The Blank at the Bottom: Risk and Repetition in Mountain Literature

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Summits of Modern Man: Mountaineering After the Enlightenment (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2013)

Bibliography Peter H. Hansen, The Summits of Modern Man: Mountaineering after the Enlightenment (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2013) This bibliography consists of works cited in The Summits of Modern Man along with a few references to citations that were cut during editing. It does not include archival sources, which are cited in the notes. A bibliography of works consulted (printed or archival) would be even longer and more cumbersome. The print and ebook editions of The Summits of Modern Man do not include a bibliography in accordance with Harvard University Press conventions. Instead, this online bibliography provides links to online resources. For books, Worldcat opens the collections of thousands of libraries and Harvard HOLLIS records often provide richer bibliographical detail. For articles, entries include Digital Object Identifiers (doi) or stable links to online editions when available. Some older journals or newspapers have excellent, freely-available online archives (for examples, see Journal de Genève, Gazette de Lausanne, or La Stampa, and Gallica for French newspapers or ANNO for Austrian newspapers). Many publications still require personal or institutional subscriptions to databases such as LexisNexis or Factiva for access to back issues, and those were essential resources. Similarly, many newspapers or books otherwise in the public domain can be found in subscription databases. This bibliography avoids links to such databases except when unavoidable (such as JSTOR or the publishers of many scholarly journals). Where possible, entries include links to full-text in freely-accessible resources such as Europeana, Gallica, Google Books, Hathi Trust, Internet Archive, World Digital Library, or similar digital libraries and archives. -

Pour Les Guides

VOIE ROYALE POUR LES GUIDES L’histoire de la compagnie des guides de Saint-Gervais Le 8 août 1786 sonne la fin des espérances locales. est étroitement liée à l’exploration du massif du Mont- Michel Paccard et le guide Jacques Balmat Blanc et à la rivalité avec les communes voisines. atteignent le sommet du mont Blanc depuis Fondée en 1864, elle est la deuxième institution de Chamonix. La voie du Goûter va tomber dans guides de haute montagne en France. Avec quelques l’oubli pendant de nombreuses années. Charles singularités qui la distinguent de ses voisines. Durier, qui fut président et secrétaire général du Club alpin français à partir de 1895, écrira : u xviiie siècle, les tentatives « Chamonix et Saint-Gervais sont deux cités d’ascension du mont Blanc rivales, comme autrefois Rome et Albe. Si la pre- font entrer Saint-Gervais mière comptait les cristalliers les plus hardis, la dans l’histoire de l’alpinisme. seconde était fière à bon droit de l’intrépidité de La conquête de la plus haute ses chasseurs de chamois. C’est par le côté de cime des Alpes ne laisse pas Saint-Gervais que l’ascension du Mont-Blanc avait indifférents les habitants du d’abord paru plus près de réussir… Saint-Gervais pays. Ces paysans, conscients crut tenir la victoire, Chamonix l’emporta et Saint- des retombées économiques potentielles de l’alpi- Gervais en conçut un amer chagrin. » Ascension du mont Blanc La première ascension saint-gervolaine du mont ceux de Chamonix. Elle se dote d’un fonctionnement nisme, vont troquer leurs outils agricoles contre le En 1815, le colonel autrichien Franz-Ludwig von par le pyrénéiste et alpiniste Blanc est réalisée par le chef des guides Joseph- moderne reposant sur la « caisse de secours » (un français Henri Brulle, piolet pour accompagner les premiers voyageurs. -

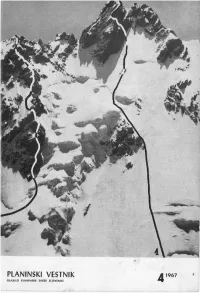

PV 1967 04.Pdf

poštnina plačana v gotovini VSEBINA: RAZMIŠLJANJA OB NAŠIH ODPRAVAH V KAVKAZ Ing. Pavle Šegula 145 KAVKAZ - MOST MED ALPAMI IN HIMALAJO EMO Janez Krušic 149 SLOVENSKO REBRO V SEVERNI STENI GESTOLE Celje Janez Krušic 157 SLOVENSKI STEBER V ULLU-AUSU Ing. Drago Zagorc 160 TIMOFEJEVA SMER V MIŽIRGIJU EMAJLIRNICA Janez Golob 161 METALNA INDUSTRIJA KAKO SE JE CVET SLOVENSKIH ALPINISTOV PRIVAJAL NA VIŠINO 5145 METROV ORODJARNA Boris Krivic 164 NJEGOV ZADNJI VZPON A. Kopinšek 168 IZDELUJE IN DOBAVLJA: K DISKUSIJI O NEKATERIH KRAŠKIH OBLIKAH VISO- KOGORSKEGA KRASA — frite z dodatki za izdelavo emajlov Dušan Novak 169 — emajlirano, pocinkano in alu posodo, sanitarno SEDEM DESETLETIJ PLANINSKEGA VESTNIKA in gospodinjsko opremo ter kovinsko embalažo (1895-1965) — toplotne naprave: radiatorje in kotle za cen- Evgen Lovšin 174 tralno in etažno ogrevanje GOZD JE NAŠ DOM 180 — odpreske in kolesa za motorna vozila ter od- DRUŠTVENE NOVICE 183 preske za rudarstvo ALPINISTIČNE NOVICE 184 — vse vrste orodij zo serijsko proizvodnjo: rezilna, IZ PLANINSKE LITERATURE 187 izsekovalna, vlečna, kombinirana in upogibna RAZGLED PO SVETU 188 orodja za predelavo pločevine, orodja za tlačni ANICA KUK liv in za proizvodnjo iz plastičnih mas, stekla Stanislav Gilič 191 in keramike NASLOVNA STRAN: — emajlira, pocinkuje in predeluje pločevine SEVERNO OSTENJE ULLU-AUS (4789 m) 1 - DIREKTNA SMER V SEVERNI STENI Tel.: 39-21 - Telegram: EMO-Celje - Telex: 0335-12 2 - SLOVENSKI STEBER - PRVENSTVENA SMER SEDEŽ: LJUBLJANA - VEVČE USTANOVLJENE LETA 1842 IZDELUJEJO SULFITNO CELULOZO I. a za vse vrste papirja PINOTAN - strojilni ekstrat BREZLESNI PAPIR za grafično in predelovalno in- dustrijo: za reprezentativne izdaje, umetniške slike, propagandne in turistične prospekte, za pisemski papir in kuverte najboljše kvalitete, za razne protokole, matične knjige, obrazce, -Planinski Vestnik« je glasilo Planinske zveze Slovenije / šolske zvezke in podobno Izdaja ga PZS - urejuje ga uredniški odbor. -

Heinrich Parler

Heinrich Parler Heinrich Parler the Elder (also Heinrich of Gmünd; German: Heinrich von Gemünd der Ältere; born between 1300 and 1310 â“ circa 1370), was a German architect and master builder of the Gothic period. Heinrich Parler was probably born in Cologne between 1300 and 1310, but later lived and worked in Gmünd, an Imperial City (German: Reichsstädte) of the Holy Roman Empire.[2] He became construction manager of Holy Cross Minster in Gmünd between 1325 and 1330. Heinrich Harrer (German pronunciation: [ˈhaɪnÊɪç ˈhaÊÉ]; 6 July 1912 â“ 7 January 2006) was an Austrian mountaineer, sportsman, geographer, and author. He is best known for being on the four-man climbing team that made the first ascent of the North Face of the Eiger in Switzerland, and for his books Seven Years in Tibet (1952) and The White Spider (1959). Heinrich Harrer was born 6 July 1912 in Hüttenberg, Austria, in the district of Sankt Veit an der Glan in the state of Carinthia. His father was a Heinrich Parler the Elder (also Heinrich of Gmünd, German: Heinrich von Gemünd der Ältere; c. 1310 â“ c. 1370), was a German architect and sculptor. His masterpiece is Holy Cross Minster, an influential milestone of late Gothic architecture in the town of Schwäbisch Gmünd, Baden- Württemberg, Germany. Parler also founded the Parler family of master builders and his descendants worked in various parts of central Europe, especially Bohemia. His son, Peter Parler, became one of the major architects of the Heinrich Harrer was an Austrian mountaineer who was part of the team that made the first ascent of the formidable north wall of the Eiger in Switzerland. -

In Memoriam I Met Ralph in 1989 When I Moved to Wolverhampton, Through Our Involvement with the Wolverhampton Mountain- Eering Club

Obituaries Matterhorn. Edward Theodore Compton. 1880. Watercolour. 43 x 68cm. (Alpine Club Collection HE118P) 399 I N M E M ORI am 401 Ralph Atkinson 1952 - 2014 In Memoriam I met Ralph in 1989 when I moved to Wolverhampton, through our involvement with the Wolverhampton Mountain- eering Club. Weekends in Wales The Alpine Club Obituary Year of Election and day trips to Matlock and the (including to ACG) Roaches became the foundation for extended expeditions to the Ralph Atkinson 1997 Alps including, in 1991, a fine Una Bishop 1982 six-day ski traverse of the Haute John Chadwick 1978 Route, Argentière to Zermatt, John Clegg 1955 and ascents in 1993 of the Mönch Dennis Davis 1977 and Jungfrau. Descending the Gordon Gadsby 1985 Jungfrau in a storm, we could Johannes Villiers de Graaff 1953 barely see each other. I slipped David Jamieson 1999 in the new snow and had to self- Emlyn Jones 1944 arrest, aided by the tension in the Brian ‘Ned’ Kelly 1968 rope to Ralph. It worked, and I Neil Mackenzie Asp.2011, 2015 Ralph Atkinson climbing on the slabs of Fournel, was soon back on the ridge, but Richard Morgan 1960 near Argentière, Ecrins. (Andy Clarke) when we dropped below the John Peacock 1966 Rottalsattel and could speak to Bill Putnam 1972 each other again, he had no idea that anything untoward had happened. Stephanie Roberts 2011 I recall long journeys by car enlivened by his wide-ranging taste in music. Les Swindin 1979 The keynote of many outings was his sense of fun. There were long stories, John Tyson 1952 jokes or pithy one-liners. -

In Memoriam 1936 - 2016 Mike Was Born in Mumbai

Obituaries Tsering, Street trader, Kathmandu. Rob Fairley, 2000. (Watercolour. 28cm x 20cm. Sketchbook drawing.) 363 I N M E M ORI am 365 Mike Binnie In Memoriam 1936 - 2016 Mike was born in Mumbai. He lived there for nine years until he went to prep school in Scotland. From there, he went on to Uppingham School, and then to Keble College, Oxford, The Alpine Club Obituary Year of Election to read law. While at Keble, Mike (including to ACG) joined its climbing club and was also an active member of the OUMC, Mike Binnie 1978 becoming its president. After going Robert Caukwell 1960 down in 1960, he joined the Oxford Lord Chorley 1951 Andean expedition to Peru, led by Jim Curran 1985 Kim Meldrum. The team completed John Disley 1999 seven first ascents in the remote Colin Drew 1972 Allincapac (now more usually Allin David Duffield ACG 1964, AC 1968 Qhapaq) region, including the high- Chuck Evans 1988 est mountain in the area (5780m). Alan Fisher 1966 After this, Mike took a job as an Robin Garton 2008 instructor at Ullswater Outward Terence Goodfellow 1962 Bound, where he lived with his wife, Denis Greenald ACG 1953, AC 1977 Carol, and their young family for Mike Binnie Dr Tony Jones 1976 two and a half years. Helge Kolrud Asp 2011, 2015 In 1962, he returned to India to take up a post as a teacher at the Yada- Donald Lee Assoc 2007 vindra public school in Patiala, 90 miles north-west of Delhi, and remained Ralph Villiger 2015 there for two years. -

Layout 1 Copy

STACK ROCK 2020 An illustrated guide to sea stack climbing in the UK & Ireland - Old Harry - - Old Man of Stoer - - Am Buachaille - - The Maiden - - The Old Man of Hoy - - over 200 more - Edition I - version 1 - 13th March 1994. Web Edition - version 1 - December 1996. Web Edition - version 2 - January 1998. Edition 2 - version 3 - January 2002. Edition 3 - version 1 - May 2019. Edition 4 - version 1 - January 2020. Compiler Chris Mellor, 4 Barnfield Avenue, Shirley, Croydon, Surrey, CR0 8SE. Tel: 0208 662 1176 – E-mail: [email protected]. Send in amendments, corrections and queries by e-mail. ISBN - 1-899098-05-4 Acknowledgements Denis Crampton for enduring several discussions in which the concept of this book was developed. Also Duncan Hornby for information on Dorset’s Old Harry stacks and Mick Fowler for much help with some of his southern and northern stack attacks. Mike Vetterlein contributed indirectly as have Rick Cummins of Rock Addiction, Rab Anderson and Bruce Kerr. Andy Long from Lerwick, Shetland. has contributed directly with a lot of the hard information about Shetland. Thanks are also due to Margaret of the Alpine Club library for assistance in looking up old journals. In late 1996 Ben Linton, Ed Lynch-Bell and Ian Brodrick undertook the mammoth scanning and OCR exercise needed to transfer the paper text back into computer form after the original electronic version was lost in a disk crash. This was done in order to create a world-wide web version of the guide. Mike Caine of the Manx Fell and Rock Club then helped with route information from his Manx climbing web site. -

Pinnacle Club Jubilee Journal 1921-1971

© Pinnacle Club and Author All Rights Reserved PINNACLE CLUB JUBILEE JOURNAL 1921-1971 © Pinnacle Club and Author All Rights Reserved THE PINNACLE CLUB JOURNAL Fiftieth Anniversary Edition Published Edited by Gill Fuller No. 14 1969——70 © Pinnacle Club and Author All Rights Reserved THE PINNACLE CLUB OFFICERS AND COMMITTEE 1971 1921-1971 President: MRS. JANET ROGERS 8 The Penlee, Windsor Terrace, Penarth, Glamorganshire Vice-President: Miss MARGARET DARVALL The Coach House, Lyndhurst Terrace, London N.W.3 (Tel. 01-794 7133) Hon. Secretary: MRS. PAT DALEY 73 Selby Lane, Keyworth, Nottingham (Tel. 060-77 3334) Hon. Treasurer: MRS. ADA SHAW 25 Crowther Close, Beverley, Yorkshire (Tel. 0482 883826) Hon. Meets Secretary: Miss ANGELA FALLER 101 Woodland Hill, Whitkirk, Leeds 15 (Tel. 0532 648270) Hon Librarian: Miss BARBARA SPARK Highfield, College Road, Bangor, North Wales (Tel. Bangor 3330) Hon. Editor: Mrs. GILL FULLER Dog Bottom, Lee Mill Road, Hebden Bridge, Yorkshire. Hon. Business Editor: Miss ANGELA KELLY 27 The Avenue, Muswell Hill, London N.10 (Tel. 01-883 9245) Hon. Hut Secretary: MRS. EVELYN LEECH Ty Gelan, Llansadwrn, Anglesey, (Tel. Beaumaris 287) Hon. Assistant Hut Secretary: Miss PEGGY WILD Plas Gwynant Adventure School, Nant Gwynant, Caernarvonshire (Tel.Beddgelert212) Committee: Miss S. CRISPIN Miss G. MOFFAT MRS. S ANGELL MRS. J. TAYLOR MRS. N. MORIN Hon. Auditor: Miss ANNETTE WILSON © Pinnacle Club and Author All Rights Reserved CONTENTS Page Our Fiftieth Birthday ...... ...... Dorothy Pilley Richards 5 Wheel Full Circle ...... ...... Gwen M offat ...... 8 Climbing in the A.C.T. ...... Kath Hoskins ...... 14 The Early Days ..... ...... ...... Trilby Wells ...... 17 The Other Side of the Circus .... -

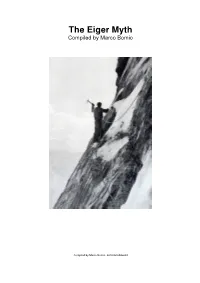

The Eiger Myth Compiled by Marco Bomio

The Eiger Myth Compiled by Marco Bomio Compiled by Marco Bomio, 3818 Grindelwald 1 The Myth «If the wall can be done, then we will do it – or stay there!” This assertion by Edi Rainer and Willy Angerer proved tragically true for them both – they stayed there. The first attempt on the Eiger North Face in 1936 went down in history as the most infamous drama surrounding the North Face and those who tried to conquer it. Together with their German companions Andreas Hinterstoisser and Toni Kurz, the two Austrians perished in this wall notorious for its rockfalls and suddenly deteriorating weather. The gruesome image of Toni Kurz dangling in the rope went around the world. Two years later, Anderl Heckmair, Ludwig Vörg, Heinrich Harrer and Fritz Kasparek managed the first ascent of the 1800-metre-high face. 70 years later, local professional mountaineer Ueli Steck set a new record by climbing it in 2 hours and 47 minutes. 1.1 How the Eiger Myth was made In the public perception, its exposed north wall made the Eiger the embodiment of a perilous, difficult and unpredictable mountain. The persistence with which this image has been burnt into the collective memory is surprising yet explainable. The myth surrounding the Eiger North Face has its initial roots in the 1930s, a decade in which nine alpinists were killed in various attempts leading up to the successful first ascent in July 1938. From 1935 onwards, the climbing elite regarded the North Face as “the last problem in the Western Alps”. This fact alone drew the best climbers – mainly Germans, Austrians and Italians at the time – like a magnet to the Eiger. -

Mountaineering War and Peace at High Altitudes

Mountaineering War and Peace at High Altitudes 2–5 Sackville Street Piccadilly London W1S 3DP +44 (0)20 7439 6151 [email protected] https://sotherans.co.uk Mountaineering 1. ABBOT, Philip Stanley. Addresses at a Memorial Meeting of the Appalachian Mountain Club, October 21, 1896, and other 2. ALPINE SLIDES. A Collection of 72 Black and White Alpine papers. Reprinted from “Appalachia”, [Boston, Mass.], n.d. [1896]. £98 Slides. 1894 - 1901. £750 8vo. Original printed wrappers; pp. [iii], 82; portrait frontispiece, A collection of 72 slides 80 x 80mm, showing Alpine scenes. A 10 other plates; spine with wear, wrappers toned, a good copy. couple with cracks otherwise generally in very good condition. First edition. This is a memorial volume for Abbot, who died on 44 of the slides have no captioning. The remaining are variously Mount Lefroy in August 1896. The booklet prints Charles E. Fay’s captioned with initials, “CY”, “EY”, “LSY” AND “RY”. account of Abbot’s final climb, a biographical note about Abbot Places mentioned include Morteratsch Glacier, Gussfeldt Saddle, by George Herbert Palmer, and then reprints three of Abbot’s Mourain Roseg, Pers Ice Falls, Pontresina. Other comments articles (‘The First Ascent of Mount Hector’, ‘An Ascent of the include “Big lunch party”, “Swiss Glacier Scene No. 10” Weisshorn’, and ‘Three Days on the Zinal Grat’). additionally captioned by hand “Caution needed”. Not in the Alpine Club Library Catalogue 1982, Neate or Perret. The remaining slides show climbing parties in the Alps, including images of lady climbers. A fascinating, thus far unattributed, collection of Alpine climbing. -

Mountaineering Books Under £10

Mountaineering Books Under £10 AUTHOR TITLE PUBLISHER EDITION CONDITION DESCRIPTION REFNo PRICE AA Publishing Focus On The Peak District AA Publishing 1997 First Edition 96pp, paperback, VG Includes walk and cycle rides. 49344 £3 Abell Ed My Father's Keep. A Journey Of Ed Abell 2013 First Edition 106pp, paperback, Fine copy The book is a story of hope for 67412 £9 Forgiveness Through The Himalaya. healing of our most complicated family relationships through understanding, compassion, and forgiveness, peace for ourselves despite our inability to save our loved ones from the ravages of addiction, and strength for the arduous yet enriching journey. Abraham Guide To Keswick & The Vale Of G.P. Abraham Ltd 20 page booklet 5890 £8 George D. Derwentwater Abraham Modern Mountaineering Methuen & Co 1948 3rd Edition 198pp, large bump to head of spine, Classic text from the rock climbing 5759 £6 George D. Revised slight slant to spine, Good in Good+ pioneer, covering the Alps, North dw. Wales and The Lake District. Abt Julius Allgau Landshaft Und Menschen Bergverlag Rudolf 1938 First Edition 143pp, inscription, text in German, VG- 10397 £4 Rother in G chipped dw. Aflalo F.G. Behind The Ranges. Parentheses Of Martin Secker 1911 First Edition 284pp, 14 illusts, original green cloth, Aflalo's wide variety of travel 10382 £8 Travel. boards are slightly soiled and marked, experiences. worn spot on spine, G+. Ahluwalia Major Higher Than Everest. Memoirs of a Vikas Publishing 1973 First Edition 188pp, Fair in Fair dw. Autobiography of one of the world's 5743 £9 H.P.S. Mountaineer House most famous mountaineers. -

Firestarters Summits of Desire Visionaries & Vandals

31465_Cover 12/2/02 9:59 am Page 2 ISSUE 25 - SPRING 2002 £2.50 Firestarters Choosing a Stove Summits of Desire International Year of Mountains FESTIVAL OF CLIMBING Visionaries & Vandals SKI-MOUNTAINEERING Grit Under Attack GUIDEBOOKS - THE FUTURE TUPLILAK • LEADERSHIP • METALLIC EQUIPMENT • NUTRITION FOREWORD... NEW SUMMITS s the new BMC Chief Officer, writing my first ever Summit Aforeword has been a strangely traumatic experience. After 5 years as BMC Access Officer - suddenly my head is on the block. Do I set out my vision for the future of the BMC or comment on the changing face of British climbing? Do I talk about the threats to the cliff and mountain envi- ronment and the challenges of new access legislation? How about the lessons learnt from foot and mouth disease or September 11th and the recent four fold hike in climbing wall insurance premiums? Big issues I’m sure you’ll agree - but for this edition I going to keep it simple and say a few words about the single most important thing which makes the BMC tick - volunteer involvement. Dave Turnbull - The new BMC Chief Officer Since its establishment in 1944 the BMC has relied heavily on volunteers and today the skills, experience and enthusi- District meetings spearheaded by John Horscroft and team asm that the many 100s of volunteers contribute to climb- are pointing the way forward on this front. These have turned ing and hill walking in the UK is immense. For years, stal- into real social occasions with lively debates on everything warts in the BMC’s guidebook team has churned out quality from bolts to birds, with attendances of up to 60 people guidebooks such as Chatsworth and On Peak Rock and the and lively slideshows to round off the evenings - long may BMC is firmly committed to getting this important Commit- they continue.