Music and Sound Design for the Screen Conference Abstracts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In the Great Tradition of Postponed NASA Launches, the York Maze

THUNDERBIRDS ARE GROW! A Thunderbirds fan has created an amazing tribute to 50 years of the iconic show by producing the World’s biggest ever Thunderbird 2, carved into an 15 acre field of growing maize plants near York, England. Tom Pearcy came up with the idea after hearing about the 50th anniversary. Says Tom Pearcy, “As a kid I remember watching Gerry Anderson’s great TV shows like Stingray & Captain Scarlet, but Thunderbirds was my favourite. I wanted to do something big to mark the 50th anniversary. As a child Thunderbird 2 captured my imagination, I think it’s the most iconic of all the Thunderbirds and being green it works perfectly carved into the field of maize plants!” Measuring over 350m (1150ft) long, Thunderbird 2 has been painstakingly carved out of over 1 million living maize plants. It took Mr Pearcy and his team of helpers nearly a week to cut out the 6km of pathways in his 15 acre field near York to form the giant Thunderbird image together with the words ‘Thunderbirds Are 50’. The pathways in the field form an intricate maze for visitors to explore. The York Maze is believed to be the largest maze in Europe and one of the largest in the world. Jamie Anderson, son of Thunderbirds creator the late Gerry Anderson, was so impressed when he heard about Mr Pearcy’s amazing maze that he had to come to York to see it for himself. Jamie took a helicopter flight over the giant 15 acre maize maze to see the design. -

Barry Gray Thunderbirds Are Go / Thunderbird 6 (Original Motion Picture Scores) Mp3, Flac, Wma

Barry Gray Thunderbirds Are Go / Thunderbird 6 (Original Motion Picture Scores) mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Stage & Screen Album: Thunderbirds Are Go / Thunderbird 6 (Original Motion Picture Scores) Country: US Released: 2014 Style: Score MP3 version RAR size: 1138 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1948 mb WMA version RAR size: 1130 mb Rating: 4.9 Votes: 919 Other Formats: VOC AU AAC MOD XM DMF ASF Tracklist 1 Main Titles And Zero X 2 Zero X Theme / Spy On Board 3 Thunderbirds Are Go / Penelope On The Move 4 Journey To Mars And The Swinging Star 5 Fall To Earth / Martian Exploration 6 Rock Snakes / Escape From Mars 7 Time Passes 8 End Titles 9 Plans To Build A Skyship And Thunderbird 6 Main Titles 10 Flight Of The Tiger Moth 11 Operation Escort 12 The Ballroom Jazz 13 Welcome Aboard / Dumping Bodies 14 Skyship Journey–Grand Canyon To Melbourne 15 Indian Street Music 16 Dinner Aboard Skyship One 17 Skyship Journey–Egypt To Switzerland And The Whistle Stop Inn 18 Thunderbirds Are Go / The Trap / Tower Collision 19 Tiger Moth Escape 20 Crash Landing And Conclusion Barcode and Other Identifiers Barcode: 826924130629 Related Music albums to Thunderbirds Are Go / Thunderbird 6 (Original Motion Picture Scores) by Barry Gray Journey - Escape Philip Glass - Roving Mars (Original Motion Picture Soundtrack) Barry Gray - Gerry Anderson's Thunderbirds Are Go The Fabulous Thunderbirds - Portfolio Hans Zimmer - Thelma & Louise / Regarding Henry (The Original Motion Picture Scores) Barry Gray / David Graham - Thunderbird 1 / Ricochet / Captain Scarlet vs. Captain Black - From Gerry Anderson's Thunderbirds (Set 5) Les Baxter & His Orchestra - Les Baxter: At The Movies (Original Film Scores) Infekt - Journey To Mars EP Zombies Of The Stratosphere - Thunderbirds Are Go John Scott - Walking Thunder (Original Motion Picture Score). -

We Can Each Make a Difference in 2020

We Can Each Make a Difference in 2020 Kluwer Mediation Blog December 28, 2019 John Sturrock (Core Solutions Group) Please refer to this post as:John Sturrock, ‘We Can Each Make a Difference in 2020’, Kluwer Mediation Blog, December 28 2019, http://mediationblog.kluwerarbitration.com/2019/12/28/we-can-each-make-a-difference-in-2020/ One of the most enjoyable aspects of the festive season is receiving and reading books that one might not have come across otherwise. This year, I have been enjoying two quite contrasting works of literature. The first is a Manual for Spectrum Agents (Haynes Publishing) providing “detailed information about the Spectrum organisation”, based on the classic 1960’s Supermarionation television series, Captain Scarlet and the Mysterons. For those of us who grew up with Captain Scarlet (and its predecessor, Thunderbirds), produced by the visionary Gerry and Sylvia Anderson, it is hard to understate to remarkable effect these TV programmes, set 100 years into the future, had on our generation. The book brings it all back. It is a serious exercise in nostalgia. The book reminds us that the basic premise of the TV series was that, by 2068, peace and prosperity had been achieved for the majority of the world’s inhabitants, under the guidance and control of a World Government. A Treaty of Tranquility had been signed in 2046, banning acts of war and aggression between countries and binding them together to fight for one cause – the defence of the Earth. The Republic of Britain was an early dissenter, though it had signed by 2050 following the overthrow of its military dictatorship in 2047. -

Television for Children: Problems of National Specificity and Globalisation

Television for children: problems of national specificity and globalisation Book or Report Section Accepted Version Bignell, J. (2011) Television for children: problems of national specificity and globalisation. In: Lesnik-Oberstein, K. (ed.) Children in Culture, Revisited: Further Approaches to Childhood. Palgrave Macmillan, Basingstoke, pp. 167-185. ISBN 9780230275546 Available at http://centaur.reading.ac.uk/21378/ It is advisable to refer to the publisher’s version if you intend to cite from the work. See Guidance on citing . Publisher: Palgrave Macmillan All outputs in CentAUR are protected by Intellectual Property Rights law, including copyright law. Copyright and IPR is retained by the creators or other copyright holders. Terms and conditions for use of this material are defined in the End User Agreement . www.reading.ac.uk/centaur CentAUR Central Archive at the University of Reading Reading’s research outputs online NOTE: This is a chapter published as Bignell, J., ‘Television for children: problems of national specificity and globalisation’ in K. Lesnik-Oberstein (ed.), Children in Culture, Revisited: Further Approaches to Childhood (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan 2011), pp. 167-185. The whole book is available to buy from Palgrave at http://www.palgrave.com/gb/book/9780230275546. My published work is listed and more PDFs can be downloaded at http://www.reading.ac.uk/ftt/about/staff/j-bignell.aspx. Jonathan Bignell Television for children: problems of national specificity and globalisation In the developed nations of Europe, and in the USA, it has long been assumed that television should address children. Thus, notions of what ‘children’ are have been constructed, and children are routinely discussed as an audience category and as a market for programmes. -

Starlog Magazine Issue

'ne Interview Mel 1 THE SCIENCE FICTION UNIVERSE Brooks UGUST INNERSPACE #121 Joe Dante's fantastic voyage with Steven Spielberg 08 John Lithgow Peter Weller '71896H9112 1 ALIENS -v> The Motion Picture GROUP, ! CANNON INC.*sra ,GOLAN-GLOBUS..K?mEDWARO R. PRESSMAN FILM CORPORATION .GARY G0D0ARO™ DOLPH LUNOGREN • PRANK fANGELLA MASTERS OF THE UNIVERSE the MOTION ORE ™»COURTENEY COX • JAMES TOIKAN • CHRISTINA PICKLES,* MEG FOSTERS V "SBILL CONTIgS JULIE WEISS Z ANNE V. COATES, ACE. SK RICHARD EDLUND7K WILLIAM STOUT SMNIA BAER B EDWARD R PRESSMAN»™,„ ELLIOT SCHICK -S DAVID ODEll^MENAHEM GOUNJfOMM GLOBUS^TGARY GOODARD *B«xw*H<*-*mm i;-* poiBYsriniol CANNON HJ I COMING TO EARTH THIS AUGUST AUGUST 1987 NUMBER 121 THE SCIENCE FICTION UNIVERSE Christopher Reeve—Page 37 beJohn Uthgow—Page 16 Galaxy Rangers—Page 65 MEL BROOKS SPACEBALLS: THE DIRECTOR The master of genre spoofs cant even give the "Star wars" saga an even break Karen Allen—Page 23 Peter weller—Page 45 14 DAVID CERROLD'S GENERATIONS A view from the bridge at those 37 CHRISTOPHER REEVE who serve behind "Star Trek: The THE MAN INSIDE Next Generation" "SUPERMAN IV" 16 ACTING! GENIUS! in this fourth film flight, the Man JOHN LITHGOW! of Steel regains his humanity Planet 10's favorite loony is 45 PETER WELLER just wild about "Harry & the CODENAME: ROBOCOP Hendersons" The "Buckaroo Banzai" star strikes 20 OF SHARKS & "STAR TREK" back as a cyborg centurion in search of heart "Corbomite Maneuver" & a "Colossus" director Joseph 50 TRIBUTE Sargent puts the bite on Remembering Ray Bolger, "Jaws: -

Download the Digital Booklet

ORIGINAL TELEVISION SOUNDTRACK A GERRY ANDERSON PRODUCTION MUSIC BY BARRY GRAY Calling International Rescue... Palm Treesflutterandthesoundofdistantcrashingwaves echoaroundaluxuriouslookinghouse.Suddenlyalow gravellyhumemergesfromaswimmingpoolasitslides aside,revealingancavernoushangerbelow.Muffled automatedsoundsecho,beforeanalmightyroarfollowedby thelightning-fastblurofarocketasitshootsskyward.Thisis Thunderbird1,high-speedreconnaissance craft,pilotedbyScottTracy. Momentsago,Scott’sbrotherJohn radioed-inadistresscallfromThunderbird5, amannedorbitalsatellite.Alifeis indangerwithallhopelost,except foronepossibility:International Rescue.JeffTracy,theboys’father assessesthesituationandduly deployshissonsintoaction. AsThunderbird1propelsitself towardsthedangerzone(now inhorizontalflight),itsfellowcraft Thunderbird2isreadiedforlaunch.This giantgreentransporterstandsontop ofaconveyer-beltofsixPods,each containingadifferentarrayoffantastic rescueequipment.WiththenecessaryPod selected,VirgilTracy(joinedbybrothers AlanandGordon)taxisthehugevehicleto thelaunchramp,whichraisesthecraftto40 degreesbeforeittooblastsskywards.International Rescueareontheirway,Thunderbirdsarego! Inspiredbythisdramaticevent,forhisnexttelevisionseriesGerry Approaching Danger Zone... Andersonenvisionedanorganisationpreparedforsucheventualities IntheAutumnof1963,writerandproducer -

Thunderbirds ™ and © ITC Entertainment Group Limited 1964, 1999 and 2017

THE COMIC COLLECTION A GERRY ANDERSON PRODUCTION TM CREATED ESPECIALLY FOR ROBIN Happy Christmas Bro. Hope this brings back some memories! Thunderbirds ™ and © ITC Entertainment Group Limited 1964, 1999 and 2017. Licensed by ITV Ventures Limited. All rights reserved. This edition is produced under license by Signature Gifts Ltd, Signature House, 23 Vaughan Road, Harpenden, AL5 4EL. Printed and bound in the UK. GDTEST0123456789 THE COMIC COLLECTION A GERRY ANDERSON PRODUCTION TM CMYK: Black=10c10m10y100k, Yellow=100y or Pantone: Pantone Black, PantoneYellow Use outline logo on dark backgronds CONTENTS THUNDERBIRD 2 TECHNICAL DATA . P68 Artist: Graham Bleathman INTRODUCTION . P4 THE SPACE CANNON . P70 Artist: Frank Bellamy THE EARTHQUAKE MAKER . P6 THE OLYMPIC PLOT . P76 Artist: Frank Bellamy Artist: Frank Bellamy VISITOR FROM SPACE . P18 DEVIL’S CRAG . P88 Artist: Frank Bellamy Artist: Frank Bellamy THE ANTARCTIC MENACE . P34 THE EIFFEL TOWER DEMOLITION . P96 Artist: Frank Bellamy Artist: Frank Bellamy BRAINS IS DEAD . P48 SPECIFICATIONS OF THUNDERBIRD 3 . P104 Artist: Frank Bellamy Artist: Graham Bleathman THUNDERBIRD 1 TECHNICAL DATA . P64 LAUNCH SEQUENCE: THUNDERBIRD 3 . P106 Artist: Graham Bleathman Artist: Graham Bleathman LAUNCH SEQUENCE: THUNDERBIRD 1 . P66 LAUNCH SEQUENCE: THUNDERBIRD 4 . P107 Artist: Graham Bleathman Artist: Graham Bleathman LAUNCH SEQUENCE: THUNDERBIRD 2 . P67 SPECIFICATIONS OF THUNDERBIRD 4 . P108 Artist: Graham Bleathman Artist: Graham Bleathman THE NUCLEAR THREAT . P110 CHAIN REACTION . P186 Artist: Frank Bellamy Artist: Frank Bellamy HAWAIIAN LOBSTER MENACE . .P120 THE BIG BANG . P202 Artist: Frank Bellamy Artist: John Cooper THE TIME MACHINE . P132 THE MINI MOON . P210 Artist: Frank Bellamy Artist: John Cooper THE ZOO SHIP . P144 THE SECRETS OF FAB 1 . -

Thunderbirds 50Th Anniversary Manual Ebook, Epub

THUNDERBIRDS 50TH ANNIVERSARY MANUAL PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Sam Denham,Graham Bleathman,Jeff Tracy | 153 pages | 15 Sep 2015 | HAYNES PUBLISHING GROUP | 9780857338235 | English | Somerset, United Kingdom Thunderbirds 50th Anniversary Manual PDF Book Very informative and a great idea. Had all the details and features that my husband liked about the show. Other memorabilia is planned for later, although release dates and retail prices have not been announced. Here in the order they appear in the opening credits , is Thunderbird 5, for example…. Additional Product Features Dewey Edition. The "off" amount and percentage simply signifies the calculated difference between the seller-provided price for the item elsewhere and the seller's price on eBay. Visit www. Great buy! Trade Paperbacks Books. Sentinel , and the Martian Space Probe as well as its transporter. Categories :. UK release of the classic box set in same format as previous editions. What does this price mean? Universal Conquest Wiki. Below is a list of products that have been released so far or are about to hit the market. Sign In Don't have an account? Bill o'Reilly's Killing Ser. This is an ongoing set, and six have been known to be released. About this product Product Information This new edition of the Haynes Thunderbirds Manual, published to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the first airing of the original Supermarionation series in September Ratings and Reviews Write a review. Verified purchase: Yes Condition: New. This wiki. I particularly like the illustrations and the detail work. And some of the guest vehicles from the series have also been given their moment in the spotlight, such as the Fireflash:. -

October 2017

Overseas Serials Phone: 045-228-3654 OctOber 2017 Programs are suspended for equipment maintenance late at night on the 5th from 1:00 to 7:00. Programs are subject to change without notice. Mon (2, 9, 16, 23, 30) Tue (3, 10, 17, 24, 31) Wed (4, 11, 18, 25) Thu (5, 12, 19, 26) Fri (6, 13, 20, 27) Sat (7, 14, 21, 28) Sun (1, 8, 15, 22, 29) 06:00 Mon. -Sun. ~24th: Star Trek: The Next Generation S1 (#4-26); ex. 5th: off-the-air; 25th~Star Trek: The Next Generation S2 (#1-7) 07:00 Mon. -Fri. ~3rd: Law & Order: Criminal Intent S5 (#19-22), 2 eps. /day; 4~18th: Law & Order: Criminal Intent S6 (#1-22), 2 eps. /day; 7th: Terrahawks S1 (#1), Star Trek: The Next 08:00 19th~Law & Order: Criminal Intent S7 (#1-18), 2 eps. /day 7: 30~[B&W]Supercar S1 (#1), Generation S1 (#1-10), 8: 00~ The Big Bang Theory S9 2 eps. /week (#2-3), 2 eps. /week; 14th~ The Big Bang Theory S9 (#3-4, 4-5, 5-6), 2 eps. /week; 8: 00~Law & Order: UK S5[J] (#1-3) 09:00 Info [J] Info [J] Info [J] Info [J] Info [J] Info [J] Info [J] 09:30 Scorpion S3 (#10-14) MacGyver (#16-20) The Player (#2-5) Falling Skies S4 (#7-10) MacGyver (#17-20) The Player (#2-5) Elementary S3 (#18-22) 10:00 10:30 ~16th: Grimm S5 (#20-22); 3rd: The Player (#2); Falling Skies S4 (#7-10) Scorpion S3 (#11-14) The Big Bang Theory S9 Falling Skies S4 (#7-10) ~15th: Grimm S5 (#20-22); 11:00 23rd~Eyewitness (#1-2) 10th~Law & Order: UK S5 (#1-4) (#1-2, 2-3, 3-4, 4-5), 2 eps. -

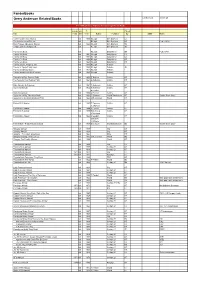

Fanderbooks Gerry Anderson Related Books List Revised: 27-Oct-08

FanderBooks Gerry Anderson Related Books List Revised: 27-Oct-08 Pre-1990 UK Gerry Anderson Annuals/Large Format Books Annual p/b © Check Title Year† h/b Year Author Publisher By ISBN ** Notes Twizzle's Adventure Stories h/b 1958 R.Leigh Birn Brothers AT The Adventures of Twizzle h/b R.Leigh Birn Brothers AT Publ. 1959? More Twizzle Adventure Stories h/b 1960 R.Leigh Birn Brothers TN Twizzle and the Hungry Cat p/b R.leigh Birn Brothers JB Torchy Gift Book h/b R.Leigh Daily Mirror SB Publ. 1960 Torchy Gift Book h/b 1961 R.Leigh Daily Mirror AT Torchy Gift Book h/b 1962 R.Leigh Daily Mirror AT Torchy Gift Book h/b 1963 R.Leigh Daily Mirror AT Torchy Gift Book h/b 1964 R.Leigh Daily Mirror AT Torchy and the Magic Beam h/b 1960 R.Leigh Pelham - Torchy in Topsy-Turvy Land h/b 1960 R.Leigh Pelham JB Torchy and Bossy Boots h/b 1961 R.Leigh Pelham - Torchy and his Two Best Friends h/b 1962 R.Leigh Pelham - Television's Four Feather Falls h/b 1960 S.Thamm Collins AT Tex Tucker's Four Feather Falls h/b 1961 S.Anderson Collins AT Mike Mercury in Supercar h/b 1961 S.Anderson Collins AT Supercar Annual h/b 1962 S.Anderson Collins AT & E.Eden Supercar Annual h/b 1963 A.Fennell Collins AT Supercar - A Big Television Book h/b 1962 G.Sherman World Distributors AT Golden Book Story Supercar on the Black Diamond Trail h/b 1965 J.W.Jennison World AT Fireball XL5 Annual h/b 1963 D.Spooner Collins AT & J.Hynam Fireball XL5 Annual h/b 1964 A.Fennell Collins AT Fireball XL5 Annual h/b 1965 D.Motton & Collins AT J.Dennison Fireball XL5 Annual h/b 1966 S.Goodall, -

EDOA 2016 09 Do

EDOA Newsletter September 2016 Do you YouTube, too? In each edition’s opening paragraph it states “…this newsletter is only as good as what you put into it,” and not having made any contribution for several years I thought it about time to do so. Being an avid reader of Organists’ Review I thought about doing something similar to Joe Riley’s piece where he not only talks about organ news, but lists five YouTube items he thinks will be of interest to the rest of us. So why not do something similar for the EDOA newsletter, thought I? There’s so much out there of interest to me that I could list, such as Widor’s 6th Symphonie for organ and orchestra, BWV 538 played by Richter (one of his last recordings) or music by the magnificent Eric Coates, including his beautifully crafted songs. I also like my jazz, rock ‘n’ roll, boogie woogie… There are fun pieces by Leroy Anderson (The Typewriter, Sandpaper Ballet, and so on), and wonderful jazz arrangements by The Swingle Singers. But for now, here are five pieces that I hope you enjoy. If you’ve got the e-newsletter then you can click directly on the link, otherwise type in the tags that I’ve given and hopefully the associated piece will be at the top of the list. 1. During our visit to St Andrew’s, Enfield on 16 July we heard movements from Samuel Wesley’s organ duet of 1812 (see Susan’s write-up elsewhere in this newsletter). It’s a lovely piece and deserves to be better known. -

Beam Aboard the Star Trektm Set Tour!

Let’s roll, Kato! Spring 2019 No. 4 $8.95 The Green Hornet in Hollywood Thunderbirds Are GO! Creature Creator RAY HARRYHAUSEN SAM J. JONES Brings The Spirit to Life Saturday Morning’s 8 4 5 TM 3 0 0 8 5 Beam Aboard the Star Trek Set Tour! 6 2 Martin Pasko • Andy Mangels • Scott Saavedra • and the Oddball World of Scott Shaw! 8 1 Shazam! TM & © DC Comics, a division of Warner Bros. Green Hornet © The Green Hornet, Inc. Thunderbirds © ITV Studios. The Spirit © Will Eisner Studios, Inc. All Rights Reserved. The crazy cool culture we grew up with Columns and Special Departments Features 3 2 CONTENTS Martin Pasko’s Retrotorial Issue #4 | Spring 2019 Pesky Perspective The Green Hornet in 11 3 Hollywood RetroFad 49 King Tut 12 Retro Interview 29 Jan and Dean’s Dean Torrence Retro Collectibles Shazam! Seventies 15 Merchandise Andy Mangels’ Retro Saturday Mornings 36 Shazam! Too Much TV Quiz 15 38 65 Retro Interview Retro Travel 41 The Spirit’s Sam Jones Star Trek Set Tour – Ticonderoga, New York 41 Retro Television 71 Thunderbirds Are Still Go! Super Collector The Road to Harveyana, by 49 Jonathan Sternfeld Ernest Farino’s Retro Fantasmagoria 78 Ray Harryhausen: The Man RetroFanmail Behind the Monsters 38 80 59 59 ReJECTED The Oddball World of RetroFan fantasy cover by Scott Shaw! Scott Saavedra Pacific Ocean Park RetroFan™ #4, Spring 2019. Published quarterly by TwoMorrows Publishing, 10407 Bedfordtown Drive, Raleigh, NC 27614. Michael Eury, Editor-in-Chief. John Morrow, Publisher. Editorial Office: RetroFan, c/o Michael Eury, Editor-in-Chief, 112 Fairmount Way, New Bern, NC 28562.