TF Years 11-13 Truth and Fiction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Dunedin Lawyer's Seed of Dissent: A.R. Barclay, the Boer War and The

1 The Dunedin lawyer’s seed of dissent: A.R. Barclay, the Boer war and the socialist origins of Archibald Baxter’s pacifism 1. Introduction: the case for a consideration of the socialist aspect of Baxter’s pacifism Archibald Baxter’s ‘We Will Not Cease’ is an iconic and rightfully famous pacifist statement. Narrated in a lucid and unadorned style, Baxter’s story exposes the horrors and hypocrisy of war. It is also a memoir of courage and resistance, in which a humble farmer from Otago is pitted against the military authorities of an Empire. As Steven Loveridge points out, the ‘success of the text owes much to its narration and the imparted impression of Baxter’s strength of character against hostile circumstances1.’ Baxter’s moral character is tenderly recalled by his wife Millicent, who picks out her son’s poem ‘To My Father’ as her favourite poem, and cites this moving verse: …. I have loved You more than my own good, because you stand For country pride and gentleness, engraved In forehead lines, veins swollen on the hand; Also, behind slow speech and quiet eye The rock of passionate integrity2. 1 Loveridge, S. ‘Calls To Arms: New Zealand Society and Commitment to the Great War’. VUP. Wellington, 2014. p. 167 2 Baxter, M. ‘The Memoirs of Millicent Baxter’. Cape Catley, 1981. p.110 2 This verse is a brilliant and moving summary of the moral qualities of Archibald Baxter, which appear to be intimately wedded to the land itself. We think of the resolute and immensely strong will of Baxter resisting the pressure to fight as a soldier in the trenches of WW1 – the ‘rock of passionate integrity’. -

Unsung Heroes Clay Nelson © 26 April 2015 Auckland Unitarian Church

Unsung Heroes Clay Nelson © 26 April 2015 Auckland Unitarian Church It was December 1, 1969. A day I remember well. It was during my third year of university. My roommates and I were gathered around the radio as was every American male born between 1946 and 1950. It was the first draft lottery. For each day of the year one of 366 numbers would be drawn. If a number lower than 195 was assigned to your birthday it meant you would be conscripted in the next year or as soon as your student deferment ended to fight in an unpopular war in Southeast Asia. My roommate, who was also destined to become a minister one day, and I had both applied for Conscientious Objector status. Not being from traditionally pacifist churches such as the Quakers, Brethren and Seventh Day Adventists our chances were not good. My roommate’s number was 128; mine was 313. It was a day of muted relief for me, for although I was in the clear, he was not. My only regret was that I would never learn if I could have convinced the draft board to grant me CO status. To apply for CO status was for me not done lightly or easily. I was not raised in a pacifist family. My father enlisted in World War II, lying about his age to do so. He was conscripted during the Korean War, but was struck down with polio shortly after being inducted. My church did not teach pacifist principles and was closely associated with the power of the state. -

August 2010 PROTECTION of AUTHOR ' S C O P Y R I G H T This

THE UNIVERSITY LIBRARY PROTECTION OF AUTHOR ’S COPYRIGHT This copy has been supplied by the Library of the University of Otago on the understanding that the following conditions will be observed: 1. To comply with s56 of the Copyright Act 1994 [NZ], this thesis copy must only be used for the purposes of research or private study. 2. The author's permission must be obtained before any material in the thesis is reproduced, unless such reproduction falls within the fair dealing guidelines of the Copyright Act 1994. Due acknowledgement must be made to the author in any citation. 3. No further copies may be made without the permission of the Librarian of the University of Otago. August 2010 Parents, Siblings and Pacifism: The Baxter Family and Others (World War One and World War Two) Belinda C. Cumming Presented in partial fulfilment for the requirements for the degree of BA (Hons) in History, at the University of Otago, 2007 Table of Contents List of Abbreviations u List of Illustrations 111 Introduction 1 Chapter One: A Family Commitment 6 Chapter Two: A Family Inheritance 23 Chapter Three: Source of Pride or Shame? Families Pay the Price for Pacifism 44 Conclusion 59 Afterword 61 Bibliography 69 List of Abbreviations CPS Christian Pacifist Society CWI Canterbury Women's Institute ICOM International Conscientious Objectors' Meeting PAW Peace Action Wellington PPU Peace Pledge Union RSA Returned Services Association WA-CL Women's Anti-Conscription League WIL Women's International Peace League WRI War Resisters International 11 List of Illustrations Figure 1. John Baxter Figure 2. Military Service Act, 1916 Figure 3. -

These Strange Criminals: an Anthology Of

‘THESE STRANGE CRIMINALS’: AN ANTHOLOGY OF PRISON MEMOIRS BY CONSCIENTIOUS OBJECTORS FROM THE GREAT WAR TO THE COLD WAR In many modern wars, there have been those who have chosen not to fight. Be it for religious or moral reasons, some men and women have found no justification for breaking their conscientious objection to vio- lence. In many cases, this objection has lead to severe punishment at the hands of their own governments, usually lengthy prison terms. Peter Brock brings the voices of imprisoned conscientious objectors to the fore in ‘These Strange Criminals.’ This important and thought-provoking anthology consists of thirty prison memoirs by conscientious objectors to military service, drawn from the United Kingdom, the United States, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand, and centring on their jail experiences during the First and Second World Wars and the Cold War. Voices from history – like those of Stephen Hobhouse, Dame Kathleen Lonsdale, Ian Hamilton, Alfred Hassler, and Donald Wetzel – come alive, detailing the impact of prison life and offering unique perspectives on wartime government policies of conscription and imprisonment. Sometimes intensely mov- ing, and often inspiring, these memoirs show that in some cases, indi- vidual conscientious objectors – many well-educated and politically aware – sought to reform the penal system from within either by publicizing its dysfunction or through further resistance to authority. The collection is an essential contribution to our understanding of criminology and the history of pacifism, and represents a valuable addition to prison literature. peter brock is a professor emeritus in the Department of History at the University of Toronto. -

The Consequences and Later Life the Military Service Act 1916 Did Not Recognise the Stand Taken by the Baxter Brothers, As the O

The Consequences and Later Life Contemporary illustration of Field Punishment Number One. The Military Service Act 1916 did not recognise the stand taken by the Baxter Brothers, as the only grounds for a man to claim conscientious objection were: That he was on the fourth day of August, nineteen hundred and fourteen, and has since continuously been a member of a religious body the tenets and doctrines of which religious body declare the bearing of arms and the performance of any combatant service to be contrary to Divine revelation, and also that according to his own conscientious religious belief the bearing of arms and the performance of any combatant service is unlawful by reason of being contrary to Divine revelation. This was a considerable contraction of the exemption allowed under the Defence Amendment Act 1912, which had provided under Section 65(2): On the application of any person a Magistrate may grant to the applicant a certificate of exemption from military training and service if the Magistrate is satisfied that the applicant objects in good faith to such training and service on the ground that it is contrary to his religious belief. The 1916 Act meant that only Christadelphians, Seventh-day Adventists, and Quakers were to be recognised as conscientious objectors. As Baxter was not a member of one of these, he could not apply for objector status. According to the Act, Baxter was automatically deemed to be a First Division Reservist. Failure to report for duty became either desertion or absence without leave, offences under the Army Act. Baxter and two of his brothers – Alexander and John – were arrested by civilian police in early 1917 for failing to comply with the Act and delivered directly to Trentham Military Camp. -

“To Leaven the Lump”: a Critical History of the Anglican Pacifist Fellowship in New Zealand

“To Leaven the Lump”: A Critical History of the Anglican Pacifist Fellowship in New Zealand By Zane Mather A Thesis submitted to the Victoria University of Wellington in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Masters of Arts in Religious Studies Victoria University of Wellington 2011 ABSTRACT This thesis is an interpretation of the history and character of the Anglican Pacifist Fellowship in New Zealand (NZAPF). It focuses on accounting for the limited growth and influence of the Fellowship upon New Zealand’s largest Christian denomination, and on the continuing marginality of the pacifist position. Throughout its history, the organisation has sought to convince others within the Anglican Church that an absolutist, politically engaged and non-anarchistic pacifism is the truest Christian response to the problem of modern warfare. This has been attempted primarily through efforts at education aimed at both clergy and laity. The thesis argues that the NZAPF has been characterised by a commitment to absolute doctrinaire pacifism, despite ongoing tensions between this position and more pragmatic considerations. Overall, the NZAPF attracted only a small group of members throughout its history, and it exerted a limited demonstrable influence on the Anglican Church. This thesis analyses the reasons for this, focusing especially on those factors which arose from the nature of the NZAPF itself, the character of its pacifism, and the relationship between the NZAPF and its primary target audience, the Anglican Church in New Zealand. The research is based on literature and correspondence from the NZAPF as well as personal communication with extant members, where this was feasible. -

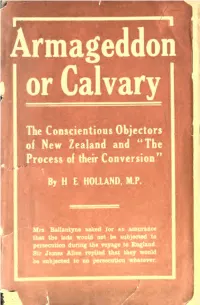

Armageddon Or Calvary : the Conscientious Objectors of New

The Conscientious Objectors of New Zealand and "The Process of their Conversion" By H E HOLLAND, M.P. ' Mrs Ballantyne asked for an assurance that the lads would not be subjected to persecution during the voyage to England. Sir James Allen replied that they would be subjected to no persecution whatever. Digitized by tine Internet Arciiive in 2007 witii funding from IVIicrosoft Corporation littp://www.arcliive.org/details/armageddonorcalvOOIiolliala p ^uj; %'/i 3 1822 02466 4732 ARMAGEDDON OR CALVARY THE CONSCIENTIOUS OBJECTORS of New Zealand and "The Process " of their Conversion By H. E. HOLLAND. M.P. n WELLINGTIN. N.Z. :; P:- '•:r.' B. Thj- }/:^o-vr.\.\-A:- Wopr;=^s Pp:N^i-;:- and Pi'e;.:5h;v- j, Co. Ltp. AND P-jB;,;c>H^i - H E. Ho:.!.\N' . 207 Ha-:-> Valley Roao. Brooklyn — —, THE C.O's. Their names are writ in every Clink This small but steadfast band Who for themselves have dared to think And firmly take their stand. The tyrants' boast to crush and kill And this proud spirit bend Does only strengthen each man's will To conquer in the end. Although to-night in prison cell 'Neath Mammon's lock and key, It only holds the earthly shell The mind and soul are free. The Brotherhood of Man's their aim ; So come whate'er betide They'll bear it all m Freedom's name, Their conscience is their guide. Though each should fill a Martyr's grave, What grander end could be ? Their death will only help to pave The road to Liberty. -

The Poetry and Prose of Archibald and James K. Baxter

THE POEJRY AND PROSE OF ARCHIBALD AND JAMES K. BAXTER: LIKE FATHER, LIKE SON? A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in English in the University of Canterbury by Jennifer C. Johnston University of Canterbury 2001 The Poetry and Prose of Archibald and James K. Baxter: Like Father, Like Son? Jennifer Johnston PR 95'81 , D. 7 I~" '.<' 1::> J.;'.,) . J 7:2 Dt Contents Acknowledgements ... .................. '" ... ... ... ... ... ... .... 1 Abstract... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... .. ... ... ... 11 Introduction ... ..... , '" ............................. , ... ... ... .... 1 Chapter 1 Archie Baxter: The Man with the Iron Will ... ,. ... ..... 7 Chapter 2 Archie Baxter: Brother Bard........................ ........ 26 Chapter 3 James K. Baxter: Following in the Footsteps... ... ... ... 52 Chapter 4 The Legendary Baxters... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... 96 Chapter 5 The Mythological Horse ... ......... '" ... ... ... ... ... ... ...... 119 Conclusion ... ................................................... '" 138 Appendix I Poems by Archibald Baxter .......................... ,....... 144 Appendix II Poems by James K. Baxter... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... .. 160 Selected Bibliography ... ....... , ........ " '" ", ... __ .... I ••• ,.. 186 -'7 JUN ZOOZ Acknowledgements I would like to thank the following people who helped make this project possi,:, ble. Firstly, thanks to my Supervisor Dr. Rob Jackaman of the English Depart ment -

Options and Opportunities for New Zealand and France 1918-1935

Copyright is owned by the Author of the thesis. Permission is given for a copy to be downloaded by an individual for the purpose of research and private study only. The thesis may not be reproduced elsewhere without the permission of the Author. OPTIONS AND OPPORTUNITIES FOR NEW ZEALAND AND FRANCE 1918-1935 : Les Liaisons dangereuses? A THESIS PRESENTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN HISTORY AT MASSEY UNIVERSITY, ALBANY, NEW ZEALAND. ALISTAIR CLIVE WATTS 2019 2 Abstract The New Zealand histories typically assert that a new national identity evolved after World War I to substitute for the pre-war British-based model. This assumption has resulted in the creation of a British-centric historiography that understates the important role of other non-British influencers - especially the French – in the evolution of post-war New Zealand. Systematic sampling of newspaper articles in the PapersPast database has revealed that within New Zealand’s post-1918 public discourse there was a diverse seam of opinion and news related to France that sat alongside that from Britain. This suggests that events concerning France were more prevalent in shaping the New Zealand story than the earlier histories have indicated. These additional perspectives have been integrated into aspects of the New Zealand post-World War I narrative, supplemented where appropriate with articles from French newspapers and the archive. When the First World War finally ended, New Zealand attempted to disengage from Europe in order to put the collective national trauma in the past. Resuming the traditional dislike of the French was a reflexive rejection of the war years rather than a considered policy. -

The Conscription Issue in Australia and New Zealand, 1916–17

Similar, Yet Different: The Conscription Issue in Australia and New Zealand, 1916–17 JOAN BEAUMONT Abstract Australia and New Zealand came to World War One with similar political trajectories, and their experience and memory of the war had much in common. However, on the key issue of conscription for overseas military service, they diverged. This article considers possible explanations for this difference. As others have noted, whereas New Zealand Prime Minister William Massey could be confident of a parliamentary majority, the early political power of the labour movement in Australia forced his Australian counterpart, W. M. Hughes, to take conscription to a popular vote—a forum in which the performance of politics and dissent took an unpredictable form. Beyond this, Hughes’s chances of gaining consent for conscription were compromised by the timing of the conscription campaigns in Australia—some critical months later than in New Zealand—his personal political style and his failure to craft a scheme of conscription that could secure the majority consent that the more adroit Massey achieved in New Zealand. The Australian commemoration of the centenary of World War One from 2014–18 focused largely on battles. In particular, prominence was given to those battles where Australians were the victims of poor leadership and command (such as Gallipoli and Fromelles), or in which they supposedly made a major contribution to Allied victory over the Central Powers (Villers- Bretonneux and Amiens). Generally, less public attention was paid to those events on the home front that were arguably of greater importance in Australian political history: the two referenda about conscription for overseas service held in October 1916 and December 2017. -

National Centre for Peace and Conflict Studies Newsletter DECEMBER 2014

National Centre for Peace and Conflict Studies newsletter DeCeMBer 2014 Welcome from the Director The National Centre for Peace and Conflict Finally, I facilitated the third in a series of In thIs Issue: Studies came through its first five year University interactive problem solving workshops between Review with flying colours. A highly qualified academic and political influentials from China, Welcome from the Director panel of national and international experts met Japan and Korea. The meeting in Yokohama, for three days, charged with assessing the quality, Japan, focused on ways in which political leaders Richard Falk visits depth, significance and impact of our teaching, from all three countries might understand research and practice programmes over the and address painful collective memories, stop Tribute to Andrea Derbidge last quinquennium. xenophobic nationalism and deal with territorial Profile: Liesel Mitchell The initial verbal feedback from the panel was disputes nonviolently and creatively. This excellent, with strong acknowledgement and workshop is an example of the practice work that Archibald Baxter Memorial approval our achievements to date and support we wish to develop in the future. Trust launched for our aspirational goals for the next five 2014 has been an extremely busy and productive Peacemaker of the Year years. The panel’s report will make a range of year for the Centre. We welcomed our first Master recommendations for the Centre to consider of Peace and Conflict Studies class. We graduated Major Marsden grant won and implement. 4 new Ph.D students and 6 MA by thesis. We I am enormously proud of the wisdom and now have a faculty of six tenured positions. -

The Military Service Boards' Operations in The

Copyright is owned by the Author of the thesis. Permission is given for a copy to be downloaded by an individual for the purpose of research and private study only. The thesis may not be reproduced elsewhere without the permission of the Author. ‘Should He Serve?’ The Military Service Boards’ Operations in the Wellington Provincial District, 1916-1918 A thesis presented in partial fulfilment of the requirement for the degree of Master of Arts in History at Massey University David Littlewood 2010 Contents Page No. Abbreviations iii Map Boundaries of North Island Provincial Districts in 1921 iv Charts v Acknowledgements vi Introduction 1 Chapter One Setting the Parameters: 10 Government Decisions prior to the Boards’ Operations Chapter Two Keeping a Tight Rein: 26 Government Direction during the Boards’ Operations Chapter Three Equality of Sacrifice: 43 The Attitudes of the Board Members Chapter Four Reality or Pragmatism?: 55 The Attitudes of the Appellants Chapter Five Assessment over Hostility: 75 The Treatment of Conscientious Objectors Chapter Six Firm but Fair: 90 The Boards’ Verdicts Conclusions 104 Appendix Definition of Occupational Classifications Used 108 Bibliography 110 ii Abbreviations AD Army Department AP Sir James Allen Papers AJHR Appendices to the Journals of the House of Representatives EP Evening Post FS Feilding Star MES Manawatu Evening Standard MP Member of Parliament NEB National Efficiency Board NZG New Zealand Gazette NZH New Zealand Herald NZS New Zealand Statutes NZT New Zealand Times NZPD New Zealand Parliamentary Debates PH Pahiatua Herald WDT Wairarapa Daily Times WC Wanganui Chronicle iii Boundaries of North Island Provincial Districts in 1921 Source: 1921 Census.