01A — Page 1-21 — the SA Pink Vote (13.08.2021)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

& Participation

POWER & PARTICIPATION HOW LGBTIQ PEOPLE CAN SHAPE SOUTH AFRICAN POLITICS PUBLISHED BY TRIANGLE PROJECT & THE LGBTQ VICTORY INSTITUTE • FEBRUARY 2018 triangle project ISBN 978-0-620-77688-2 RESEARCHER AND AUTHOR Jennifer Thorpe CONTRIBUTORS Triangle Project Team: Matthew Clayton Elsbeth Engelbrecht LGBTQ Victory Institute team: Luis Anguita-Abolafia Caryn Viverito DESIGN & LAYOUT Carol Burmeister FIRST EDITION Printed in South Africa, February 2018 THANKS This study was made possible thanks to the support of the Astraea OPEN SOCIETY FOUNDATION Lesbian Foundation for Justice FOR SOUTH AFRICA and the Open Society Foundation of South Africa. The content of this material may be reproduced in whole or in part in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, photocopied or other means, provided the source is cited, that the use is non-commercial and does not place additional restrictions on the material. The ideas and opinions expressed in this book are the sole responsibility of the authors and those persons interviewed and do not necessarily reflect the views and opinions of Triangle Project or the LGBTQ Victory Institute. CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY i 1 INTRODUCTION TO THE STUDY 1 2 RESEARCH METHODOLOGY AND LIMITATIONS 2 2.1 METHODOLOGY 2 2.2. LIMITATIONS 2 3 LITERATURE REVIEW 4 3.1 THE SOUTH AFRICAN POLITICAL LANDSCAPE 1994 – 2017: AN OVERVIEW 4 3.2 TRANSFORMATION WITHIN THE SOUTH AFRICAN GOVERNMENT 6 3.3 LGBTIQ MILESTONES SINCE 1994 AND SA'S COMMITMENT TO HUMAN RIGHTS FOR LGBTIQ PERSONS 8 4 RESEARCH RESULTS 11 4.1 SURVEY 12 4.2 CIVIL SOCIETY INTERVIEWS 23 4.3 POLITICAL PARTIES' PERSPECTIVES ON LGBTIQ POLITICAL PARTICIPATION 34 5 BEST PRACTICE GUIDE AND RECOMMENDATIONS FOR LGBTIQ POLITICAL PARTICIPATION 43 6 DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION 48 7 REFERENCES 49 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY In early 2017, Triangle Project (Triangle) and research on political participation in South Africa, and the LGBTQ Victory Institute (Victory Institute) political party manifesto and policy analysis. -

Coloured’ Schools in Cape Town, South Africa

Constructing Ambiguous Identities: Negotiating Race, Respect, and Social Change in ‘Coloured’ Schools in Cape Town, South Africa Daniel Patrick Hammett Ph.D. The University of Edinburgh 2007 1 Declaration This thesis has been composed by myself from the results of my own work, except where otherwise acknowledged. It has not been submitted in any previous application for a degree. i Abstract South African social relations in the second decade of democracy remain framed by race. Spatial and social lived realities, the continued importance of belonging – to feel part of a community, mean that identifying as ‘coloured’ in South Africa continues to be contested, fluid and often ambiguous. This thesis considers the changing social location of ‘coloured’ teachers through the narratives of former and current teachers and students. Education is used as a site through which to explore the wider social impacts of social and spatial engineering during and subsequent to apartheid. Two key themes are examined in the space of education, those of racial identity and of respect. These are brought together in an interwoven narrative to consider whether or not ‘coloured’ teachers in the post-apartheid period are respected and the historical trajectories leading to the contemporary situation. Two main concerns are addressed. The first considers the question of racial identification to constructions of self-identity. Working with post-colonial theory and notions of mimicry and ambivalence, the relationship between teachers and the identifier ‘coloured’ is shown to be problematic and contested. Second, and connected to teachers’ engagement with racialised identities, is the notion of respect. As with claims to identity and racial categorisation, the concept of respect is considered as mutable and dynamic and rendered with contextually subjective meanings that are often contested and ambivalent. -

Opposition Party Mobilization in South Africa's Dominant

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Eroding Dominance from Below: Opposition Party Mobilization in South Africa’s Dominant Party System A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science by Safia Abukar Farole 2019 © Copyright by Safia Abukar Farole 2019 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Eroding Dominance from Below: Opposition Party Mobilization in South Africa’s Dominant Party System by Safia Abukar Farole Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science University of California, Los Angeles, 2019 Professor Kathleen Bawn, Chair In countries ruled by a single party for a long period of time, how does political opposition to the ruling party grow? In this dissertation, I study the growth in support for the Democratic Alliance (DA) party, which is the largest opposition party in South Africa. South Africa is a case of democratic dominant party rule, a party system in which fair but uncompetitive elections are held. I argue that opposition party growth in dominant party systems is explained by the strategies that opposition parties adopt in local government and the factors that shape political competition in local politics. I argue that opposition parties can use time spent in local government to expand beyond their base by delivering services effectively and outperforming the ruling party. I also argue that performance in subnational political office helps opposition parties build a reputation for good governance, which is appealing to ruling party ii. supporters who are looking for an alternative. Finally, I argue that opposition parties use candidate nominations for local elections as a means to appeal to constituents that are vital to the ruling party’s coalition. -

Political Correctness and Freedom of Expression

POLITICAL CORRECTNESS AND FREEDOM OF EXPRESSION A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of MASTERS IN POLITICS of RHODES UNIVERSITY Supervisor: Dr Antony Fluxman By: Geoffrey Embling January 2017 Abstract A brief history of political correctness is discussed along with various definitions of it, ranging from political correctness being a benign attempt to prevent offense and avert discrimination to stronger views equating it with Communist censorship or branding it as "cultural Marxism". The aim of the research is to discover what political correctness is, how it relates to freedom of expression and what wider implications and effects it has on society. The moral foundations of rights and free speech in particular are introduced in order to set a framework to determine what authority people and governments have to censor others' expression. Different philosophical views on the limits of free speech are discussed, and arguments for and against hate speech are analysed and related to political correctness. The thesis looks at political correctness on university campuses, which involves speech codes, anti discrimination legislation and changing the Western canon to a more multicultural syllabus. The recent South African university protests involving issues such as white privilege, university fees and rape are discussed and related to political correctness. The thesis examines the role of political correctness in the censorship of humour, it discusses the historical role of satire in challenging dogmatism and it looks at the psychology behind intolerance. Political correctness appeals to tolerance, which is sometimes elevated at the expense of truth. Truth and tolerance are therefore weighed up, along with their altered definitions in today's relativistic society. -

Download the Full GTC ONE Minute Brief

Equity | Currencies & Commodities | Corporate & Global Economic News | Technical Snapshot | Economic Calendar 25 June 2019 Economic and political news Key indices Former Chief Financial Officer (CFO) of the Public Investment As at 24 1 Day 1 D % WTD % MTD % Prev. month YTD % Corporation (PIC), Matshepo More, has dismissed allegations of June 2019 Chg Chg Chg Chg % Chg Chg JSE All Share impropriety and victimisation levelled against her by the PIC 58756.01 -185.46 -0.31 -0.31 5.58 -4.92 11.41 commission and PIC employees. (ZAR) Public Protector, Busisiwe Mkhwebane, has denied news reports that JSE Top 40 (ZAR) 52760.96 -141.92 -0.27 -0.27 6.40 -5.14 12.91 investigations are underway on fresh money-laundering allegations FTSE 100 (GBP) 7416.69 9.19 0.12 0.12 3.56 -3.46 10.23 against President, Cyril Ramaphosa. DAX 30 (EUR) 12274.57 -65.35 -0.53 -0.53 4.67 -5.00 16.25 Citadel Portfolio Manager, Mike van der Westhuizen, has criticised CAC 40 (EUR) 5521.71 -6.62 -0.12 -0.12 6.03 -6.78 16.72 President, Cyril Ramaphosa’s Eskom bailout plan and stated that it could S&P 500 (USD) 2945.35 -5.11 -0.17 -0.17 7.02 -6.58 17.49 pose a risk to South Africa’s fiscal debt. Nasdaq 8005.70 -26.01 -0.32 -0.32 7.41 -7.93 20.65 According to a news report, Natasha Mazzone is the front runner to Composite (USD) replace Democratic Alliance (DA) chief whip, John Steenhuisen, who is DJIA (USD) 26727.54 8.41 0.03 0.03 7.71 -6.69 14.58 MSCI Emerging set to become the party's federal executive chairperson. -

BORN out of SORROW Essays on Pietermaritzburg and the Kwazulu-Natal Midlands Under Apartheid, 1948−1994 Volume One Compiled An

BORN OUT OF SORROW Essays on Pietermaritzburg and the KwaZulu-Natal Midlands under Apartheid, 1948−1994 Volume One Compiled and edited by Christopher Merrett Occasional Publications of the Natal Society Foundation PIETERMARITZBURG 2021 Born out of Sorrow: Essays on Pietermaritzburg and the KwaZulu-Natal Midlands under Apartheid, 1948–1994. Volume One © Christopher Merrett Published in 2021 in Pietermaritzburg by the Trustees of the Natal Society Foundation under its imprint ‘Occasional Publications of the Natal Society Foundation’. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, without reference to the publishers, the Trustees of the Natal Society Foundation, Pietermaritzburg. Natal Society Foundation website: http://www.natalia.org.za/ ISBN 978-0-6398040-1-9 Proofreader: Catherine Munro Cartographer: Marise Bauer Indexer: Christopher Merrett Design and layout: Jo Marwick Body text: Times New Roman 11pt Front and footnotes: Times New Roman 9pt Front cover: M Design Printed by CPW Printers, Pietermaritzburg CONTENTS List of illustrations List of maps and figures Abbreviations Preface Part One Chapter 1 From segregation to apartheid: Pietermaritzburg’s urban geography from 1948 1 Chapter 2 A small civil war: political conflict in the Pietermaritzburg region in the 1980s and early 1990s 39 Chapter 3 Emergency of the State: detention without trial in Pietermaritzburg and the Natal Midlands, 1986–1990 77 Chapter 4 Struggle in the workplace: trade unions and liberation in Pietermaritzburg and the Natal Midlands: part one From the 1890s to the 1980s 113 Chapter 5 Struggle in the workplace: trade unions and liberation in Pietermaritzburg and the Natal Midlands: part two Sarmcol and beyond 147 Chapter 6 Theatre of repression: political trials in Pietermaritzburg in the 1970s and 1980s 177 Part Two Chapter 7 Inkosi Mhlabunzima Joseph Maphumulo by Jill E. -

EASTERN CAPE NARL 2014 (Approved by the Federal Executive)

EASTERN CAPE NARL 2014 (Approved by the Federal Executive) Rank Name 1 Andrew (Andrew Whitfield) 2 Nosimo (Nosimo Balindlela) 3 Kevin (Kevin Mileham) 4 Terri Stander 5 Annette Steyn 6 Annette (Annette Lovemore) 7 Confidential Candidate 8 Yusuf (Yusuf Cassim) 9 Malcolm (Malcolm Figg) 10 Elza (Elizabeth van Lingen) 11 Gustav (Gustav Rautenbach) 12 Ntombenhle (Rulumeni Ntombenhle) 13 Petrus (Petrus Johannes de WET) 14 Bobby Cekisani 15 Advocate Tlali ( Phoka Tlali) EASTERN CAPE PLEG 2014 (Approved by the Federal Executive) Rank Name 1 Athol (Roland Trollip) 2 Vesh (Veliswa Mvenya) 3 Bobby (Robert Stevenson) 4 Edmund (Peter Edmund Van Vuuren) 5 Vicky (Vicky Knoetze) 6 Ross (Ross Purdon) 7 Lionel (Lionel Lindoor) 8 Kobus (Jacobus Petrus Johhanes Botha) 9 Celeste (Celeste Barker) 10 Dorah (Dorah Nokonwaba Matikinca) 11 Karen (Karen Smith) 12 Dacre (Dacre Haddon) 13 John (John Cupido) 14 Goniwe (Thabisa Goniwe Mafanya) 15 Rene (Rene Oosthuizen) 16 Marshall (Marshall Von Buchenroder) 17 Renaldo (Renaldo Gouws) 18 Bev (Beverley-Anne Wood) 19 Danny (Daniel Benson) 20 Zuko (Prince-Phillip Zuko Mandile) 21 Penny (Penelope Phillipa Naidoo) FREE STATE NARL 2014 (as approved by the Federal Executive) Rank Name 1 Patricia (Semakaleng Patricia Kopane) 2 Annelie Lotriet 3 Werner (Werner Horn) 4 David (David Christie Ross) 5 Nomsa (Nomsa Innocencia Tarabella Marchesi) 6 George (George Michalakis) 7 Thobeka (Veronica Ndlebe-September) 8 Darryl (Darryl Worth) 9 Hardie (Benhardus Jacobus Viviers) 10 Sandra (Sandra Botha) 11 CJ (Christian Steyl) 12 Johan (Johannes -

African National Congress NATIONAL to NATIONAL LIST 1. ZUMA Jacob

African National Congress NATIONAL TO NATIONAL LIST 1. ZUMA Jacob Gedleyihlekisa 2. MOTLANTHE Kgalema Petrus 3. MBETE Baleka 4. MANUEL Trevor Andrew 5. MANDELA Nomzamo Winfred 6. DLAMINI-ZUMA Nkosazana 7. RADEBE Jeffery Thamsanqa 8. SISULU Lindiwe Noceba 9. NZIMANDE Bonginkosi Emmanuel 10. PANDOR Grace Naledi Mandisa 11. MBALULA Fikile April 12. NQAKULA Nosiviwe Noluthando 13. SKWEYIYA Zola Sidney Themba 14. ROUTLEDGE Nozizwe Charlotte 15. MTHETHWA Nkosinathi 16. DLAMINI Bathabile Olive 17. JORDAN Zweledinga Pallo 18. MOTSHEKGA Matsie Angelina 19. GIGABA Knowledge Malusi Nkanyezi 20. HOGAN Barbara Anne 21. SHICEKA Sicelo 22. MFEKETO Nomaindiya Cathleen 23. MAKHENKESI Makhenkesi Arnold 24. TSHABALALA- MSIMANG Mantombazana Edmie 25. RAMATHLODI Ngoako Abel 26. MABUDAFHASI Thizwilondi Rejoyce 27. GODOGWANA Enoch 28. HENDRICKS Lindiwe 29. CHARLES Nqakula 30. SHABANGU Susan 31. SEXWALE Tokyo Mosima Gabriel 32. XINGWANA Lulama Marytheresa 33. NYANDA Siphiwe 34. SONJICA Buyelwa Patience 35. NDEBELE Joel Sibusiso 36. YENGENI Lumka Elizabeth 37. CRONIN Jeremy Patrick 38. NKOANA- MASHABANE Maite Emily 39. SISULU Max Vuyisile 40. VAN DER MERWE Susan Comber 41. HOLOMISA Sango Patekile 42. PETERS Elizabeth Dipuo 43. MOTSHEKGA Mathole Serofo 44. ZULU Lindiwe Daphne 45. CHABANE Ohm Collins 46. SIBIYA Noluthando Agatha 47. HANEKOM Derek Andre` 48. BOGOPANE-ZULU Hendrietta Ipeleng 49. MPAHLWA Mandisi Bongani Mabuto 50. TOBIAS Thandi Vivian 51. MOTSOALEDI Pakishe Aaron 52. MOLEWA Bomo Edana Edith 53. PHAAHLA Matume Joseph 54. PULE Dina Deliwe 55. MDLADLANA Membathisi Mphumzi Shepherd 56. DLULANE Beauty Nomvuzo 57. MANAMELA Kgwaridi Buti 58. MOLOI-MOROPA Joyce Clementine 59. EBRAHIM Ebrahim Ismail 60. MAHLANGU-NKABINDE Gwendoline Lindiwe 61. NJIKELANA Sisa James 62. HAJAIJ Fatima 63. -

![Onderwerp: [SA-Gen] Bundel Nommer 1470](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0694/onderwerp-sa-gen-bundel-nommer-1470-750694.webp)

Onderwerp: [SA-Gen] Bundel Nommer 1470

Onderwerp: [SA-Gen] Bundel Nommer 3128 Datum: Sat Mar 1, 2008 Daar is 9 boodskappe in hierdie uitgawe Onderwerpe in hierdie bundel: 1. [KOERANT]Die Burger-RABINOWITZ Philip From: Elizabeth Teir 2a. Re: BRINK /DU TOIT From: Johan Brink 3. Upington Cemetery From: [email protected] 4a. Jordaan From: Annemie Lourens 5. N G GEMEENTE KAAPSTAD - GROOTE KERK From: Johan van Breda 6. [Koerant] The Mercury Woensdag 27 Feb 2008. From: aletta magrieta.quebbemann 7. [Koerant] The Mercury Dinsdag 26 Feb 2008 From: aletta magrieta.quebbemann 8. [Koerant] The Mercury Donderdag 28 Feb 2008. From: aletta magrieta.quebbemann 9. [Koerant] The Mercury Vrydag 29 Feb 2008 From: aletta magrieta.quebbemann Boodskap 1. [KOERANT]Die Burger-RABINOWITZ Philip Posted by: "Elizabeth Teir" [email protected] kerrieborrie Sat Mar 1, 2008 1:41 am (PST) Vinnigste 100-jarige sterf AMY JOHNSON 29/02/2008 09:15:06 PM - (SA) KAAPSTAD. – Die son het gister gesak op wat sommige die “langste wedloop ooit” genoem het. Mnr. Philip Rabinowitz, of Vinnige Phil soos hy in atletiekkringe bekend is, is gisteroggend omstreeks 05:55 in die ouderdom van 104 in sy huis in Houtbaai oorlede. Na verneem word, het Rabinowitz Dinsdag ’n beroerte gehad en kon hy sedertdien nie praat nie. Sy begrafnisdiens is gistermiddag volgens die Joodse tradisie in Pinelands gehou. Die diens is deur rabbi Desmond Maizels gelei. ’n Bewoë mnr. Hannes Wahl, Rabinowitz se afrigter van die afgelope 25 jaar, het gesê hy was die vriendelikste mens wat hy ooit geken het. “Ek gaan hom baie, baie mis. Hy laat ’n groot leemte in ons lewens.” Wahl het gesê hulle sou nog vanjaar aan ’n nommer by die Olimpiese Spele in Beijing deelgeneem het. -

Woman Held for Filming Maid's Fall from Window

SUBSCRIPTION SATURDAY, APRIL 1, 2017 RAJAB 4, 1438 AH No: 17185 Woman held for filming maid’s fall from window Min 20º 150 Fils Employer had hired runaway maid from illegal office Max 31º By Hanan Al-Saadoun and Agencies the incident itself is not a crime, but he said the Ajmi returns to Kuwait employer could be charged with negligence and KUWAIT: Police have detained a woman for film- failure to offer help. Investigations are currently KUWAIT: Saad Al-Ajmi, former ing her Ethiopian maid falling from the seventh ongoing to determine whether the case is a suicide spokesman of the opposition Popular floor in an apparent suicide attempt without try- attempt, an accident that happened while the maid Action Movement, returned home to ing to rescue her, media and a rights group said was working, or a case of attempted homicide and Kuwait late on Thursday. Ajmi, who yesterday. The Kuwaiti woman filmed her maid libel. “The law says that any person who fails to help was deported to Saudi Arabia after land on a metal awning and survive, then posted someone else who poses a grave danger to himself his citizenship was revoked, returned the incident on social media. The criminal inves- or his possessions will be punished with a maximum through the Nuwaiseeb border outlet tigation police referred the employer to the pros- three months in jail and/or a fine,” Ruwaih said. after two years in exile. An elated ecution over failing to help the victim. The The 12-second video shows the maid hanging Ajmi thanked HH the Amir Sheikh Saad Al-Ajmi hugs his children upon Kuwait Society for Human Rights yesterday outside the building, with one hand tightly gripping Sabah Al-Ahmad Al-Jaber Al-Sabah, his return home late on Thursday. -

The Rock, 2008 Fall (Vol. 79, No. 1)

Whittier College Poet Commons The Rock Archives and Special Collections Fall 2008 The Rock, 2008 Fall (vol. 79, no. 1) Whittier College Follow this and additional works at: https://poetcommons.whittier.edu/rock PURPLE GOLD GO GREEN WHITTIER COLLEGE MAGAZINE CINEMA MEETS ACADEMIA: PROFS ON FILM FALL 2008 Reconnect, Reminisce, Reunion. If it's been a short time since your Whittier College graduation, or if it's been a long time but feels like just yesterday, then it's time to come home to the Poet campus. Whittier Weekend 2008 will take place October 17-19. This year's planned events include Friday, October 17 - the Purple & Gold Athletic Hall of Fame Induction, Poet Sunday, October 19, 2008 College classes with Joe Price, Rich Cheatham '68, Greg Woirol and Charles Lame, the Clift Bookstore Dedication, a special discussion "Election 2008: Whittier Perspectives on the Political Process," Reunion Class luncheons, a Class of 1993 Frisbee Throw, the Homecoming Pep Rally, and the Grand Opening Celebration of the new Campus Center. AND THAT'S JUST THE FIRST 24 HOURS. Please join us for this very special weekend and remember just how much fun it was to be a part of not just any college, but Whittier College. .A FUL.I. SCHEDULE OF EVI. LOCr:ED ON 47 TO REGISTER FOR THIS EVENT, or for any questions about Whittier Weekend 2008, please Homecoming Reunion contact the Office of Alumni Relations, 562.907.4222 or [email protected]. whittier.edu/alumni 00 liii WHITTIER. COLLEGE Fall 2008 Volume 79, Number 1 FEATURES Purple & Gold Go Green 26 The national trend is made manifest on the Whittier College campus, driven by student interest and administrative commitment, and played out in practical, curricular, and sometimes surprising ways. -

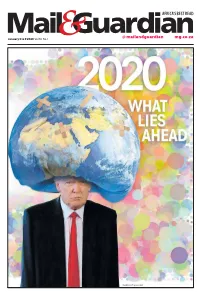

Africa's Best Read

AFRICA’S BEST READ January 3 to 9 2020 Vol 36 No 1 @ mailandguardian mg.co.za Illustration: Francois Smit 2 Mail & Guardian January 3 to 9 2020 Act or witness IN BRIEF – THE NEWS YOU MIGHT HAVE MISSED Time called on Zulu king’s trust civilisation’s fall The end appears to be nigh for the Ingonyama Trust, which controls more than three million A decade ago, it seemed that the climate hectares of land in KwaZulu-Natal on behalf crisis was something to be talked about of King Goodwill Zwelithini, after the govern- in the future tense: a problem for the next ment announced it will accept the recommen- generation. dations of the presidential high-level panel on The science was settled on what was land reform to review the trust’s operations or causing the world to heat — human emis- repeal the legislation. sions of greenhouse gases. That impact Minister of Agriculture, Land Reform and had also been largely sketched out. More Rural Development Thoko Didiza announced heat, less predictable rain and a collapse the decision to accept the recommendations in the ecosystems that support life and and deal with barriers to land ownership human activities such as agriculture. on land controlled by amakhosi as part of a But politicians had failed to join the dots package of reforms concerned with rural land and take action. In 2009, international cli- tenure. mate negotiations in Copenhagen failed. She said rural land tenure was an “immedi- Other events regarded as more important ate” challenge which “must be addressed.” were happening.