Prussian Losses Would Have Amounted to 20

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

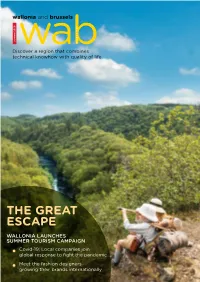

Wabmagazine Discover a Region That Combines Technical Knowhow with Quality of Life

wallonia and brussels summer 2020 wabmagazine Discover a region that combines technical knowhow with quality of life THE GREAT ESCAPE WALLONIA LAUNCHES SUMMER TOURISM CAMPAIGN Covid-19: Local companies join global response to fight the pandemic Meet the fashion designers growing their brands internationally .CONTENTS 6 Editorial The unprecedented challenge of Covid-19 drew a sharp Wallonia and Brussels - Contact response from key sectors across Wallonia. As companies as well as individuals took action to confront the crisis, www.wallonia.be their actions were pivotal for their economic survival as www.wbi.be well as the safety of their employees. For audio-visual en- terprise KeyWall, the combination of high-tech expertise and creativity proved critical. Managing director Thibault Baras (pictured, above) tells us how, with global activities curtailed, new opportunities emerged to ensure the com- pany continues to thrive. Investment, innovation and job creation have been crucial in the mobilisation of the region’s biotech, pharmaceutical and medical fields. Our focus article on page 14 outlines their pursuit of urgent research and development projects, from diagnosis and vaccine research to personal protec- tion equipment and data science. Experts from a variety of fields are united in meeting the challenge. Underpinned by financial and technical support from public authori- ties, local companies are joining the international fight to Editor Sarah Crew better understand and address the global pandemic. We Deputy editor Sally Tipper look forward to following their ground-breaking journey Reporters Andy Furniere, Tomáš Miklica, Saffina Rana, Sarah Schug towards safeguarding public health. Art director Liesbet Jacobs Managing director Hans De Loore Don’t forget to download the WAB AWEX/WBI and Ackroyd Publications magazine app, available for Android Pascale Delcomminette – AWEX/WBI and iOS. -

La Bataille De Ligny

La Bataille de Ligny Règlements Exclusif Pour le Règlement de l’An XXX et Le Règlement des Marie-Louise 2 La Bataille de Ligny Copyright © 2013 Clash of Arms. December 30, 2013 • Général de brigade Colbert – 1re Brigade/5e Division de Cavalerie Légère All rules herein take precedence over any rules in the series rules, • Général de brigade Merlin – 2e Brigade/5e Division de which they may contradict. Cavalerie Légère • Général de brigade Vallin – 1re Brigade/6e Division de 1 Rules marked with an eagle or are shaded with a gray Cavalerie background apply only to players using the Règlements de • Général de brigade Berruyer – 2e Brigade/6e Division de l’An XXX. Cavalerie 3.1.3 Prussian Counter Additions NOTE: All references to Artillery Ammunition Wagons (AAWs,) 3.1.3.1 The 8. Uhlanen Regiment of the Prussian III Armeekorps was ammunition, ricochet fire, howitzers, grand charges and cavalry neither equipped with nor trained to use the lance prior to the advent skirmishers apply only to players using the Règlements de l’An XXX. of hostilities in June 1815. Therefore, remove this unit’s lance bonus and replace it with a skirmish value of (4). 1.0 INTRODUCTION 3.1.3.2 Leaders: Add the following leaders: • General der Infanterie Prinz Friedrich Wilhelm Heinrich La Bataille de Ligny is a simulation of one of the opening battles of August von Preussen – Armee Generalstab the Waterloo campaign of 1815 fought between the Emperor • Oberstleutnant von Sohr – II. Armee-Corps, 2. Kavallerie- Napoléon and the bulk of the French L’Armée du Nord and Field Brigade Marshal Blücher, commander of the Prussian Army of the Lower • Oberst von der Schulenburg – II. -

Waterloo in Myth and Memory: the Battles of Waterloo 1815-1915 Timothy Fitzpatrick

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2013 Waterloo in Myth and Memory: The Battles of Waterloo 1815-1915 Timothy Fitzpatrick Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES WATERLOO IN MYTH AND MEMORY: THE BATTLES OF WATERLOO 1815-1915 By TIMOTHY FITZPATRICK A Dissertation submitted to the Department of History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Fall Semester, 2013 Timothy Fitzpatrick defended this dissertation on November 6, 2013. The members of the supervisory committee were: Rafe Blaufarb Professor Directing Dissertation Amiée Boutin University Representative James P. Jones Committee Member Michael Creswell Committee Member Jonathan Grant Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members, and certifies that the dissertation has been approved in accordance with university requirements. ii For my Family iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank Drs. Rafe Blaufarb, Aimée Boutin, Michael Creswell, Jonathan Grant and James P. Jones for being on my committee. They have been wonderful mentors during my time at Florida State University. I would also like to thank Dr. Donald Howard for bringing me to FSU. Without Dr. Blaufarb’s and Dr. Horward’s help this project would not have been possible. Dr. Ben Wieder supported my research through various scholarships and grants. I would like to thank The Institute on Napoleon and French Revolution professors, students and alumni for our discussions, interaction and support of this project. -

Belgian Laces

Belgian Laces Rolle Volume 22#86 March 2001 BELGIAN LACES Official Quarterly Bulletin of THE BELGIAN RESEARCHERS Belgian American Heritage Association Our principal objective is: Keep the Belgian Heritage alive in our hearts and in the hearts of our posterity President/Newsletter editor Régine Brindle Vice-President Gail Lindsey Treasurer/Secretary Melanie Brindle Deadline for submission of Articles to Belgian Laces: January 31 - April 30 - July 31 - October 31 Send payments and articles to this office: THE BELGIAN RESEARCHERS Régine Brindle - 495 East 5th Street - Peru IN 46970 Tel/Fax:765-473-5667 e-mail [email protected] *All subscriptions are for the calendar year* *New subscribers receive the four issues of the current year, regardless when paid* ** The content of the articles is the sole responsibility of those who wrote them* TABLE OF CONTENTS Letter from the Editor - Membership p25 Ellis Island American Family Immigration History Center: p25 "The War Volunteer” by Caspar D. p26 ROCK ISLAND, IL - 1900 US CENSUS - Part 4 p27 "A BRIEF STOP AT ROCK ISLAND COUNTY HISTORICAL SOCIETY,"by Michael John Neill p30 Declarations of Intention, Douglas Co. Wisconsin, Part 1, By John BUYTAERT, MI p32 History of Lace p35 DECLARATIONS OF INTENTION — BROWN COUNTY, WISCONSIN, by MaryAnn Defnet p36 In the Land of Quarries: Dongelberg-Opprebais, by Joseph TORDOIR p37 Belgians in the United States 1990 Census p39 Female Labor in the Mines, by Marcel NIHOUL p40 The LETE Family Tree, Submitted by Daniel DUPREZ p42 Belgian Emigrants from the Borinage, Combined work of J. DUCAT, D. JONES, P.SNYDER & R.BRINDLE p43 The emigration of inhabitants from the Land of Arlon, Pt 2, by André GEORGES p45 Area News p47 Queries p47 Belgian Laces Vol 23-86 March 2001 Dear Friends, Just before mailing out the December 2000 issue of Belgian Laces, and as I was trying to figure out an economical way of reminding members to send in their dues for 2001, I started a list for that purpose. -

Rethinking Waterloo from Multiple Perspectives by FRANCESCO SCATIGNA

EUROCLIO presents Teaching 1815 Rethinking Waterloo from Multiple Perspectives by FRANCESCO SCATIGNA with the high patronage of JUNE 2015: bicentenary of the Battle of Waterloo Copyright This publication is published under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC BY 4.0) — Unless indicated otherwise, the images used in this publication are in the public domain Published by EUROCLIO - European Association of History Education Under the patronage of Layout & Graphics IMERICA Giovanni Collot, Nicolas Lozito and Federico Petroni www.imerica.it Printed in June 2015 Acknowledgements his publication has been developed for EUROCLIO – European Association of History Educators Tby Francesco Scatigna (Historiana Editor) with the support of Joke van der Leeuw-Roord (EUROCLIO Founder and Special Advisor). The publication makes use of contributions of participants to and partners (Waterloo200 and the Waterloo Belgium Committee) in the international Seminar “Teaching 1815. Rethinking the Battle of Waterloo from Multiple Perspectives”. The publication is made possible thanks to the support of the Province of the Brabant Walloon. EUROCLIO would like to thank all contributors to this publication and its partners in the organisation of the seminar. The work of EUROCLIO is made possible through the support of the Europe for Citizens programme of the European Union. TEACHING 1815: Rethinking Waterloo from Multiple Perspectives | 3 table of chapter 1 chapter 2 Introduction Remembering Waterloo and the Napoleonic wars page page 6 8 4 | TEACHING 1815: Rethinking Waterloo from Multiple Perspectives contents chapter 3 chapter 4 How to make Conclusions teaching & about it Endnotes attractive page page 16 28 TEACHING 1815: Rethinking Waterloo from Multiple Perspectives | 5 introduction “The history of a battle is not unlike the history of a ball. -

La Bataille De Ligny II

La Bataille de Ligny II Règlements Exclusif Pour le Règlement de l’An XXX et Le Règlement des Marie-Louise 2 La Bataille de Ligny Copyright © 2016 Clash of Arms. March 26, 2017 attacking unit actually is, only 6 parts/increments belonging to the unit may assault). All rules herein take precedence over any rules in the series rules, Example: a battalion with 10 increments and a melee value of 25 which they may contradict. assaults the hex. Only 6/10ths of the unit counts for its pre-melee Rules marked with an eagle or are shaded with a gray morale check, and 6/10ths of its melee strength can be used in the background apply only to players using the Règlements melee. This particular unit would have a melee value of 15 (25/10 de l’An XXX. = 2.5, 2.5 x 6 = 15). All Churches, Walled Farms and Chateaus are presumed to have at least one such aperture (some may have two). NOTE: All references to Artillery Ammunition Wagons (AAWs,) Though the artwork for the gate may be difficult to spot at first ammunition, ricochet fire, howitzers, grand charges and cavalry glance, only up to six increments may assault one of these skirmishers apply only to players using the Règlements de l’An structures, and the assault must be made against the hex-side XXX. indicated by the gateway (or entranceway if it is a church: The entranceway to a church is always just beneath the steeple.) If the structure has two gates then that hex may be assaulted by up to 12 1.0 INTRODUCTION increments, but the assaults must be against the hex-sides La Bataille de Ligny is a simulation of one of the opening battles containing the aperture, and only up to 6 increments may assault of the Waterloo campaign of 1815 fought between the Emperor each indicated hex-side. -

WATERLOO 1815 (2) Ligny

WATERLOO 1815 (2) Ligny JOHN FRANKLIN ILLUSTRATED BY GERRY EMBLETON © Osprey Publishing • www.ospreypublishing.com CAMPAIGN 277 WATERLOO 1815 (2) Ligny JOHN FRANKLIN ILLUSTRATED BY GERRY EMBLETON Series editor Marcus Cowper © Osprey Publishing • www.ospreypublishing.com CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 4 Napoleon escapes from the island of Elba The long march to Paris and return to power CHRONOLOGY 9 OPPOSING COMMANDERS 13 French commanders Prussian commanders OPPOSING FORCES 18 The command and composition of the French Army The command and composition of the Prussian Army Orders of battle OPPOSING PLANS 29 THE CAMPAIGN OPENS 30 The French advance and the capture of Charleroi The Prussian withdrawal and the combat at Gilly Movements on the morning of 16 June Important decisions for the three commanders The struggle for the crossroads commences Final preparations at Fleurus and Sombreffe Vandamme attacks the village of St Amand Gérard begins the offensive against Ligny Orders to envelop Brye and St Amand Zieten launches a counterattack at Ligny Blücher intervenes in the fighting at St Amand The contest escalates at St Amand la Haie Urgent reinforcements bolster the attacks II Korps enters the fray at Wagnelée A column approaches from Villers Perwin Gneisenau sends a messenger to Quatre Bras Fateful decisions in the heat of battle Determined resistance at St Amand and Ligny Napoleon orders the Garde Impériale to attack Cavalry charges in the fields before Brye The Prussians retreat north towards Tilly Wellington holds the French at Quatre Bras AFTERMATH 90 THE BATTLEFIELD TODAY 92 FURTHER READING 94 INDEX 95 © Osprey Publishing • www.ospreypublishing.com INTRODUCTION King Louis XVIII and the victorious coalition armies were welcomed enthusiastically by the Parisians when they entered the French capital in the spring of 1814, following Napoleon’s enforced abdication and exile. -

Presentation of Charleroi

PRESENTATION OF CHARLEROI C.E.C.S. La Garenne Welcome to Charleroi… Charleroi is the biggest city in Wallonia (the French-speaking part of Belgium) and the third-biggest city in Belgium. Statistics Surface : 102 km² 57% urban area 43% rural area Population : 206,898 inhabitants A privileged situation in the heart of Europe… As the economic and cultural centre of a conurbation of nearly half a million inhabitants, the city of Charleroi is an important centre for communications and transport by motorway and rail and on the river Sambre. As the gateway to the Ardennes it is favourably located fifty kilometres (50 km) south of Brussels, the European capital, and one hundred kilometres (100 km) east of the important city of Lille. Charleroi has also a rapidly developing regional airport, Brussels South Charleroi Airport. Charleroi is also the sister city of several other cities around the world. Pittsburgh, USA Himeji, Japan Sélestat, Saint-Junien, France Donetsk, Ukraine Casarano, Follonica, Schramberg, Waldkirch, Italy Germany A short history of Charleroi… In 1666, the Spanish built a fortress on a headland overlooking the valley of the Sambre. The stronghold was named Charleroy to glorify Charles II, the infant King of Spain. The following year, the fortress was taken by French armies and it was under French occupation that fortifications were completed and extended by Vauban. Louis XIV, who wanted to promote the development of the new town, granted its inhabitants privileges. In 1678, under the treaty of Nijmegen, Charleroi was given back to Spain. A first industrial change based on coal, iron and glass industries brought about a rise in Charleroi’s population. -

Chapter 26 the Approach to Battle: Sombreffe, Morning, 16 June

Chapter 26 The Approach to Battle Sombreffe, Morning, 16 June I THE PRUSSIAN HIGH COMMAND had reached Sombreffe in the afternoon of 15 June. The site had been carefully chosen, for the entire position had been thoroughly studied by the army staff in earlier months, although apparently some were doubtful of it as a battleground. Many years later Nostitz, who in 1815 was a major and Blücher’s ADC, claimed that, the danger of accepting battle in the position of Sombreffe had often been put forward by many persons, yet Generals von Gneisenau and von Grolman adhered firmly to the idea. Count Groeben [staff, Reserve Cavalry, I Corps] had carefully reconnoitred and surveyed the chosen battlefield, and had described in such vivid colours its many advantages as to have given rise to an almost fanatical passion for it, which the objections put forward by other members of headquarters, among them myself, could in no way modify.1 Blücher intended to give battle there on 16 June – it was to be the decisive day.2 The site and the timing highlight clearly the problem of the inter-allied arrange ments. Wellington’s principles for a defence were: to hold firmly strong points like Mons or Ath in order to divert or slow a French advance, to keep the field army well back from the frontier, and to launch a counter- offensive on about the third day of operations, having meanwhile given the two allies time to unite. The Prussians, on the other hand, had placed one quarter of their army close to the frontier, and had chosen a fighting position for their entire force only a few miles behind it, aiming at a battle on the second day. -

The Battle of Ligny 16 June, 1815 a Grande Armée Scenario by Lloyd Eaker

The Battle Of Ligny 16 June, 1815 A Grande Armée scenario by Lloyd Eaker As Napoleon opened his 1815 offensive into Belgium he rapidly began to squander the advantages of interior lines and strategic surprise. Splitting his army with a smaller wing under Ney to take the crossroads of Quatre Bras, Napoleon planned to assemble the main body to strike the Prussians at Ligny. But Ney bungled the Quatres Bras operation, Napoleon was unable to assemble his entire force, and the Prussians put up a ferocious resistance. As evening fell, Napoleon committed his Guard for a final assault that broke the Prussian lines. But the late hour and French exhaustion meant that the Prussians got away without a serious pursuit, and Napoleon seemed unable or unwilling to organize one until the next day, by which time it was too late. Napoleon had won his last victory. The Scenario: The Weather is normal and variable. The ground is Hard. The game begins on turn 4, and the basic length is 8. The French Army is “Fair” Its break point is 13. The Prussian Army is “Fair”. Its break point is 16. Alternative Lignys, Play-Balancing, and What-Ifs: Both sides were expeecting reinforcements that never came. Aside from altering the weather or generals’ abilities, the following Force additions could make for a radical transformation of the game. In each case, these are Forces which appeared two days later at Waterloo, so players should copy the Force rosters and labels from the Waterloo scenario in the Grande Armée rulebook. 1. D’Erlon The French I Corps was marching and countermarching between the battles of Ligny and Quatre Bras, responding to Napoleon and Ney’s contradictory orders. -

Observations. Blücher's Retreat. the Situation of the Prussian Army

Observations. Blücher’s retreat. The situation of the Prussian army during the night of the 16th of June. 1 As a result of the French breakthrough at Ligny, the majority of the 1st and 2nd corps instinctively gave way to the north, across the Namur road, across the fields and along the Roman road. Though the situation was most serious, it was possible for Gneisenau to issue instructions to lead the retreating troops towards Tilly, a village about four kilometres north of Brye. By then it was somewhere around 9 p.m. Thanks to the absence of a French pursuit it was possible to cover this retreat with a rear- guard at Brye, which kept its position until about midnight. By that time, most of the 1st and 2nd corps – though shaken and mixed - had been assembled between Tilly and Gentinnes. 2 It had been Gneisenau’s intention to draw Thielmann’s corps to Tilly as well, but this commander decided otherwise. For Thielmann, Gembloux had been advised as a possible alternative and this is what he chose for. This most probably had to do with the fact that he feared the French would be a threat, by pushing further north between him and the other two corps which had been involved in the battle. It was for the 3rd corps possible to assemble in rear of the crossing of Point du Jour and to pull back from there the next morning to Gembloux, while leaving a rear-guard at Sombreffe. This stood there until about the same time as the one at Brye. -

Wallonia in the Wars

SECOND WORLD WAR FIRST WORLD WAR Explore Hitler’s secret hideout Uncover poignant stories of conflict and go on the trail of the battle and comradeship at ruined fortresses of the Bulge and moving memorials (© Bastogne War Museum) © Fort Loncin WALLONIA IN THE WARS EXPLORE THE WATERLOO BATTLEFIELD Follow in the footsteps of Napoleon and Wellington at a place that changed the course of history 02 / WELCOME / WALLONIA BELGIUM TOURISM WALLONIA BELGIUM TOURISM / WELCOME / 03 Welcome UNCOVER A WEALTH OF WARTIME HISTORY IN SCENIC SOUTHERN BELGIUM xploring Wallonia’s wooded hills and rolling fields dotted E with farmhouses, it’s hard to imagine a more peaceful spot. Yet, dig a little deeper and you’ll quickly discover that these tranquil forests and farmlands hide a wealth of secret wartime history. It was in Wallonia that Napoleon’s army – hellbent on victory, yet destined for disaster – finally met its match at Waterloo. It was in Wallonia that the very first and very last British soldiers died on the western front during the First World War. And it was in Wallonia that Hitler’s last big chance to crush and conquer Europe was finally thwarted. All of this turbulent history is still very much alive here. Whether visiting a major museum or stopping P. 04 P. 11 P. 16 by a remote hamlet, you’ll find passionate locals eager to share NAPOLEON’S WATERLOO SUNSET REFLECT AND REMEMBER GERMANY’S LAST GAMBLE their region’s stories, both tragic and Napoleonic Wars First World War Second World War heroic. From farmhouses pockmarked Be transported to the heart of the Uncover poignant stories of conflict Explore the Ardennes forest on the trail with bullet holes, to rifles embedded battle at Waterloo and comradeship at Ploegsteert of the battle of the Bulge in tree roots, history is hard-wired into the landscape here.