NSW Empty Container Supply Chain Study Report Prepared for Transport for NSW 5 May 2020

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Patrick Port Botany Terminal, December 2017

Community Feedback Report Port Botany Terminal Patrick HSE Management System Operation Environmental Management Plan Courtesy of Bob Wood - Patrick Port Botany Terminal, December 2017 Report No. PBT_HSE_PLN_11_01_v02 Date Issued: 5 July 2019 CommunityPort Feedback Botany Report Terminal Operation Environmental Management Plan (OEMP) Community Feedback Report DOCUMENT CONTROL Document control shall be in accordance with Patrick’s corporate PAT_HSE_PRO_14_014 Document Management Procedure, ensuring: • The Operation Environmental Management Plan (OEMP or Operation EMP) is maintained and up to date; • The current version of the OEMP is readily available to managers, employees and key stakeholders; and • A copy of the OEMP is retained for a minimum of seven years. Listed below are the four most recent issues for this document. Document History Version Page Issue Date Description of Amendment(s) Prepared By Approved By No. No. 0.7 All 3-Mar-15 Additional edits following DPE comment. A Robinson S Jones 0.8 All 29-Mar-19 Update to new template. Formal Review Marie Gibbs Bruce Guy (draft) conducted as per Condition of Consent 6.5 and includes changes to procedures and practices since the previous review. Issued to NSW Ports for review. 1 All 7-Jun-19 Final revision reissued to DPE. Marie Gibbs Bruce Guy 2 Section 5-Jul-19 Updated with further details related to Marie Gibbs Bruce Guy 6.12 unpacking (opening) a container. A person using Patrick’s documents or data accepts the risk of: • Using the documents or data in electronic form without requesting and checking them for accuracy against the original hard copy version; and • Using the documents or data for any purpose not agreed to in writing by Patrick. -

9.0International Gateways

9.0 International gateways Summary 9.1 Snapshot • Sydney’s international gateways of Port Botany • Even with more freight and airport customers • All of NSW, (including the regions), relies on and Sydney Airport are considered together in this using the rail network, most travel to and from the containerised imports and exports of industrial section due to their close geographic proximity, gateways will remain by road. Major investment is and consumer goods moved through Port Botany. which has implications for the portside and landside needed to augment the existing roads that link to Sydney Airport’s status as Australia’s primary aviation infrastructure of each facility. Port Botany and Sydney Airport. The WestConnex hub benefits the whole state. scheme (refer Section 6) is Infrastructure NSW’s • Port Botany and Sydney Airport have plans to principal response to the transport challenges faced • Sydney’s international gateways are expected to accommodate much of the rapid growth forecast by Sydney’s International Gateways. grow strongly over the next 20 years. for container freight and air travel over the next 20 years. Achieving this primarily requires operational • Once Port Botany reaches capacity, (which is not • Passenger numbers at Sydney Airport are forecast reform to lift productivity, not major capital works. expected to happen during the timeframe of this to double from less than 40 million in 2010 to over 80 Strategy), it is planned for Port Kembla to become million in 2031. • The major infrastructure challenge that Sydney’s NSW’s supplementary container port. International Gateways face is to the landside • Sydney Ports forecasts container movements at Port infrastructure – the roads and railway lines – that • There is no immediate need for supplementary Botany to grow from around 2 million TEUs in 2011 to connect them within the metropolitan area and airport capacity in Sydney. -

Sydney Gateway

Sydney Gateway State Significant Infrastructure Scoping Report BLANK PAGE Sydney Gateway road project State Significant Infrastructure Scoping Report Roads and Maritime Services | November 2018 Prepared by the Gateway to Sydney Joint Venture (WSP Australia Pty Limited and GHD Pty Ltd) and Roads and Maritime Services Copyright: The concepts and information contained in this document are the property of NSW Roads and Maritime Services. Use or copying of this document in whole or in part without the written permission of NSW Roads and Maritime Services constitutes an infringement of copyright. Document controls Approval and authorisation Title Sydney Gateway road project State Significant Infrastructure Scoping Report Accepted on behalf of NSW Fraser Leishman, Roads and Maritime Services Project Director, Sydney Gateway by: Signed: Dated: 16-11-18 Executive summary Overview Sydney Gateway is part of a NSW and Australian Government initiative to improve road and freight rail transport through the important economic gateways of Sydney Airport and Port Botany. Sydney Gateway is comprised of two projects: · Sydney Gateway road project (the project) · Port Botany Rail Duplication – to duplicate a three kilometre section of the Port Botany freight rail line. NSW Roads and Maritime Services (Roads and Maritime) and Sydney Airport Corporation Limited propose to build the Sydney Gateway road project, to provide new direct high capacity road connections linking the Sydney motorway network with Sydney Kingsford Smith Airport (Sydney Airport). The location of Sydney Gateway, including the project, is shown on Figure 1.1. Roads and Maritime has formed the view that the project is likely to significantly affect the environment. On this basis, the project is declared to be State significant infrastructure under Division 5.2 of the NSW Environmental Planning & Assessment Act 1979 (EP&A Act), and needs approval from the NSW Minister for Planning. -

NSW Freight and Ports Plan 2018-2023

NSW Freight and Ports Plan 2018-2023 September 2018 Contents Message from the Ministers 4 Executive Summary – A Plan For Action 2018-2023 6 What the Plan will achieve over the next five years 6 Objective 1: Economic growth 7 Objective 2: Efficiency, connectivity and access 8 Objective 3: Capacity 9 Objective 4: Safety 10 Objective 5: Sustainability 11 Part 1 – Introduction 13 About this Plan 13 Part 2 – Context: The State Of Freight 17 About this chapter 17 The NSW freight and ports sector at glance 17 Greater Sydney production and freight movements 26 The Greater Sydney freight network 28 Regional NSW production and freight movements 36 The regional freight network 39 Part 3 – How We Will Respond To Challenges And Opportunities 45 About this chapter 45 The five objectives 45 Objective 1: Economic growth 47 Objective 2: Efficiency, connectivity and access 51 Objective 3: Capacity 62 Objective 4: Safety 70 Objective 5: Sustainability 73 Part 4 - Implementation Plan 77 Appendix 78 Message from the Ministers The freight industry is the lifeblood of the • Deliver more than $5 billion in committed NSW economy – worth $66 billion to our key infrastructure projects for freight in State economy. From big businesses to NSW. These include $543 million towards farmers, retailers to consumers, we all rely Fixing Country Roads, $400 million on our goods getting to us in a safe and towards Fixing Country Rail, $15 million efficient manner. towards the Fixing Country Rail pilot, $21.5 million towards the Main West rail line, The NSW Freight and Ports Strategy $500 million towards the Sydney Airport released in 2013 was the first long-term Road upgrade, $400 million towards Port freight vision to be produced for NSW, Botany Rail Line duplication, $1171 million which drove targeted investment in both towards the Coffs Harbour Bypass and metropolitan and regional transport $2.2-$2.6 billion towards Sydney Gateway. -

Port Botany Expansion June 2003 Prepared for Sydney Ports Corporation

Port Botany Expansion June 2003 Prepared for Sydney Ports Corporation Visual Impact Assessment Architectus Sydney Pty Ltd ABN 11 098 489 448 41 McLaren Street North Sydney NSW 2060 Australia T 61 2 9929 0522 F 61 2 9959 5765 [email protected] www.architectus.com.au Cover image: Aerial view of the existing Patrick Terminal and P&O Ports Terminal looking south east. Contents 1 Introduction 5 2 Methodology 5 3 Assessment criteria 6 3.1 Visibility 6 3.2 Visual absorption capacity 7 3.3 Visual Impact Rating 8 4 Location 9 5 Existing visual environment 10 5.1 Land form 10 5.2 Land use 10 5.3 Significant open space 11 5.4 Botany Bay 12 5.5 Viewing zones 13 6 Description of the Proposal 28 6.1 New terminal 28 6.2 Public Recreation & Ecological Plan 32 7 Visual impact assessment 33 7.1 Visual impact on views in the immediate vicinity 33 7.2 Visual impact on local views 44 7.3 Visual impact on regional views 49 7.4 Visual impact aerial views 59 7.5 Visual impact on views from the water 65 7.6 Visual impact during construction 74 8 Mitigation measures 75 9 Conclusion 78 Quality Assurance Reviewed by …………………………. Michael Harrison Director Urban Design and Planning Architectus Sydney Pty Ltd …………………………. Date This document is for discussion purposes only unless signed. 7300\08\12\DGS30314\Draft.22 Port Botany Expansion EIS Visual Impact Assessment Figures Figure 1. Location of Port Botany 9 Figure 2. Residential areas surrounding Port Botany 10 Figure 3. -

Existing Port Facilities CHAPTER 3

Existing Port Facilities CHAPTER 3 Summary of key outcomes: Sydney’s ports provide a vital economic gateway for the Australian and NSW economies. In 2001/02, Sydney’s ports handled approximately $42 billion worth of international trade which represents 17% of Australia’s total international trade and 56% of NSW’s international air and sea cargo trade by value. Due to its proximity to the Sydney market, Port Botany is and will remain the primary port for the import and export of containerised cargo in NSW. Currently, over 90% of container trade passing through Sydney’s ports is handled at Port Botany. Port Botany Expansion Environmental Impact Statement – Volume 1 Existing Port Facilities CHAPTER 3 3 Existing Port Facilities 3.1 Role and Significance of Sydney’s Ports The port facilities of Sydney are located at Port Botany and within Sydney Harbour. These ports, along with the airport, are the economic gateways to NSW. This is reflected by the fact that in 2001/02 Sydney’s ports handled approximately $42 billion worth of international trade. This represents: $10,000 for each person in the greater Sydney region, which has a population of close to 4 million; 56% of NSW’s total international air and sea cargo trade by value; and 17% of Australia’s total international trade. Cargo throughput through Sydney’s ports (Sydney Ports Corporation owned and private berths) during 2001/02 was 24.3 million mass tonnes, with containerised cargo accounting for 43.9%. This trade comprised more than 1 million TEUs, 183,000 motor vehicles and about 13.6 million mass tonnes of bulk and general cargo. -

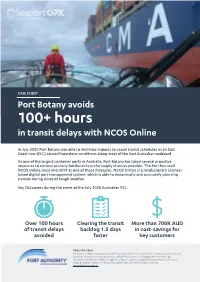

Port Botany Avoids 100+ Hours in Transit Delays with NCOS Online

CASE STUDY Port Botany avoids 100+ hours in transit delays with NCOS Online In July 2020 Port Botany was able to minimize impacts to vessel transit schedules as an East Coast Low (ECL) caused hazardous conditions along most of the East Australian seaboard. As one of the largest container ports in Australia, Port Botany has taken several proactive measures to remove as many bottlenecks in the supply chain as possible. The Port has used NCOS Online since mid-2019 as one of these measures. NCOS Online is a revolutionary science- based digital port management system, which is able to dynamically and accurately plan ship transits during times of rough weather. Key Outcomes during the event of the July 2020 Australian ECL: Over 100 hours Clearing the transit More than 700K AUD of transit delays backlog 1.5 days in cost-savings for avoided faster key customers About the Client Port Botany is a deep-water seaport located in Botany Bay, Sydney. It is one of Australia’s largest container ports and specialises in trade in manufactured products and bulk liquid imports including petroleum and natural gas. Port Authority of New South Wales manages the navigation, security and operational safety needs of commercial shipping in Sydney Harbour, Port Botany, Newcastle Harbour, Port Kembla, Eden and Yamba. portauthoritynsw.com.au East Coast Lows Common during winter months, east coast lows (ECL) are one of the most dangerous weather systems to affect Australia’s east coast. These low- pressure systems have relatively long lifecycles, typically about a week, and can produce gale to storm-force winds, heavy widespread rainfall, and very rough seas and prolonged heavy swells. -

BOTANY RAIL DUPLICATION OCTOBER 2019 Contents

GUIDE TO THE ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT STATEMENT BOTANY RAIL DUPLICATION OCTOBER 2019 Contents About the Botany Rail Duplication Project About this document and ARTC 3 About Botany Rail Duplication 4 Strategic context – Planning for the future NSW Freight and Ports Plan 2018 – 2023 6 Navigating the Future, NSW Ports’ 30 year Master Plan Planning and consultation What is an Environmental Impact Statement? 7 Consultation inputs to the EIS 8 Construction of the project Design and construction methodology 9 Indicative construction program 10 Construction compounds 11 Our environment Traffic, transport and access 12 Noise and vibration 13 Heritage 15 Summary of other key environmental 16 assessments Next steps Make a submission 19 Submissions to the NSW Department of Planning, Industry and Environment should be made on the Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) and not this document, which provides a guide to the EIS only. 2 | October 2019 | Guide to the Environmental Impact Statement | ARTC In May 2018 the Australian Government announced a funding commitment to duplicate the remaining section of single line track between Mascot and Botany, known as the Botany Rail Duplication project. Efficient access to and from Port Botany is critical to the economic growth and prosperity of Sydney. About this document How were the impacts assessed? Following consultation with the community, businesses and stakeholders and detailed environmental investigations an The EIS was prepared through initial community Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) for the project has and stakeholder consultation and detailed specialist been prepared. The Department of Planning, Industry and assessment of key environmental issues, including Environment (DPIE) has placed the Botany Rail Duplication field surveys, data analysis and predictive modelling Project EIS on public exhibition and is inviting submissions. -

NSW Implementation of the National Freight and Supply Chain Strategy and National Action Plan

NSW Implementation of the National Freight and Supply Chain Strategy and National Action Plan November 2019 1 National Critical Area 1: Smarter and targeted infrastructure investment National Action 1.1: Ensure that domestic and international supply chains are serviced by resilient and efficient key freight corridors, precincts and assets Committed/ Initiative Freight and Ports Plan Goal Freight and Ports Plan Initiatives for Timeframe type investigation Port Botany Rail Line Duplication. Through Australian Government funding, duplicate the final three Deliver new infrastructure to kilometres of Port Botany Rail Line, which will allow Immediate increase rail freight capacity freight to be more reliably transported by rail to Infrastructure Committed 0-2 years Initiative ID 31063 metropolitan intermodal terminals from regional intermodal terminals to port (subject to Final Business Case, 3-5 years) Amplification of the Southern Sydney Freight Line. Deliver new infrastructure to Construction of a passing loop at Cabramatta to Immediate increase rail freight capacity Infrastructure Committed support operations at Moorebank Intermodal Terminal 0-2 years Initiative ID 31064 (Subject to Final Business Case, 3-5 years) Outer Sydney Orbital. Freight rail line and motorway Deliver new infrastructure to linking the North West and South West Growth Areas, Medium term increase rail freight capacity connecting with the Western Sydney Airport Growth Infrastructure Committed 5-10 years Initiative ID 31066 Area and future employment lands (10+ years, corridor identified). Western Sydney Freight Line. Freight rail connections to serve the Western Sydney Airport Growth Area; Deliver new infrastructure to connect Port Botany to Western Sydney and Western For Medium term increase rail freight capacity NSW via the Southern Sydney Freight Line; and Infrastructure investigation 5-10 years Initiative ID 31068 support the movement of container and bulk freight by rail across Greater Sydney (10+ years, corridor protection progressing now). -

Sydney Gateway Road Project

Roads and Maritime Services/Sydney Airport Corporation Limited Sydney Gateway Road Project Environmental Impact Statement/ Preliminary Draft Major Development Plan Chapter 1 Introduction Chapter 2 Location and setting November 2019 Environmental Impact Statement / Preliminary Draft Major Development Plan Contents 1. Introduction ......................................................................................................................................... 1.1 1.1 Sydney Gateway ........................................................................................................................ 1.1 1.2 Project overview ........................................................................................................................ 1.3 1.3 Overview of approval requirements ........................................................................................... 1.4 1.4 Purpose and structure of this EIS and preliminary draft MDP ................................................... 1.4 2. Location and setting ........................................................................................................................... 2.1 2.1 The project site for the purposes of the assessment ................................................................. 2.1 2.2 Biophysical and socio-economic environment........................................................................... 2.8 Figures Figure 1.1 Sydney Gateway ...................................................................................................................... -

Economic Analysis of NSW Container and Port Policy Download

NSW Container and Port Policy NSW Container and Port Policy Port of Newcastle March 2018 1 Contents Executive Summary vi Summary Report ix 1 Background 21 2 Port freight in NSW 23 2.1 Regions used in this report 24 2.2 The container supply chain in NSW 24 2.3 Initial container locations in NSW 28 2.4 Import destinations – all freight 29 2.5 Export origins – all freight 30 2.6 Import destinations – containerised freight 31 2.7 Export origins – containerised freight 33 3 Growth challenges 36 3.1 Population and employment growth 37 3.1.1 Demographic forecasts for New South Wales 37 3.1.2 Employment forecasts for New South Wales 38 3.1.3 Regional population projections 39 3.1.4 Regional employment projections 43 3.2 Future port freight volumes 44 3.2.1 Import destinations 47 3.2.2 Export origins 49 4 Planning for growth 52 4.1 Past ports strategy 53 4.1.1 Long Term Transport Master Plan (2012) 53 4.1.2 NSW Freight and Ports Strategy (2013) 54 4.1.3 NSW Ports Master Plan (2015) 54 4.1.4 Summary on existing port plans and strategies 55 4.2 Current NSW Government plans and strategy 55 4.2.1 State Infrastructure Strategy 2018-2038 55 4.2.2 Draft Greater Newcastle Future Transport Plan 56 4.2.3 Freight and Ports Plan 56 4.2.4 Greater Sydney Region Plan 57 4.3 Capital investment to support port growth 57 5 NSW regional Development 61 5.1 NSW regional planning and strategy 62 5.1.1 Jobs for the Future (2016b) 62 5.1.2 Making it Happen in the Regions (2017) 63 5.1.3 Regional Economic Growth Enablers (2017) 63 5.2 Economic priorities of the Hunter -

References to Port Botany in GSC Sydney East Rev Draft

GSC Sydney East Rev Draft -references Port Botany - 30 https://gsc-public-1.s3-ap-southeast-2.amazonaws.com/s3fs-public/draft-eastern-city-district-plan.pdf Pages 6. The District’s freight routes, particularly from Australia’s international gateways of Sydney Airport and Port Botany, will be protected to improve the efficiency of international trade. Industrial and urban services land will be protected from residential encroachment. 13. Map - no T3 – shows former Botany Beach 16 Map - no T3 – shows former Botany Beach 32 Map - no T3 – shows former Botany Beach 37 Map - no T3 – shows former Botany Beach 39. urban renewal opportunities that leverage potential future mass transit to Malabar, Maroubra, La Perouse and Port Botany. 41 Map - no T3 – shows former Botany Beach 47 Map - no T3 – shows former Botany Beach 50. Eastern City District has the highest proportion of knowledge and professional services workers in Greater Sydney. Approximately 62 per cent of the population have achieved a tertiary qualification, one of the highest proportions in Greater Sydney.10 It also has the largest number of start-ups attracted to locations like Pyrmont, Ultimo, Surry Hills, Redfern, Port Botany and Sydney Airport. 51 A further 20 per cent of jobs are within the trade gateways and strategic centres of Port Botany, Sydney Airport, Burwood, Bondi Junction, Eastgardens-Maroubra Junction, Green Square-Mascot, Randwick and Rhodes (refer to Figures 16 and 17).11 Map - no T3 – shows former Botany Beach 53 Eastern Economic Corridor The Eastern Economic Corridor stretches from Macquarie Park, Chatswood, St Leonards and the Harbour CBD to Green Square and the international trade and tourism gateways of Sydney Airport and Port Botany.