The New Zealand Military Service Boards and Conscientious Objectors

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Dunedin Lawyer's Seed of Dissent: A.R. Barclay, the Boer War and The

1 The Dunedin lawyer’s seed of dissent: A.R. Barclay, the Boer war and the socialist origins of Archibald Baxter’s pacifism 1. Introduction: the case for a consideration of the socialist aspect of Baxter’s pacifism Archibald Baxter’s ‘We Will Not Cease’ is an iconic and rightfully famous pacifist statement. Narrated in a lucid and unadorned style, Baxter’s story exposes the horrors and hypocrisy of war. It is also a memoir of courage and resistance, in which a humble farmer from Otago is pitted against the military authorities of an Empire. As Steven Loveridge points out, the ‘success of the text owes much to its narration and the imparted impression of Baxter’s strength of character against hostile circumstances1.’ Baxter’s moral character is tenderly recalled by his wife Millicent, who picks out her son’s poem ‘To My Father’ as her favourite poem, and cites this moving verse: …. I have loved You more than my own good, because you stand For country pride and gentleness, engraved In forehead lines, veins swollen on the hand; Also, behind slow speech and quiet eye The rock of passionate integrity2. 1 Loveridge, S. ‘Calls To Arms: New Zealand Society and Commitment to the Great War’. VUP. Wellington, 2014. p. 167 2 Baxter, M. ‘The Memoirs of Millicent Baxter’. Cape Catley, 1981. p.110 2 This verse is a brilliant and moving summary of the moral qualities of Archibald Baxter, which appear to be intimately wedded to the land itself. We think of the resolute and immensely strong will of Baxter resisting the pressure to fight as a soldier in the trenches of WW1 – the ‘rock of passionate integrity’. -

The 47Th Voyager Media Awards. #VMA2020NZ

Welcome to the 47th Voyager Media Awards. #VMA2020NZ Brought to you by the NPA and Premier sponsor Supporting sponsors Canon New Zealand, nib New Zealand, ASB, Meridian Energy, Bauer Media Group, NZ On Air, Māori Television, Newshub, TVNZ, Sky Sport, RNZ, Google News Initiative, Huawei, Ovato, BusinessNZ, Asia Media Centre, PMCA, E Tū , Science Media Centre, Air New Zealand and Cordis, Auckland. Order of programme Message from Michael Boggs, chair of the NPA. Jane Phare, NPA Awards Director, Voyager Media Awards Award ceremony hosts Jaquie Brown and James McOnie Jaquie Brown James McOnie Jaquie and James will read out edited versions of the judges’ comments during the online ceremony. To view the full versions go to www.voyagermediaawards.nz/winners2020 after the ceremony. In some cases, judges have also added comments for runners-up and finalists. Winners’ and finalists’ certificates, and trophies will be sent to media groups and entrants after the online awards ceremony. Winners of scholarship funds, please contact Awards Director Jane Phare, [email protected]. To view the winners’ work go to www.voyagermediaawards.nz/winners2020 To view the list of judges, go to www.voyagermediaawards.nz/judges2020 Information about the historic journalism awards, and the Peter M Acland Foundation, is at the end of this programme and on www.voyagermediaawards.nz Order of presentation General Best headline, caption or hook (including social media) Judges: Alan Young and John Gardner Warwick Church, NZ Herald/NZME; Rob Drent, Devonport Flagstaff and Rangitoto Observer; Warren Gamble, Nelson Mail/Stuff; and Barnaby Sharp, Nelson Mail/Stuff. Best artwork/graphics (including interactive/motion graphics) Judges: Daron Parton and Melissa Gardi 1 News Design Team/TVNZ; Richard Dale, NZ Herald/NZME; Cameron Reid and Vinay Ranchhod, Newshub/MediaWorks; Toby Longbottom, Phil Johnson and Suyeon Son, Stuff Circuit/Stuff; and Toby Morris, The Spinoff. -

TF Years 11-13 Truth and Fiction

YEARS 11–13 FIRST WORLD WAR INQUIRY GUIDE Truth and Fiction Acknowledgments The Ministry of Education would like to thank the following individuals and groups who helped to develop this guide: Dylan Owen and Services to Schools (National Library of New Zealand Te Puna Mātauranga o Aotearoa); Steve Watters (Senior Historian/Educator, WW100 Programme Office and History Group, Ministry for Culture and Heritage); Cognition Education Limited; the First World War Project Advisory Group; Hobsonville Point Secondary School; Mount Roskill Grammar School; Wellington College; Western Springs College. The texts, photographs, and other images sourced as stated below are fully acknowledged on the specified pages. The image on the cover and on page 8 is courtesy of Te Papa Tongarewa; the image of the postcard on page 10, the photograph of Archibald Baxter on page 13, the painting of the landing at Anzac Cove on page 14 and, the two cartoons on page 22 are all used with permission from the Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington; the poem on page 10 is used with permission from Papers Past; the painting on page 11 is used with permission from Bob Kerr; the photographs on page 12, the painting on page 16, and the painting on page 19 are used with permission from Archives New Zealand; the book cover photograph on page 13 is used with permission from Auckland City Libraries; the photograph of the landing at Anzac Cove on page 14 and, the painting Menin Gate at Midnight and Will Dyson cartoons on page 20 are used with permission from the Australian War Memorial; -

Unsung Heroes Clay Nelson © 26 April 2015 Auckland Unitarian Church

Unsung Heroes Clay Nelson © 26 April 2015 Auckland Unitarian Church It was December 1, 1969. A day I remember well. It was during my third year of university. My roommates and I were gathered around the radio as was every American male born between 1946 and 1950. It was the first draft lottery. For each day of the year one of 366 numbers would be drawn. If a number lower than 195 was assigned to your birthday it meant you would be conscripted in the next year or as soon as your student deferment ended to fight in an unpopular war in Southeast Asia. My roommate, who was also destined to become a minister one day, and I had both applied for Conscientious Objector status. Not being from traditionally pacifist churches such as the Quakers, Brethren and Seventh Day Adventists our chances were not good. My roommate’s number was 128; mine was 313. It was a day of muted relief for me, for although I was in the clear, he was not. My only regret was that I would never learn if I could have convinced the draft board to grant me CO status. To apply for CO status was for me not done lightly or easily. I was not raised in a pacifist family. My father enlisted in World War II, lying about his age to do so. He was conscripted during the Korean War, but was struck down with polio shortly after being inducted. My church did not teach pacifist principles and was closely associated with the power of the state. -

August 2010 PROTECTION of AUTHOR ' S C O P Y R I G H T This

THE UNIVERSITY LIBRARY PROTECTION OF AUTHOR ’S COPYRIGHT This copy has been supplied by the Library of the University of Otago on the understanding that the following conditions will be observed: 1. To comply with s56 of the Copyright Act 1994 [NZ], this thesis copy must only be used for the purposes of research or private study. 2. The author's permission must be obtained before any material in the thesis is reproduced, unless such reproduction falls within the fair dealing guidelines of the Copyright Act 1994. Due acknowledgement must be made to the author in any citation. 3. No further copies may be made without the permission of the Librarian of the University of Otago. August 2010 Parents, Siblings and Pacifism: The Baxter Family and Others (World War One and World War Two) Belinda C. Cumming Presented in partial fulfilment for the requirements for the degree of BA (Hons) in History, at the University of Otago, 2007 Table of Contents List of Abbreviations u List of Illustrations 111 Introduction 1 Chapter One: A Family Commitment 6 Chapter Two: A Family Inheritance 23 Chapter Three: Source of Pride or Shame? Families Pay the Price for Pacifism 44 Conclusion 59 Afterword 61 Bibliography 69 List of Abbreviations CPS Christian Pacifist Society CWI Canterbury Women's Institute ICOM International Conscientious Objectors' Meeting PAW Peace Action Wellington PPU Peace Pledge Union RSA Returned Services Association WA-CL Women's Anti-Conscription League WIL Women's International Peace League WRI War Resisters International 11 List of Illustrations Figure 1. John Baxter Figure 2. Military Service Act, 1916 Figure 3. -

These Strange Criminals: an Anthology Of

‘THESE STRANGE CRIMINALS’: AN ANTHOLOGY OF PRISON MEMOIRS BY CONSCIENTIOUS OBJECTORS FROM THE GREAT WAR TO THE COLD WAR In many modern wars, there have been those who have chosen not to fight. Be it for religious or moral reasons, some men and women have found no justification for breaking their conscientious objection to vio- lence. In many cases, this objection has lead to severe punishment at the hands of their own governments, usually lengthy prison terms. Peter Brock brings the voices of imprisoned conscientious objectors to the fore in ‘These Strange Criminals.’ This important and thought-provoking anthology consists of thirty prison memoirs by conscientious objectors to military service, drawn from the United Kingdom, the United States, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand, and centring on their jail experiences during the First and Second World Wars and the Cold War. Voices from history – like those of Stephen Hobhouse, Dame Kathleen Lonsdale, Ian Hamilton, Alfred Hassler, and Donald Wetzel – come alive, detailing the impact of prison life and offering unique perspectives on wartime government policies of conscription and imprisonment. Sometimes intensely mov- ing, and often inspiring, these memoirs show that in some cases, indi- vidual conscientious objectors – many well-educated and politically aware – sought to reform the penal system from within either by publicizing its dysfunction or through further resistance to authority. The collection is an essential contribution to our understanding of criminology and the history of pacifism, and represents a valuable addition to prison literature. peter brock is a professor emeritus in the Department of History at the University of Toronto. -

The Principal Time Balls of New Zealand

Journal of Astronomical History and Heritage, 20(1), 69±94 (2017). THE PRINCIPAL TIME BALLS OF NEW ZEALAND Roger Kinns School of Mechanical and Manufacturing Engineering, University of New South Wales, Sydney, NSW 2052, Australia. Email: [email protected] Abstract: Accurate time signals in New Zealand were important for navigation in the Pacific. Time balls at Wellington and Lyttelton were noted in the 1880 Admiralty list of time signals, with later addition of Otago. The time ball service at Wellington started in March 1864 using the first official observatory in New Zealand, but there was no Wellington time ball service during a long period of waterfront redevelopment during the 1880s. The time ball service restarted in November 1888 at a different harbour location. The original mechanical apparatus was used with a new ball, but the system was destroyed by fire in March 1909 and was never replaced. Instead, a time light service was inaugurated in 1912. The service at Lyttelton, near Christchurch, began in December 1876 after construction of the signal station there. It used telegraph signals from Wellington to regulate the time ball. By the end of 1909, it was the only official time ball in New Zealand, providing a service that lasted until 1934. The Lyttelton time ball tower was an iconic landmark in New Zealand that had been carefully restored. Tragically, the tower collapsed in the 2011 earthquakes and aftershocks that devastated Christchurch. An Otago daily time ball service at Port Chalmers, near Dunedin, started in June 1867, initially using local observatory facilities. The service appears to have been discontinued in October 1877, but was re-established in April 1882 as a weekly service, with control by telegraph from Wellington. -

The Consequences and Later Life the Military Service Act 1916 Did Not Recognise the Stand Taken by the Baxter Brothers, As the O

The Consequences and Later Life Contemporary illustration of Field Punishment Number One. The Military Service Act 1916 did not recognise the stand taken by the Baxter Brothers, as the only grounds for a man to claim conscientious objection were: That he was on the fourth day of August, nineteen hundred and fourteen, and has since continuously been a member of a religious body the tenets and doctrines of which religious body declare the bearing of arms and the performance of any combatant service to be contrary to Divine revelation, and also that according to his own conscientious religious belief the bearing of arms and the performance of any combatant service is unlawful by reason of being contrary to Divine revelation. This was a considerable contraction of the exemption allowed under the Defence Amendment Act 1912, which had provided under Section 65(2): On the application of any person a Magistrate may grant to the applicant a certificate of exemption from military training and service if the Magistrate is satisfied that the applicant objects in good faith to such training and service on the ground that it is contrary to his religious belief. The 1916 Act meant that only Christadelphians, Seventh-day Adventists, and Quakers were to be recognised as conscientious objectors. As Baxter was not a member of one of these, he could not apply for objector status. According to the Act, Baxter was automatically deemed to be a First Division Reservist. Failure to report for duty became either desertion or absence without leave, offences under the Army Act. Baxter and two of his brothers – Alexander and John – were arrested by civilian police in early 1917 for failing to comply with the Act and delivered directly to Trentham Military Camp. -

“To Leaven the Lump”: a Critical History of the Anglican Pacifist Fellowship in New Zealand

“To Leaven the Lump”: A Critical History of the Anglican Pacifist Fellowship in New Zealand By Zane Mather A Thesis submitted to the Victoria University of Wellington in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Masters of Arts in Religious Studies Victoria University of Wellington 2011 ABSTRACT This thesis is an interpretation of the history and character of the Anglican Pacifist Fellowship in New Zealand (NZAPF). It focuses on accounting for the limited growth and influence of the Fellowship upon New Zealand’s largest Christian denomination, and on the continuing marginality of the pacifist position. Throughout its history, the organisation has sought to convince others within the Anglican Church that an absolutist, politically engaged and non-anarchistic pacifism is the truest Christian response to the problem of modern warfare. This has been attempted primarily through efforts at education aimed at both clergy and laity. The thesis argues that the NZAPF has been characterised by a commitment to absolute doctrinaire pacifism, despite ongoing tensions between this position and more pragmatic considerations. Overall, the NZAPF attracted only a small group of members throughout its history, and it exerted a limited demonstrable influence on the Anglican Church. This thesis analyses the reasons for this, focusing especially on those factors which arose from the nature of the NZAPF itself, the character of its pacifism, and the relationship between the NZAPF and its primary target audience, the Anglican Church in New Zealand. The research is based on literature and correspondence from the NZAPF as well as personal communication with extant members, where this was feasible. -

Name Suburb Notes a Abbotleigh Avenue Te Atatu Peninsula Named C.1957. Houses Built 1957. Source: Geomaps Aerial Photo 1959

Name Suburb Notes A Abbotleigh Avenue Te Atatu Peninsula Named c.1957. Houses built 1957. Source: Geomaps aerial photo 1959. Abel Tasman Ave Henderson Named 7/8/1973. Originally named Tasman Ave. Name changed to avoid confusion with four other Auckland streets. Abel Janszoon Tasman (1603-1659) was a Dutch navigator credited with being the discoverer of NZ in 1642. Located off Lincoln Rd. Access Road Kumeu Named between 1975-1991. Achilles Street New Lynn Named between 1943 and 1961. H.M.S. Achilles ship. Previously Rewa Rewa Street before 1930. From 1 March 1969 it became Hugh Brown Drive. Acmena Ave Waikumete Cemetery Named between 1991-2008. Adam Sunde Place Glen Eden West Houses built 1983. Addison Drive Glendene Houses built 1969. Off Hepburn Rd. Aditi Close Massey Formed 2006. Previously bush in 2001. Source: Geomaps aerial photo 2006. Adriatic Avenue Henderson Named c.1958. Geomaps aerial photo 1959. Subdivision of Adriatic Vineyard, which occupied 15 acres from corner of McLeod and Gt Nth Rd. The Adriatic is the long arm of the Mediterranean Sea which separates Italy from Yugoslavia and Albania. Aetna Place McLaren Park Named between 1975-1983. Located off Heremaia St. Subdivision of Public Vineyard. Source: Geomaps aerial photo 1959. Afton Place Ranui Houses built 1979. Agathis Rise Waikumete Cemetery Named between 1991-2008. Agathis australis is NZ kauri Ahu Ahu Track Karekare Named before 2014. The track runs from a bend in Te Ahu Ahu Road just before the A- frame house. The track follows the old bridle path on a steeply graded descent to Watchman Road. -

12. New Zealand War Correspondence Before 1915

12. New Zealand war correspondence before 1915 ABSTRACT Little research has been published on New Zealand war correspondence but an assertion has been made in a reputable military book that the country has not established a strong tradition in this genre. To test this claim, the author has made a preliminary examination of war correspondence prior to 1915 (when New Zealand's first official war correspondent was appointed) to throw some light on its early development. Because there is little existing research in this area much of the information for this study comes from contemporary newspaper reports. In the years before the appointment of Malcolm Ross as the nation's official war correspondent. New Zealand newspapers clearly saw the importance of reporting on war, whether within the country or abroad and not always when it involved New Zealand troops. Despite the heavy cost to newspapers, joumalists were sent around the country and overseas to cover confiiets. Two types of war correspondent are observable in those early years—the soldier joumalist and the ordinary joumalist plucked from his newsroom or from his freelance work. In both cases one could call them amateur war correspondents. Keywords: conflict reporting, freelance joumaiism, war correspondents, war reporting ALLISON OOSTERMAN AUT University, Auckland HIS ARTICLE is a brief introduction to New Zealand war correspondence prior to 1915 when the first official war correspon- Tdent was appointed by the govemment. The aim was to conduct a preliminary exploration ofthe suggestion, made in The Oxford Companion to New Zealand military history (hereafter The Oxford Companion), that New Zealand has not established a strong tradition of war correspondence (McGibbon, 2000, p. -

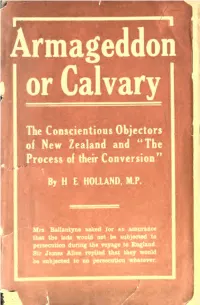

Armageddon Or Calvary : the Conscientious Objectors of New

The Conscientious Objectors of New Zealand and "The Process of their Conversion" By H E HOLLAND, M.P. ' Mrs Ballantyne asked for an assurance that the lads would not be subjected to persecution during the voyage to England. Sir James Allen replied that they would be subjected to no persecution whatever. Digitized by tine Internet Arciiive in 2007 witii funding from IVIicrosoft Corporation littp://www.arcliive.org/details/armageddonorcalvOOIiolliala p ^uj; %'/i 3 1822 02466 4732 ARMAGEDDON OR CALVARY THE CONSCIENTIOUS OBJECTORS of New Zealand and "The Process " of their Conversion By H. E. HOLLAND. M.P. n WELLINGTIN. N.Z. :; P:- '•:r.' B. Thj- }/:^o-vr.\.\-A:- Wopr;=^s Pp:N^i-;:- and Pi'e;.:5h;v- j, Co. Ltp. AND P-jB;,;c>H^i - H E. Ho:.!.\N' . 207 Ha-:-> Valley Roao. Brooklyn — —, THE C.O's. Their names are writ in every Clink This small but steadfast band Who for themselves have dared to think And firmly take their stand. The tyrants' boast to crush and kill And this proud spirit bend Does only strengthen each man's will To conquer in the end. Although to-night in prison cell 'Neath Mammon's lock and key, It only holds the earthly shell The mind and soul are free. The Brotherhood of Man's their aim ; So come whate'er betide They'll bear it all m Freedom's name, Their conscience is their guide. Though each should fill a Martyr's grave, What grander end could be ? Their death will only help to pave The road to Liberty.