Tagore: His Educational Theory and Practice and Its Impact on Indian Education

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

IP Tagore Issue

Vol 24 No. 2/2010 ISSN 0970 5074 IndiaVOL 24 NO. 2/2010 Perspectives Six zoomorphic forms in a line, exhibited in Paris, 1930 Editor Navdeep Suri Guest Editor Udaya Narayana Singh Director, Rabindra Bhavana, Visva-Bharati Assistant Editor Neelu Rohra India Perspectives is published in Arabic, Bahasa Indonesia, Bengali, English, French, German, Hindi, Italian, Pashto, Persian, Portuguese, Russian, Sinhala, Spanish, Tamil and Urdu. Views expressed in the articles are those of the contributors and not necessarily of India Perspectives. All original articles, other than reprints published in India Perspectives, may be freely reproduced with acknowledgement. Editorial contributions and letters should be addressed to the Editor, India Perspectives, 140 ‘A’ Wing, Shastri Bhawan, New Delhi-110001. Telephones: +91-11-23389471, 23388873, Fax: +91-11-23385549 E-mail: [email protected], Website: http://www.meaindia.nic.in For obtaining a copy of India Perspectives, please contact the Indian Diplomatic Mission in your country. This edition is published for the Ministry of External Affairs, New Delhi by Navdeep Suri, Joint Secretary, Public Diplomacy Division. Designed and printed by Ajanta Offset & Packagings Ltd., Delhi-110052. (1861-1941) Editorial In this Special Issue we pay tribute to one of India’s greatest sons As a philosopher, Tagore sought to balance his passion for – Rabindranath Tagore. As the world gets ready to celebrate India’s freedom struggle with his belief in universal humanism the 150th year of Tagore, India Perspectives takes the lead in and his apprehensions about the excesses of nationalism. He putting together a collection of essays that will give our readers could relinquish his knighthood to protest against the barbarism a unique insight into the myriad facets of this truly remarkable of the Jallianwala Bagh massacre in Amritsar in 1919. -

DATE of ENTRANCE PD, UG, Cert., Dip, ADV 2018

VISVA-BHARATI Information relating to Admission to Pre-Degree, UG, Certificate, Diploma & Advanced Diploma Courses PRE- DEGREE (CLASS XI ) (ADMISSION WILL BE MADE ON MERIT BASIS) TENTATIVE DATE TENTATIVE DATE Sl. COURSE BHAVANA COURSE NAME FOR PUBLICATION OF ONLINE TIME VENUE No. TYPE OF MERIT LIST ADMISSION 1 Patha Bhavana Pre-Degree Humanities 2 Patha Bhavana Pre-Degree Science (Online Admission Process will be notified shortly after publication of the merit 25/06/2018 3 Siksha Satra Pre-Degree Humanities list ) 4 Siksha Satra Pre-Degree Science UG COURSES (ADMISSION STRICTLY ON MERIT BASIS) TENTATIVE DATE TENTATIVE DATE Sl. COURSE BHAVANA COURSE NAME FOR PUBLICATION OF TIME VENUE No. TYPE OF MERIT LIST ONLINE ADMISSION 1 UG B.A - Japanese(Hons) 2 UG B.A - BENGALI B.A - Chinese (Prep) 3 UG FOLLOWED BY HONS. 4 UG B.A - ENGLISH B.A - EUROPEAN 5 UG STUDIES 6 UG B.A - HINDI Bhasha Bhavana, B.A - INDO- TIBETIAN (Online Admission Process will be notified shortly after publication 7Visva-Bharati, UG 25/06/2018 (hons) of the merit list ) Santiniketan B.A - INDO- 8 UG TIBETIAN(Prep.) Followed by Hons B.A - Japanese (Prep.) 9 UG followed by Honours. 10 UG B.A - PERSIAN (HONS) B.A - PERSIAN(Prep.) 11 UG followed by Hons 12 UG B.A - SANSKRIT B.A - ANCIENT INDIAN 13 UG HISTORY, CULTURE & ARCHAEOLOGY B.A - COMPARATIVE 14Vidya Bhavana, UG Visva-Bharati, RELIGION 15Santiniketan UG B.A - ECONOMICS 16 UG B.A - GEOGRAPHY 17 UG B.A - HISTORY 18 UG B.A - PHILOSOPHY 19 UG B.Sc - BOTANY 20 UG B.Sc - CHEMISTRY (Online Admission Process will be notified shortly after publication B.Sc - COMPUTER 25/06/2018 21Siksha Bhavana, UG SCIENCE of the merit list ) Visva-Bharati, 22 UG B.Sc - MATHEMETICS Santiniketan 23 UG B.Sc - PHYSICS 24 UG B.Sc - STATISTICS 25 UG B.Sc - ZOOLOGY Palli Siksha 26 Bhavana, Visva- UG B.Sc. -

Short Report

Fifth All India Conference of China Studies Visva-Bharati, Santiniketan, December 15-16, 2012 REPORT Day One: 15 December 2012 Inaugural Session Chair: Professor Sushanta Duttagupta, Vice-Chancellor, Visva Bharati The Inaugural Session of the Fifth All India Conference of China Studies was held in Lipika Auditorium of Visva-Bharati. The session was chaired by Prof. Sushanta Dattagupta, Vice Chancellor of Visva-Bharati University. The dignitaries and participants were welcomed by Dr. Avijit Banerjee, Conference Co-convenor and Head, Cheena Bhavana, Visva-Bharati. Prof. Alka Acharya, Director, Institute of Chinese Studies (ICS), and Prof. Artatrana Nayak, Principal, Bhasa Bhavana, Visva-Bharati, greeted the participants and conveyed their wishes for a successful conference. In the Introductory Remarks, Prof. Monoranjan Mohanty, Chairperson, ICS, spoke about Tagore’s philosophy of the Visva Manava or the Universal Man and underscored Tagore’s vision that a holistic approach to music, science, knowledge and nature would lead the minds to a state of creative unity. He mentioned that Santiniketan was a pilgrimage to China scholars of India. Gurudev Rabindranath Tagore and Prof. Tan Yunshan conceived and built Cheena Bhavana as a repository of India-China civilizational interaction, and it is indeed the birthplace of China Studies in modern India. He hoped that the conference will begin an interactive phase between Cheena Bhavana and ICS, that will strengthen cooperation in the areas of cultural, historical, literary and classical studies. He further 1 stated that today China Studies in India faces new challenges that call for deeper understanding of both history and culture. Therefore, it is appropriate that the focal theme of the conference to be held here in Visva Bharati is history, historiography and reinterpreting history, as this was the mission of Tagore and Tan Yun-shan. -

Tagore's Visva-Bharati: an Inclusive Society

© 2018 IJRAR August 2018, Volume 5, Issue 3 www.ijrar.org (E-ISSN 2348-1269, P- ISSN 2349-5138) Tagore’s Visva-Bharati: An Inclusive Society 1Subhajit Jana, 2Dr. Tarini Halder, 3Golam Ahammad 1B.Ed. Trainee, 2Assistant Professor, 3Assistant Professor 1Department of Education 1University of Kalyani, Kalyani, West Bengal, India Abstract: The myriad personality, the poet, novelist and educationist Rabindranath Tagore innovated an international institution by the name Visva-Bharati which is a hundred miles away from north Kolkata at Santiniketan on December 1921 that is influenced by his life philosophy, social philosophy and educational philosophy. The purpose of the study is to define the objectives and various features of Visva-Bharati that established it as an inclusive society. The study was conducted based on the documents review and the entire analysis drawn on the basis of qualitative data. The main objective of Visva-Bharati is to follow the humanity and universal brotherhood which is far from any kind of religious, caste, lingual, ethnic, cultural, demographic discrimination. Visva-Bharati is an educational institution, but it is a different one, where students are taught in the peaceful and open air, where natural, secular and seasonal ceremonies, festivals and fairs are celebrated instead of religious, ethnic rituals and festivals, and where the wider concepts of internationalism, humanism and universal brotherhood are rooted in philosophy of Tagore that ‘the whole world can find in a single nest.’ Finally, the researchers concluded that the Visva-Bharati is a miniature of inclusive society of world for its inclusive nature of various knowledge; culture of East and West; man, women and natural living and non-living beings; various religious, lingual, castes, creeds, provinces, and classes’ people; and villagers and cities’ people. -

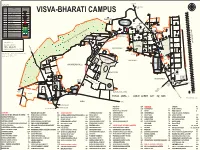

Updated Campus Map in PDF Format

KOPAI RIVER N NE LEGEND : NW E PRANTIK STATION W 1.5 KM SL. NO. NAME SYMBOL SE WS 1. HERITAGE BUILDING S 2. ADMIN. BUILDING VISVA-BHARATI CAMPUS 3. ACADEMIC BUILDING 42 4. GUEST HOUSE G 5. AUDITORIUM / HALL 101 6. HOSTEL BUILDING DEER PARK 44 7. CANTEEN C G RATAN PALLI 8. HOSPITAL LAL BANDH 01 41 SHYAMBATI 43 40 9. WATER BODY G 39 KALOR DOKAN 10. SWIMMING POOL 45 11. PLAY GROUND 38 93 91 90 UTTARAYANA/ 48 12. AGRICULTURE FARM RABINDRA BHAVANA 34 OLD MELA GROUND 94 POND (JAGADISH KANAN) 37 35 02 13. VILLAGE 33 47 T 98 92 46 G C T A T 14. WILDLIFE SANCTUARY 96 89 52 53 54 36 PM HOSPI AL 97 SIKSHA BHAVANA COMPLEX 50 51 04 E S A U R Y 100 03 15. ROAD 58 55 G SEVA PALLI 32 99 95 31 G 16. V.B.PROPERTY LINE D L F N PRATI ICH SRIPALLI SANGIT 60 KALA BHAVANA 57 LIPIKA I L I BHAVANA 56 30 N R LW E KALIGUNJE PEARSON PALLI 49 59 AMRAKUNJA 141 66 61 64 63 C 29 65 27 28 76 77 62 PATHA BHAVANA AREA NT LCERA L A 74 AY 68 75 LI RBR 103 67 EASTER AILIN AY PREPARED BY:- B A L V P U R W 25 78 102 F E PURVA PALLI C CENTRAL O FIC POUS MELA GROUND ESTATE OFFICE, SU 3 79 ASRAMA 80 26 73 81 RI 0 KM PLAY GROUND 24 VISVA - BHARATI 69 23 05 SIMANTAPALLI 83 22 SANTINIKETAN, PIN-731235 72 88 82 PLAY HATIPUKUR GROUND 85 84 SBI AUROSRI MARKET 21 86 71 LEGAL DISCLAIMER : THIS IS AN INDICATIVE MAP ONLY, 20 HATIPUKUR 70 16 FOR THE AID OF GENERAL PUBLIC. -

Annual Report 17-18 Full Chap Final Tracing.Pmd

VISVA-BHARATI Annual Report 2017-2018 Santiniketan 2018 YATRA VISVAM BHAVATYEKANIDAM (Where the World makes its home in a single nest) “ Visva-Bharati represents India where she has her wealth of mind which is for all. Visva-Bharati acknowledges India's obligation to offer to others the hospitality of her best culture and India's right to accept from others their best ” -Rabindranath Tagore Dee®ee³e& MeebefleefveJesÀleve - 731235 Þeer vejsbê ceesoer efkeMkeYeejleer SANTINIKETAN - 731235 efpe.keerjYetce, heefM®ece yebieeue, Yeejle ACHARYA (CHANCELLOR) VISVA-BHARATI DIST. BIRBHUM, WEST BENGAL, INDIA SHRI NARENDRA MODI (Established by the Parliament of India under heÀesve Tel: +91-3463-262 451/261 531 Visva-Bharati Act XXIX of 1951 hewÀJeÌme Fax: +91-3463-262 672 Ghee®ee³e& Vide Notification No. : 40-5/50 G.3 Dt. 14 May, 1951) F&-cesue E-mail : [email protected] Òees. meyegpeJeÀefue mesve Website: www.visva-bharati.ac.in UPACHARYA (VICE-CHANCELLOR) (Offig.) mebmLeeheJeÀ PROF. SABUJKOLI SEN jkeervêveeLe þeJegÀj FOUNDED BY RABINDRANATH TAGORE FOREWORD meb./No._________________ efoveebJeÀ/Date._________________ For Rabindranath Tagore, the University was the most vibrant part of a nation’s cultural and educational life. In his desire to fashion a holistic self that was culturally, ecologically and ethically enriched, he saw Visva-Bharati as a utopia of the cross cultural encounter. During the course of the last year, the Visva-Bharati fraternity has been relentlessly pursuing this dream. The recent convocation, where the Chancellor Shri Narendra Modi graced the occasion has energized the Univer- sity community, especially because this was the Acharya’s visit after 10 years. -

The Plea for Asia—Tan Yunshan, Pan-Asianism and Sino-Indian Relations

The Plea for Asia 353 The Plea for Asia—Tan Yunshan, Pan-Asianism and Sino-Indian Relations Brian Tsui In 1927, the Buddhist scholar, Tan Yunshan, travelled to Santiniketan on the invitation of Rabindranath Tagore to teach Chinese at Visva Bharati University. Subsequent years would see him develop close ties with the Guomindang and Congress leaders, secure Chinese state funding for the fi rst sinological institute in India and mediate between the nationalist movements during the Second World War. That a relatively marginal academic, who participated in neither the May Fourth Movement nor any major political party, and who had little prior experience of India, could have played such an important role in twentieth century Sino-Indian relations raises questions over the conditions that made possible Tan’s illustrious career. This article argues that Tan’s success as an institution builder and diplomatic intermediary was attributable to his ideological affi nity with the increasing disillusionment with capitalist modernity in both China and India, the shifting dynamics of the Pan-Asianist movement and the conservative turn of China’s nationalist movement after its split with the communists in 1927. While Nationalist China and the Congress both tapped into the civilizational discourse that was supposed to bind the two societies together, the idealism Tan embodied was unable to withstand the confl ict of priorities between nation- states in the emerging Cold War order. The academic Tan Yunshan (1898–1983) played a pivotal role in Sino-Indian relations before the advent of the Indian nation-state. As an individual, Tan might have preferred that his efforts focused on promoting educational ties between the two countries. -

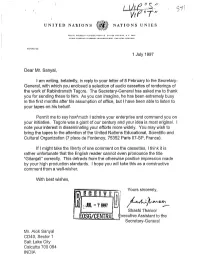

M R // Vvt/ Ffi*R~F~'R 7 F UNITED Natiions ||W NATIONS UNIES

M r // VVt/ ffi*R~f~'r 7 f UNITED NATiIONS ||W NATIONS UNIES s. N.V. loot? REFERENCE: 1 July 1997 Dear Mr. Sanyal, I am writing, belatedly, in reply to your letter of 8 February to the Secretary- General, with which you enclosed a selection of audio cassettes of renderings of the work of Rabindranath Tagore. The Secretary-General has asked me to thank you for sending these to him. As you can imagine, he has been extremely busy in the first months after his assumption of office, but I have been able to listen to your tapes on his behalf. Permit me to say how'much I admire your enterprise and commend you on your initiative. Tagore was a giant of our century and your idea is most original. I note your interest in disseminating your efforts more widely. You may wish to bring the tapes to the attention of the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (7 place de Fontenoy, 75352 Paris 07-SP, France). If I might take the liberty of one comment on the cassettes, I think it is rather unfortunate that the English reader cannot even pronounce the title "Gitanjali" correctly. This detracts from the otherwise positive impression made by your high production standards. I hope you will take this as a constructive comment from a well-wisher. With best wishes, Yours sincerely, Shashi Tharoor xecutive Assistant to the Secretary-General Mr. Alok Sanyal CD40, Sector 1 Salt Lake City Calcutta 700 064 INDIA M1BHH Alok Sanyal ph. D. Mailing Address : Department of Physics, Jadavpur University CD 40, SECTOR I SALT LAKE CITY W] CALCUTTA-700064 INDIA Telephone +91 33 337 5037/337 59U8 +91 33 U40 8656 UNITED N-ew Y*vK MY 10017 Indian poets especially the Bengali poet Rabindranath Tagore lead the list of Asian writers who'have been most translated into the languages of the world. -

A New Day for China-India Relations

The Development of Road Ahead: Building China-India relations in New Relations Recent 70 Years Vol.20 No.2 | March - April 2020 A New Day for China-India Relations 国内零售价:10 元 / India 100 www.chinaindiadialogue.com 可绕地球赤道栽种树木按已达塞罕坝机械林场的森林覆盖率寒来暑往,沙地变林海,荒原成绿洲。半个多世纪,三代人耕耘。牢记使命 80% , 1 米株距排开, 艰苦创业 12 圈。 绿色发展 Saihanba is a cold alpine area in northern Hebei Province bordering the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region. It was once a barren land but is now home to 75,000 hectares of forest, thanks to the efforts make by generations of forestry workers in the past 55 years. Every year the forest purifies 137 million cubic meters of water and absorbs 747,000 tons of carbon dioxide. The forest produces 12 billion yuan (around US$1.8 billion) of ecological value annually, according to the Chinese Academy of Forestry. 可绕地球赤道栽种树木按已达塞罕坝机械林场的森林覆盖率寒来暑往,沙地变林海,荒原成绿洲。半个多世纪,三代人耕耘。牢记使命 CHINA-INDIA DIALOGUE CONTENTS ADMINISTRATIVE AGENCY: 主管: China International 中国外文出版发行事业局 (中国国际出版集团) 80% Publishing Group CHINDIA NEWS PUBLISHER: 主办、出版: China Pictorial 人民画报社 Memorabilia of 70th Anniversary of the Establishment of ADDRESS: 地址: , 33 Chegongzhuang Xilu, Haidian, 北京市海淀区 Beijing 100048, China 车公庄西路33号 Diplomatic Relations between China and India / p.02 1 米株距排开, 艰苦创业 PRESIDENT: Yu Tao 社长:于涛 12 EDITORIAL BOARD: 编委会: 圈。 OPENING ESSAY Yu Tao, Li Xia, 于 涛 、李 霞 、 He Peng, Bao Linfu, 贺 鹏 、鲍 林 富 、 Yu Jia, Yan Ying 于 佳 、闫 颖 CHARTING A NEW COURSE FOR EDITOR-IN-CHIEF: Li Xia 总编辑:李霞 EDITORIAL DIRECTORS: 编辑部主任: DRAGON-ELEPHANT TANGO 08 Qiao Zhenqi, Yin Xing 乔振祺、殷星 PERATIONS IRECTOR -

Tagore's Asian Voyages

THE NALANDA-SRIWIJAYA CENTRE, Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, Singapore, commemorates the 150th anniversary of World Poet Rabindranath Tagore Tagore’s Asian Voyages SELECTED SPEECHES AND WRITINGS ON RABINDRANATH TAGORE Nalanda-Sriwijaya Centre Logo in Full Color PROCESS COLOR : 30 Cyan l 90 Magenta l 90 Yellow l 20 Black PROCESS COLOR : 40 Cyan l 75 Magenta l 65 Yellow l 45 Black PROCESS COLOR : 50 Cyan l 100 Yellow PROCESS COLOR : 30 Cyan l 30 Magenta l 70 Yellow l 20 Black PROCESS COLOR : 70 Black PROCESS COLOR : 70 Cyan l 20 Yellow The Nalanda-Sriwijaya Centre at the Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, Singapore, pursues research on historical interactions among Asian societies and civilisations. It serves as a forum for comprehensive study of the ways in which Asian polities and societies have interacted over time through religious, cultural, and economic exchanges and diasporic networks. The Centre also offers innovative strategies for examining the manifestations of hybridity, convergence and mutual learning in a globalising Asia. http://nsc.iseas.edu.sg/ 1 CONTENTS 3 Preface Tansen Sen 4 Tagore’s Travel Itinerary in Southeast Asia 8 Tagore in China 10 Rabindranath Tagore and Asian Universalism Sugata Bose 19 Rabindranath Tagore’s Vision of India and China: A 21st Century Perspective Nirupama Rao 24 Realising Tagore’s Dream For Good Relations between India and China George Yeo 26 A Jilted City, Nobel Laureates and a Surge of Memories – All in One Tagorean Day Asad-ul Iqbal Latif 28 Tagore bust in Singapore – Unveiling Ceremony 30 Centenary Celebration Message Lee Kuan Yew 31 Messages 32 NSC Publications Compiled and designed by Rinkoo Bhowmik Editorial support: Joyce Iris Zaide 1 Nalanda-Sriwijaya Centre Projects Research Projects Lecture Series The Nalanda-Sriwijaya Centre The Nalanda-Sriwijaya Centre hosts pursues a range of research projects three lecture series focusing on intra- Asian interactions: The Nalanda-Sriwijaya within the following areas: 6. -

Durgotsav 2013 Is Inaugurated by Shri Ramalinga Reddy, Honourable

Durgotsav 2013 is inaugurated by Shri Ramalinga Reddy, Honourable Minister for Transport and the Minister in-charge for Bangalore Shri Ramalinga Reddy was born on 12th June, 1953 in Anekal. Holding a BSC., LLB from Bangalore University, he was a student leader. He was elected as Bangalore University Student Council twice. In 1977-78 he was elected as Senate Member of Bangalore University. He joined Indian National Congress in 1977 and became the Corporator of BMP in 1983. Elected continuously for 4 terms from Jayanagar Assembly Constituency between 1989 & 2004, he has the unique distinction of being the only MLA to get elected from Congress in 1994 out of 5 districts – Bangalore Urban, Bangalore Rural, Mysore, Mandya & Kodagu. He served as cabinet ministers in the governments of Shri Veerappa oily, Shri S M Krishna and Shri Dharam Singh. Married to Shrimati Chamundeshwari, he has one daughter and one son, both engineers. Reg. No: BNG(U)-BLR(S)/36/2006-07 PAN No: AAHTS-0529D Web: http://www.sarathionline.org Email: [email protected] Tel: 99018-54157, 98450-23363, 93428- 92911 Puja Committees FOUNDER CHAIRMAN Mr. Shyamal K Sen ADVISORS Mr. Shyamal K Sen, Mr. Alok K Basu, Mr. Shovan Roy, Mr. B P Roy CHAIRMAN Mr. Arnob Roy GENERAL SECRETARY Mr. Sujit K Chakravorty TREASURER Mr. Rupendu Chakraborty RECEPTION Mr. Shyamal K Sen, Mr. Alok K Basu, Mr. Arnob Roy COORDINATION Mr. Asis Paul PUJA & IMMERSION Mr. Saurabh Mathur Mr. Rupendu Chakraborty, Mrs. Kolapi Roy, Mrs. Mita Paul, Mrs. Anuradha Dasgupta, Mrs. Snigdha Basu, Mrs. Sagarika Ghosal, Mrs. Trinita Das, Mrs. -

Sriniketan: a Model Centre for Rural Reconstruction

International Journal of Humanities and Social Science Invention ISSN (Online): 2319 – 7722, ISSN (Print): 2319 – 7714 www.ijhssi.org ||Volume 6 Issue 11||November. 2017 || PP.57-61 Sriniketan: A Model Centre for Rural Reconstruction Dr Mahua Das, Prof. Dept.of Political Science, Women’s College, Calcutta, and Principal, Women’s College, Calcutta Corresponding Author: Dr Mahua Das --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Date of Submission: 23-10-2017 Date of acceptance: 09-11-2017 --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- I. INTRODUCTION The emergence of Sriniketan as a Rural Reconstruction Centre Over a century ago, Rabindranath Tagore, as a reaction to the colonial system of education, felt the need for a non-conventional and an integral system of education. To give shape to his ideas, he founded Visva- Bharati and its two centres – Santiniketan and Sriniketan, each having different programmes and objectives. The Institute of Rural Reconstruction was founded in 1922 at Surul at a distance of about three kilometres from Santiniketan. It was formally inaugurated on February 6, 1922 with Leonard Elmhirst as its first Director. Thus the second but contiguous campus of Visva-Bharati came to be located at a site which assumed the name of Sriniketan. The chief object was to help villagers and people to solve their own problems instead of a solution being imposed on them from outside. Sriniketan focused on agriculture and rural development with the co-operative efforts of the villagers themselves and its aim was to develop a better life for the people of rural India by educating them to be self-reliant and encouraging the revival of village arts and crafts.