline Spontan" (Einkauf, Abh. Med., Hunde) www.bb.pro-senectute.ch/spontan. Team [email protected] 061 206 44 42 Kanton Basel-Landschaft Pro Senectute/Migros: Amigos (Gratislieferung von Migros Produkten) www.amigos.ch Team 0800 789 000 Kanton Basel-Landschaft benevol Baselland: Kompetenzzentrum für Freiwilligenarbeit Kanton Basel-Landschaftwww.benevol-baselland.ch Karin Fäh [email protected] 061 921 71 91 Kanton Basel-Landschaft Digitale Plattform: five up www.fiveup.ch Team [email protected] Kanton Basel-Landschaft Digitale Plattform: Hilfe jetzt! www.hilf-jetzt.ch Team [email protected] Kanton Basel-Landschaft Facebook-Gruppe: #gärngschee (online Medium) www.bajour.ch Team [email protected] 061 271 02 02 Kanton Basel-Landschaft Winterhilfe: Fonds für Familien in Not www.bl.winterhilfe.ch Dina Marmora gesuche@[email protected] 061 781 14 81 Kanton Basel-Landschaft Gesundheitsförderung BL: Inform. -

Mitteilungsblatt Vom 21.09.2020

Gemeinde Oberdorf Nr. 198/20 E I N L A D U N G Z U R E I N W O H N E R G E M E I N D E V E R S A M M L U N G vom Montag, 21. September 2020, um 20.00 Uhr in der Mehrzweckhalle der Primarschule Oberdorf Traktanden: 1) Genehmigung Protokoll 2) Änderung Statuten Zweckverband der Musikschule beider Frenkentäler 3) Änderung Vertrag über den Schulrat der Musikschule beider Frenkentäler 4) Genehmigung Dienstbarkeitsvertrag unselbständiges Baurecht zugunsten der Jagdgesellschaft Oberdorf 5) Genehmigung Änderungen Wasserliefervertrag Auf Arten 6) Verschiedenes - Information Revision Zonenvorschriften Siedlung DER GEMEINDERAT Das Mitteilungsblatt mit den detaillierten Erläuterungen kann auf der Gemeindeverwal- tung einzeln oder als Abo bezogen werden. Ausserdem kann es auf unserer Home- page heruntergeladen werden: http://www.oberdorf.bl.ch / Politik / Gemeindeversammlung/ Sie erreichen uns unter: Tel. 061 965 90 90 oder [email protected] 2 Schutzkonzept Der Bundesrat hat aufgrund der Entwicklung der epidemiologischen Lage die Massnahmen zur Bekämpfung des neuen Coronavirus per 22.06.2020 weitgehend aufgehoben. Für alle öf- fentlich zugänglichen Einrichtungen und Betriebe sowie Veranstaltungen braucht es jedoch weiterhin ein Schutzkonzept. Die Vorgaben wurden indes vereinfacht und vereinheitlicht. Ab- stands- und Handhygieneregeln bleiben zentral und sollen helfen, Neuansteckungen und da- mit einen Wiederanstieg der Fallzahlen zu verhindern. Abstand Grundsätzlich ist der Mindestabstand zwischen zwei Personen von 1.5 Meter einzuhalten. Falls dieser nicht eingehalten werden kann, kann stattdessen das Tragen von Masken vorge- sehen werden. Händehygiene Die Händehygiene ist eine grundlegende Massnahme zur Verhinderung der Übertragung von Keimen. Allen Personen muss es möglich sein, sich regelmässig die Hände zu reinigen. -

WEP Waldenburgertal Einleitung

Rufsteinweg 4, Postfach 307 Amt für Wald beider Basel CH-4410 Liestal Telefon 061 552 56 59 Telefax 061 552 69 88 Liestal Waldentwicklungsplan Waldenburgertal 2013 – 2029 Umfassend die Gemeinden Arboldswil, Bennwil, Hölstein, Lampenberg, Liedertswil, Niederdorf, Oberdorf, Ramlinsburg und Titterten (Revier Dottlenberg, Revier BHR) Genehmigtes Exemplar (RRB Nr. 1483 vom 30. September 2014) Dazu gehören rechtsverbindliche Pläne über die Waldfunktionen, die Objekte mit besonderer Zielsetzung und zur Erschliessung und Wegbenützung. Amt für Wald beider Basel Externe Begleitung Beat Feigenwinter, Kreisforstingenieur, René Bertiller, Forstingenieur, Winterthur Projektleiter Christoph Hitz, Produkteverantwortlicher Revierförster René Lauper, Forstbetriebsverband Dottlenberg Daniel Wenk, Forstrevier Bennwil-Hölstein-Ramlinsburg WEP Waldenburgertal Einleitung Impressum: Begleitgruppe: Ständige Mitglieder Beat Feigenwinter, Projektleiter, Kreisforstingenieur, Amt für Wald beider Basel Christoph Hitz, Produktverantwortlicher, Amt für Wald beider Basel René Lauper, Revierförster, Forstbetriebsverband Dottlenberg Daniel Wenk, Revierförster, Forstrevier Bennwil-Hölstein-Ramlinsburg René Bertiller, Dipl. Forstingenieur ETH, Winterthur Temporäre Mitglieder Andrea De Micheli, Dipl. Forstingenieur ETH, Zürich Verena Kugler, Waldchefin Oberdorf Jeremias Heinimann, Waldchef Bennwil Christine Massafra, Waldchefin Ramlinsburg Bearbeitung der Grundlagen: Christoph Hitz, Produktverantwortlicher, Amt für Wald beider Basel Mitwirkende: Abegglen Beat, Verschönerungsverein -

Das Projekt 64Plus 3

Mitgliederversammlung BAP vom 18. Juni 2009 Ziel des Referates Ziel des Referates ist: Alterspolitik im Kanton Basel-Landschaft 1. Kurzer Einstieg 2. Bedeutung und Position Projekt 64plus Das Projekt 64plus 3. Einige allgemeine Rahmenbedingungen 3. IST-Situation aus div. Sichten 4. Ziele und Kernpunkte der kantonalen Altersspolitik Referat von John Diehl 5. Handlungsfelder / Massnahmen / Zuständigkeiten Projektleiter 64plus 6. Erfolgsfaktoren für die Planung und Umsetzung 7. Lösungsansätze 8. Weiteres Vorgehen / Projekt 64plus Bedeutung und Position Projekt 64plus Bedeutung und Position Projekt 64plus Bedeutung des Projektes 64 plus: Position Projekt 64plus 1. Ziel ist die Gesamt-Planung Alterspolitik Kanton 1. Weiterführung des Projektes „Zukunfts- Basel- Landschaft mit den 2 Bereichen: werkstatt Alter“ (BAP/PS/SPITEX) - Seniorenpolitik 2. Es basiert auf den Zukunftswerkstatt-Papieren - Alterspflegepolitik - Altersplanung Baselland Phase 1: Rahmenbedingungen und 2. Definition der Handlungsfelder / Massnahmen Handlungsfelder - Papieren BAP, VBLG, SPITEX und PS. 3. Definition der Zuständigkeiten / wer macht was! 3. Gesetz / Verordnung GeBPA 4. Anstoss zur gemeinsamen Zusammenarbeit 5. Anstoss zu Umsetzungen 4. Kanton BL Bericht zur Altersversorgung 1997 Bedeutung und Position Projekt 64plus Bedeutung und Position Projekt 64plus Position Projekt 64plus Zusammenfassung und Weitere Aussagen zur IST-Situation Alterspolitik Umsetzungsorganisation Kanton BL und Definition von Handlungsfelder: Projektteam 64plus - Alterskonferenz BL - Parteien FDP und SP (Leitbilder) Zukunftswerkstatt Alter: Gemeinde - Div. Motionen - SPITEX Alterskonferenz BL - Altersleitbilder (z.B. Farnsburg/Schaffmatt/Reinach/Oberwil…..) - Pro Senectute - Konzepte/Lösungen: WATAL, Leimental, ZEROSA Kanton - Altersvereine: Graue Panther/SVNW - VBLG - ……etc. - BAP Weitere.. Einige Rahmenbedingungen....hier sind wir gefordert! Einige Rahmenbedingungen....hier sind wir gefordert! Demographie… . Die Familienstrukturen verändern sich. hier sind wir Die Generationen leben getrennt. gefordert ! . -

Mitteilungsblatt Dezember 2010

MITTEILUNGSBLATT Gemeinde Bretzwil Offizielles Publikationsorgan der Gemeinde Bretzwil 25. Jahrgang Nr. 99 Erscheint vierteljährlich Dezember 2010 Auflage: 370 Exemplare Redaktionsadresse: 4207 Bretzwil, Gemeindeverwaltung Redaktionsschluss: jeweils der 10. des Monats vor Quartalsende Inserate: 1/1-Seite A4 Fr. 80.-- / ½-Seite A5 Fr. 40.-- / ¼-Seite A6 Fr. 20.-- / 1/8-Seite A7 Fr. 10.-- Öffnungszeiten der Gemeindeverwaltung: Montag, Mittwoch, Freitag 09.00 - 11.00 Uhr Donnerstag 17.00 - 19.00 Uhr Telefon 061 943 04 40 - Fax 061 943 04 41 - [email protected] Sprechstunde des Gemeindepräsidenten nach Vereinbarung. Telefonische Anfragen Montag bis Freitag von 18.30 - 19.30 Uhr, 079 422 54 13. Für dringende Angelegenheiten jederzeit. Der Gemeinderat und die GemeindeGemeindeangestelltenangestellten wünschen eine besinnliche Weihnachtszeit und einen guten Rutsch ins NNeueeue Jahr Mitteilungsblatt der Gemeinde Bretzwil Nr. 99 Seite 2 Aus den Verhandlungen des Gemeinderates I RRREVIERBEITRAG HHHOHEITSAUFGABEN 2010 Gestützt auf die §§ 51, 52, 53 und 70 Abs. 3 der Waldverordnung vom 11. Juni 1998 wird für die vom Kanton an den Revierförster übertragenen Hoheitsaufgaben eine jährliche Pauschalabgeltung vorgenommen. Die Vergütung an die Revierverbände richtet sich nach den kantonalen forststatistischen Daten bezüglich Flächen, Hiebsätzen und der Anzahl nicht betriebsplanpflichtiger Waldeigentümer sowie hinsichtlich der massgebenden Einwohnerzahl nach dem kantonalen statistischen Jahrbuch. Für das Forstjahr 2009/2010 wird dem Forstrevier -

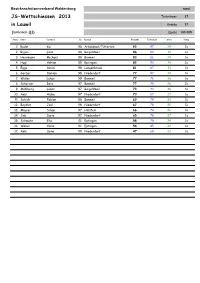

JS-Wettschiessen 2013 in Lauwil Übersicht

Bezirksschützenverband Waldenburg total JS-Wettschiessen 2013 Teilnehmer 17 in Lauwil Kränze 17 Junioren (JJ) Quote 100.00% Rang Name Vorname JG Kursort Resultat Tiefschuss Serie Kranz 1. Rudin Kai 98 Arboldswil/Titterten 93 97 39 Ja 2. Rigoni Leon 98 Reigoldswil 86 84 32 Ja 3. Heinimann Michael 98 Bennwil 83 86 34 Ja 4. Hugi Adrian 00 Eptingen 82 93 34 Ja 5. Eggs David 98 Langenbruck 81 87 33 Ja 6. Gerber Damian 98 Niederdorf 77 97 32 Ja 7. Wisler Lukas 99 Bennwil 77 76 28 Ja 8. Scherrer Reto 97 Bennwil 77 75 28 Ja 9. Mühlberg Lukas 97 Reigoldswil 73 74 28 Ja 10. Aebi Aicha 97 Niederdorf 70 87 27 Ja 11. Schick Fabian 98 Bennwil 69 79 23 Ja 12. Beyeler Joel 98 Niederdorf 67 78 22 Ja 13. Maurer Silvan 97 Hölstein 66 74 26 Ja 14. Job Dario 97 Niederdorf 65 78 27 Ja 15. Schmutz Elia 01 Eptingen 58 70 24 Ja 16. Weber Yanis 01 Eptingen 54 85 23 Ja 17. Aebi Caine 00 Niederdorf 47 69 23 Ja 18. 19. 20. 21. 22. 23. 24. 25. 26. 27. 28. 29. 30. Bezirksschützenverband Waldenburg Kurs 1234total JS-Wettschiessen 2013 Teilnehmer 752216 in Lauwil Kränze 42219 Jungschützen Quote 57.14% 40.00% 100.00% 50.00% 56.25% Rang Name Vorname JG Kursort Kurs Resultat Tiefschuss Serie Kranz 1. Wisler Stefan 96 Niederdorf Kurs 1 90 98 39 Ja 2. Zindel Alexander 95 Reigoldswil Kurs 1 89 93 36 Ja 3. Waldner Sven 93 Arboldswil/Titterten Kurs 3 89 91 36 Ja 4. -

Village Evangelical Parish Catholic Parish Aesch Aesch Cath. Aesch and Pfeffingen Allschwil Allschwil Cath. Allschwil Anwil Olti

Village Evangelical Parish Catholic Parish Aesch Aesch Cath. Aesch and Pfeffingen Allschwil Allschwil Cath. Allschwil Anwil Oltingen and Arboldswil, Bubendorf Cath. Gelterkinden Arboldswil Bubendorf, Ziefen, Arboldswil Cath. Oberdorf-Waldenburgertal Arisdorf Arisdorf Cath. Liestal Arisheim Arisheim Cath. Arisheim Arlesheim Arlesheim Cath. Arlesheim Augst Augst, Pratteln Cath. Pratteln Benken Biel-Benken Cath. Therwil Bennwil Bennwil Cath. Oberdorf-Waldenburgertal Biel Biel-Benken Cath. Therwil Binningen Binningen Cath. Binningen Birsfelden Birsfelden, Muttenz Cath. Birsfelden Blauen Laufen Cath. Blauen Böckten Sissach Cath. Sissach Bottmingen Binningen Cath. Binningen Bretzwil Bretzwil Cath. Oberdorf-Waldenburgertal Brislach Laufen Cath. Brislach Bubendorf Bubendorf Cath. Liestal Buckten Sissach Cath. Sissach Burg Laufen Cath. Burg, Röschenz Buus Buus Cath. Gelterkinden Diegten Diegten Cath. Sissach Diepflingen Sissach Cath. Sissach Dietgen Diegten Cath. Sissach Dittingen Laufen Cath. Dittingen, Blauen, Laufen Duggingen Laufen, Arlesheim Cath. Laufen, Arlesheim Eptingen Diegten Cath. Sissach Ettingen Diegten Cath. Sissach Frenkendorf Frenkendorf Cath. Frenkendorf Füllinsdorf Füllinsdorf Cath. Frenkendorf Gelterkinden Gelterkinden Gelterkinden Giebenach Arisdorf Cath. Liestal Grellingen Grellingen Cath. Laufen, Arlesheim Häfelfingen Rümlingen Cath. Sissach Hemmiken Gelterkinden and Ormalingen Cath. Gelterkinden Hersberg Arisdorf Cath. Liestal Hölstein Bennwil Cath. Oberdorf, Waldenburgertal Itingen Bennwil Cath. Sissach Känerkinden Rümlingen -

8591891-TCW-Clubheft 2017-3.Pdf

2 Vorwort der Präsidentin 4 Jahresbericht Präsidentin 2017 6 Jahresbericht Spielleitung 2017 9 Protokoll der 37. Generalversammlung 12 Einladung zur 38. Generalversammlung 17 Antrag zu Handen der 38. Generalversammlung 20 Hinweis Beendigung der Mitgliedschaft 22 Jahresprogramm 2018 23 Zur Erinnerung an Paula Schmutz 24 Spielnachmittag „trb“ 50+ 26 Clubmeisterschaften 2017- Rückblick 28 Gratulationen- Eintritte 30 Austritte 2017 32 Anmeldung Erwachsenentraining 2018 33 Anmeldung Juniorentraining 2018 34 Interclub 2018 37 Mitgliederliste 2018 38 Wichtige Adressen 42 Nächste Ausgabe: April 2018 Redaktionsschluss: 31. März 2018 3 Vorwort Liebe Clubmitglieder International war die Tennissaison 2017 von vielen Ausfällen geprägt: Stan Wawrinka, Rafael Nadal, Novak Djokovic, Timea Bacsincsky, Belinda Bencic - um nur einige der Topspiele- rinnen und Spieler zu nennen. Nicht nur in der weiten Welt sondern auch im Waldenburgertal steht die Sai- son 2017 mehr im Zeichen von Austritten als von Eintritten. Gegenüber 7 Neuein- tritten stehen 24 Austritte und 4 Kategoriewechsel. Leider mussten uns auch zwei langjährige Mitglieder verlas- sen, wir gedenken ganz herzlich Paula Schmutz und Norbert Schön, die seit Gründung des TCW respektive seit 1999 engagiert waren, und ihren Familien. Nachdem im letzten Frühjahr Ralph Fütterer überraschend seinen Rücktritt bekannt gab, hat sich Marzia Nägelin spontan erklärt, die Finanzen wieder zu übernehmen. Nun heisst es aber für sie endgültig "ADIEU". Sie demissio- niert definitiv von ihrem Amt als Kas- sierin und Vizepräsidentin. Auch Edi Fussinger stellt nach drei Jahren als Spielleiter sein Amt zur Verfü- gung. Rahel Haenle hatte im Frühjahr demissioniert, das Amt der Administration (Protokollführung, Mitgliederkontrolle) wurde seither durch die Präsidentin übernommen und ist weiterhin vakant. 4 Auch beim Platzunterhalt hat es eine Änderung gegeben, nach anderthalb Jahren hatte Giuseppe Barone genug, den Rasenmäher über die Anlage zu schieben und Unkraut zu beseitigen.