Magnetic Field and Permeability of Vacuum

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Basic Magnetic Measurement Methods

Basic magnetic measurement methods Magnetic measurements in nanoelectronics 1. Vibrating sample magnetometry and related methods 2. Magnetooptical methods 3. Other methods Introduction Magnetization is a quantity of interest in many measurements involving spintronic materials ● Biot-Savart law (1820) (Jean-Baptiste Biot (1774-1862), Félix Savart (1791-1841)) Magnetic field (the proper name is magnetic flux density [1]*) of a current carrying piece of conductor is given by: μ 0 I dl̂ ×⃗r − − ⃗ 7 1 - vacuum permeability d B= μ 0=4 π10 Hm 4 π ∣⃗r∣3 ● The unit of the magnetic flux density, Tesla (1 T=1 Wb/m2), as a derive unit of Si must be based on some measurement (force, magnetic resonance) *the alternative name is magnetic induction Introduction Magnetization is a quantity of interest in many measurements involving spintronic materials ● Biot-Savart law (1820) (Jean-Baptiste Biot (1774-1862), Félix Savart (1791-1841)) Magnetic field (the proper name is magnetic flux density [1]*) of a current carrying piece of conductor is given by: μ 0 I dl̂ ×⃗r − − ⃗ 7 1 - vacuum permeability d B= μ 0=4 π10 Hm 4 π ∣⃗r∣3 ● The Physikalisch-Technische Bundesanstalt (German national metrology institute) maintains a unit Tesla in form of coils with coil constant k (ratio of the magnetic flux density to the coil current) determined based on NMR measurements graphics from: http://www.ptb.de/cms/fileadmin/internet/fachabteilungen/abteilung_2/2.5_halbleiterphysik_und_magnetismus/2.51/realization.pdf *the alternative name is magnetic induction Introduction It -

Magnetism Some Basics: a Magnet Is Associated with Magnetic Lines of Force, and a North Pole and a South Pole

Materials 100A, Class 15, Magnetic Properties I Ram Seshadri MRL 2031, x6129 [email protected]; http://www.mrl.ucsb.edu/∼seshadri/teach.html Magnetism Some basics: A magnet is associated with magnetic lines of force, and a north pole and a south pole. The lines of force come out of the north pole (the source) and are pulled in to the south pole (the sink). A current in a ring or coil also produces magnetic lines of force. N S The magnetic dipole (a north-south pair) is usually represented by an arrow. Magnetic fields act on these dipoles and tend to align them. The magnetic field strength H generated by N closely spaced turns in a coil of wire carrying a current I, for a coil length of l is given by: NI H = l The units of H are amp`eres per meter (Am−1) in SI units or oersted (Oe) in CGS. 1 Am−1 = 4π × 10−3 Oe. If a coil (or solenoid) encloses a vacuum, then the magnetic flux density B generated by a field strength H from the solenoid is given by B = µ0H −7 where µ0 is the vacuum permeability. In SI units, µ0 = 4π × 10 H/m. If the solenoid encloses a medium of permeability µ (instead of the vacuum), then the magnetic flux density is given by: B = µH and µ = µrµ0 µr is the relative permeability. Materials respond to a magnetic field by developing a magnetization M which is the number of magnetic dipoles per unit volume. The magnetization is obtained from: B = µ0H + µ0M The second term, µ0M is reflective of how certain materials can actually concentrate or repel the magnetic field lines. -

A Collection of Definitions and Fundamentals for a Design-Oriented

A collection of definitions and fundamentals for a design-oriented inductor model 1st Andr´es Vazquez Sieber 2nd M´onica Romero * Departamento de Electronica´ * Departamento de Electronica´ Facultad de Ciencias Exactas, Ingenier´ıa y Agrimensura Facultad de Ciencias Exactas, Ingenier´ıa y Agrimensura Universidad Nacional de Rosario (UNR) Universidad Nacional de Rosario (UNR) ** Grupo Simulacion´ y Control de Sistemas F´ısicos ** Grupo Simulacion´ y Control de Sistemas F´ısicos CIFASIS-CONICET-UNR CIFASIS-CONICET-UNR Rosario, Argentina Rosario, Argentina [email protected] [email protected] Abstract—This paper defines and develops useful concepts related to the several kinds of inductances employed in any com- prehensive design-oriented ferrite-based inductor model, which is required to properly design and control high-frequency operated electronic power converters. It is also shown how to extract the necessary parameters from a ferrite material datasheet in order to get inductor models useful for a wide range of core temperatures and magnetic induction levels. Index Terms—magnetic circuit, ferrite core, major magnetic loop, minor magnetic loop, reversible inductance, amplitude inductance I. INTRODUCTION Errite-core based low-frequency-current biased inductors F are commonly found, for example, in the LC output filter of voltage source inverters (VSI) or step-down DC/DC con- verters. Those inductors have to effectively filter a relatively Fig. 1. General magnetic circuit low-amplitude high-frequency current being superimposed on a relatively large-amplitude low-frequency current. It is of practitioner. A design-oriented inductor model can be based paramount importance to design these inductors in a way that on the core magnetic model described in this paper which a minimum inductance value is always ensured which allows allows to employ the concepts of reversible inductance Lrevˆ , the accurate control and the safe operation of the electronic amplitude inductance La and initial inductance Li, to further power converter. -

Magnetic Properties of Materials Part 1. Introduction to Magnetism

Magnetic properties of materials JJLM, Trinity 2012 Magnetic properties of materials John JL Morton Part 1. Introduction to magnetism 1.1 Origins of magnetism The phenomenon of magnetism was most likely known by many ancient civil- isations, however the first recorded description is from the Greek Thales of Miletus (ca. 585 B.C.) who writes on the attraction of loadstone to iron. By the 12th century, magnetism is being harnessed for navigation in both Europe and China, and experimental treatises are written on the effect in the 13th century. Nevertheless, it is not until much later that adequate explanations for this phenomenon were put forward: in the 18th century, Hans Christian Ørsted made the key discovery that a compass was perturbed by a nearby electrical current. Only a week after hearing about Oersted's experiments, Andr´e-MarieAmp`ere, presented an in-depth description of the phenomenon, including a demonstration that two parallel wires carrying current attract or repel each other depending on the direction of current flow. The effect is now used to the define the unit of current, the amp or ampere, which in turn defines the unit of electric charge, the coulomb. 1.1.1 Amp`ere's Law Magnetism arises from charge in motion, whether at the microscopic level through the motion of electrons in atomic orbitals, or at macroscopic level by passing current through a wire. From the latter case, Amp`ere'sobservation was that the magnetising field H around any conceptual loop in space was equal to the current enclosed by the loop: I I = Hdl (1.1) By symmetry, the magnetising field must be constant if we take concentric circles around a current-carrying wire. -

Ee334lect37summaryelectroma

EE334 Electromagnetic Theory I Todd Kaiser Maxwell’s Equations: Maxwell’s equations were developed on experimental evidence and have been found to govern all classical electromagnetic phenomena. They can be written in differential or integral form. r r r Gauss'sLaw ∇ ⋅ D = ρ D ⋅ dS = ρ dv = Q ∫∫ enclosed SV r r r Nomagneticmonopoles ∇ ⋅ B = 0 ∫ B ⋅ dS = 0 S r r ∂B r r ∂ r r Faraday'sLaw ∇× E = − E ⋅ dl = − B ⋅ dS ∫∫S ∂t C ∂t r r r ∂D r r r r ∂ r r Modified Ampere'sLaw ∇× H = J + H ⋅ dl = J ⋅ dS + D ⋅ dS ∫ ∫∫SS ∂t C ∂t where: E = Electric Field Intensity (V/m) D = Electric Flux Density (C/m2) H = Magnetic Field Intensity (A/m) B = Magnetic Flux Density (T) J = Electric Current Density (A/m2) ρ = Electric Charge Density (C/m3) The Continuity Equation for current is consistent with Maxwell’s Equations and the conservation of charge. It can be used to derive Kirchhoff’s Current Law: r ∂ρ ∂ρ r ∇ ⋅ J + = 0 if = 0 ∇ ⋅ J = 0 implies KCL ∂t ∂t Constitutive Relationships: The field intensities and flux densities are related by using the constitutive equations. In general, the permittivity (ε) and the permeability (µ) are tensors (different values in different directions) and are functions of the material. In simple materials they are scalars. r r r r D = ε E ⇒ D = ε rε 0 E r r r r B = µ H ⇒ B = µ r µ0 H where: εr = Relative permittivity ε0 = Vacuum permittivity µr = Relative permeability µ0 = Vacuum permeability Boundary Conditions: At abrupt interfaces between different materials the following conditions hold: r r r r nˆ × (E1 − E2 )= 0 nˆ ⋅(D1 − D2 )= ρ S r r r r r nˆ × ()H1 − H 2 = J S nˆ ⋅ ()B1 − B2 = 0 where: n is the normal vector from region-2 to region-1 Js is the surface current density (A/m) 2 ρs is the surface charge density (C/m ) 1 Electrostatic Fields: When there are no time dependent fields, electric and magnetic fields can exist as independent fields. -

Advanced Placement Physics 2 Table of Information

ADVANCED PLACEMENT PHYSICS 2 TABLE OF INFORMATION CONSTANTS AND CONVERSION FACTORS Proton mass, mp = 1.67 x 10-27 kg Electron charge magnitude, e = 1.60 x 10-19 C !!" Neutron mass, mn = 1.67 x 10-27 kg 1 electron volt, 1 eV = 1.60 × 10 J Electron mass, me = 9.11 x 10-31 kg Speed of light, c = 3.00 x 108 m/s !" !! - Avogadro’s numBer, �! = 6.02 � 10 mol Universal gravitational constant, G = 6.67 x 10 11 m3/kg•s2 Universal gas constant, � = 8.31 J/ mol • K) Acceleration due to gravity at Earth’s surface, g !!" 2 Boltzmann’s constant, �! = 1.38 ×10 J/K = 9.8 m/s 1 unified atomic mass unit, 1 u = 1.66 × 10!!" kg = 931 MeV/�! Planck’s constant, ℎ = 6.63 × 10!!" J • s = 4.14 × 10!!" eV • s ℎ� = 1.99 × 10!!" J • m = 1.24 × 10! eV • nm !!" ! ! Vacuum permittivity, �! = 8.85 × 10 C /(N • m ) CoulomB’s law constant, k = 1/4π�0 = 9.0 x 109 N•m2/C2 !! Vacuum permeability, �! = 4� × 10 (T • m)/A ! Magnetic constant, �‘ = ! = 1 × 10!! (T • m)/A !! ! 1 atmosphere pressure, 1 atm = 1.0 × 10! = 1.0 × 10! Pa !! meter, m mole, mol watt, W farad, F kilogram, kg hertz, Hz coulomB, C tesla, T UNIT SYMBOLS second, s newton, N volt, V degree Celsius, ˚C ampere, A pascal, Pa ohm, Ω electron volt, eV kelvin, K joule, henry, H PREFIXES Factor Prefix SymBol VALUES OF TRIGONOMETRIC FUNCTIONS FOR COMMON ANGLES 10!" tera T � 0˚ 30˚ 37˚ 45˚ 53˚ 60˚ 90˚ 109 giga G sin� 0 1/2 3/5 4/5 1 106 mega M 2/2 3/2 103 kilo k cos� 1 3/2 4/5 2/2 3/5 1/2 0 10-2 centi c tan� 0 3/3 ¾ 1 4/3 3 ∞ 10-3 milli m 10-6 micro � 10-9 nano n 10-12 pico p 1 ADVANCED PLACEMENT PHYSICS 2 EQUATIONS MECHANICS Equation Usage �! = �!! + �!� Kinematic relationships for an oBject accelerating uniformly in one 1 dimension. -

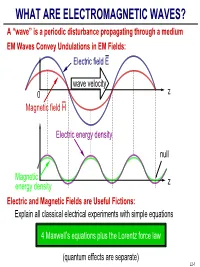

WHAT ARE ELECTROMAGNETIC WAVES? a “Wave” Is a Periodic Disturbance Propagating Through a Medium EM Waves Convey Undulations in EM Fields: Electric Field E

WHAT ARE ELECTROMAGNETIC WAVES? A “wave” is a periodic disturbance propagating through a medium EM Waves Convey Undulations in EM Fields: Electric field E wave velocity 0 z Magnetic field H Electric energy density null Magnetic z energy density Electric and Magnetic Fields are Useful Fictions: Explain all classical electrical experiments with simple equations 4 Maxwell’s equations plus the Lorentz force law (quantum effects are separate) L2-1 WHAT ARE ELECTRIC AND MAGNETIC FIELDS? =+×µ[] Lorentz Force Law: f q() E vo H Newtons E Electric field[] volts/meter; V/m H Magnetic field[] amperes/meter; A/m f Mechanical force[] newtons; N q Charge on a particle[] coulombs; C v Particle velocity vector[] meters/second; m/sec −6 µ×o Vacuum permeability 1.26 10 Henries Electric and Magnetic Fields are what Produce Force f: f== qE when v 0, defining E via an observable f=×µ qvo H when E = 0, defining H via an observable +++ +++ force f -- +++ L2-2 MAXWELL’S EQUATIONS Differential Form: 1Tesla = Webers/m2 = 104 Gauss Faraday's Law:∇× E =−∂ B ∂ t Gauss's Laws ∇• D =ρ Ampere's Law:∇× H = J +∂ D ∂ t ∇• B = 0 E Electric field[] volts/meter; V/m H Magnetic field[] amperes/meter; A/m B Magnetic flux density[] Tesla; T 1 D Electric displacment coulombs/m22 ; C/m J Electric current density amperes/m22 ; A/m ρ Electric charge density coulombs/m33 ; C/m Integral Form: Eds•=−∂∂•() Bt da Dda •=ρ dv ∫∫cA ∫ AV ∫ Hds•=() J +∂∂• Dt da Bda0 •= ∫∫cA ∫ A Stoke’s A Gauss’ V da da Theorem Law A ds L2-3 VECTOR OPERATORS ∇, ×, • “Del” (∇) Operator: Gradient of φ: ∇=xxyyzzˆˆˆ -

Paving Through the Vacuum 3 of the Fermion and Antifermion

Draft to be submitted (will be inserted by the editor) Paving Through the Vacuum C.M.F. Hugon · V. Kulikovskiy the date of receipt and acceptance should be inserted later Abstract Using the model in which the vacuum is filled ΨΨ where Ψ defines the fermion field. Similarly, a tensor h i with virtual fermion pairs, we propose an effective descrip- field can only have a scalar expectation value. tion of photon propagationcompatible with the wave-particle All the virtual particles can exist only inside a Lorentz duality and the quantum field theory. space-time shell defined by the Heisenberg uncertainty prin- In this model the origin of the vacuum permittivity and ciple: ∆x∆p ~ and ∆E∆t ~ . The pairs are CP-symmetric, permeability appear naturally in the statistical description of ≥ 2 ≥ 2 which allow them to keep the total angular momentum,colour the gas of the virtual pairs. Assuming virtual gas in thermal and spin zero values. Considering the Pauli exclusion prin- equilibrium at temperature corresponding to the Higgs field ciple, the virtual fermions in different pairs with the same vacuum expectation value, kT 246.22GeV, the deduced ≈ type and spin cannot overlap, therefore the ensemble of vir- value of the vacuum magnetic permeability (magnetic con- tual particle pairs tends to expand, like a gas in an infinite stant) appears to be of the same order as the experimental vacuum. We expect that the virtual pair gas is in thermal value. One of the features that makes this model attractive equilibrium. The energy exchange between the virtual pairs is the expected fluctuation of the speed of light propagation can be possible due to, for example, the presence of the real that is at the level of σ 1.9asm 1/2. -

A Mechanism Giving a Finite Value to the Speed of Light, and Some Experimental Consequences

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by HAL-IN2P3 A mechanism giving a finite value to the speed of light, and some experimental consequences M. Urban, F. Couchot, X. Sarazin To cite this version: M. Urban, F. Couchot, X. Sarazin. A mechanism giving a finite value to the speed of light, and some experimental consequences. LAL 11-289. Submitted to Eur. Phys. J. B. 2012. <in2p3-00639073v2> HAL Id: in2p3-00639073 http://hal.in2p3.fr/in2p3-00639073v2 Submitted on 13 Sep 2012 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L'archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destin´eeau d´ep^otet `ala diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publi´esou non, lished or not. The documents may come from ´emanant des ´etablissements d'enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche fran¸caisou ´etrangers,des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou priv´es. EPJ manuscript No. (will be inserted by the editor) A model of quantum vacuum as the origin of the speed of light Marcel Urban, Fran¸cois Couchot and Xavier Sarazin LAL, Univ Paris-Sud, CNRS/IN2P3, Orsay, France Received: September 12, 2012 / Revised version: date Abstract. We show that the vacuum permeability µ0 and permittivity ǫ0 may originate from the magneti- zation and the polarization of continuously appearing and disappearing fermion pairs. We then show that if we simply model the propagation of the photon in vacuum as a series of transient captures within these ephemeral pairs, we can derive a finite photon velocity. -

The Inner Connection Between Gravity, Electromagnetism and Light 1 Introduction

Adv. Studies Theor. Phys., Vol. 6, 2012, no. 11, 511 - 527 The Inner Connection Between Gravity, Electromagnetism and Light Faycal Ben Adda New York Institute of Technology [email protected] Abstract In this paper, we prove the existence of an inner connection between gravity and electromagnetism using a different procedure than the stan- dard approaches. Under the assumption of the invariance of the ratio of the Gravitational force to the Electric force in an expanding space- time, we prove that gravity is naturally traceable to the surrounding expanding medium. Keywords: Lorentz Transformations, Gravity, electromagnetism 1 Introduction 1.1 The Laws of Physics It is known that there are four apparently quite distinct ways in which matters interact: gravitationally, electromagnetically, weakly, and strongly, where the first two interactions are long range and manifest themselves in macroscopic size, meanwhile the second two interactions have very short ranges and are only important at the nuclear and sub-nuclear level, where the weak interac- tion is the one responsible for beta decay, while the strong one is responsible for the binding of protons and neutrons to form the nuclei of atoms. Finding a way to relate these four forces to each other was and remains one of the great quests of physicists. The weak force and the electromagnetic force were unified in a theory presented independently by Abdu-Salam, Weinberg and Glashow in 1967 ([7],[11],[13]). However, no success in associating the gravi- tational force with the others has yet been achieved despite the intense effort implemented. Most attempts at unification have been for many years within a frame associating electromagnetism with new geometrical properties of the space-time ([6],[4]). -

Macroscopic Maxwell Equations

J. Förstner How HPC helps exploring electromagnetic near fields Jens Förstner Theoretical Electrical Engineering Outline J. Förstner • Maxwell equations • some analytical solutions – homogeneous media – point-like sources • challenges for wavelength-sized structures • examples from the TET group Maxwell equations J. Förstner Starting point of this talk are the macroscopic Maxwell equations: div 퐷(푟Ԧ, 푡) = 휌(푟Ԧ, 푡) Gauss's law (Electric charges are the source of electro-static fields) Gauss's law for magnetism div 퐵(푟Ԧ, 푡) = 0 (There are no free magnetic charges/monopoles) curl 퐸(푟Ԧ, 푡) = −휕푡퐵(푟Ԧ, 푡) Faraday's law of induction (changes in the magnetic flux electric ring fields) curl 퐻(푟Ԧ, 푡) = 휕 퐷(푟Ԧ, 푡) + 퐽Ԧ (푟Ԧ, 푡) Ampere's law with Maxwell's addition 푡 (currents and changes in the electric flux density magnetic ring fields) 퐸 electric field strength 퐻 magnetic field strength 퐷 electric flux density 퐵 magnetic flux density 푑 휕푡 ≔ 푃Ԧ macroscopic polarization 푃Ԧ magnetic dipole density 푑푡 휌 free electric charge density 퐽Ԧ free electric current density 퐶2 푁 휀 = 8.85 ⋅ 10−12 vacuum permittivity 휇 = 4휋10−7 vacuum permeability 0 푁푚2 0 퐴2 Maxwell theory J. Förstner - magnetism (earth, compass) DC - binding force between electrons & nucleus => atoms pg - binding between atoms => molecules and solids l.j AC circuit - <1 kHz: electricity, LF electronics - antennas, radation: radio, satellites, cell phones, radar - metallic waveguides: TV, land-line communication, power transmission, HF electronics - lasers, LEDs, optical fibers Full range of effects are described by the - medical applications same theory: Maxwell equations However the material response depends - X-Ray scanning strongly on the frequency. -

A Supplementary Discussion on Bohr Magneton Magnetic Fields Arise from Moving Electric Charges. a Charge Q with Velocity V Gives

A Supplementary Discussion on Bohr Magneton Magnetic fields arise from moving electric charges. A charge q with velocity v gives rise to a magnetic field B, following SI convention in units of Tesla, µ qv × r B = 0 , 4π r3 −7 −2 2 where µ0 is the vacuum permeability and is defined as 4π × 10 NC s . Now consider a magnetic dipole moment as a charge q moving in a circle with radius r with speed v. The current is the charge flow per unit time. Since the circumference of the circle is 2πr, and the time for one revolution is 2πr/v, one has the current as I = qv/2πr. The magnitude of the dipole moment is |µ| = I · (area) = (qv/2πr)πr2 = qrp/2m, where p is the linear momentum. Since the radial vector r is perpendicular to p, we have qr × p q µ = = L, 2m 2m where L is the angular momentum. The magnitude of the orbital magnetic momentum of an electron with orbital-angular- momentum quantum l is e¯h 1/2 1/2 µ = [l(l + 1)] = µB[l(l + 1)] . 2me Here, µB is a constant called Bohr magneton, and is equal to −19 −34 e¯h (1.6 × 10 C) × (6.626 × 10 J · s/2π) −24 µB = = −31 = 9.274 × 10 J/T, 2me 2 × 9.11 × 10 kg where T is magnetic field, Tesla. Now consider applying an external magnetic field B along the z-axis. The energy of interaction between this magnetic field and the magnetic dipole moment is e µB EB = −µ · B = Lz · B = BLz.