Thunderbirds Are Go Re-Booting Female Characters in Action Adventure Animation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

'Fab' Tribute to Puppet Genius Gerry Anderson

P News Release RS 6 December 2010 ROYAL MAIL PAYS ‘FAB’ TRIBUTE TO PUPPET GENIUS GERRY ANDERSON AND THUNDERBIRDS ARE GO, ON ‘MOVING’ MINI SHEET The puppet characters in Stingray, Joe 90, Captain Scarlett and Thunderbirds have enthralled millions since they first arrived on our TV screens in the 1960s, and they are now set to visit our homes again as Royal Mail pays tribute to their creator in a new set of special stamps. Issued on 11 January, FAB: The Genius of Gerry Anderson marks the 50th anniversary of these ground-breaking programmes, which began with Supercar in 1961. The set of stamps also includes Royal Mail’s first ‘motion stamps’ on a miniature sheet which using microlenticular printing reveals the Thunderbirds take off when tilted back and forth. Gerry Anderson said: “I feel incredibly proud that my work has been chosen to appear on a set of commemorative stamps and to see actual animation of the opening scenes of Thunderbirds on motion stamps, for me, is wonderful.” The stamps, split between 1st Class and 97p values, feature six of his most popular shows: Supercar, Fireball XL5, Stingray, Thunderbirds, Captain Scarlet and Joe 90, highlighting the ingenious characters and incredible vehicles created by Anderson. For many of course, it’s his most celebrated creation, Thunderbirds, that we remember, especially its dramatic 5! 4! 3! 2! 1! opening sequence. Now people can relive that moment through a four-stamp miniature sheet. The countdown begins with Thunderbird 5 - the Earth-orbiting space station keeping a watchful eye from within the miniature sheet’s border, whilst a moving image of lift off is revealed for Thunderbirds 1, 2, 3 and 4. -

THUNDERBIRDS Written by Peter Hewitt, William Osborne & Michael

THUNDERBIRDS Written by Peter Hewitt, William Osborne & Michael McCullers Animated scenes of the Thunderbirds on various rescues begin to play as some of the cast and crew names show up. NARRATOR From a secret island in the South Pacific, the courageous Tracy family run an organization called International Rescue. When disaster strikes, anywhere in the world, they are always first on the scene. They go by the name they gave their incredible machines, the Thunderbirds. (Counts down numbers and shows corresponding Thunderbirds) Five, four, three, two, one. Thunderbirds are go! Cuts to live action, Alan Tracy is looking out a school window. But in this family of heroes, there is one son left behind. TEACHER So, gentlemen, we all know that A2 plus B2 equals... C2, that's right. But what happens when we bring in Leonardo Da Vinci's E, F and... (Teacher notices Alan looking out window and not paying attention to the lesson) Mr. Tracy! FERMAT Alan. Alan! Alan's head jerks back from the window and to the teacher who is now standing in front of him. TEACHER How kind of you to come back from outer space, Alan. I trust re-entry wasn't too rough? (Chuckles sarcastically and continues sounding even more annoyed) Here on Earth we've been discussing the Pythagorean theorem. Did any of that happen to sink in? ALAN TRACY I was just... TEACHER Apparently not (she picks up his notebook which he has been doodling in) "Thunderbirds are go." Well, I hope you aren't going anywhere special over spring break, Alan. -

In the Great Tradition of Postponed NASA Launches, the York Maze

THUNDERBIRDS ARE GROW! A Thunderbirds fan has created an amazing tribute to 50 years of the iconic show by producing the World’s biggest ever Thunderbird 2, carved into an 15 acre field of growing maize plants near York, England. Tom Pearcy came up with the idea after hearing about the 50th anniversary. Says Tom Pearcy, “As a kid I remember watching Gerry Anderson’s great TV shows like Stingray & Captain Scarlet, but Thunderbirds was my favourite. I wanted to do something big to mark the 50th anniversary. As a child Thunderbird 2 captured my imagination, I think it’s the most iconic of all the Thunderbirds and being green it works perfectly carved into the field of maize plants!” Measuring over 350m (1150ft) long, Thunderbird 2 has been painstakingly carved out of over 1 million living maize plants. It took Mr Pearcy and his team of helpers nearly a week to cut out the 6km of pathways in his 15 acre field near York to form the giant Thunderbird image together with the words ‘Thunderbirds Are 50’. The pathways in the field form an intricate maze for visitors to explore. The York Maze is believed to be the largest maze in Europe and one of the largest in the world. Jamie Anderson, son of Thunderbirds creator the late Gerry Anderson, was so impressed when he heard about Mr Pearcy’s amazing maze that he had to come to York to see it for himself. Jamie took a helicopter flight over the giant 15 acre maize maze to see the design. -

Barry Gray Thunderbirds Are Go / Thunderbird 6 (Original Motion Picture Scores) Mp3, Flac, Wma

Barry Gray Thunderbirds Are Go / Thunderbird 6 (Original Motion Picture Scores) mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Stage & Screen Album: Thunderbirds Are Go / Thunderbird 6 (Original Motion Picture Scores) Country: US Released: 2014 Style: Score MP3 version RAR size: 1138 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1948 mb WMA version RAR size: 1130 mb Rating: 4.9 Votes: 919 Other Formats: VOC AU AAC MOD XM DMF ASF Tracklist 1 Main Titles And Zero X 2 Zero X Theme / Spy On Board 3 Thunderbirds Are Go / Penelope On The Move 4 Journey To Mars And The Swinging Star 5 Fall To Earth / Martian Exploration 6 Rock Snakes / Escape From Mars 7 Time Passes 8 End Titles 9 Plans To Build A Skyship And Thunderbird 6 Main Titles 10 Flight Of The Tiger Moth 11 Operation Escort 12 The Ballroom Jazz 13 Welcome Aboard / Dumping Bodies 14 Skyship Journey–Grand Canyon To Melbourne 15 Indian Street Music 16 Dinner Aboard Skyship One 17 Skyship Journey–Egypt To Switzerland And The Whistle Stop Inn 18 Thunderbirds Are Go / The Trap / Tower Collision 19 Tiger Moth Escape 20 Crash Landing And Conclusion Barcode and Other Identifiers Barcode: 826924130629 Related Music albums to Thunderbirds Are Go / Thunderbird 6 (Original Motion Picture Scores) by Barry Gray Journey - Escape Philip Glass - Roving Mars (Original Motion Picture Soundtrack) Barry Gray - Gerry Anderson's Thunderbirds Are Go The Fabulous Thunderbirds - Portfolio Hans Zimmer - Thelma & Louise / Regarding Henry (The Original Motion Picture Scores) Barry Gray / David Graham - Thunderbird 1 / Ricochet / Captain Scarlet vs. Captain Black - From Gerry Anderson's Thunderbirds (Set 5) Les Baxter & His Orchestra - Les Baxter: At The Movies (Original Film Scores) Infekt - Journey To Mars EP Zombies Of The Stratosphere - Thunderbirds Are Go John Scott - Walking Thunder (Original Motion Picture Score). -

Thunderbirds Lady Penelope Sheet Music

Thunderbirds Lady Penelope Sheet Music Download thunderbirds lady penelope sheet music pdf now available in our library. We give you 1 pages partial preview of thunderbirds lady penelope sheet music that you can try for free. This music notes has been read 2663 times and last read at 2021-09-25 07:05:12. In order to continue read the entire sheet music of thunderbirds lady penelope you need to signup, download music sheet notes in pdf format also available for offline reading. Instrument: Piano Solo Ensemble: Musical Ensemble Level: Intermediate [ READ SHEET MUSIC ] Other Sheet Music Penelope Penelope sheet music has been read 2003 times. Penelope arrangement is for Intermediate level. The music notes has 1 preview and last read at 2021-09-23 02:53:59. [ Read More ] Thunderbirds Are Go Thunderbirds Are Go sheet music has been read 2751 times. Thunderbirds are go arrangement is for Intermediate level. The music notes has 6 preview and last read at 2021-09-23 23:59:52. [ Read More ] Thunderbirds Zero X Theme Thunderbirds Zero X Theme sheet music has been read 5182 times. Thunderbirds zero x theme arrangement is for Intermediate level. The music notes has 2 preview and last read at 2021-09-24 13:29:55. [ Read More ] Thunderbirds Tracy Island Thunderbirds Tracy Island sheet music has been read 2828 times. Thunderbirds tracy island arrangement is for Intermediate level. The music notes has 1 preview and last read at 2021-09-25 07:02:22. [ Read More ] Thunderbirds Joie De Vivre Thunderbirds Joie De Vivre sheet music has been read 5556 times. -

Anderson Entertainment

Anderson Entertainment Anderson Entertainment is the TV & Film production company of the late Gerry Anderson MBE - the man behind a huge number of cult sci-fi and adventure series like Fireball XL5, Stingray, Thunderbirds, Captain Scarlet, UFO, Space:1999, Terrahawks, and Space Precinct among many others. Now headed by Anderson's son Jamie, the company continues to develop Gerry's unfinished film, TV and literary work, as well as maintaining his legacy. In October 2012 they completed a successful Kickstarter campaign to complete and publish Gerry's final series of novels: Gemini Force One. Agents Robert Kirby Associate Agent 0203 214 0800 Kate Walsh [email protected] 020 3214 0884 Publications Children's Publication Notes Details GEMINI FORCE Ben Carrington's dream has become a reality: he's finally a member of Gemini ONE: GHOST Force. But, still suffering from the deaths of his parents, it's a bitter-sweet MINE triumph. 2015 When news reaches GF1 of a gang of illegal 'ghost' miners trapped after a Orion South African mining disaster, Ben is glad to spring into action with the team. But it soon emerges that the company, Auron, doesn't want its miners found. Ben must work out who to trust if he's to ensure that Gemini Force pulls off its most difficult mission yet . Impossible rescues. Maximum risk. This is Gemini Force 1. United Agents | 12-26 Lexington Street London W1F OLE | T +44 (0) 20 3214 0800 | F +44 (0) 20 3214 0801 | E [email protected] Publication Notes Details GEMINI FORCE Impossible rescues - Maximum risk - Gemini Force 1 ONE: BLACK After the tragic death of his father, Ben Carrington's mother teams up with a HORIZON wealthy entrepreneur to form an elite, top-secret rescue organisation - Gemini 2015 Force. -

We Can Each Make a Difference in 2020

We Can Each Make a Difference in 2020 Kluwer Mediation Blog December 28, 2019 John Sturrock (Core Solutions Group) Please refer to this post as:John Sturrock, ‘We Can Each Make a Difference in 2020’, Kluwer Mediation Blog, December 28 2019, http://mediationblog.kluwerarbitration.com/2019/12/28/we-can-each-make-a-difference-in-2020/ One of the most enjoyable aspects of the festive season is receiving and reading books that one might not have come across otherwise. This year, I have been enjoying two quite contrasting works of literature. The first is a Manual for Spectrum Agents (Haynes Publishing) providing “detailed information about the Spectrum organisation”, based on the classic 1960’s Supermarionation television series, Captain Scarlet and the Mysterons. For those of us who grew up with Captain Scarlet (and its predecessor, Thunderbirds), produced by the visionary Gerry and Sylvia Anderson, it is hard to understate to remarkable effect these TV programmes, set 100 years into the future, had on our generation. The book brings it all back. It is a serious exercise in nostalgia. The book reminds us that the basic premise of the TV series was that, by 2068, peace and prosperity had been achieved for the majority of the world’s inhabitants, under the guidance and control of a World Government. A Treaty of Tranquility had been signed in 2046, banning acts of war and aggression between countries and binding them together to fight for one cause – the defence of the Earth. The Republic of Britain was an early dissenter, though it had signed by 2050 following the overthrow of its military dictatorship in 2047. -

THUNDERBIRDS SOLITAIRE GAME Rules 2 3 Emergency Cards the Cards in the Emergency Deck Are Divided Into Three Types: Disaster Cards, Civilian Cards, and Hood Cards

THUNDERBIRDS SOLITAIRE GAME Rules 2 About the game LEAD INTERNATIONAL RESCUE How it works The Thunderbirds Solitaire Game puts you in command of extraordinary Unfolding emergencies across the world are vehicles, powerful technology and heroic characters from the exciting world represented by chains of Disaster cards. When of Thunderbirds. innocent Civilian cards are added to a chain, your priority is to save them by deploying the mighty Thunderbirds. As long as you stay on top of things, success is assured — but be careful not to let a Disaster chain go unchecked, because The mission of International What’s in the box once a chain gathers four cards in a row, the Rescue is to save lives when slightest mistake could spell disaster. disaster strikes. With emergency As well as this rulebook, the Thunderbirds Solitaire Game calls coming in from all over the contains 103 cards and 21 dice: world, your role is to dispatch the right equipment and the right 5 Thunderbird cards 1 Lady Penelope card pilots to each disaster zone, solve 6 Pilot cards 116 Emergency cards tough challenges and rescue victims from mortal danger. 16 Pod cards 21 assorted dice Thunderbird cards These five cards represent the powerful vehicles which lead International Rescue’s day-to-day operations. Each one is designed for a different operational role. During the game, you will decide which vehicle is best suited to which mission, making best use of each Thunderbird’s particular strengths to complete challenges and rescue civilians. Pilot cards These cards represent members of the International Rescue team. -

Television for Children: Problems of National Specificity and Globalisation

Television for children: problems of national specificity and globalisation Book or Report Section Accepted Version Bignell, J. (2011) Television for children: problems of national specificity and globalisation. In: Lesnik-Oberstein, K. (ed.) Children in Culture, Revisited: Further Approaches to Childhood. Palgrave Macmillan, Basingstoke, pp. 167-185. ISBN 9780230275546 Available at http://centaur.reading.ac.uk/21378/ It is advisable to refer to the publisher’s version if you intend to cite from the work. See Guidance on citing . Publisher: Palgrave Macmillan All outputs in CentAUR are protected by Intellectual Property Rights law, including copyright law. Copyright and IPR is retained by the creators or other copyright holders. Terms and conditions for use of this material are defined in the End User Agreement . www.reading.ac.uk/centaur CentAUR Central Archive at the University of Reading Reading’s research outputs online NOTE: This is a chapter published as Bignell, J., ‘Television for children: problems of national specificity and globalisation’ in K. Lesnik-Oberstein (ed.), Children in Culture, Revisited: Further Approaches to Childhood (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan 2011), pp. 167-185. The whole book is available to buy from Palgrave at http://www.palgrave.com/gb/book/9780230275546. My published work is listed and more PDFs can be downloaded at http://www.reading.ac.uk/ftt/about/staff/j-bignell.aspx. Jonathan Bignell Television for children: problems of national specificity and globalisation In the developed nations of Europe, and in the USA, it has long been assumed that television should address children. Thus, notions of what ‘children’ are have been constructed, and children are routinely discussed as an audience category and as a market for programmes. -

Special Assignment

SPECIAL ASSIGNMENT Date: 29th September to 1st October 2017 Venue: Holiday Inn, Manor Lane, Maidenhead, SL6 2RA Friday 29th September 1967, and millions sat in front of their televisions, enthralled by The Mysterons – the first episode of Gerry and Sylvia’s Anderson latest creation, Captain Scarlet And The Mysterons. Fifty years on, and Captain Scarlet fans will be celebrating the 50th anniversary of this ground-breaking series at SPECIAL ASSIGNMENT, Fanderson’s convention for 2017. Plus, of course, over the weekend we’ll be looking at all the other amazing visions of the future that AP Films and Century 21 teams gave us in their productions, including Stingray, Thunderbirds, UFO, Space:1999 and more. Keep an eye on www.fanderson.org.uk for the latest news about SPECIAL ASSIGNMENT. TICKETS Tickets to SPECIAL ASSIGNMENT start at just £55 per person for one day, or £90 for the whole weekend. We’ve managed to keep the ticket price the same as our The Future Is Fantastic! convention in 2015 because we’re a fan club and no-one is taking a salary. Note that Saturday-only or Sunday-only tickets do not include the Saturday evening meal or any other refreshments that are included in the weekend ticket. Ticket prices will rise on 1st May 2017. Fanderson members • Weekend (£90) Saturday only (£55) Sunday only (£55) Not a Fanderson member? Anyone coming to Special Assignment who isn’t already a Fanderson member (even if you’re coming with a club member) must buy a Trial member ticket which includes a trial Fanderson membership at a special price of £10. -

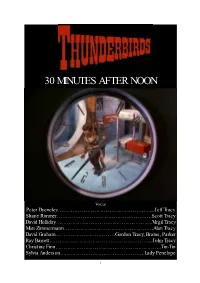

30 Minutes After Noon

30 MINUTES AFTER NOON Voices Peter Dyeneley……………………………...…….…………………...Jeff Tracy Shane Rimmer………………………………………………………..Scott Tracy David Holliday………………………………………….……………..Virgil Tracy Matt Zimmermann…………………………………………………….Alan Tracy David Graham……………………………….….Gordon Tracy, Brains, Parker Ray Barrett………………………………………………..…………...John Tracy Christine Finn……………………………..……..………………………...Tin-Tin Sylvia Anderson………………………………………..………..Lady Penelope 1 SUNSET ON A BIG CITY. OFFICES HAVE JUST CLOSED... A MAN DRIVING BACK HOME, AS MANY OTHERS. 2 UNTIL HIS HEADLIGHTS MAKE HIM SEE A HITCH- HICKING MAN. Hi there... Are you going near Princeton Avenue? Sure! Hop in! 3 That’s real nice of you… I’ve got to get the Doctor to see my wife! I’m sorry to hear that... THE CAR STOPS AT THE REQUE- STED ADDRESS. 4 Thank you! But before I let you go, there’s some- thing I’ve got for you... QUICKLY, THE STRANGER GETS HOLD OF THE DRIVER’S WRIST... 5 What’s this...? Just becau- se I gave you a lift... HARDLY A SIGN OF GRATE- FULNESS. Now listen, Prescott… you work at the Hudson Building, room 1972... In the top dra- wer of your cabinet you’ll find a key to release you... 6 The bracelet is a bomb set for 8:00 o’clock... Leave it in the same dra- wer and get away! Better if you do- n’t waste time...! And don’t try to take it off, it’s made of hydro- chromatised steel! PRESCOTT TURNS THE CAR TO GO BACK AS SOON AS POSSIBLE! 7 LESS THAN A 20 MINUTES TIME. DRIVING SO FAST, HE CAN’T AVOID TO BE NOTICED BY POLICE. 8 Highway Control from car 107… Going in pursuit of a red cabrio on highway 6. -

Sylvia Anderson Headlines at Sci-Fi Weekend

11th March 2014 Sylvia Anderson headlines at sci-fi weekend Cosford Flights of Fantasy - 17th & 18th May FREE entry Special guest talks - advance tickets only This May, the Royal Air Force Museum Cosford will be transporting its visitors back to the 60’s and 70’s with a weekend devoted to classic British sci-fi. This nostalgic event, located in the Museum’s National Cold War Exhibition, will display puppets and memorabilia from iconic science fiction shows created by Gerry and Sylvia Anderson; with visitors having the unique opportunity to view puppets of much loved characters including the Thunderbirds, Joe 90, Steve Zodiac, the heroic pilot of Fireball XL5, Captain Scarlet and his evil nemesis Captain Black, and the Terrahawks, to name but a few. These characters inspired the dreams of a generation of children when the sci-fi series were broadcast into family homes during the 1960’s and 70’s. Many of the well-known puppets on display are original studio puppets which will be shown exclusively for the very first time at this weekend event. Also on display are models, costumes, full sized vehicles and sets from the classic live action shows Space 1999 and UFO. For anyone wishing to take home a piece of memorabilia, trade stands will also be present with associated merchandise from these legendary shows. In addition to the free sci-fi exhibition, very special guest speakers will be holding talks and question & answer sessions for a limited number of visitors. Star guest will be the renowned Sylvia Anderson, co- creator, producer and the voice of Lady Penelope.