Concordia Theological Quarterly

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Church of Sweden Abroad and Its Older Visitors and Volunteers

Behind the Youthful Facade: The Church of Sweden Abroad and Its Older Visitors and Volunteers Annika Taghizadeh Larsson and Eva Jeppsson Grassman Linköping University Post Print N.B.: When citing this work, cite the original article. Original Publication: Annika Taghizadeh Larsson and Eva Jeppsson Grassman, Behind the Youthful Facade: The Church of Sweden Abroad and Its Older Visitors and Volunteers, 2014, Journal of Religion, Spirituality & Aging, (26), 4, 340-356. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/15528030.2014.880774 Copyright: © Taylor & Francis Group, LLC http://www.tandfonline.com/ Postprint available at: Linköping University Electronic Press http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:liu:diva-111215 Behind the youthful façade: the Church of Sweden Abroad and its older visitors and volunteers Abstract This article addresses the role of the Church of Sweden Abroad, with its 45 parishes in foreign countries, for older Swedes who live or stay abroad, permanently or for long or short periods. The article is based on a research project comprising three studies: a qualitative study, an analysis of websites and information material, and an internet-based survey. The results highlight the important role played by the parishes for older visitors, in terms of providing community, support and religious services. However, people above the age of 65 were virtually invisible on the church websites and in other information material. This paradox will be discussed and the concept of ageism is used in the analysis. Keywords: migration, older people, ageism, the Church of Sweden, ethnic congregations Introduction Since the 1990s, a growing body of literature has revealed that migrants may contact and become involved with immigrant religious congregations for a variety of reasons (Cadge & Howard Ecklund, 2006; Furseth, 2008) and that the consequences of such involvement are multifaceted. -

THE MISSIONARY SPIRIT in the AUGUSTANA CHURCH the American Church Is Made up of Many Varied Groups, Depending on Origin, Divisions, Changing Relationships

Augustana College Augustana Digital Commons Augustana Historical Society Publications Augustana Historical Society 1984 The iM ssionary Spirit in the Augustana Church George F. Hall Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.augustana.edu/ahsbooks Part of the History Commons, and the Scandinavian Studies Commons Recommended Citation "The iM ssionary Spirit in the Augustana Church" (1984). Augustana Historical Society Publications. https://digitalcommons.augustana.edu/ahsbooks/11 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Augustana Historical Society at Augustana Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Augustana Historical Society Publications by an authorized administrator of Augustana Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Missionary Sphit in the Augustana Church George F. Hall \ THE MISSIONARY SPIRIT IN THE AUGUSTANA CHURCH The American church is made up of many varied groups, depending on origin, divisions, changing relationships. One of these was the Augustana Lutheran Church, founded by Swedish Lutheran immigrants and maintain ing an independent existence from 1860 to 1962 when it became a part of a larger Lutheran community, the Lutheran Church of America. The character of the Augustana Church can be studied from different viewpoints. In this volume Dr. George Hall describes it as a missionary church. It was born out of a missionary concern in Sweden for the thousands who had emigrated. As soon as it was formed it began to widen its field. Then its representatives were found in In dia, Puerto Rico, in China. The horizons grew to include Africa and Southwest Asia. Two World Wars created havoc, but also national and international agencies. -

Evangelical Lutheran Church in America Archives Global

A Guide to the Microfilm Edition of Evangelical Lutheran Church in America Archives Global Missions, Series 1 Primary Source Media Evangelical Lutheran Church in America Archives Global Missions, Series 1 Primary Source Media Primary Source Media 12 Lunar Drive, Woodbridge, CT 06525 Tel: (800) 444 0799 and (203) 397 2600 Fax: (203) 397 3893 P.O. Box 45, Reading, England Tel (+ 44) 1734 583247 Fax: (+ 44) 1734 394334 ISBN: 978-1-57803-389-6 All rights reserved, including those to reproduce this book or any parts thereof in any form Printed and bound in the United States of America 2007 TABLE OF CONTENTS Scope and Content Note………………………………………………………………….. v Source Note…………………………………………………………………………..… viii Editorial Note………………………………………………………..…………………… ix Reel Index Part 1: American (Danish) Evangelical Lutheran Church ……………………………… 1 Part 2: American Lutheran Church, 1930-1960 ………………………………………... 2 Part 3: General Council [of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in North America] …… 4 Part 4: Iowa Synod [Evangelical Lutheran Synod of Iowa and Other States] ………… 5 Part 5: Joint Synod of Ohio [Evangelical Lutheran Synod of Ohio and Other States] … 6 Part 6: United Lutheran Church in America ……..……………………………….….… 7 Appendix: Administrative Histories……………………………………………….. …..11 SCOPE AND CONTENT NOTE Since 1842, when Rev. J.C.F. Heyer went to India as a missionary of the Pennsylvania Ministerium, representatives of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America (ELCA) and its predecessor bodies have helped spread the Gospel throughout the world. This microfilm collection provides essential and unique research materials for the study of the role of missionary activities in developing countries, the impetus for missionary work, and the development of the Lutheran Church worldwide. -

The Lutheran World Federation

The Lutheran World Federation The LWF is a global communion of Christian churches in the Lutheran tradition. Founded in 1947 in Lund (Sweden), the LWF now has 131 member churches in 72 countries repre- senting over 60.2 million of the nearly 64 million Lutherans worldwide. The LWF acts on behalf of its member churches in areas of common interest such as ecumenical relations, theology, humanitarian assistance, human rights, communication, and the various aspects of mission and development work. Its secretariat is located in Geneva, Switzerland. The Lutheran World Federation / Department for World Service operates programmes in relief, rehabilitation and development in 24 countries. Its man- date is the expression of Christian care to people in need irrespective of race, sex, creed, nationality, religious or political conviction. Lutheran World Federation Phone: (+41-22) 791 61 11 Department for World Service Fax: (+41-22) 798 86 16 150, Route de Ferney PO Box 2100 CH-1211 Geneva 2 Switzerland ACT International is a world-wide network of Churches and their related agencies meeting human need through a coordinated emergency response and a common identity. The ACT network is based in the Lutheran World Federation and the World Council of Churches in Geneva and is a coordinating, rather than an operational, office whose primary functions are to ensure:- ¨ Events that may lead to an emergency intervention are monitored ¨ Rapid Assessment ¨ Coordinated fund-raising ¨ Reporting ¨ Communication and Information flow ¨ Emergency Preparedness ACT represents a move towards coordination and streamlining of existing structures. It is able to meet urgent requests to assist vulnerable groups during sudden emergencies that result from natural or human causes. -

Lutheran Churches in Australia by Jake Zabel 2018

Lutheran Churches in Australia By Jake Zabel 2018 These are all the Lutheran Church bodies in Australia, to the best of my knowledge. I apologise in advance if I have made any mistakes and welcome corrections. English Lutheran Churches Lutheran Church of Australia (LCA) The largest Lutheran synod in Australia, the Lutheran Church of Australia (LCA) was formed in 1966 when the two Lutheran synods of that day, the Evangelical Lutheran Church of Australia (ELCA) and the United Evangelical Lutheran Church in Australia (UELCA), united into one Lutheran synod. The LCA has churches all over Australia and some in New Zealand. The head of the LCA is the synodical bishop. The LCA is also divided in districts with each district having their own district bishop. The LCA is an associate member of both the Lutheran World Federation (LWF) and the International Lutheran Council (ILC). The LCA is a member of the National Council of Churches in Australia. The LCA has official altar-pulpit fellowship with the Evangelical Lutheran Church of Papua New Guinea (ELCPNG) and Gutnius Lutheran Church of Papua New Guinea (GLCPNG) and a ‘Recognition of Relationship’ with the Lutheran Church of Canada (LCC). The LCA also has missions to the Australia Aboriginals. The LCA also has German, Finnish, Chinese, Indonesian and African congregations in Australia, which are considered members of the LCA. The LCA is also in fellowship with German, Latvian, Swedish, and Estonian congregations in Australia, which are not considered members of the LCA. Evangelical Lutheran Congregations of the Reformation (ELCR) The third largest synod in Australia, the Evangelical Lutheran Congregations of the Reformation (ELCR), formed in 1966 from a collection of ELCA congregations who refused the LCA Union of 1966 over the issue of the doctrine of Open Questions. -

Theology of Culture in a Japanese Context: a Believers' Church Perspective

Durham E-Theses Theology of culture in a Japanese context: a believers' church perspective Fujiwara, Atsuyoshi How to cite: Fujiwara, Atsuyoshi (1999) Theology of culture in a Japanese context: a believers' church perspective, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/4301/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 1 Abstract Theology of Culture in A Japanese Context: A Believers' Church Perspective Atsuyoshi Fujiwara This thesis explores an appropriate relationship between Christian faith and culture. We investigate the hallmarks of authentic theology in the West, which offer us criteria to evaluate Christianity in Japan. Because Christian faith has been concretely formed and expressed in history, an analysis and evaluation of culture is incumbent on theology. The testing ground for our research is Japan, one of the most unsuccessful Christian mission fields. -

Church Relations

CHURCH RELATIONS SECTION 9 Interchurch Relationships of the LCMS Interchurch relationships of the LCMS have 11. Independent Evangelical Lutheran Church been growing by leaps and bounds in the last (Germany)* triennium. In addition to our growing family of 12. Evangelical Lutheran Church of Ghana* official “Partner Church” bodies with whom the 13. Lutheran Church in Guatemala* LCMS is in altar and pulpit fellowship, the LCMS 14. Evangelical Lutheran Church of Haiti* also has a growing number of “Allied Church” bodies with whom we collaborate in various 15. Lutheran Church – Hong Kong Synod* ways but with which we do not yet have altar 16. India Evangelical Lutheran Church* and pulpit fellowship. We presently have thirty- 17. Japan Lutheran Church* nine official partnerships that have already been ** For over 13 years, The Lutheran Church—Missouri Synod recognized by the LCMS in convention as well as (LCMS) has encouraged, exhorted, and convened theological good relationships with an additional forty-three discussions with the Japan Lutheran Church (JLC) to uphold the clear teaching of the infallible Word of God, as held by the Allied Church bodies, many of whom are in historic confessional Christian Church, that only men may be various stages of fellowship talks with the LCMS. ordained to the pastoral office, that is, the preaching office. In addition, the LCMS also has fourteen Sadly, tragically, and against the clear teaching of Holy “Emerging Relationships” with Lutheran church Scripture, the JLC in its April 2021 convention codified the bodies that we are getting to know but with ordination of women to the pastoral office as its official doctrine and practice. -

Lutheran – Reformed

The denominational landscape in Germany seems complex. Luthe- ran, Reformed, and United churches are the mainstream Protestant churches. They are mainly organized in a system of regional chur- ches. But how does that look exactly? What makes the German system so special? And why can moving within Germany entail a conversion? Published by Oliver Schuegraf and Florian Hübner LUTHERAN – REFORMED – UNITED on behalf of the Office of the German National Committee A Pocket Guide to the Denominational Landscape in Germany of the Lutheran World Federation Lutheran – Reformed – United A Pocket Guide to the Denominational Landscape in Germany © 2017 German National Committee of the Lutheran World Federation (GNC/LWF) Revised online edition October 2017 Published by Oliver Schuegraf and Florian Hübner on behalf of the Office of the German National Committee of the Lutheran World Federation (GNC/LWF) This booklet contains an up-dated and shortened version of: Oliver Schuegraf, Die evangelischen Landeskirchen, in: Johannes Oeldemann (ed.), Konfessionskunde, Paderborn/Leipzig 2015, 188–246. Original translation by Elaine Griffiths Layout: Mediendesign-Leipzig, Zacharias Bähring, Leipzig, Germany Print: Hubert & Co., Göttingen This book can be ordered for €2 plus postage at [email protected] or downloaded at www.dnk-lwb.de/LRU. German National Committee of the Lutheran World Federation (GNC/LWF) Herrenhäuser Str. 12, 30419 Hannover, Germany www.dnk-lwb.de Content Preface . 5 The Evangelical Regional Churches in Germany . 7 Lutheran churches . 9 The present . 9 The past . 14 The Lutheran Church worldwide . 20 Reformed churches . 23 The present . 23 The past . 26 The Reformed Church worldwide . 28 United churches . -

LWF 2019 Statistics

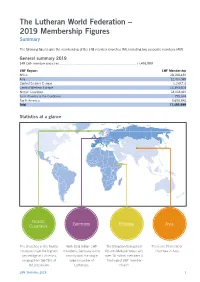

The Lutheran World Federation – 2019 Membership Figures Summary The following figures give the membership of the 148 member churches (M), including two associate members (AM). General summary 2019 148 LWF member churches ................................................................................. 77,493,989 LWF Regions LWF Membership Africa 28,106,430 Asia 12,4 07,0 69 Central Eastern Europe 1,153,711 Central Western Europe 13,393,603 Nordic Countries 18,018,410 Latin America & the Caribbean 755,924 North America 3,658,842 Total 77,493,989 Statistics at a glance Nordic Countries Germany Ethiopia Asia The churches in the Nordic With 10.8 million LWF The Ethiopian Evangelical There are 55 member countries have the highest members, Germany is the Church Mekane Yesus with churches in Asia. percentage of Lutherans, country with the single over 10 million members is ranging from 58-75% of largest number of the largest LWF member the population Lutherans. church. LWF Statistics 2019 1 2019 World Lutheran Membership Details (M) Member Church (AM) Associate Member Church (R) Recognized Church, Congregation or Recognized Council Church Individual Churches National Total Africa Angola ............................................................................................................................................. 49’500 Evangelical Lutheran Church of Angola (M) .................................................................. 49,500 Botswana ..........................................................................................................................................26’023 -

WELS Flag Presentation

WELS Flag Presentation Introduction to Flag Presentation The face of missions is changing, and the LWMS would like to reflect some of those changes in our presentation of flags. As women who have watched our sons and daughters grow, we know how important it is to recognize their transition into adulthood. A similar development has taken place in many of our Home and World mission fields. They have grown in faith, spiritual maturity, and size of membership to the point where a number of them are no longer dependent mission churches, but semi- dependent or independent church bodies. They stand by our side in faith and have assumed the responsibility of proclaiming the message of salvation in their respective areas of the world. Category #1—We begin with flags that point us to the foundations of support for our mission work at home and abroad. U.S.A. The flag of the United States is a reminder for Americans that they are citizens of a country that allows the freedom to worship as God’s Word directs. May it also remind us that there are still many in our own nation who do not yet know the Lord, so that we also strive to spread the Good News to the people around us. Christian Flag The Christian flag symbolizes the heart of our faith. The cross reminds us that Jesus shed his blood for us as the ultimate sacrifice. The blue background symbolizes the eternity of joy that awaits us in heaven. The white field stands for the white robe of righteousness given to us by the grace of God. -

Lutheran World Information

Lutheran World Information The Lutheran World Federation LWI – A Communion of Churches Worldwide Increase Puts LWF 150, route de Ferney P.O. Box 2100 Membership at 66 Million CH-1211 Geneva 2, Switzerland Over One Million New Members in Africa, Dutch Telephone +41/22-791 61 11 Churches’ Merger Adds 2.6 Million to LWF Europe Fax +41/22-791 66 30 E-mail: [email protected] An overall increase of 3.63 million Christians among member churches of the www.lutheranworld.org Lutheran World Federation (LWF) worldwide over a one-year period puts the Editor-in-Chief total membership in the LWF to 65,927,334 in 2004. According to the latest Karin Achtelstetter statistical data from the LWF, the 138 LWF member churches, including eleven [email protected] recognized congregations and one recognized council in 77 countries recorded an increase of more than 5.8 percent. In 2003, LWF member churches around English Editor the world had 62.3 million members, compared to 61.7 million in 2001. Pauline Mumia [email protected] (See page 2) German Editor LWF 2004 Membership Figures Dirk-Michael Grötzsch North America Europe [email protected] 5,182,002 38,594,553 Layout Stéphane Gallay [email protected] Circulation/Subscription Asia Janet Bond-Nash 7,229,661 [email protected] The Lutheran World Information (LWI) is the Latin America information service of the Lutheran World 842,096 Federation (LWF). Africa 14,079,022 Unless specifically noted, material presented © LWF does not represent positions or opinions of the LWF or of its various units. -

How Christians Interpret the Gospel – Religion Online RELIGION ONLINE

5/11/2021 Chapter 2: How Christians Interpret the Gospel – Religion Online RELIGION ONLINE Mythmakers: Gospel, Culture and the Media by William F. Fore Chapter 2: How Christians Interpret the Gospel We live not by things, but by the meaning of things. It is needful to transmit the passwords from generation to generation. -- Antoine de Saint-Expuery The Gospels in the New Testament are only the beginning of "the gospel." "The gospel" has a second source which is not found in the written record of the Bible at all: the historical witness and testimony of almost twenty centuries of Christian believers. While Jesus' life, death, and resurrection are essential elements in the Christian experience, so are the faith responses of Christians throughout history, and both are part of the gospel in our time. For almost two thousand years Christians have been interpreting the gospel in terms of what they knew about the Old and New Testaments, their own cultures, their media, and their experiences. Each generation of believers has incorporated its own life and times into what the gospel means. So we need to know something about that interpretation over the centuries, because it forms a crucial living link between Jesus and ourselves. The Gospel Always Comes Wrapped in a Cultural Context https://www.religion-online.org/book-chapter/chapter-2-how-christians-interpret-the-gospel/ 1/14 5/11/2021 Chapter 2: How Christians Interpret the Gospel – Religion Online As we said in Chapter One, we simply can never expect to transport ourselves back to Urst century Palestine and experience the "real" gospel in its "real" culture.