Centre for Social Science Research the Results Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Delegation for Relations with South Africa

DELEGATION FOR RELATIONS WITH SOUTH AFRICA European Parliament / South African Parliament 9th Interparliamentary Meeting Cape Town 19-25 February 2007 Report by Mr Lapo Pistelli, Chairman of the Delegation, for the Committee on Foreign Affairs, Human Rights, Common Security and Defence Policy Development Committee EPADES\D-ZA\CR\672344EN.doc PE 391.186 A. Introduction The 9th IPM in Cape Town took place only 6 months after the visit of a South African Parliamentarian Delegation, led by Mr O. K. BAPELA, House Chairperson in the National Assembly (ANC), in Strasbourg in June 2006; this renewed frequency of contacts underlines the importance given by both partners in re-dynamising parliamentary dialogue and the intensity of parliamentary exchanges. During the visit, which focused extensively on science & technology projects, energy, as well as health issues, the EP Side was represented by a 7-Strong Parliamentary Delegation, Chaired by M. Lapo PISTELLI (ALDE); the timing of the visit was crucial as it coincided with the Government’s Budget Speech at Plenary Seating of the South African Parliament in Cape Town – a major event in South African politics, second only to the State of the Union address. The Delegation, thus, attended the Budget Speech session and was greeted by Finance Minster Trevor Manuel. All in all, in their 6 days in Cape Town, Members of the European Parliament held more than 25 meetings with their counterparts, Government Ministers, EU Ambassadors, NGOs / Research Centers as well as representatives of the Civil Society. It should be mentioned that representatives (including MPs) of both branches of Zimbabwe’s MDC (Movement for Democratic Change) were also met in the margins of the official meetings – an opportunity which proved extremely valuable for European Parliamentarians in order to grasp the situation in the country, especially as South Africa’s role in defusing the crisis was widely discussed during the IPM itself. -

01A — Page 1-21 — the SA Pink Vote (13.08.2021)

August 2021 Published by the South African Institute of Race Relations (IRR) P O Box 291722, Melville, Johannesburg, 2109 South Africa Telephone: (011) 482–7221 © South African Institute of Race Relations ISSN: 2311-7591 Members of the Media are free to reprint or report information, either in whole or in part, contained in this publication on the strict understanding that the South African Institute of Race Relations is acknowledged. Otherwise no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronical, mechanical, photocopy, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. While the IRR makes all reasonable efforts to publish accurate information and bona fi de expression of opinion, it does not give any warranties as to the accuracy and completeness of the information provided. The use of such information by any party shall be entirely at such party’s own risk and the IRR accepts no liability arising out of such use. Editor-in-chief: Frans Cronje Authors: Gerbrandt van Heerden Typesetter: Martin Matsokotere Cover design by Alex Weiss TABLE OF CONTENTS THE SA PINK VOTE . .4 Introduction . 4 Purpose of the study . 5 Why is it important to monitor the Pink Vote? . 5 Th e track record of South Africa’s political parties in terms of LGBTQ rights . 7 African National Congress (ANC). 7 Democratic Alliance (DA) . 10 Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF) . 12 Opinion poll results . 14 Key Findings . 15 South African LGBTQ voters are highly likely to turn out at the ballot box . -

Coloured’ Schools in Cape Town, South Africa

Constructing Ambiguous Identities: Negotiating Race, Respect, and Social Change in ‘Coloured’ Schools in Cape Town, South Africa Daniel Patrick Hammett Ph.D. The University of Edinburgh 2007 1 Declaration This thesis has been composed by myself from the results of my own work, except where otherwise acknowledged. It has not been submitted in any previous application for a degree. i Abstract South African social relations in the second decade of democracy remain framed by race. Spatial and social lived realities, the continued importance of belonging – to feel part of a community, mean that identifying as ‘coloured’ in South Africa continues to be contested, fluid and often ambiguous. This thesis considers the changing social location of ‘coloured’ teachers through the narratives of former and current teachers and students. Education is used as a site through which to explore the wider social impacts of social and spatial engineering during and subsequent to apartheid. Two key themes are examined in the space of education, those of racial identity and of respect. These are brought together in an interwoven narrative to consider whether or not ‘coloured’ teachers in the post-apartheid period are respected and the historical trajectories leading to the contemporary situation. Two main concerns are addressed. The first considers the question of racial identification to constructions of self-identity. Working with post-colonial theory and notions of mimicry and ambivalence, the relationship between teachers and the identifier ‘coloured’ is shown to be problematic and contested. Second, and connected to teachers’ engagement with racialised identities, is the notion of respect. As with claims to identity and racial categorisation, the concept of respect is considered as mutable and dynamic and rendered with contextually subjective meanings that are often contested and ambivalent. -

Volume 2/July/August 2013

VOLUME 2/JULY/AUGUST 2013 WE CELEBRATE AND HONOUR WOMEN MILITARY VETERANS FOR THEIR CONTRIBUTION honourJULY2.indd 1 2/19/2014 7:47:22 PM Department of Military Veterans Chief Directors Ms Xolisa Morolo Ms Nandipha Ntsaluba Mr Vernon Jacobs Mr Qondi Jali Health Care and Strategic Support Skills Development Beneficiary Support Wellness Services Service and Empowerment Service Mr Vulani Ngobeni Mr Peter Mokwena Chief Director Provincial Mr Mbulelo Musi Research and Policy Offices Head of Communication Development Mr Rabelane Tshimomola Chief Financial Officer (Not Pictured) Table of Contents • Editorial p3 • Mandela Day p4 continued on page 6 VOLUME 2/JULY/AUGUST 2013 • 50th Anniversary of the Raid on Liliesleaf p5 • Umzana Women Military Veterans p7 WE CELEBRATE AND HONOUR WOMEN • DMV Housing Programme in Kraaipan p8-9 MILITARY VETERANS FOR THEIR CONTRIBUTION • Election of MVA’s Leadership p10 • Profiling Women Military Veterans p11-15 WE CELEBRATE AND HONOUR WOMEN MILITARY VETERANS FOR THEIR CONTRIBUTION honourJULY2.indd 2 2/19/2014 7:47:25 PM EDITORIAL HONOUR Military Veterans Taking Their Destiny into Their Own Hands The Department of Military Veterans led by the Director General, Mr. Tsepe Motumi and working in concert with the South African National Military Veterans Association (SANMVA) as well as other various military associa- tions is powering towards the establishment of the umbrella body for mili- tary veterans nationally.Between the 27th September and 1st October 2013 history will be made and a new chapter opened in the life of the military veterans community in SA. 600 delegates from across the military veterans spectrum will converge at the Birchwood Conference Centre in Boksburg, Ekurhuleni. -

The Occasion to Launch the EPWP National Youth Service

The Minister of Public Works, Ms Thoko Didiza, gives an address at the occasion to launch the EPWP National Youth Service Venue: Botshabelo Stadium, Bloemfontein, Free State Date: Saturday 14 April 2007 ° Deputy President, Phumzile Mlambo-Ngcuka, ° Premier of the Free State, Ms Beatrice Marshoff ° Members of the Executive Council and the Provincial Legislature ° All the Executive Mayors and Councillors present ° Representatives of our political parties, non-governmental and community based organizations ° Senior government management and leadership ° Distinguished guests ° Ladies and Gentlemen: In just 2 weeks from now, on the 27th of April 2007 our country will be celebrating its 13th birthday of democratic rule. On the 27th April, we will celebrate freedom, we will mark the progress made on our journey of transformation, and we will recommit ourselves to the ongoing task of creating a better life for the people of South Africa. Today we celebrate another milestone on that journey, as we launch the EPWP National Youth Service Programme, a programme of 1 commitment to the youth, and also a programme of commitment by the youth of our country to serve the people of South Africa. Madam Deputy President, Today’s launch also marks the commitment of Public Works at national and provincial level in response to President Thabo Meki’s call to boost the scope and impact of government’s Expanded Public Works Programme (EPWP). The EPWP Youth Service Programme is therefore a joint initiative with the Umsobomvu Youth Fund, the Department of Labour and the Provincial Departments of Public Works. Together we will increase the number of young people engaged in the National Youth Service by 20 000. -

February 2012, the President of the Republic of South to Bedevil Our Continent

“This year, we dedicate the dinner to the legacy of Liberation Movements in Africa, and the contribution of diplomacy to the attainment of our freedom as African people. We chose this theme, on the one hand, to recognise the centenary of the African National Congress (ANC) and, on the other, to join many countries on our continent who have been celebrating 50 years of their independence from colonial rule. Today, we pay tribute to the sons and daughters of this great continent who, when faced with two choices either to submit or fight, they chose to fight for the freedom, democracy and development we now enjoy. Today, we rededicate ourselves to the ideals of justice and a better life for all, in a better South Africa, Africa and the world.” Minister Maite Nkoana-Mashabane A CHRONOLOGICAL LIST OF INDEPENDENCE DATES FOR AFRICA COUNTRY INDEPENDENCE DATE PRIOR RULING COUNTRY Liberia, Republic of 26 July 1847 - the South Africa, Republic of 31 May 1910 Britain diplomat vol.2 INSIDE Egypt, Arab Republic of 28 February 1922 Britain “Celebrating the Legacy of Liberation Movements in Africa-Freedom Ethiopia 1, People’s Democratic Republic of 5 May 1941 Italy In this issue through Diplomacy” Libya (Socialist People’s Libyan Arab Jamahiriya) 24 December 1951 Britain Sudan, Democratic Republic of 1 January 1956 Britain/Egypt Editorial team Style, Fair and all things Grand at this year’s Morocco 2, Kingdom of 2 March 1956 France 2 8 the diplomat is an internal newsletter Annual Minister’s Dinner of the Department of International Tunisia, Republic -

Pressure on Model School to Shape Up

PRESSURE ON MODEL SCHOOL TO SHAPE-UP By Tselane Moiloa KROONSTAD – The Free State provincial government’s education theme during the weeklong celebrations to mark former president Nelson Mandela’s birthday on Wednesday, July 18, has resonated with learners at Bodibeng Secondary School who have been asked to change the path the school has taken in recent years. Located between the dusty townships of Marabastad and Seeisoville, Bodibeng was counted among the best schools in Free State and South Africa during the apartheid regime and the early 90s, after producing luminaries like the late Adelaide Tambo and former Minister of Communications Ivy Matsepe-Casaburri, Mosuioa “Terror” Lekota, MEC Butana Khompela and his soccer-coach brother Steve Khompela. The school, which was founded in 1928 under the name Bantu High, was the only school for black people during the apartheid regime which offered a joint matriculation board qualification instead of the Bantu education senior certificate, putting it on par with the regime’s best schools of the time. Until 1982, it was the only high school in Kroonstad. But the famed reputation took a knock, despite an abundance of resources. “There is obviously a lot of pressure on us to continue with the legacy and it only makes sense that we come through with our promise to do so,” Principal Itumeleng Bekeer said. Unlike many schools which complain about things like unsatisfactory teacher-learner ratios, Bekeer said this is not a concern because the 24 classes from grade eight to 12 have an average 1:24 teacher-learner ratio. However, the socio-economic circumstances in the surrounding townships impact negatively on learners, with a lot coming to school on empty stomachs. -

Winkie Direko-A Political Leader in Her Own Right?

JOERNAAL/JOURNAL TWALA/BARNARD WINKIE DIREKO-A POLITICAL LEADER IN HER OWN RIGHT? Chitja Twala* and Leo Barnard** 1. INTRODUCTION To record merely that Winkie Direko, present premier of the Free State Province, was born on 27 November 1929 in Bochabela (Mangaung) and to an average family, will be an inadequate prelude to assessing her community and political life, which had an impact on her political career. Her entry into full-time party politics after the April 1994 first non-racial democratic election in South Africa caused a great stir in the Free State Province, and no one ever expected that she would rise to the premiership position after June 1999. This article attempts to provide an accurate, scientific and historical assessment of Direko as a political leader in her own right amid serious criticisms levelled against her before and after her appointment as the province's premier. The article, however, does not tend to adopt a defensive stance for Direko, but rather to answer a repeatedly asked question in the political circles of the Free State Province on whether Direko is a political leader or not. The article extends beyond narrowly held views that Direko emerged to promi- nence after she had been inaugurated as the province's second woman premier in 1999. In the political arena, some critics within the ruling African National Congress (ANC) in the Free State Province claim that there is no testimonial that can more aptly describe her political leadership role. The fact that she occupied the premiership position for almost five years unlike her predecessors is testimony enough that she is a political leader in her own right. -

General Observations About the Free State Provincial Government

A Better Life for All? Fifteen Year Review of the Free State Provincial Government Prepared for the Free State Provincial Government by the Democracy and Governance Programme (D&G) of the Human Sciences Research Council. Ivor Chipkin Joseph M Kivilu Peliwe Mnguni Geoffrey Modisha Vino Naidoo Mcebisi Ndletyana Susan Sedumedi Table of Contents General Observations about the Free State Provincial Government........................................4 Methodological Approach..........................................................................................................9 Research Limitations..........................................................................................................10 Generic Methodological Observations...............................................................................10 Understanding of the Mandate...........................................................................................10 Social attitudes survey............................................................................................................12 Sampling............................................................................................................................12 Development of Questionnaire...........................................................................................12 Data collection....................................................................................................................12 Description of the realised sample.....................................................................................12 -

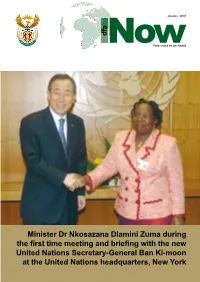

January 2007 Dfa

January 2007 dfa NowYour voice to be heard Minister Dr Nkosazana Dlamini Zuma during the fi rst time meeting and briefi ng with the new United Nations Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon at the United Nations headquarters, New York Editorial Note The dfa Now is an internal newsletter of Department of Foreign DEAR COLLEAGUES Affairs published by the Directorate: Content Development. Compliments of the New Year to you all. Editor-in-Chief: Ronnie Mamoepa elcome to the January issue of DFA Now. May 2007 bring more adventure and success to Editor: Paseka Mokhethea Wyour lives and in our efforts to build and sustain a better Africa in a better world. Editorial Committee: Genge, MP: (Acting) Chief Dir: Policy, Research & Analysis; The beginning of the month (January) South Africa Khoza, G: Dir: Operations Centre; took up its seat at the United Nations Security Council Moloto, J: Dir: Office of the Deputy Minister; (UNSC). This means that during the coming twenty-four Dikweni, NL: Dir: Economic Policy and Programming; months, as the country undertakes its mandate at the Mashabane, D: Dir Humanitarian Affairs; UNSC, there will be challenges and opportunities that Nompozolo, Mathu: Chief Dir Human Resources; will require all of us to work harder and smarter together. Shongwe, LV: Dir: Office of the DG; South Africa and the Department needs all of you to Malcomson, D: Dir NEPAD, ARF, Programme & Information rise to the occasion and make this a memorable historic Management; achievement for the country, the continent and the world Mabhongo, X: Dir : United Nations; in pursuit of world peace and stability. -

Address by Free State Premier Ace Magashule on the Occasion of the Department of the Premier’S 2014/2015 Budget Vote Speech in the Free State Legislature

ADDRESS BY FREE STATE PREMIER ACE MAGASHULE ON THE OCCASION OF THE DEPARTMENT OF THE PREMIER’S 2014/2015 BUDGET VOTE SPEECH IN THE FREE STATE LEGISLATURE 08 JULY 2014 Madam Speaker Members of the Executive Council Members of the Legislature Director General and Senior Managers Ladies and Gentlemen Madam Speaker I am delighted to present the first budget vote for the second phase of the transition taking place at the time when South Africans are celebrating 20 years of democracy. Indeed we are celebrating the remarkable gains we made in a relatively short space of time. In our celebration we cannot forget the brave and noble steps taken by heroes like our former President Nelson Rolihlahla Mandela. With July being his birthday month, we pay homage to this giant that fearlessly, fiercely and selflessly fought for South Africans to live in a democratic and open society. It is only befitting that we continue to honour him posthumously by continuing with his legacy of helping people in need and fighting injustice. In the coming days, we will go to various towns and rural areas to launch projects for the upliftment of the needy people. Our programmes will exceed the 67 minutes to enable us to leave indelible and profound memories of tangible change in their lives. In line with President Jacob Zuma’s pronouncement during the 1 State of the Nation Address, we will embark on a massive clean-up campaign in our towns, schools and other areas. Today’s budget speech marks the beginning of a period for radical economic and social transformation. -

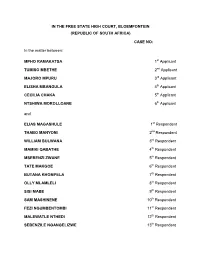

Founding Affidavit Free State High Court-20048.Pdf

IN THE FREE STATE HIGH COURT, BLOEMFONTEIN (REPUBLIC OF SOUTH AFRICA) CASE NO: In the matter between: MPHO RAMAKATSA 1st Applicant TUMISO MBETHE 2nd Applicant MAJORO MPURU 3rd Applicant ELISHA MBANGULA 4th Applicant CECILIA CHAKA 5th Applicant NTSHIWA MOROLLOANE 6th Applicant and ELIAS MAGASHULE 1st Respondent THABO MANYONI 2nd Respondent WILLIAM BULWANA 3rd Respondent MAMIKI QABATHE 4th Respondent MSEBENZI ZWANE 5th Respondent TATE MAKGOE 6th Respondent BUTANA KHOMPELA 7th Respondent OLLY MLAMLELI 8th Respondent SISI MABE 9th Respondent SAM MASHINENE 10th Respondent FEZI NGUMBENTOMBI 11th Respondent MALEWATLE NTHEDI 12th Respondent SEBENZILE NGANGELIZWE 13th Respondent 2 MANANA TLAKE 14th Respondent SISI NTOMBELA 15th Respondent MANANA SECHOARA 16th Respondent SARAH MOLELEKI 17th Respondent MADALA NTOMBELA 18th Respondent JACK MATUTLE 19th Respondent MEGGIE SOTYU 20th Respondent MATHABO LEETO 21st Respondent JONAS RAMOGOASE 22nd Respondent GERMAN RAMATHEBANE 23rd Respondent MAX MOSHODI 24th Respondent MADIRO MOGOPODI 25th Respondent AFRICAN NATIONAL CONGRESS 26th Respondent APPLICANTS’ FOUNDING AFFIDAVIT I, the undersigned, MPHO RAMAKATSA do hereby make oath and state that: 3 1. I am an adult male member of the Joyce boom (Ward 25) branch of the ANC in the Motheo region of the Free State province, residing at 28 Akkoorde Crescent, Pellissier, Bloemfontein. I am a citizen of the Republic of South Africa with ID No 6805085412084. I am also a member of the Umkhonto we Sizwe Military Veterans Association (“MKMVA”) and a former combatant who underwent military training under the auspices of the ANC in order to fight for the implementation of democracy and a bill of rights in South Africa. I have been a member of the ANC for the past 25 years.