[File: D&E Chapter 1]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Short Report

Fifth All India Conference of China Studies Visva-Bharati, Santiniketan, December 15-16, 2012 REPORT Day One: 15 December 2012 Inaugural Session Chair: Professor Sushanta Duttagupta, Vice-Chancellor, Visva Bharati The Inaugural Session of the Fifth All India Conference of China Studies was held in Lipika Auditorium of Visva-Bharati. The session was chaired by Prof. Sushanta Dattagupta, Vice Chancellor of Visva-Bharati University. The dignitaries and participants were welcomed by Dr. Avijit Banerjee, Conference Co-convenor and Head, Cheena Bhavana, Visva-Bharati. Prof. Alka Acharya, Director, Institute of Chinese Studies (ICS), and Prof. Artatrana Nayak, Principal, Bhasa Bhavana, Visva-Bharati, greeted the participants and conveyed their wishes for a successful conference. In the Introductory Remarks, Prof. Monoranjan Mohanty, Chairperson, ICS, spoke about Tagore’s philosophy of the Visva Manava or the Universal Man and underscored Tagore’s vision that a holistic approach to music, science, knowledge and nature would lead the minds to a state of creative unity. He mentioned that Santiniketan was a pilgrimage to China scholars of India. Gurudev Rabindranath Tagore and Prof. Tan Yunshan conceived and built Cheena Bhavana as a repository of India-China civilizational interaction, and it is indeed the birthplace of China Studies in modern India. He hoped that the conference will begin an interactive phase between Cheena Bhavana and ICS, that will strengthen cooperation in the areas of cultural, historical, literary and classical studies. He further 1 stated that today China Studies in India faces new challenges that call for deeper understanding of both history and culture. Therefore, it is appropriate that the focal theme of the conference to be held here in Visva Bharati is history, historiography and reinterpreting history, as this was the mission of Tagore and Tan Yun-shan. -

Tagore: His Educational Theory and Practice and Its Impact on Indian Education

TAGORE—HIS EDUCATIONAL THEORY AND PRACTICE AND ITS IMPACT ON INDIAN EDUCATION By RADHA VINOD JALAN A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE COUNCIL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 1976 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The completion of this study would not have been possible without the help and support of a number of in- dividuals. The writer wishes to express her sincere appreciation to her chairman. Dr. Hal G. Lewis, for his interest. in and understanding guidance through all phases of this study until its completion. The assistance of the other members of her committee was invaluable, and appreciation is expressed to Dr. Austin B. Creel and Dr. Vynce A. Hines. Appreciation is also expressed to Mrs. Voncile Sanders for her expert typing of the final copy. The writer is grateful to her husband Vinod, and our daughter, for their sacrifice, devotion, and inspiration. TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ABSTRACT CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION 1 II RELATED EDUCATIONAL READINGS. 7 Tagore's Selected Writings on Education ........... 8 Some Significant Works on Tagore 19 Notes 29 Ill THE EDUCATIONAL THEORY OF TAGORE. 31 Background for Tagore ' s Theory . 31 Characteristics of Indian Education During Tagore's Time . 31 Tagore's Childhood Ex- periences Regarding Education. 36 Aims of Education 39 Summary. 46 Ideal Education. ... 46 Summary 52 Congruency Between Education and Society 53 Notes 59 IV PRACTICAL ASPECTS OF TAGORE'S THEORY. 60 TABLE OF CONTENTS (Continued) Page Origin and Development of the Institution 50 Main Divisions of the Institution 57 Patha-Bhavana (The School). -

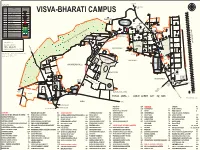

Updated Campus Map in PDF Format

KOPAI RIVER N NE LEGEND : NW E PRANTIK STATION W 1.5 KM SL. NO. NAME SYMBOL SE WS 1. HERITAGE BUILDING S 2. ADMIN. BUILDING VISVA-BHARATI CAMPUS 3. ACADEMIC BUILDING 42 4. GUEST HOUSE G 5. AUDITORIUM / HALL 101 6. HOSTEL BUILDING DEER PARK 44 7. CANTEEN C G RATAN PALLI 8. HOSPITAL LAL BANDH 01 41 SHYAMBATI 43 40 9. WATER BODY G 39 KALOR DOKAN 10. SWIMMING POOL 45 11. PLAY GROUND 38 93 91 90 UTTARAYANA/ 48 12. AGRICULTURE FARM RABINDRA BHAVANA 34 OLD MELA GROUND 94 POND (JAGADISH KANAN) 37 35 02 13. VILLAGE 33 47 T 98 92 46 G C T A T 14. WILDLIFE SANCTUARY 96 89 52 53 54 36 PM HOSPI AL 97 SIKSHA BHAVANA COMPLEX 50 51 04 E S A U R Y 100 03 15. ROAD 58 55 G SEVA PALLI 32 99 95 31 G 16. V.B.PROPERTY LINE D L F N PRATI ICH SRIPALLI SANGIT 60 KALA BHAVANA 57 LIPIKA I L I BHAVANA 56 30 N R LW E KALIGUNJE PEARSON PALLI 49 59 AMRAKUNJA 141 66 61 64 63 C 29 65 27 28 76 77 62 PATHA BHAVANA AREA NT LCERA L A 74 AY 68 75 LI RBR 103 67 EASTER AILIN AY PREPARED BY:- B A L V P U R W 25 78 102 F E PURVA PALLI C CENTRAL O FIC POUS MELA GROUND ESTATE OFFICE, SU 3 79 ASRAMA 80 26 73 81 RI 0 KM PLAY GROUND 24 VISVA - BHARATI 69 23 05 SIMANTAPALLI 83 22 SANTINIKETAN, PIN-731235 72 88 82 PLAY HATIPUKUR GROUND 85 84 SBI AUROSRI MARKET 21 86 71 LEGAL DISCLAIMER : THIS IS AN INDICATIVE MAP ONLY, 20 HATIPUKUR 70 16 FOR THE AID OF GENERAL PUBLIC. -

Annual Report 17-18 Full Chap Final Tracing.Pmd

VISVA-BHARATI Annual Report 2017-2018 Santiniketan 2018 YATRA VISVAM BHAVATYEKANIDAM (Where the World makes its home in a single nest) “ Visva-Bharati represents India where she has her wealth of mind which is for all. Visva-Bharati acknowledges India's obligation to offer to others the hospitality of her best culture and India's right to accept from others their best ” -Rabindranath Tagore Dee®ee³e& MeebefleefveJesÀleve - 731235 Þeer vejsbê ceesoer efkeMkeYeejleer SANTINIKETAN - 731235 efpe.keerjYetce, heefM®ece yebieeue, Yeejle ACHARYA (CHANCELLOR) VISVA-BHARATI DIST. BIRBHUM, WEST BENGAL, INDIA SHRI NARENDRA MODI (Established by the Parliament of India under heÀesve Tel: +91-3463-262 451/261 531 Visva-Bharati Act XXIX of 1951 hewÀJeÌme Fax: +91-3463-262 672 Ghee®ee³e& Vide Notification No. : 40-5/50 G.3 Dt. 14 May, 1951) F&-cesue E-mail : [email protected] Òees. meyegpeJeÀefue mesve Website: www.visva-bharati.ac.in UPACHARYA (VICE-CHANCELLOR) (Offig.) mebmLeeheJeÀ PROF. SABUJKOLI SEN jkeervêveeLe þeJegÀj FOUNDED BY RABINDRANATH TAGORE FOREWORD meb./No._________________ efoveebJeÀ/Date._________________ For Rabindranath Tagore, the University was the most vibrant part of a nation’s cultural and educational life. In his desire to fashion a holistic self that was culturally, ecologically and ethically enriched, he saw Visva-Bharati as a utopia of the cross cultural encounter. During the course of the last year, the Visva-Bharati fraternity has been relentlessly pursuing this dream. The recent convocation, where the Chancellor Shri Narendra Modi graced the occasion has energized the Univer- sity community, especially because this was the Acharya’s visit after 10 years. -

The Plea for Asia—Tan Yunshan, Pan-Asianism and Sino-Indian Relations

The Plea for Asia 353 The Plea for Asia—Tan Yunshan, Pan-Asianism and Sino-Indian Relations Brian Tsui In 1927, the Buddhist scholar, Tan Yunshan, travelled to Santiniketan on the invitation of Rabindranath Tagore to teach Chinese at Visva Bharati University. Subsequent years would see him develop close ties with the Guomindang and Congress leaders, secure Chinese state funding for the fi rst sinological institute in India and mediate between the nationalist movements during the Second World War. That a relatively marginal academic, who participated in neither the May Fourth Movement nor any major political party, and who had little prior experience of India, could have played such an important role in twentieth century Sino-Indian relations raises questions over the conditions that made possible Tan’s illustrious career. This article argues that Tan’s success as an institution builder and diplomatic intermediary was attributable to his ideological affi nity with the increasing disillusionment with capitalist modernity in both China and India, the shifting dynamics of the Pan-Asianist movement and the conservative turn of China’s nationalist movement after its split with the communists in 1927. While Nationalist China and the Congress both tapped into the civilizational discourse that was supposed to bind the two societies together, the idealism Tan embodied was unable to withstand the confl ict of priorities between nation- states in the emerging Cold War order. The academic Tan Yunshan (1898–1983) played a pivotal role in Sino-Indian relations before the advent of the Indian nation-state. As an individual, Tan might have preferred that his efforts focused on promoting educational ties between the two countries. -

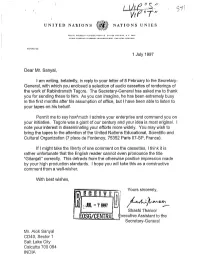

M R // Vvt/ Ffi*R~F~'R 7 F UNITED Natiions ||W NATIONS UNIES

M r // VVt/ ffi*R~f~'r 7 f UNITED NATiIONS ||W NATIONS UNIES s. N.V. loot? REFERENCE: 1 July 1997 Dear Mr. Sanyal, I am writing, belatedly, in reply to your letter of 8 February to the Secretary- General, with which you enclosed a selection of audio cassettes of renderings of the work of Rabindranath Tagore. The Secretary-General has asked me to thank you for sending these to him. As you can imagine, he has been extremely busy in the first months after his assumption of office, but I have been able to listen to your tapes on his behalf. Permit me to say how'much I admire your enterprise and commend you on your initiative. Tagore was a giant of our century and your idea is most original. I note your interest in disseminating your efforts more widely. You may wish to bring the tapes to the attention of the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (7 place de Fontenoy, 75352 Paris 07-SP, France). If I might take the liberty of one comment on the cassettes, I think it is rather unfortunate that the English reader cannot even pronounce the title "Gitanjali" correctly. This detracts from the otherwise positive impression made by your high production standards. I hope you will take this as a constructive comment from a well-wisher. With best wishes, Yours sincerely, Shashi Tharoor xecutive Assistant to the Secretary-General Mr. Alok Sanyal CD40, Sector 1 Salt Lake City Calcutta 700 064 INDIA M1BHH Alok Sanyal ph. D. Mailing Address : Department of Physics, Jadavpur University CD 40, SECTOR I SALT LAKE CITY W] CALCUTTA-700064 INDIA Telephone +91 33 337 5037/337 59U8 +91 33 U40 8656 UNITED N-ew Y*vK MY 10017 Indian poets especially the Bengali poet Rabindranath Tagore lead the list of Asian writers who'have been most translated into the languages of the world. -

A New Day for China-India Relations

The Development of Road Ahead: Building China-India relations in New Relations Recent 70 Years Vol.20 No.2 | March - April 2020 A New Day for China-India Relations 国内零售价:10 元 / India 100 www.chinaindiadialogue.com 可绕地球赤道栽种树木按已达塞罕坝机械林场的森林覆盖率寒来暑往,沙地变林海,荒原成绿洲。半个多世纪,三代人耕耘。牢记使命 80% , 1 米株距排开, 艰苦创业 12 圈。 绿色发展 Saihanba is a cold alpine area in northern Hebei Province bordering the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region. It was once a barren land but is now home to 75,000 hectares of forest, thanks to the efforts make by generations of forestry workers in the past 55 years. Every year the forest purifies 137 million cubic meters of water and absorbs 747,000 tons of carbon dioxide. The forest produces 12 billion yuan (around US$1.8 billion) of ecological value annually, according to the Chinese Academy of Forestry. 可绕地球赤道栽种树木按已达塞罕坝机械林场的森林覆盖率寒来暑往,沙地变林海,荒原成绿洲。半个多世纪,三代人耕耘。牢记使命 CHINA-INDIA DIALOGUE CONTENTS ADMINISTRATIVE AGENCY: 主管: China International 中国外文出版发行事业局 (中国国际出版集团) 80% Publishing Group CHINDIA NEWS PUBLISHER: 主办、出版: China Pictorial 人民画报社 Memorabilia of 70th Anniversary of the Establishment of ADDRESS: 地址: , 33 Chegongzhuang Xilu, Haidian, 北京市海淀区 Beijing 100048, China 车公庄西路33号 Diplomatic Relations between China and India / p.02 1 米株距排开, 艰苦创业 PRESIDENT: Yu Tao 社长:于涛 12 EDITORIAL BOARD: 编委会: 圈。 OPENING ESSAY Yu Tao, Li Xia, 于 涛 、李 霞 、 He Peng, Bao Linfu, 贺 鹏 、鲍 林 富 、 Yu Jia, Yan Ying 于 佳 、闫 颖 CHARTING A NEW COURSE FOR EDITOR-IN-CHIEF: Li Xia 总编辑:李霞 EDITORIAL DIRECTORS: 编辑部主任: DRAGON-ELEPHANT TANGO 08 Qiao Zhenqi, Yin Xing 乔振祺、殷星 PERATIONS IRECTOR -

Tagore's Asian Voyages

THE NALANDA-SRIWIJAYA CENTRE, Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, Singapore, commemorates the 150th anniversary of World Poet Rabindranath Tagore Tagore’s Asian Voyages SELECTED SPEECHES AND WRITINGS ON RABINDRANATH TAGORE Nalanda-Sriwijaya Centre Logo in Full Color PROCESS COLOR : 30 Cyan l 90 Magenta l 90 Yellow l 20 Black PROCESS COLOR : 40 Cyan l 75 Magenta l 65 Yellow l 45 Black PROCESS COLOR : 50 Cyan l 100 Yellow PROCESS COLOR : 30 Cyan l 30 Magenta l 70 Yellow l 20 Black PROCESS COLOR : 70 Black PROCESS COLOR : 70 Cyan l 20 Yellow The Nalanda-Sriwijaya Centre at the Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, Singapore, pursues research on historical interactions among Asian societies and civilisations. It serves as a forum for comprehensive study of the ways in which Asian polities and societies have interacted over time through religious, cultural, and economic exchanges and diasporic networks. The Centre also offers innovative strategies for examining the manifestations of hybridity, convergence and mutual learning in a globalising Asia. http://nsc.iseas.edu.sg/ 1 CONTENTS 3 Preface Tansen Sen 4 Tagore’s Travel Itinerary in Southeast Asia 8 Tagore in China 10 Rabindranath Tagore and Asian Universalism Sugata Bose 19 Rabindranath Tagore’s Vision of India and China: A 21st Century Perspective Nirupama Rao 24 Realising Tagore’s Dream For Good Relations between India and China George Yeo 26 A Jilted City, Nobel Laureates and a Surge of Memories – All in One Tagorean Day Asad-ul Iqbal Latif 28 Tagore bust in Singapore – Unveiling Ceremony 30 Centenary Celebration Message Lee Kuan Yew 31 Messages 32 NSC Publications Compiled and designed by Rinkoo Bhowmik Editorial support: Joyce Iris Zaide 1 Nalanda-Sriwijaya Centre Projects Research Projects Lecture Series The Nalanda-Sriwijaya Centre The Nalanda-Sriwijaya Centre hosts pursues a range of research projects three lecture series focusing on intra- Asian interactions: The Nalanda-Sriwijaya within the following areas: 6. -

Tan Chung Institute of Chinese Studies, India

HIMALAYA CALLING The Origins of and U020hc_9781938134593_tp.indd 1 5/2/15 5:14 pm May 2, 2013 14:6 BC: 8831 - Probability and Statistical Theory PST˙ws This page intentionally left blank HIMALAYA CALLING The Origins of and Tan Chung Institute of Chinese Studies, India World Century U020hc_9781938134593_tp.indd 2 5/2/15 5:14 pm Published by World Century Publishing Corporation 27 Warren Street, Suite 401-402, Hackensack, NJ 07601 British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. HIMALAYA CALLING The Origins of China and India Copyright © 2015 by World Century Publishing Corporation All rights reserved. This book, or parts thereof, may not be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or any information storage and retrieval system now known or to be invented, without written permission from the publisher. For photocopying of material in this volume, please pay a copying fee through the Copyright Clearance Center, Inc., 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, USA. In this case permission to photocopy is not required from the publisher. ISBN 978-1-938134-59-3 In-house Editor: Sandhya Venkatesh Typeset by Stallion Press Email: [email protected] Printed in Singapore Sandhya - Himalaya Calling.indd 1 18/3/2015 4:57:45 PM 9”x 6” b1937 Himalaya Calling: The Origins of China and India Dedicated to Ji Xianlin ᆓ㗑᷇ (1911–2009) Eternal Camaraderie in Chindia b1937_FM.indd v 3/10/2015 1:42:21 PM May 2, 2013 14:6 BC: 8831 - Probability and Statistical Theory PST˙ws This page intentionally left blank 9”x 6” b1937 Himalaya Calling: The Origins of China and India FOREWORD It is the historian’s constant endeavour to prevent the present from colour- ing our view of the past, but not vice versa. -

The Limits of Jawaharlal Nehru's Asian Internationalism and Sino-Indian Relations, 1949-1959" (2015)

Salem State University Digital Commons at Salem State University Graduate Theses Student Scholarship 2015 The Limits of Jawaharlal Nehru's Asian Internationalism and Sino- Indian Relations, 1949-1959 Rosie Tan Segil Salem State University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.salemstate.edu/graduate_theses Part of the Asian History Commons, Diplomatic History Commons, and the Political History Commons Recommended Citation Segil, Rosie Tan, "The Limits of Jawaharlal Nehru's Asian Internationalism and Sino-Indian Relations, 1949-1959" (2015). Graduate Theses. 14. https://digitalcommons.salemstate.edu/graduate_theses/14 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at Digital Commons at Salem State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons at Salem State University. THE LIMITS OF JAWAHARLAL NEHRU'S ASIAN INTERNATIONALISM Rosie Tan Segil Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS IN HISTORY from SALEM STATE ITIVIVERSITY THE GRADUATE SCHOOL May 2015 Table of Contents INTRODUCTION.................................................................... 1 - 7 CHAPTER 1 — Panchsheel........................................................ 8 - 36 CHAPTER 2 —The 1955 Asian-African Conference in Bandung.......... 37 - 53 CONCLUSION .................................................................... 54 - 55 BIBLIOGRAPHY..................................................................56 - 62 APPENDIX I — Sino-Indian Border Disputes...................................63 iv Introduction "Asiafascinates me, the long past ofAsia, the achievements ofAsia though millennia ofhistory, the troubled p~^esent o,f'Asia and the futut~e that is taking shape almost before our eyes."' - Jawaharlal Nehn► Long before Jawaharlal Nehru became India's first prime minister, he held a long fascination with Asian unity in which China and India would play a central role. -

Chinese Teaching to Indian Students

Journal of Technology and Chinese Language Teaching Volume 4 Number 1, June 2013 http://www.tclt.us/journal/2013v4n1/kochhar.pdf pp. 14-36 Teaching Chinese to Indian Students: An Understanding (教印度学生学汉语:一些认识) Geeta Kochhar (康婧) Jawaharlal Nehru University (尼赫鲁大学) [email protected] Abstract: The paper highlights the difficulties of learning Chinese language for Indian students with diverse linguistic backgrounds, while reemphasizing the point that Chinese language in itself is one of the toughest languages, especially in India where it has to be learned through another foreign language i.e. English. The paper hypothesizes that multilingual speakers of any community faces greater problems of learning new languages when the medium of teaching is not their mother tongue and when there is lack of target language environment with proper infrastructure. The study is based on a questionnaire circulated among 79 students between the age group of 18 to 30 learning Chinese as a major. Respondents belong to various regional and linguistic backgrounds, but residing and learning Chinese in Delhi. In addition, speech recording analysis and answer scripts analysis is done to identify practical problems faced by the students of Jawaharlal Nehru University. The study excludes those who acquired the language more than three years ago. 摘要:印度学生虽然有多种语言的背景,可是学汉语的时候有不少困 难。汉语本身就是难以掌握的语言,不过,对印度学生来说,通过一 个外语,即英语,掌握汉语是最大的难点。本论文认为,会说多种语 言的群体如果不用母语来学外语而且也没有目的语言的环境,就难以 掌握外语。本论文用尼赫鲁大学 79 个学生的实际考察来作分析。结果 发现间接方法来教汉语是学生掌握不了汉语的最大原因。印度大学的 汉语教材陈旧,当地教师的缺乏,以及缺少当地语言环境是其他的困 境。先进技术的使用可以消除一些困难。 Keywords: Indian students, Chinese language learning, non-native language and multilingual environment, learning difficulties 关键词:印度学生,汉语学习,非母语多语言环境,学习难点 © 2013 The Author. Compilation © 2013. Journal of Technology and Chinese Language Teaching 14 Geeta Kochhar Teaching Chinese to Indian Students: An Understanding 1. -

Estimates Committee ( 1 9 6 4 - 6 5 )

B .C . N o. 4x 4 ESTIMATES COMMITTEE ( 1 9 6 4 - 6 5 ) EIGHTY -THIRD REPORT (THIRD LOK SABHA') MINISTRY OF EDUCATION VISVA-BHARATI UNIVERSITY I. OK SABHA SECRETARIAT N EW D E L H I AxtriU 1965 VaimaMha, 1&87 (SaMa) P rice : Rs. X * xo Pais* LIST OF AUTHORISED AGENTS FOR THE SALE OF LOK SABHA SECRETARIAT PUBLICATIONS SI. Name of Agent Agency Si. Name of Agent Agency No* No. No. No. ANDHRA PRADESH 11. Charles Lambert and Company, io i, Mahatma i. Andhra University Gene Gandhi Road, ral Cooperative Stores Opp. Clock Tower, Ltd., Waltair (Visakha- Fort, Bombay . 30 patnam) . 8 12. The Current Book House, 2. G. R. Lakshmipathy Maruti Lane, Raghu- Chetty & Sons, General nath Dadaji Street, Merchants & News Bombay-i . 60 Agents, Newpet, Chandragiri, Chittoor 13. Deccan Book Stall, Fergu District . 94 son College Road, Poona-4 . 65 ASSAM RAJASTHAN 3. Western Book Depot, Pan 14. Information Centre, Bazar, Gauhati. 7 Govt, of Rajasthan, Tripolia, Jaipur City. 38 BIHAR UTTAR PRADESH 4. Amar Kitab Ghar, Post i$. Swastik Industrial Works, Box 78, Diagonal Road, <>9, Holi Street, Meerut Jamshedpur. 37 City . * 16. Law Book Company, GUJARAT Sardar Patel Marg, Allahabad-1 48 j. Vijay Stores, Station Road, Anand* . 35 WEST BENGAL 6. The New Order Book 17. Granthaloka, 5/1, Ambica Company, Ellis Bridge, Mookherjee Road, Ahmedabad-6. 63 Belgharia, 24 Paragnas. 10 MADHYA PRADESH 18. W. Newman & Company Limited, 3, Old Court House Street, Calcutta. 44 7. Modem Book House, Shiv Vilas Palace, Indore city. 19. Firma K. L. Mukho- 13 padhyay, 6/1A, Ban- chharam Akrur Lane, Calcutta-12 82 MAHARASHTRA 8.