Childhood Memories of Post-War Merseyside: Exploring the Impact of Memory Sharing Through an Oral History and Reminiscence Work Approach

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PEN (Organization)

PEN (Organization): An Inventory of Its Records at the Harry Ransom Center Descriptive Summary Creator: PEN (Organization) Title: PEN (Organization) Records Dates: 1912-2008 (bulk 1926-1997) Extent: 352 document boxes, 5 card boxes (cb), 5 oversize boxes (osb) (153.29 linear feet), 4 oversize folders (osf) Abstract: The records of the London-based writers' organizations English PEN and PEN International, founded by Catharine Amy Dawson Scott in 1921, contain extensive correspondence with writer-members and other PEN centres around the world. Their records document campaigns, international congresses and other meetings, committees, finances, lectures and other programs, literary prizes awarded, membership, publications, and social events over several decades. Call Number: Manuscript Collection MS-03133 Language: The records are primarily written in English with sizeable amounts in French, German, and Spanish, and lesser amounts in numerous other languages. Non-English items are sometimes accompanied by translations. Note: The Ransom Center gratefully acknowledges the assistance of the National Endowment for the Humanities, which provided funds for the preservation, cataloging, and selective digitization of this collection. The PEN Digital Collection contains 3,500 images of newsletters, minutes, reports, scrapbooks, and ephemera selected from the PEN Records. An additional 900 images selected from the PEN Records and related Ransom Center collections now form five PEN Teaching Guides that highlight PEN's interactions with major political and historical trends across the twentieth century, exploring the organization's negotiation with questions surrounding free speech, political displacement, and human rights, and with global conflicts like World War II and the Cold War. Access: Open for research. Researchers must create an online Research Account and agree to the Materials Use Policy before using archival materials. -

Prof Michael Turner 18.10.17

Wednesday 18 October 2017 Michael Turner UNESCO Chair in Urban Design and Conservation Studies Bezalel Academy of Arts and Design, Jerusalem 1945 - Why the conflict? • Utopias/visions • Values and interpretations • Generation gaps and changes • Competing interests • Process and project • Short-term / long-term • Lack of tools 1972 - Resolving/containing the conflict • Managing change • Accepting diversity • Sharing benefits • Participatory processes • Sustainable development • Inclusive, safe, resilient and sustainable Utopia Wikipedia Thomas More William Morris Ebenezer Howard Utopia News from Nowhere To-morrow: 1516 1890 A Peaceful Path to Real Reform 1898 Liverpool – 19th century Industrial visions Port Sunlight Village 1888 wikipedia wikipedia Pinterest Liverpool Museum Liverpool Liverpool utopias – 20th century Wavertree Garden Suburb Speke Estate Runcorn New Town 1910 1930 1964 Wikipedia http://www.liverpool-city-group.com/ Rebuilding post WWII - utopias Wars Socio-economic changes The devastation in Liverpool docks after the ammunition ship The Albert Dock fell into disuse in the 1970s, as shown in the 1975 'Malakand' blew up after catching fire on the night of 3rd May 1941. snap above. Part of the Albert Dock failed to be restored from the damage of the Liverpool Blitz 1941. Once welcoming ships into the port every day, the docks are derelict, with not a sign of life to be seen. A year later, the Albert Dock was a conservation area. Signature’s Liverpool - source: www.porterfolio.com World War II reconstruction East Europe - Warsaw -

Military History Anniversaries 16 Thru 31 August

Military History Anniversaries 16 thru 31 August Events in History over the next 15 day period that had U.S. military involvement or impacted in some way on U.S military operations or American interests Aug 16 1777 – American Revolution: Battle of Bennington » The Battle took place in Walloomsac, New York, about 10 miles from its namesake Bennington, Vermont. A rebel force of about 1,500 men, primarily New Hampshire and Massachusetts militiamen, led by General John Stark, and reinforced by Vermont militiamen led by Colonel Seth Warner and members of the Green Mountain Boys, decisively defeated a detachment of General John Burgoyne's army led by Lieutenant Colonel Friedrich Baum, and supported by additional men under Lieutenant Colonel Heinrich von Breymann at Walloomsac, New York. After a rain-caused standoff, Brigadier General John Stark's men enveloped Baum's position, taking many prisoners, and killing Baum. Reinforcements for both sides arrived as Stark and his men were mopping up, and the battle restarted, with Warner and Stark driving away Breymann's reinforcements with heavy casualties. The battle reduced Burgoyne's army in size by almost 1,000 troops, led his Indian support to largely abandon him, and deprived him of much-needed supplies, such as mounts for his cavalry regiments, draft animals and provisions; all factors that contributed to Burgoyne's eventual defeat at the Battle of Saratoga. Aug 16 1780 – American Revolution: Continentals routed at Battle of Camden SC » American General Horatio Gates suffers a humiliating defeat. Despite the fact that his men suffered from diarrhea on the night of 15 AUG, caused by their consumption of under-baked bread, Gates chose to engage the British on the morning of the 15th. -

Liverpool Trade Walk

Stories from the sea A free self-guided walk in Liverpool .walktheworld.or www g.uk Find Explore Walk 2 Contents Introduction 4 Route overview 5 Practical information 6 Detailed maps 8 Commentary 10 Credits 38 © The Royal Geographical Society with the Institute of British Geographers, London, 2012 Walk the World is part of Discovering Places, the London 2012 Cultural Olympiad campaign to inspire the UK to discover their local environment. Walk the World is delivered in partnership by the Royal Geographical Society (with IBG) with Discovering Places (The Heritage Alliance) and is principally funded by the National Lottery through the Olympic Lottery Distributor. The digital and print maps used for Walk the World are licensed to RGS-IBG from Ordnance Survey. 3 Stories from the sea Discover how international trade shaped Liverpool Welcome to Walk the World! This walk in Liverpool is one of 20 in different parts of the UK. Each walk explores how the 206 participating nations in the London 2012 Olympic and Paralympic Games have been part of the UK’s history for many centuries. Along the routes you will discover evidence of how many Olympic and Paralympic countries have shaped our towns and cities. Tea from China, bananas from Jamaica, timber from Sweden, rice from India, cotton from America, hemp from Egypt, sugar from Barbados... These are just some of the goods that arrived at Liverpool’s docks. In the A painting of Liverpool from circa 1680, nineteenth century, 40 per cent of the world’s thought to be the oldest existing depiction of the city trade passed through Liverpool. -

85 Brt - 72 Net - 140 Dw

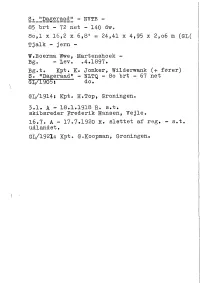

S^o^^Dageraad*^ - WVTB - 85 brt - 72 net - 140 dw. 8o,l x 16,2 x 6,8' = 24,41 x 4,95 x 2,o6 m (GL( Tjalk - jern - W.Boerma Wwe, Martenshoek - Bg. - lev. .4.1897. Bg.t. Kpt. Ko Jonker, Wilderwank (+ fører) S. "Dageraad" - NLTQ - 8o brt - 67 net GI/1905: do. GL/1914: KptO H.Top, Groningen. 3.1. A - 18.1.1918 R. s.t. skibsreder Frederik Hansen, Vejle, 16.7. A - 17.7.1920 R. slettet af reg. - s.t. udlandet. Gl/1921: Kpt. G.Koopman, Groningen. ^Dagmar^ - HBKN - , 187,81 hrt - 181/173 NRT - E.C. Christiansen, Flenshurg - 1856, omhg. Marstal 1871. ex "Alma" af Marstal - Flb.l876$ C.C.Black, Marstal. 17.2.1896: s.t. Island - SDagmarS - NLJV - 292,99 brt - 282 net - lo2,9 x 26,1 x 14,1 (KM) Bark/Brig - eg og fyr - 1 dæk - hækbg. med fladt spejl - middelf. bov med glat stævn. Bg. Fiume - 1848 - BV/1874: G. Mariani & Co., Fiume: "Fidente" - 297 R.T. 29.8.1873 anrn. s.t. partrederi, Nyborg - "DagmarS - Frcs. 4o.5oo mægler Hans Friis (Møller) - BR 4/24, konsul H.W. Clausen - BR fra 1875 6/24 købm. CF. Sørensen 4/24 " Martin Jensen 4/24 skf. C.J. Bøye 3/24 skf. B.A. Børresen - alle Nyborg - 3/24 29.12.1879: Forlist p.r. North Shields - Tuborg havn med kul - Sunket i Kattegat ca. 6 mil SV for Kråkan, da skibet ramtes af brådsø, der knækkede alle støtter, ramponerede skibets ene side, knuste båden og ødelagde pumperne. -

Published by a Cc Art Books 2020 a C C Ar T Books

PUBLISHED BY ACC ART BOOKS 2020 ACC ART BOOKS PUBLISHED BY ACC ART BOOKS 2020 • Iconic portraits and contact sheets from Goldfinger, Diamonds are Forever, Live and Let Die, Golden Eye and the Bond spoof, Casino Royale • Contributions from actors including George Lazenby and Jane Seymour • Includes a foreword by Robert Wade and Neal Purvis, screenwriters for the latest Bond film, No Time to Die Bond Photographed by Terry O’Neill The Definitive Collection James Clarke Terry O’Neill was given his first chance to photograph Sean Connery as James Bond in the film Goldfinger. From that moment, O’Neill’s association with Bond was made: an enduring legacy that has carried through to the era of Daniel Craig. It was O’Neill who captured gritty and roguish pictures of Connery on set, and it was O’Neill who framed the super-suave Roger Moore in Live and Let Die. His images of Honor Blackman as Pussy Galore are also important, celebrating the vital role of women in the James Bond world. But it is Terry O’Neill’s casual, on- set photographs of a mischievous Connery walking around the casinos of Las Vegas or Roger Moore dancing on a bed with co-star Madeline Smith that show the other side of the world’s most recognisable spy. Terry O’Neill opens his archive to give readers - and viewers - the chance to enter the dazzling world of James Bond. Lavish colour and black and white images are complemented by insights from O’Neill, alongside a series of original essays on the world of James Bond by BAFTA-longlisted film writer, James Clarke; and newly-conducted interviews with a number of actors featured in O’Neill’s photographs. -

Oversigt Over Tildelinger (Pdf)

STATENS KUNSTFONDS 2016 ÅRSBERETNING OVERSIGT OVER TILDELINGER TILDELINGER OVERSIGT OVER ALLE TILDELINGER INDHOLD 2 HÆDERSYDELSER 3 OVERSIGT ARKITEKTUR 4 BILLEDKUNST 9 OVER ALLE FILM 47 KUNSTHÅNDVÆRK & DESIGN 50 TILDELINGER LITTERATUR 61 MUSIK 111 I 2016 SCENEKUNST 159 TVÆRGÅENDE UDVALG 183 Note: Oversigten indeholder tildelinger af tilskud, som udvalge- ne har truffet beslutning om i 2016. Nogle af beslutningerne bli- ver bevillingsmæssigt først udmøntet i 2017, og der kan derfor forekomme uoverensstemmelser mellem summerne af de for- skellige tildelinger set i forhold til tilskudsregnskabet i indevæ- rende beretning, idet sidstnævnte udelukkende viser fordelingen af de bevillinger, som udvalgene rådede over i kalenderåret 2016. TILDELINGER TILDELINGER HÆDERSYDELSER 3 Følgende kunstnere er i 2016 tildelt Statens Kunstfonds hædersydelse af repræsentantskabet efter indstilling TILDELINGER fra det relevante legatudvalg i fonden: AF BILLEDKUNST HENRIK OLESEN, billedkunstner HÆDERS- JENS HAANING, billedkunstner KIRSTEN DUFOUR, billedkunstner YDELSER FILM BILLE AUGUST, filminstruktør I 2016 JANNIK HASTRUP, filminstruktør KUNSTHÅNDVÆRK OG DESIGN JAN MACHENHAUER, beklædningsdesigner KAREN BENNICKE, keramiker PER MOLLERUP, designer LITTERATUR HENNING VANGSGAARD, oversætter KATRINE MARIE GULDAGER, forfatter MUSIK IRENE BECKER, komponist JØRGEN EMBORG, komponist STEFFEN BRANDT, sangskriver/komponist HÆDELSEYDELSER TILDELINGER ARKITEKTUR INDHOLD 4 TILDELINGER LEGAT- & PROJEKTSTØTTEUDVALGET OVERSIGT FOR ARKITEKTUR PROJEKTSTØTTE 5 OVER CAN LIS 6 TREÅRIGE -

The Blitz - Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

The Blitz - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Blitz From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia The Blitz (shortened from German 'Blitzkrieg', "lightning war") was the period of sustained strategic bombing of the The Blitz United Kingdom by Nazi Germany during the Second World Part of Second World War, Home Front War. Between 7 September 1940 and 21 May 1941 there were major aerial raids (attacks in which more than 100 tonnes of high explosives were dropped) on 16 British cities. Over a period of 267 days (almost 37 weeks), London was attacked 71 times, Birmingham, Liverpool and Plymouth eight times, Bristol six, Glasgow five, Southampton four, Portsmouth and Hull three, and there was also at least one large raid on another eight cities.[1] This was a result of a rapid escalation starting on 24 August 1940, when night bombers aiming for RAF airfields drifted off course and accidentally destroyed several London homes, killing civilians, combined with the UK Prime Minister Winston Churchill's immediate response The undamaged St Paul's Cathedral surrounded by smoke of bombing Berlin on the following night. and bombed-out buildings in December 1940 in the iconic St Paul's Survives photo Starting on 7 September 1940, London was bombed by the Date 7 September 1940 – 21 May 1941[1][a] [7] Luftwaffe for 57 consecutive nights. More than one (8 months, 1 week and 2 days) million London houses were destroyed or damaged, and more than 40,000 civilians were killed, almost half of them Location United Kingdom in London.[4] Ports and industrial centres outside London Result German strategic failure[3] were also heavily attacked. -

THE LIVERPOOL BLITZ, a PERSONAL EXPERIENCE. by Jim

THE LIVERPOOL BLITZ, A PERSONAL EXPERIENCE. By Jim McKnight INTRODUCTION In 2014 Merseyside Police discovered some photographs that had been police records of bomb damage during World War II. This was reported on BBC “News from the North”. Fortunately, I hit the record button on our TV in time. A few of the photos were flashed on the screen, and suddenly I was amazed to realise that I remembered one particular scene very well. This was because I was there probably about the same time as the photograph was taken. I was seven years old then. That I should remember the scene so vividly seventy four years later is astonishing. Since then, I have verified that I was correct, and I think now is the time to record my memories of the Liverpool Blitzes. THE PORT OF LIVERPOOL It is not always realised that Liverpool was the most heavily bombed area of the country, outside of London, because Merseyside provided the largest port for the war effort. The government was concerned to hide from the Germans just how much damage had been inflicted upon the docks, so reports on the bombing were kept low-key. At one time the dock capacity was halved by bombing, and considering that Merseyside was the main link with America, this put the war effort in jeopardy. Over 90 per cent of imported war materiel came through Merseyside (the rest mainly came through Glasgow). Liverpool housed Western Approaches Command, the naval headquarters for the Battle of the Atlantic. It was responsible for organising the convoys, including The famous waterfront, showing the three Graces in the 1930s The Tunnel Ventilator behind the RH. -

REEVISM Volume I Number I Version 1.4

Contents MARK REEVE – Editorial............................................................................2 MARK REEVE & OTHERS – Collected Esoteric Tips..........................3 MARK REEVE – Scared: An Anagram of Sacred....................................9 MR NIGHTLIGHT – Liverpool Mysteries........................................... 13 MARK REEVE – The Midnight Desires of Wyrd Engines................ 20 MARK REEVE – The Alpha-Omega God Code.................................. 35 MARK REEVE – Grounding Box............................................................ 47 UNKNOWN – Basic Spellcasting ........................................................... 49 UNKNOWN – Reassurance Therapy & the Placebo ......................... 52 JENNY JAMES & MARK REEVE – Atlantis Rising............................. 55 MARK REEVE – The Gazing Globes ..................................................... 64 MARK REEVE – The Lost Goth Bands of Britain .............................. 65 REEVISM Volume I Number I Version 1.4. Published by Spook Press in July 2016. All rights reserved. Copyright © 2013, 2014, 2016 Mark Reeve/the Respective Artist(s). First published in April 2016. Most of this material first appeared in BE4004 (Nobody’s Business, 2013) & Noness (Nobody’s Business, 2014) in slightly different versions. These two publications have been superseded by Reevism. SUPREME COMMANDER .....................................................Mark Reeve ACTIVE MUSE.............................................................................Lucinda Opal PRINTER’S -

Year 6 World War Two Project the Blitz In

Year 6 World War Two Project The Blitz in Liverpool TASK: Use the internet, or books, to find out as much information as you can about the Blitz in Liverpool during World War Two. You might also wish to find out what life was like, particularly for children, during this time. You can choose how to record and present your research findings. 1) Write a factual report 2) Create a fact file with sketches/photos and captions 3) Create your own PowerPoint presentation using text and images 4) Create your own WWII news programme (write a script and ask someone at home to film you on a mobile phone or IPad (use Movie Maker)) 5) Draw a poster (on paper or using a computer or IPad) What should I research? RESEARCH IDEAS You can find out about and present any facts about the Liverpool blitz you wish; however here are some ideas that might help to guide you. You might want to find out: When did the first air raids take place on Liverpool? When was the first major attack? How many bombs were dropped? How many people were killed? On what dates did air raids take place in May 1941? How many people were killed or seriously injured? What was destroyed? In which areas of Liverpool were air raids most concentrated (areas where most raids took place)? Why were these areas targeted? What were the worst affected areas in Liverpool? Why was Liverpool one of the worst hit cities outside of London? How many people were left homeless in Liverpool? Was Huyton attacked during the blitz? Why was Huyton important during WWII? Were children evacuated from -

Working Paper Manchester / Liverpool

Shr ink ing Cit ies -------------------------------------------------------------------------------- MANCHESTER / LIVERPOOL II LIVERPOOL / MANCHESTER ARBEITSMATERIALIEN WORK ING PAPERS PABOCIE MATEPIALY ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ MANCHESTER / LIVERPOOL MANCHESTER / LIVERPOOL II --------------------------------------------- March 2004 -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Shrinking Cities A project initiated by the Kulturstiftung des Bundes (Federal Cultural Foundation, Germany) in cooperation with the Gallery for Contemporary Art Leipzig, Bauhaus Foundation Dessau and the journal Archplus. Office Philipp Oswalt, Eisenacher Str. 74, D-10823 Berlin, P: +49 (0)30 81 82 19-11, F: +49 (0)30 81 82 19-12, II [email protected], www.shrinkingcities.com TABLE OF CONTENTS -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 3INTRODUCTION Philipp Misselwitz 5MAP OF THE M62 REGION 6STATISTICAL DATA: MANCHESTER / LIVERPOOL Ed Ferrari, Anke Hagemann, Peter Lee, Nora Müller and Jonathan Roberts M62 REGION 11 ABANDONMENT AS OPPORTUNITY Katherine Mumford and Anne Power 17 CHANGING HOUSING MARKETS AND URBAN REGENERATION: THE CASE OF THE M62 CORRIDOR Brendan Nevin, Peter Lee, Lisa Goodson, Alan Murie, Jenny Phillimore and Jonathan Roberts 22 CHANGING EMPLOYMENT GEOGRAPHY IN ENGLAND’S NORTH WEST Cecilia Wong, Mark Baker and Nick Gallent MANCHESTER 32 MANCHESTER CITY