A Study of Statelessness, United Nations, August 1949, Lake Success

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Constituent Assembly Debates

Friday, 12th August, 1949 Volume IX to 18-9-1949 CONSTITUENT ASSEMBLY DEBATES OFFICIAL REPORT REPRINTED BY LOK SABHA SECRETARIAT, NEW DELHI SIXTH REPRINT 2014 Printed at JAINCO ART INDIA, NEW DELHI. THE CONSTITUENT ASSEMBLY OF INDIA President: THE HONOURABLE DR. RAJENDRA PRASAD. Vice-President: DR. H.C. MOOKHERJEE. Constitutional Adviser: SIR B.N. RAU, C.I.E. Secretary: SHRI H.V.R. IENGAR, C.I.E., I.C.S. Joint Secretary: MR. S.N. MUKHERJEE. Deputy Secretary: SHRI JUGAL KISHORE KHANNA. Marshal: SUBEDAR MAJOR HARBANS LAL JAIDKA. CONTENTS Volume IX—30th July to 18th September 1949 PAGES PAGES Saturday, 30th July 1949— Thrusday, 11th August 1949— Taking the Pledge & Signing the Draft Constitution—(contd.) ............... 351—391 Register ............................................. 1 [Articles 5 and 6 considered]. Draft Constitution—(contd.) ............... 2—42 Friday, 12th August 1949— [Articles 79-A, 104, 148-A, 150, Draft Constitution—(contd.) ............... 393—431 163-A and 175 considered]. [Articles 5 and 6 considered]. Monday, 1st August 1949— Thursday, 18th August 1949— Draft Constitution—(contd.) ............... 43—83 Government of India Act, 1935 [Articles 175, 172, 176, 83, 127, (Amendment) Bill ............................ 433—472 210, 211, 197, 212, 214 and 213 considered]. Friday, 19th August 1949— Tuesday, 2nd August 1949— Draft Constitution—(contd.) ............ 473—511 Taking the Pledge and Signing the [Articles 150, 215-A, 189, 190, Register ............................................. 85 250 and 277 considered]. Draft Constitution—(contd.) ............... 85—127 Saturday, 20th August 1949— [Articles 213, 213-A, 214 and Draft Constitution—(contd.) ............... 513—554 275 considered]. [Articles 277, 279-A and Wednesday, 3rd August 1949— 280 considered]. Draft Constitution—(contd.) ............... 129—163 Monday, 22nd August 1949— [Articles 276, 188, 277-A, 278 Draft Constitution—(contd.) .............. -

Militärgerichtsbarkeit in Österreich (Circa 1850–1945)

BRGÖ 2016 Beiträge zur Rechtsgeschichte Österreichs Martin MOLL, Graz Militärgerichtsbarkeit in Österreich (circa 1850–1945) Military jurisdiction in Austria, ca. 1850–1945 This article starts around 1850, a period which saw a new codification of civil and military penal law with a more precise separation of these areas. Crimes committed by soldiers were now defined parallel to civilian ones. However, soldiers were still tried before military courts. The military penal code comprised genuine military crimes like deser- tion and mutiny. Up to 1912 the procedure law had been archaic as it did not distinguish between the state prosecu- tor and the judge. But in 1912 the legislature passed a modern military procedure law which came into practice only weeks before the outbreak of World War I, during which millions of trials took place, conducted against civilians as well as soldiers. This article outlines the structure of military courts in Austria-Hungary, ranging from courts responsible for a single garrison up to the Highest Military Court in Vienna. When Austria became a republic in November 1918, military jurisdiction was abolished. The authoritarian government of Chancellor Engelbert Dollfuß reintroduced martial law in late 1933; it was mainly used against Social Democrats who staged the February 1934 uprising. After the National Socialist ‘July putsch’ of 1934 a military court punished the rioters. Following Aus- tria’s annexation to Germany in 1938, German military law was introduced in Austria. After the war’s end in 1945, these Nazi remnants were abolished, leaving Austria without any military jurisdiction. Keywords: Austria – Austria as part of Hitler’s Germany –First Republic – Habsburg Monarchy – Military Jurisdiction Einleitung und Themenübersicht allen Staaten gab es eine eigene, von der zivilen Justiz getrennte Strafgerichtsbarkeit des Militärs. -

GATT Bibliography, 1947-1953

FIRST EDITION GATT BIBLIOGRAPHY- 1947 - 1953 The text of the GATT Selected GATT publications A chronological list of references to the GATT GATT Secretariat Palais des Nations Geneva Switzerland March 1954 MGT/7/54 GATT BIBLIOGRAPHY This bibliography is a list of books, pamphlets, articles in periodicals, newspaper reports and editorials, and miscellaneous items including texts of lectures, which refer to the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade. It covers a period of approximately seven years. For six of these years - from the beginning of 1948 - the GATT has been in operation. The purpose of the list is a practical one: to provide sources of reference for historians, researchers and students. The list, it must be emphasized, is limited to the formation and operation of the GATT; for masons *f length, the history of the Havana Charter and its preparation and references to the proposed International Trade Organization,'which has not been brought into being, have been somewhat rigidly excluded, while emphasis has been put on references that show the operational aspects of the GATT. The bibliography is divided into the following sections: 1. • the text' of the GATT and governmental publications; 2. selected GATT publications; (the full list of GATT publications is .obtainable from the secretariat on request) 3. a chronological listing of references to the GATT. This has been subdivided into the following periods, the references being listed alphabetically in each period: 1947 including the Geneva tariff negotiations (April- August), and the completion of the GATT 1948 including the first two sessions of the GATT (March at Havana, and August-September at Geneva) 1949 ,... -

[Intervention from the Director (DER)

[Intervention from the Director (DER): • I am pleased to tell you that 2011 is a very special year for refugees, not only in the context of the commemorations of the 1951 Refugee Convention and the 1961 Convention on the Reduction of Statelessness, but also because it marks the 150th anniversary of the birth of Fridtjof Nansen. • As many of you know, Nansen was not only a renowned scientist and explorer, but in 1921 was appointed the first High Commissioner for Refugees by the League of Nations. He immediately undertook the formidable task of helping repatriate hundreds of thousands of refugees from World War I, assisting them to acquire legal status and attain economic independence. Nansen recognized that one of the main problems refugees faced was their lack of internationally recognized identification papers, which in turn complicated their request for asylum. This Norwegian visionary introduced the so-called "Nansen passport," which was the first legal instrument used for the international protection of refugees. • UNHCR established the Nansen Refugee Award in his honour in 1954. It is given to a person or group who has demonstrated outstanding service for and commitment to the cause of refugees. • Following the tradition started last year to combine the Nansen Refugee Award ceremony with the High Commissioner’s welcoming reception on the occasion of the opening of the Executive Committee meeting, I am pleased to announce that they will be held on Monday, 3 October, at the Bâtiment des Forces Motrices in Geneva. • This year, the award ceremony will be broadcasted in a number of countries around the world for the first time. -

Geneva Conventions of 12 August 1949

THE GENEVA CONVENTIONS OF 12 AUGUST 1949 AUGUST 12 OF CONVENTIONS THE GENEVA THE GENEVA CONVENTIONS OF 12 AUGUST 1949 0173/002 05.2010 10,000 ICRC Mission The International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) is an impartial, neutral and independent organization whose exclusively humanitarian mission is to protect the lives and dignity of victims of armed conflict and other situations of violence and to provide them with assistance. The ICRC also endeavours to prevent suffering by promoting and strengthening humanitarian law and universal humanitarian principles. Established in 1863, the ICRC is at the origin of the Geneva Conventions and the International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement. It directs and coordinates the international activities conducted by the Movement in armed conflicts and other situations of violence. THE GENEVA CONVENTIONS OF 12 AUGUST 1949 THE GENEVA CONVENTIONS OF 1949 1 Contents Preliminary remarks .......................................................................................................... 19 GENEVA CONVENTION FOR THE AMELIORATION OF THE CONDITION OF THE WOUNDED AND SICK IN ARMED FORCES IN THE FIELD OF 12 AUGUST 1949 CHAPTER I General Provisions ....................................................................................................... 35 Article 1 Respect for the Convention ..................................................................... 35 Article 2 Application of the Convention ................................................................ 35 Article 3 Conflicts not of an international -

Europe and the Migration Crisis: the Response of the Eu Member States

Europe the Response and the Migration of the EU Member Crisis: States Ondřej Filipec, Valeriu Mosneaga and Aaron T. Walter EUROPE AND THE MIGRATION CRISIS: THE RESPONSE OF THE EU MEMBER STATES Ondřej Filipec, Valeriu Mosneaga Aaron T. Walter 2018 Gdańsk We gratefully acknowledge receipt of the grant Jean Monnet Chair in Migration “Migration: The Challenge of European States” under the Jean Monnet Chair scheme awarded in 2016 to the Faculty of Social Sciences, University of Ss. Cyril and Methodius in Trnava, Slovakia. Europe and the Migration Crisis: the Response of the EU Member States © Ondřej Filipec, Valeriu Mosneaga and Aaron T. Walter Authors: Ondřej Filipec (Chapter 3, 6, 8, 9) Valeriu Mosneaga (Chapter 4, 5, 12) Aaron T. Walter (Chapter 2, 7, 10, 11) Valeriu Mosneaga and Dorin Vaculovschi (Chapter 1) Reviewed by: Dr. Rafał Raczyński (Muzeum Emigracji w Gdyni) Dr. Alexander Onufrák (Pavol Jozef Šafárik University in Košice) Corrections: Aaron T. Walter Technical Editor, Graphic Design and Cover: AllJakub rights Bardovič reserved: no part of this publication shall be reproduced in any form including (but not limited to) copying, scanning, recording or any other form without written consent of the author or a person on which author would transfer his material authors’ rights. © Stowarzyszenie Naukowe Instytut Badań nad Polityką Europejską ISBN 978-83-944614-7-8 Content Introduction: Time of Choosing......................................................................9 Part I 1 Migration in Theories....................................................................................17 -

Children's Right to a Nationality

OPEN SOCIETY JUSTICE INITIATIVE Children’s right to a nationality Statelessness affects more than 12 million people around the world, among whom the most vulnerable are children. The Open Society Justice Initiative estimates that as many as 5 million may be minors. The consequences of lack of nationality are numerous and severe. Many stateless children grow up in extreme poverty and are denied basic rights and services such as access to education and health care. Stateless children‟s lack of identity documentation limits their freedom of movement. They are subject to arbitrary deportations and prolonged detentions, are vulnerable to social exclusion, trafficking and exploitation—including child labor. Despite its importance, children‟s right to a nationality rarely gets the urgent attention it needs. Children’s right to nationality The right to a nationality is protected under At the very least, the right to acquire a nationality under international law. The Universal Declaration of Human the CRC should be understood to mean that children Rights provides a general right to nationality under have a right to nationality in their country of birth if article 15. The international human rights treaties— they do not acquire another nationality from birth—in including the Convention on the Rights of the Child other words, if they would otherwise be stateless. In (CRC) and the International Covenant on Civil and fact, this particular principle is recognized in regional Political Rights (ICCPR)—as well as the Convention on systems as well as in the Convention on the Reduction the Reduction of Statelessness, provide particular norms of Statelessness. -

Rapoport Center Human Rights Working Paper Series 1/2019

Rapoport Center Human Rights Working Paper Series 1/2019 Striving for Solutions: African States, Refugees, and the International Politics of Durable Solutions Olajumoke Yacob-Haliso Creative Commons license Attribution Non-Commercial No Derivatives. This text may be downloaded for personal research purposes only. Any additional reproduction for other purposes, whether in hard copy or electronically, requires the consent of the Rapoport Center Human Rights Working Paper Series and the author. For the full terms of the Creative Commons License, please visit www.creativecommons.org. Dedicated to interdisciplinary and critical dialogue on international human rights law and discourse, the Rapoport Center’s Working Paper Series (WPS) publishes innovative papers by established and early-career researchers as well as practitioners. The goal is to provide a productive environment for debate about human rights among academics, policymakers, activists, practitioners, and the wider public. ISSN 2158-3161 Published in the United States of America The Bernard and Audre Rapoport Center for Human Rights and Justice at The University of Texas School of Law 727 E. Dean Keeton St. Austin, TX 78705 https://law.utexas.edu/humanrights/ https://law.utexas.edu/humanrights/project-type/working-paper-series/ 1 ABSTRACT How do international structure and African agency constrain or propel the search for truly “durable solutions” to the African refugee situation? This is the central question that I seek to answer in this paper. I would argue that existing approaches to resolving refugee issues in Africa are problematic, and key to addressing this dilemma is a clear and keen understanding and apprehension of the phenomenon as grounded in history, states’ self-interested actions, international politics, and humanitarian practice. -

The Rise and Fall of an Internationally Codified Denial of the Defense of Superior Orders

xv The Rise and Fall of an Internationally Codified Denial of the Defense of Superior Orders 30 Revue De Droit Militaire Et De Droit De LA Guerre 183 (1991) Introduction s long as there have been trials for violations of the laws and customs of A war, more popularly known as "war crimes trials", the trial tribunals have been confronted with the defense of "superior orders"-the claim that the accused did what he did because he was ordered to do so by a superior officer (or by his Government) and that his refusal to obey the order would have brought dire consequences upon him. And as along as there have been trials for violations of the laws and customs ofwar the trial tribunals have almost uniformly rejected that defense. However, since the termination of the major programs of war crimes trials conducted after World War II there has been an ongoing dispute as to whether a plea of superior orders should be allowed, or disallowed, and, if allowed, the criteria to be used as the basis for its application. Does international action in this area constitute an invasion of the national jurisdiction? Should the doctrine apply to all war crimes or only to certain specifically named crimes? Should the illegality of the order received be such that any "reasonable" person would recognize its invalidity; or should it be such as to be recognized by a person of"ordinary sense and understanding"; or by a person ofthe "commonest understanding"? Should it be "illegal on its face"; or "manifesdy illegal"; or "palpably illegal"; or of "obvious criminality,,?1 An inability to reach a generally acceptable consensus on these problems has resulted in the repeated rejection of attempts to legislate internationally in this area. -

Garrison, Mary

The Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History Project MARY LEE GARRISON Interviewed by: Charles Stewart Kennedy Initial Interview Date: November 30, 2005 Copyright 2020 ADST TABLE OF CONTENTS Background Born in U.S. Army hospital at Valley Forge, 1951 BA in 1973, Georgetown University 1969–1973 Entered the Foreign Service 1973 Washington, DC—Foreign Service Institute 1973–1974 French Language Student Saigon, Vietnam—Consular Assignment 1974–1975 American Citizen Services Remnants of the Vietnam War Withdrawal from Vietnam Washington, DC—Bureau of African Affairs, Special Assistant to the 1975–1976 Assistant Secretary Angola Rhodesia The Cold War in Africa Kinshasa, Zaire—Economic Officer 1976–1979 [Now the Democratic Republic of the Congo] Commercial Policy Congolese Government and Mobotu The Shaba War Washington, DC—Bureau of African Affairs, Congo Desk Officer 1979–1981 Congressional Testimony Aid to Congo European Powers in Congo Washington, DC—Bureau of African Affairs, Deputy Director of 1981–1983 Economic Policy Staff IMF Programs 1 Washington, DC— Foreign Service Institute 1983–1984 Hungarian Language Student Budapest, Hungary—Economic Officer 1974–1975 “Goulash Communism” Hungarian Immigration to the U.S. The Hungarian Economy The Eastern Bloc The Soviet Union Washington, DC—Office of Inspector General 1986–1987 Housing Standards Washington, DC—Economic and Business Bureau, Food Policy 1987–1989 U.S.-Canada Free Trade Agreement Product Regulation Washington, DC—Economic and Business Bureau, Deputy Director of 1989–1991 Office of Developing Country Trade Mexico and NAFTA Counterfeiting of Compact Disks Washington, DC—Bureau of American Republics Affairs 1991–1992 Economic Policy Staff Officer Agency for International Development (AID) Monterrey, Mexico—Economic Officer 1992–1996 NAFTA Maquiladoras in Mexico Bribery 1994 Election National Action Party Technology Use in the Embassy Washington, DC—Bureau of Intelligence and Research 1996-1999 African Economic Analyst Interview Incomplete. -

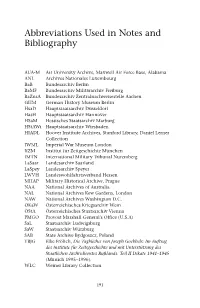

Abbreviations Used in Notes and Bibliography

Abbreviations Used in Notes and Bibliography AUA-M Air University Archive, Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama ANL Archives Nationales Luxembourg BaB Bundesarchiv Berlin BaMF Bundesarchiv Militärarchiv Freiburg BaZnsA Bundesarchiv Zentralnachweisestelle Aachen GHM German History Museum Berlin HsaD Hauptstaatsarchiv Düsseldorf HasH Hauptstaatsarchiv Hannover HSaM Hessisches Staatsarchiv Marburg HStAWi Hauptstaatsarchiv Wiesbaden HIADL Hoover Institute Archives, Stanford Library, Daniel Lerner Collection IWML Imperial War Museum London IfZM Institut für Zeitgeschichte München IMTN International Military Tribunal Nuremberg LaSaar Landesarchiv Saarland LaSpey Landesarchiv Speyer LWVH Landeswohlfahrtsverband Hessen MHAP Military Historical Archive, Prague NAA National Archives of Australia NAL National Archives Kew Gardens, London NAW National Archives Washington D.C. OKaW Österreichisches Kriegsarchiv Wein ÖStA Österreichisches Staatsarchiv Vienna PMGO Provost Marshall General’s Office (U.S.A) SaL Staatsarchiv Ludwigsburg SaW Staatsarchiv Würzburg SAB State Archive Bydgoszcz, Poland TBJG Elke Frölich, Die Tagbücher von Joseph Goebbels: Im Auftrag des Institute für Zeitsgeschichte und mit Unterstützung des Staatlichen Archivdienstes Rußlands. Teil II Dikate 1941–1945 (Münich 1995–1996). WLC Weiner Library Collection 191 Notes Introduction: Sippenhaft, Terror and Fear: The Historiography of the Nazi Terror State 1 . Christopher Hutton, Race and the Third Reich: Linguistics, Racial Anthropology and Genetics in the Third Reich (Cambridge 2005), p. 18. 2 . Rosemary O’Kane, Terror, Force and States: The Path from Modernity (Cheltham 1996), p. 19. O’Kane defines a system of terror, as one that is ‘distinguished by summary justice, where the innocence or guilt of the victims is immaterial’. 3 . See Robert Thurston, ‘The Family during the Great Terror 1935–1941’, Soviet Studies , 43, 3 (1991), pp. 553–74. -

The Nationality Law of the People's Republic of China and the Overseas Chinese in Hong Kong, Macao and Southeast Asia

NYLS Journal of International and Comparative Law Volume 5 Article 6 Number 2 Volume 5, Numbers 2 & 3, 1984 1984 The aN tionality Law of the People's Republic of China and the Overseas Chinese in Hong Kong, Macao and Southeast Asia Tung-Pi Chen Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.nyls.edu/ journal_of_international_and_comparative_law Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Chen, Tung-Pi (1984) "The aN tionality Law of the People's Republic of China and the Overseas Chinese in Hong Kong, Macao and Southeast Asia," NYLS Journal of International and Comparative Law: Vol. 5 : No. 2 , Article 6. Available at: https://digitalcommons.nyls.edu/journal_of_international_and_comparative_law/vol5/iss2/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@NYLS. It has been accepted for inclusion in NYLS Journal of International and Comparative Law by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@NYLS. THE NATIONALITY LAW OF THE PEOPLE'S REPUBLIC OF CHINA AND THE OVERSEAS CHINESE IN HONG KONG, MACAO AND SOUTHEAST ASIA TUNG-PI CHEN* INTRODUCTION After thirty years of existence, the Government of the People's Re- public of China (PRC) enacted the long-awaited Nationality Law in 1980.1 Based on the PRC Government's enduring principle of racial and sexual equality, the new law is designed to reduce dual nationality and statelessness by combining the principles of jus sanguinis and jus soli to determine nationality at birth. The need for a Chinese national- ity law had long been recognized, but it was not until the adoption of the "open door" policy in 1978 after the downfall of the "Gang of Four," as well as the institution of codification efforts, that the urgency of the task was recognized.