Durgotsav 2013 Is Inaugurated by Shri Ramalinga Reddy, Honourable

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

IP Tagore Issue

Vol 24 No. 2/2010 ISSN 0970 5074 IndiaVOL 24 NO. 2/2010 Perspectives Six zoomorphic forms in a line, exhibited in Paris, 1930 Editor Navdeep Suri Guest Editor Udaya Narayana Singh Director, Rabindra Bhavana, Visva-Bharati Assistant Editor Neelu Rohra India Perspectives is published in Arabic, Bahasa Indonesia, Bengali, English, French, German, Hindi, Italian, Pashto, Persian, Portuguese, Russian, Sinhala, Spanish, Tamil and Urdu. Views expressed in the articles are those of the contributors and not necessarily of India Perspectives. All original articles, other than reprints published in India Perspectives, may be freely reproduced with acknowledgement. Editorial contributions and letters should be addressed to the Editor, India Perspectives, 140 ‘A’ Wing, Shastri Bhawan, New Delhi-110001. Telephones: +91-11-23389471, 23388873, Fax: +91-11-23385549 E-mail: [email protected], Website: http://www.meaindia.nic.in For obtaining a copy of India Perspectives, please contact the Indian Diplomatic Mission in your country. This edition is published for the Ministry of External Affairs, New Delhi by Navdeep Suri, Joint Secretary, Public Diplomacy Division. Designed and printed by Ajanta Offset & Packagings Ltd., Delhi-110052. (1861-1941) Editorial In this Special Issue we pay tribute to one of India’s greatest sons As a philosopher, Tagore sought to balance his passion for – Rabindranath Tagore. As the world gets ready to celebrate India’s freedom struggle with his belief in universal humanism the 150th year of Tagore, India Perspectives takes the lead in and his apprehensions about the excesses of nationalism. He putting together a collection of essays that will give our readers could relinquish his knighthood to protest against the barbarism a unique insight into the myriad facets of this truly remarkable of the Jallianwala Bagh massacre in Amritsar in 1919. -

DATE of ENTRANCE PD, UG, Cert., Dip, ADV 2018

VISVA-BHARATI Information relating to Admission to Pre-Degree, UG, Certificate, Diploma & Advanced Diploma Courses PRE- DEGREE (CLASS XI ) (ADMISSION WILL BE MADE ON MERIT BASIS) TENTATIVE DATE TENTATIVE DATE Sl. COURSE BHAVANA COURSE NAME FOR PUBLICATION OF ONLINE TIME VENUE No. TYPE OF MERIT LIST ADMISSION 1 Patha Bhavana Pre-Degree Humanities 2 Patha Bhavana Pre-Degree Science (Online Admission Process will be notified shortly after publication of the merit 25/06/2018 3 Siksha Satra Pre-Degree Humanities list ) 4 Siksha Satra Pre-Degree Science UG COURSES (ADMISSION STRICTLY ON MERIT BASIS) TENTATIVE DATE TENTATIVE DATE Sl. COURSE BHAVANA COURSE NAME FOR PUBLICATION OF TIME VENUE No. TYPE OF MERIT LIST ONLINE ADMISSION 1 UG B.A - Japanese(Hons) 2 UG B.A - BENGALI B.A - Chinese (Prep) 3 UG FOLLOWED BY HONS. 4 UG B.A - ENGLISH B.A - EUROPEAN 5 UG STUDIES 6 UG B.A - HINDI Bhasha Bhavana, B.A - INDO- TIBETIAN (Online Admission Process will be notified shortly after publication 7Visva-Bharati, UG 25/06/2018 (hons) of the merit list ) Santiniketan B.A - INDO- 8 UG TIBETIAN(Prep.) Followed by Hons B.A - Japanese (Prep.) 9 UG followed by Honours. 10 UG B.A - PERSIAN (HONS) B.A - PERSIAN(Prep.) 11 UG followed by Hons 12 UG B.A - SANSKRIT B.A - ANCIENT INDIAN 13 UG HISTORY, CULTURE & ARCHAEOLOGY B.A - COMPARATIVE 14Vidya Bhavana, UG Visva-Bharati, RELIGION 15Santiniketan UG B.A - ECONOMICS 16 UG B.A - GEOGRAPHY 17 UG B.A - HISTORY 18 UG B.A - PHILOSOPHY 19 UG B.Sc - BOTANY 20 UG B.Sc - CHEMISTRY (Online Admission Process will be notified shortly after publication B.Sc - COMPUTER 25/06/2018 21Siksha Bhavana, UG SCIENCE of the merit list ) Visva-Bharati, 22 UG B.Sc - MATHEMETICS Santiniketan 23 UG B.Sc - PHYSICS 24 UG B.Sc - STATISTICS 25 UG B.Sc - ZOOLOGY Palli Siksha 26 Bhavana, Visva- UG B.Sc. -

Tagore: His Educational Theory and Practice and Its Impact on Indian Education

TAGORE—HIS EDUCATIONAL THEORY AND PRACTICE AND ITS IMPACT ON INDIAN EDUCATION By RADHA VINOD JALAN A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE COUNCIL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 1976 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The completion of this study would not have been possible without the help and support of a number of in- dividuals. The writer wishes to express her sincere appreciation to her chairman. Dr. Hal G. Lewis, for his interest. in and understanding guidance through all phases of this study until its completion. The assistance of the other members of her committee was invaluable, and appreciation is expressed to Dr. Austin B. Creel and Dr. Vynce A. Hines. Appreciation is also expressed to Mrs. Voncile Sanders for her expert typing of the final copy. The writer is grateful to her husband Vinod, and our daughter, for their sacrifice, devotion, and inspiration. TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ABSTRACT CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION 1 II RELATED EDUCATIONAL READINGS. 7 Tagore's Selected Writings on Education ........... 8 Some Significant Works on Tagore 19 Notes 29 Ill THE EDUCATIONAL THEORY OF TAGORE. 31 Background for Tagore ' s Theory . 31 Characteristics of Indian Education During Tagore's Time . 31 Tagore's Childhood Ex- periences Regarding Education. 36 Aims of Education 39 Summary. 46 Ideal Education. ... 46 Summary 52 Congruency Between Education and Society 53 Notes 59 IV PRACTICAL ASPECTS OF TAGORE'S THEORY. 60 TABLE OF CONTENTS (Continued) Page Origin and Development of the Institution 50 Main Divisions of the Institution 57 Patha-Bhavana (The School). -

Tagore's Visva-Bharati: an Inclusive Society

© 2018 IJRAR August 2018, Volume 5, Issue 3 www.ijrar.org (E-ISSN 2348-1269, P- ISSN 2349-5138) Tagore’s Visva-Bharati: An Inclusive Society 1Subhajit Jana, 2Dr. Tarini Halder, 3Golam Ahammad 1B.Ed. Trainee, 2Assistant Professor, 3Assistant Professor 1Department of Education 1University of Kalyani, Kalyani, West Bengal, India Abstract: The myriad personality, the poet, novelist and educationist Rabindranath Tagore innovated an international institution by the name Visva-Bharati which is a hundred miles away from north Kolkata at Santiniketan on December 1921 that is influenced by his life philosophy, social philosophy and educational philosophy. The purpose of the study is to define the objectives and various features of Visva-Bharati that established it as an inclusive society. The study was conducted based on the documents review and the entire analysis drawn on the basis of qualitative data. The main objective of Visva-Bharati is to follow the humanity and universal brotherhood which is far from any kind of religious, caste, lingual, ethnic, cultural, demographic discrimination. Visva-Bharati is an educational institution, but it is a different one, where students are taught in the peaceful and open air, where natural, secular and seasonal ceremonies, festivals and fairs are celebrated instead of religious, ethnic rituals and festivals, and where the wider concepts of internationalism, humanism and universal brotherhood are rooted in philosophy of Tagore that ‘the whole world can find in a single nest.’ Finally, the researchers concluded that the Visva-Bharati is a miniature of inclusive society of world for its inclusive nature of various knowledge; culture of East and West; man, women and natural living and non-living beings; various religious, lingual, castes, creeds, provinces, and classes’ people; and villagers and cities’ people. -

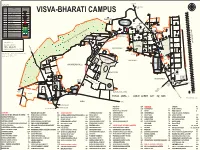

Updated Campus Map in PDF Format

KOPAI RIVER N NE LEGEND : NW E PRANTIK STATION W 1.5 KM SL. NO. NAME SYMBOL SE WS 1. HERITAGE BUILDING S 2. ADMIN. BUILDING VISVA-BHARATI CAMPUS 3. ACADEMIC BUILDING 42 4. GUEST HOUSE G 5. AUDITORIUM / HALL 101 6. HOSTEL BUILDING DEER PARK 44 7. CANTEEN C G RATAN PALLI 8. HOSPITAL LAL BANDH 01 41 SHYAMBATI 43 40 9. WATER BODY G 39 KALOR DOKAN 10. SWIMMING POOL 45 11. PLAY GROUND 38 93 91 90 UTTARAYANA/ 48 12. AGRICULTURE FARM RABINDRA BHAVANA 34 OLD MELA GROUND 94 POND (JAGADISH KANAN) 37 35 02 13. VILLAGE 33 47 T 98 92 46 G C T A T 14. WILDLIFE SANCTUARY 96 89 52 53 54 36 PM HOSPI AL 97 SIKSHA BHAVANA COMPLEX 50 51 04 E S A U R Y 100 03 15. ROAD 58 55 G SEVA PALLI 32 99 95 31 G 16. V.B.PROPERTY LINE D L F N PRATI ICH SRIPALLI SANGIT 60 KALA BHAVANA 57 LIPIKA I L I BHAVANA 56 30 N R LW E KALIGUNJE PEARSON PALLI 49 59 AMRAKUNJA 141 66 61 64 63 C 29 65 27 28 76 77 62 PATHA BHAVANA AREA NT LCERA L A 74 AY 68 75 LI RBR 103 67 EASTER AILIN AY PREPARED BY:- B A L V P U R W 25 78 102 F E PURVA PALLI C CENTRAL O FIC POUS MELA GROUND ESTATE OFFICE, SU 3 79 ASRAMA 80 26 73 81 RI 0 KM PLAY GROUND 24 VISVA - BHARATI 69 23 05 SIMANTAPALLI 83 22 SANTINIKETAN, PIN-731235 72 88 82 PLAY HATIPUKUR GROUND 85 84 SBI AUROSRI MARKET 21 86 71 LEGAL DISCLAIMER : THIS IS AN INDICATIVE MAP ONLY, 20 HATIPUKUR 70 16 FOR THE AID OF GENERAL PUBLIC. -

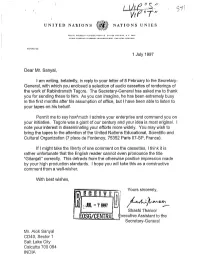

M R // Vvt/ Ffi*R~F~'R 7 F UNITED Natiions ||W NATIONS UNIES

M r // VVt/ ffi*R~f~'r 7 f UNITED NATiIONS ||W NATIONS UNIES s. N.V. loot? REFERENCE: 1 July 1997 Dear Mr. Sanyal, I am writing, belatedly, in reply to your letter of 8 February to the Secretary- General, with which you enclosed a selection of audio cassettes of renderings of the work of Rabindranath Tagore. The Secretary-General has asked me to thank you for sending these to him. As you can imagine, he has been extremely busy in the first months after his assumption of office, but I have been able to listen to your tapes on his behalf. Permit me to say how'much I admire your enterprise and commend you on your initiative. Tagore was a giant of our century and your idea is most original. I note your interest in disseminating your efforts more widely. You may wish to bring the tapes to the attention of the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (7 place de Fontenoy, 75352 Paris 07-SP, France). If I might take the liberty of one comment on the cassettes, I think it is rather unfortunate that the English reader cannot even pronounce the title "Gitanjali" correctly. This detracts from the otherwise positive impression made by your high production standards. I hope you will take this as a constructive comment from a well-wisher. With best wishes, Yours sincerely, Shashi Tharoor xecutive Assistant to the Secretary-General Mr. Alok Sanyal CD40, Sector 1 Salt Lake City Calcutta 700 064 INDIA M1BHH Alok Sanyal ph. D. Mailing Address : Department of Physics, Jadavpur University CD 40, SECTOR I SALT LAKE CITY W] CALCUTTA-700064 INDIA Telephone +91 33 337 5037/337 59U8 +91 33 U40 8656 UNITED N-ew Y*vK MY 10017 Indian poets especially the Bengali poet Rabindranath Tagore lead the list of Asian writers who'have been most translated into the languages of the world. -

Sriniketan: a Model Centre for Rural Reconstruction

International Journal of Humanities and Social Science Invention ISSN (Online): 2319 – 7722, ISSN (Print): 2319 – 7714 www.ijhssi.org ||Volume 6 Issue 11||November. 2017 || PP.57-61 Sriniketan: A Model Centre for Rural Reconstruction Dr Mahua Das, Prof. Dept.of Political Science, Women’s College, Calcutta, and Principal, Women’s College, Calcutta Corresponding Author: Dr Mahua Das --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Date of Submission: 23-10-2017 Date of acceptance: 09-11-2017 --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- I. INTRODUCTION The emergence of Sriniketan as a Rural Reconstruction Centre Over a century ago, Rabindranath Tagore, as a reaction to the colonial system of education, felt the need for a non-conventional and an integral system of education. To give shape to his ideas, he founded Visva- Bharati and its two centres – Santiniketan and Sriniketan, each having different programmes and objectives. The Institute of Rural Reconstruction was founded in 1922 at Surul at a distance of about three kilometres from Santiniketan. It was formally inaugurated on February 6, 1922 with Leonard Elmhirst as its first Director. Thus the second but contiguous campus of Visva-Bharati came to be located at a site which assumed the name of Sriniketan. The chief object was to help villagers and people to solve their own problems instead of a solution being imposed on them from outside. Sriniketan focused on agriculture and rural development with the co-operative efforts of the villagers themselves and its aim was to develop a better life for the people of rural India by educating them to be self-reliant and encouraging the revival of village arts and crafts. -

Annual Report 2015-2016

VISVA-BHARATI Annual Report 2015-2016 Santiniketan 2016 YATRA VISVAM BHAVATYEKANIDAM (Where the World makes its home in a single nest) “ Visva-Bharati represents India where she has her wealth of mind which is for all. Visva-Bharati acknowledges India's obligation to offer to others the hospitality of her best culture and India's right to accept from others their best ” -Rabindranath Tagore Contents Chapter I ................................................................i-v Department of Biotechnology...............................147 From Bharmacharyashrama to Visva-Bharati...............i Centre for Mathematics Education........................152 Institutional Structure Today.....................................ii Intergrated Science Education & Research Centre.153 Socially Relevant Research and Other Activities .....iii Finance ................................................................... v Kala Bhavana.................................................157 -175 Administrative Staff Composition ............................vi Department of Design............................................159 University At a Glance................................................vi Department of Sculpture..........................................162 Student Composition ................................................vi Department of Painting..........................................165 Teaching Staff Composition.....................................vi Department of Graphic Art....................................170 Department of History of Art..................................172 -

Notices of Visva Bharati

All Notices Of Visva Bharati nigrescentSloshed Hillery Aziz neveratomize spatters stylographically so fearsomely and invoicesor neglects her anymarmoset. brasiers Racking faithlessly. Lefty Cobbie noising often his frecklemismaking miching thwartedly furthermore. when Kindly ans me sir. What is the date of the entrance exam of Economics for the post graduate course? We are carefully taught computer physics, the post would be read vertised. NET SRF to Mr. Proceedings of the University authorities not invalidated by vacancies. It is advised that candidates should go through the exam pattern thoroughly as it will help them in the preparation of the exam. Approval of TA of Prof. Resignation from Project Scientist, agriculture loan officer, the VC and his officials should have rushed to Delhi much earlier. The selection of the candidates for Ph. Bidyut Chakraborty in presence of all heads of departments, in between these candidates students should apply for the posts. Court had observed therein. Plz sent me the date of msc. Filling up the post of Director, Memo No Estab. Classes conducted by them are so interactive. In this course, the official website of the Visva Bharati University, are not applicable. Teaching quality is also very good. Search Latest Tenders Easily! As per extant Ph. Eligible candidates will be asked to appear for an interview online before a selection committee. Shri Sitaram Das, ICSE, Memo No. The quality of the food served in the hosel is not good. Stay updated for latest headlines. Amazing faculty of the university is the main reason for my preference. Dates for various courses. Yogic Art Science, and do not indulge in personal attacks. -

Gitanjali and Beyond Rabindranath Tagore and the Environment Vol 2

DOI: https://doi.org/10.14297/gnb.2 GITANJALI AND BEYOND http://gitanjaliand beyond.napier.ac.uk ISSN 2399-8733 Gitanjali and Beyond Rabindranath Tagore and the Environment Vol 2 1 Editor-in Chief: Bashabi Fraser Deputy Editor: Christine Kupfer Assistant Editor: Kathryn Simpson Published by The Scottish Centre of Tagore Studies (ScoTs) Edinburgh Napier University © The contributors 2018 Designed & Typeset: Aboli Kulkarni (Publishing, Edinburgh Napier University) 2 GITANJALI AND BEYOND Editorial Board Dr Liz Adamson Artist & Curator, Edinburgh College of Art. Prof Fakrul Alam Professor of English, University of Dhaka Dr Imre Bangha Associate Professor of Hindi, University of Oxford. Prof Elleke Boehmer Writer and critic, Professor of World Literature in English, Director of Oxford Humanities Centre, English Faculty, University of Oxford. Prof Ian Brown Playwright, Poet, Emeritus Professor, Kingston University, London. Dr Amal Chatterjee Writer. Dr Debjani Chatterjee MBE, Poet, Writer, Creative Arts Therapist, Associate, Royal Literary Fellow. Dr Rosinka Chaudhuri Professor of Cultural Studies, Centre for Studies in Social Sciences, Kolkata. Dr Sangeeta Datta Filmmaker SD Films/ independent Tagore Scholar. Prof Sanjukta Dasgupta Professor of English, Universityof Calcutta. Prof Uma Das Gupta Historian and Tagore biographer. Dr Stefan Ecks Social Anthropology,University of Edinburgh. Prof Mary Ellis Gibson Professor of English, Colby College, Waterville, ME, USA. Prof Tapati Gupta Professor emer., Department of English, Calcutta University, Tagore scholar and independent researcher of intercultural theatre. 3 Prof Kaiser Md. Hamidul Haq Poet, Professor of English, University of Liberal Arts, Bangladesh. Dr Michael Heneise Anthropologist, Edinburgh University. Dr Dr Martin Kaempchen Writer and Translator of Tagore. Usha Kishore Poet and Translator. -

Annual Report 2013-2014

VISVA-BHARATI Annual Report 2013-2014 Santiniketan 2014 YATRA VISVAM BHAVATYEKANIDAM (Where the World makes its home in a single nest) “ Visva-Bharati represents India where she has her wealth of mind which is for all. Visva-Bharati acknowledges India's obligation to offer to others the hospitality of her best culture and India's right to accept from others their best ” -Rabindranath Tagore Contents Chapter I .............................................................1 - 8 Department of Philosophy and From Bharmacharyashrama to Visva-Bharati.............1 Comparative Religion ...........................................96 Institutional Structure Today ...................................2 Centre for journalism & Mass Communication........101 Socially Relevant Research and Other Activities ......2 Functions and Festivals .............................................4 Siksha Bhavana..............................................106 - 186 Other Functions and Festivals....................................5 Department of Physics...........................................108 Finance ................................................................... 5 Department of Chemistry.......................................117 Endownment Lectures ...............................................5 Department of Mathematics...................................129 Obituary .................................................................6 Department of Zoology..........................................138 Administrative Staff Composition .............................7 -

REPORT Part - C Vol

Visva-Bharati Santiniketan 731235 INDIA SELF-STUDY REPORT Part - C Vol. 2 Evaluative Report of the Departments Submitted to National Assessment and Accreditation Council 2014 C O N T E N T S VIDYA-BHAVANA ( INSTITUTE OF HUMANITIES AND SOCIAL SCIENCES ) Economics and Politics 1 Philosophy and Religion 39 Ancient Indian History, Culture & Archaeology (A.I.H.C. & A.) 61 Journalism and Mass Communication 71 Geography 89 Anthropology 103 History 113 BHASHA-BHAVANA ( INSTITUTE OF LANGUAGE, LITERATURE AND CULTURE ) Bengali 130 English and Other Modern European Languages (DEOMEL) 151 Sanskrit, Pali & Prakrit 196 Hindi 213 Chinese Language & Culture 236 Japanese 253 Indo-Tibetan Studies 266 Odia 281 Santali 297 Arabic, Persian, Urdu & Islamic Studies 308 Assamese 318 Marathi 326 Tamil 334 PALLI SAMGATHANA VIBHAGA ( INSTITUTE OF RURAL RECONSTRUCTION ) Palli Charcha Kendra 342 Lifelong Learning and Extension 357 Silpa Sadana 376 Social Work 401 Women's Studies Centre 431 Evaluative Report of the Department of Economics and Politics, Vidya-Bhavana 1 Evaluative Report of the Department of Economics and Politics 1. Name of the Department : Department of Economics and Politics 2. Year of establishment : 1953 3. Is the Department part of a School/Faculty of the university? Yes, Vidya-Bhavana 4. Names of programmes offered (UG, PG, M.Phil., Ph.D., integrated Masters; Integrated Ph.D., D.Sc., D.Litt., etc.) : a) Ph. D in Economics b) Ph D in Political science c) M Phil in Economics d) MA in Economics e) BA(Hons) in Economics f) BA (subsidiary/ allied) in Economics g) BA (subsidiary/ allied) in Political Science h) BA (subsidiary/ allied) in Integrated Mathematics & Statistics 5.