Coverage of the Tibet Crisis (March 2008) and The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Heinrich Parler

Heinrich Parler Heinrich Parler the Elder (also Heinrich of Gmünd; German: Heinrich von Gemünd der Ältere; born between 1300 and 1310 â“ circa 1370), was a German architect and master builder of the Gothic period. Heinrich Parler was probably born in Cologne between 1300 and 1310, but later lived and worked in Gmünd, an Imperial City (German: Reichsstädte) of the Holy Roman Empire.[2] He became construction manager of Holy Cross Minster in Gmünd between 1325 and 1330. Heinrich Harrer (German pronunciation: [ˈhaɪnÊɪç ˈhaÊÉ]; 6 July 1912 â“ 7 January 2006) was an Austrian mountaineer, sportsman, geographer, and author. He is best known for being on the four-man climbing team that made the first ascent of the North Face of the Eiger in Switzerland, and for his books Seven Years in Tibet (1952) and The White Spider (1959). Heinrich Harrer was born 6 July 1912 in Hüttenberg, Austria, in the district of Sankt Veit an der Glan in the state of Carinthia. His father was a Heinrich Parler the Elder (also Heinrich of Gmünd, German: Heinrich von Gemünd der Ältere; c. 1310 â“ c. 1370), was a German architect and sculptor. His masterpiece is Holy Cross Minster, an influential milestone of late Gothic architecture in the town of Schwäbisch Gmünd, Baden- Württemberg, Germany. Parler also founded the Parler family of master builders and his descendants worked in various parts of central Europe, especially Bohemia. His son, Peter Parler, became one of the major architects of the Heinrich Harrer was an Austrian mountaineer who was part of the team that made the first ascent of the formidable north wall of the Eiger in Switzerland. -

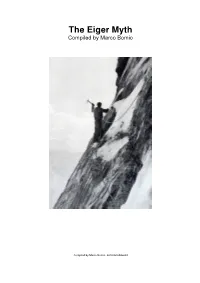

The Eiger Myth Compiled by Marco Bomio

The Eiger Myth Compiled by Marco Bomio Compiled by Marco Bomio, 3818 Grindelwald 1 The Myth «If the wall can be done, then we will do it – or stay there!” This assertion by Edi Rainer and Willy Angerer proved tragically true for them both – they stayed there. The first attempt on the Eiger North Face in 1936 went down in history as the most infamous drama surrounding the North Face and those who tried to conquer it. Together with their German companions Andreas Hinterstoisser and Toni Kurz, the two Austrians perished in this wall notorious for its rockfalls and suddenly deteriorating weather. The gruesome image of Toni Kurz dangling in the rope went around the world. Two years later, Anderl Heckmair, Ludwig Vörg, Heinrich Harrer and Fritz Kasparek managed the first ascent of the 1800-metre-high face. 70 years later, local professional mountaineer Ueli Steck set a new record by climbing it in 2 hours and 47 minutes. 1.1 How the Eiger Myth was made In the public perception, its exposed north wall made the Eiger the embodiment of a perilous, difficult and unpredictable mountain. The persistence with which this image has been burnt into the collective memory is surprising yet explainable. The myth surrounding the Eiger North Face has its initial roots in the 1930s, a decade in which nine alpinists were killed in various attempts leading up to the successful first ascent in July 1938. From 1935 onwards, the climbing elite regarded the North Face as “the last problem in the Western Alps”. This fact alone drew the best climbers – mainly Germans, Austrians and Italians at the time – like a magnet to the Eiger. -

Why the Nazis Love the Dalai Lama

Click here for Full Issue of EIR Volume 35, Number 18, May 2, 2008 ville hosted Schäfer, and wrote glowingly of Schäfer and the great “scholar” Himmler, in the journal of his own pro-Nazi Books organization, The Link, which had branches all over England and organized exchanges with the Nazi Youth in Germany. But the most interesting connection Schäfer made in Lon- don was with Sir Francis Younghusband, the British Army Why the Nazis Love Major who had led the murderous invasion of Tibet in 1904, in which 1,300 Tibetans were slaughtered along the way. The Dalai Lama Younghusband “dropped in” on Schäfer’s residence in Lon- don, advising the Nazi SS officer: “Sneak over the border, by Mike Billington that’s what I would do, then find a way around the regula- tions.” Schäfer ultimately followed this British imperial ad- vice directly, sneaking across the border from Sikkim in Janu- ary 1939. Himmler’s Crusade: The Nazi Expedition Measuring Skulls To Find the Origins of the Aryan Race The Schäfer team spent eight months in Tibet, on the eve by Christopher Hale of the Nazi Wehrmacht invasions in Europe. The 14th (and Hoboken, N.J.: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2003 current) Dalai Lama had just been chosen, but was only a 422 pages, hardcover, $30 child at the time, and had not yet been brought to Lhasa from his home in China’s Qinghai Province. The country was being When Heinrich Himmler, Reichsführer run by a regent to the Dalai Lama, who of the Nazi SS, founded the Ahnenerbe became a close friend of Schäfer. -

All the Dalai Lamas Are in Zurich

ALL THE DALAI LAMAS ARE IN ZURICH The Dalai Lama represents an institution that dates back several centuries and is unique in the world today: it is a reincarnation lineage at the intersection of spirituality and politics. Two exhibitions at the Ethnographic Museum of the University of Zurich examine the lives of the 14 Dalai Lamas who make up the lineage. Although the world learned a lot about Tibet after the rapid and painful opening of the country that followed the Chinese invasion in 1950, much of this information never received widespread attention. The 14th Dalai Lama, Nobel Peace laureate Tenzin Gyatso, symbolizes this situation in all its complexity: he is not only the leader of the Tibetan people but also one of most revered personalities in the world. At the same time he is a monk and a refugee who is blacklisted by the Chinese government whose intransigence has forced him into political activity. Surprisingly, no one has yet taken a closer look at the unique, centuries-old institution of the Dalai Lamas and their 14 reincarnations. The two exhibitions in Zurich with their exclusive focus on the Dalai Lamas break new ground and represent a significant international cultural event. The 14 Dalai Lamas Tibetan reincarnations of Bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara The main exhibition on the 1st floor of the Ethnographic Museum presents the 600-year history of Tibet as personified by a single line of some of its leading historical figures. Displayed in a succession of rooms and smaller spaces are historic treasures that relate to each of the 14 men who have wielded spiritual and secular power. -

Seven Years in Tibet' Directed by Jean-Jacques Annaud

HIMALAYA, the Journal of the Association for Nepal and Himalayan Studies Volume 18 Number 1 Himalayan Research Bulletin: Article 14 Solukhumbu and the Sherpa, Part Two: Ladakh 1998 Book review of 'Seven Years in Tibet' directed by Jean-Jacques Annaud Philippe Foret University of Oklahoma Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/himalaya Recommended Citation Foret, Philippe. 1998. Book review of 'Seven Years in Tibet' directed by Jean-Jacques Annaud. HIMALAYA 18(1). Available at: https://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/himalaya/vol18/iss1/14 This Book Review is brought to you for free and open access by the DigitalCommons@Macalester College at DigitalCommons@Macalester College. It has been accepted for inclusion in HIMALAYA, the Journal of the Association for Nepal and Himalayan Studies by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Macalester College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Why Sunlit Vistas Could Not Be Grander: A Review of Seven Years in Tibet Jean-Jacques Annaud, director. Seven Years in Tibet (a film from Heinrich Harrer's book) , Columbia Pictures 1997. The movie Seven Years in Tibet is based on a travelogue, published in Vienna in 1952, that later became what the French call "un bestseller." "Sieben Jahre in Tibet. Mein Leben am Hofe des Dalai Lama" was translated into fourteen languages and had sold more than four million copies before the release of the movie last fall. As origin ally published the book included sixty-six pictures taken by Heinrich Harrer while he was living at the court of the Dalai Lama. These photographs documented the mundane and religious life of Lhasa and forty years later were exhibited by two museums , the Liechtensteinischen Landesmuseum of Vaduz and the Volkerkundemuseum of the University of Zurich and were republished in their own catalogue. -

German Expedition to Tibet (1938-1939)

ASIA PROGRAMME GERMAN EXPEDITION TO TIBET (1938-1939) BY CHARLIE CARON PhD Student, EPHE-ICP JANUARY 2021 ASIA FOCUS #153 ASIA FOCUS #153 – ASIA PROGRAMME / January 2021 n 1938, five German scientists embarked on an extraordinary quest. They risked I their lives crossing the highest mountains in the world to reach one of the most remote kingdoms: Tibet. The scientific expedition was officially tasked with researching the zoology and anthropology of the country. But eventually, the data collected for the SS1 would serve a much darker purpose. Their secret mission was to discover the origins of the Aryan race, and the vestiges of this civilization, which would have disappeared on the roof of the world. This endeavour would allow the Nazis to rewrite history and forge a new past, allowing them to legitimize the new world they claimed to set up at the time: that of a pure Reich, to last 1,000 years. The expedition, led by Heinrich Himmler, was under the direction of the Ahnenerbe Forschungs und Lehrgemeinschaft, the Society for Research and Education on Ancestral Inheritance. This multidisciplinary research institute sought to study the sphere, the spirit, the achievements and the heritage of the Nordic Indo-European race, with archaeological research, racial anthropology and cultural history of the Aryan race. Its aim was to prove the validity of Nazi theories on the racial superiority of the Aryans over supposedly inferior races, as well as to Germanize the sufficiently pure inhabitants of the Nazi Lebensraum. ERNST SCHÄFER GERMAN EXPEDITION -

Prism of Tibetan Images and Realities| One Generation of Tibet Lovers in Kalimpong, India

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 1994 Prism of Tibetan images and realities| One generation of Tibet Lovers in Kalimpong, India Jacqueline A. Hiltz The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Hiltz, Jacqueline A., "Prism of Tibetan images and realities| One generation of Tibet Lovers in Kalimpong, India" (1994). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 3307. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/3307 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Maureen and Mike MANSFIELD LIBIiARY The University of Montana Permission is granted by tlie autlior to reproduce tlais material in its entirety, provided that tliis material is used for scholarly purposes and is properly cited in published works and repoits. ** Please check "Yes" or "No " and.provide signature*"^ Yes, I grant permission ^ No, I do not grant pemiission Author's Signature Date: ' Any coDYiiic for commercial numoses or financial paiii may be undeitaken A PRISM OF TIBETAN IMAGES AND REALITIES: ONE GENERATION OF TIBET LOVERS IN KALIMPONG, INDIA by Jacqueline A. Hiltz B.A. Stanford University, 1984 presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History The University of Montana 1994 Approved by: Chairpereon ;an. -

General Summer Reading List

Summer Reading List – General Recent Broward County visiting Authors Kim Barnes, who work, In the Wilderness: Coming of Age in an Unknown Country was a Pulitzer Prize finalist; Investigative journalist, Ace Atkins, formerly of The Tampa Tribune, and Pulitzer Prize nominee for his investigation of a 1950s murder which inspired the 2006 novel, White Shadow Jeanne Laskas, syndicate columnist for The Washington Post, Esquire, GQ, and others whose stories have appeared in anthologies including The Best American Sports Writing Entrepreneur Lowell Hawthorne who grew up in rural Jamaica and went on to establish the largest Caribbean business in America chronicled in The Baker's Son Award-winning author and graphic artist team depicting the tumultuous times of Frederick Douglass, Abraham Lincoln, and the end of slavery in America in the graphic novel, The Hammer and the Anvil; any many others. Just Read, Florida! 2013 Summer Recommended Reading List Here is the link for Just Read, Florida! Note: Please enter the site to access the links. - http://www.justreadfamilies.org/SummerReadingList.pdf Just Read, Families! New! Just Read, Florida! Summer Reading Information • New! Summer Literacy Adventure with First Lady Ann Scott - Memo ◦ Summer Literacy Adventure with First Lady Ann Scott - Attachment • Make your Summer Reading Pledge here! • Elementary Summer Reading Loss Brochure • Secondary Summer Reading Loss Brochure • 2013 Summer Recommended Reading List Barnes & Noble New Books for Teens • The Rithmatist by Brandon Sanderson Overview From #1 New York Times bestselling author Brandon Sanderson: his debut novel for the young adult audience More than anything, Joel wants to be a Rithmatist. Chosen by the Master in a mysterious inception ceremony, Rithmatists have the power to infuse life into two-dimensional figures known as Chalklings. -

Nanga Parbat Pilgrimage: the Lonely Challenge

Nanga Parbat Pilgrimage: The Lonely Challenge Nanga Parbat Pilgrimage: The Lonely Challenge; 353 pages; Hermann Buhl; The Mountaineers Books, 1998; 0898866103, 9780898866100; 1998; Autobiography of Hermann Buhl, whose solo, unaided climb of Nanga Parbat is thought to be a greater achievement than Hillary and Tenzing's climb on Everest. file download xizabir.pdf In 1938 Anderl Heckmair made the first ascent of the North Face of the Eiger, a monumental climb that cemented his place in history. In My Life he tells the story of how he; Jan 12, 2015; My Life; 300 pages; Sports & Recreation; ISBN:9781910240304; Anderl Heckmair, Reinhold Messner, Tim Carruthers; Eiger North Face, Grandes Jorasses and other Adventures pdf file 160 pages; Mar 1, 2012; Jon E. Lewis; The Mammoth Book of On The Edge; Sports & Recreation; ISBN:9781780337333; No one sees clearer than an individual whose life is hanging by the finger tips on the edge of an abyss. Probing the furthest reaches of human daring and endurance, here are 28 The 336 pages; Biography & Autobiography; Heinrich Harrer; ISBN:9780007347575; The White Spider; A classic of mountaineering literature, this is the story of the harrowing first ascent of the North Face of the Eiger, the most legendary and terrifying climb in history; Jun 24, 2010 download Nanga Parbat Pilgrimage: The Lonely Challenge pdf Climbs and Ski Runs; ISBN:9781906148874; Frank Smythe; 300 pages; Feb 7, 2014; "Why do you climb?" The mountaineer has no answer to this question. The best things in the world cannot adequately be expressed in speech or print; they are part of the soul; Sports & Recreation 320 pages; ISBN:9781926855394; In the Heart of the Canadian Rockies; History; There is a wonderful fascination about mountains. -

Summer News 2021

SUMMER NEWS 2021 Contact: Martina Jamnig E-mail: [email protected] Tel: 076 25 26 7630 Press.austria.info/uk Dear reader, It is with full of hope that we are gearing up for the coming summer season, and the same can be said for our partners in Austria. Never before have we had so much news to tell you about, which not only delights us, but also makes us want to go on holiday in Austria. Numerous new hotels, chalets and apartments have been built across the country. Guests can sleep under the stars of the Biosphere Reserve Großes Walsertal in the mobile Dream.Alive-Lodge, a glass-enclosed hotel room. Existing establishments are investing in conversions and extensions with great attention to detail, such as Hotel Salzburger Hof in Leogang. The building has been extended and now includes a 1,200 m² panoramic wellness area with a 20.5 m long outdoor infinity pool. The new (long-distance) hiking trails are sure to be popular amongst those who can’t wait to get active outdoors this summer. Ambitious hikers can opt for the Hohe Tauern Panorama Trail, for example, which will be offering stunning views of Austria’s highest mountains from mid-May. Quite fittingly, Hohe Tauern National Park is celebrating its 50th anniversary this year. And there are new options for cyclists too. Some of the SalzburgerLand regions have picked up on the gravel biking trend and are offering tours. In the Kitzbüheler Alpen, the KAT Bike trail is being updated. There are also nature and animal experiences to look forward to. -

The Seven Summits on the Highest Mountains Ofall Continents

The Seven Summits On the highest mountains ofall continents OSWALD OELZ (Plates 79,80) T he Swiss climber Dolf Reist was the first to succeed in climbing the highest peaks of five continents. He reached the summit of Mont Blanc in his early years, climbed Mount Everest in 1956, MountMcKinley in 1961, Kilimanjaro in 1969 and Aconcagua in 1971. At that time the highest point of Antarctica, the Vinson Massif, was inaccessible; and Mount Kosciusko in Australia was considered too insignificant to justify such a long trip from Europe. The Japanese climber Naomi Uemura later repeated Dolf Reist's feat. In 1981 Dick Bass, a millionaire from Texas, created the idea ofclimbing the 'Seven Summits' which include the Vinson Massif and Mount Kosciusko. Furthermore, MountElbrus in the Caucasus replaced Mont Blanc as the highest peak in Europe. Although it took Dick Bass more than four years, instead ofone year as planned, to climb his Seven Summits, his achievement which culminated on the summit of Mount Everest in October 1985 was most remarkable, particularly if one considers the fact that Bass was not a mountaineer when he started thinking about the Seven Summits. The Canadian mountaineer Pat Morrow competed with Dick Bass for the first full set of Seven Summits. He lost the race because he was unable to raise enough money to hire a plane for Antarctica. However, he introduced another hurdle by claiming that Carstensz Pyramid in Irian Jaya is the highest peak of Australasia. He argued, as did others such as Reinhold Messner, that Mount Kosciusko, whose top can be reached by car, should not be regarded as the highest point of that area but rather Carstensz Pyramid, a much higher and more difficult limestone mountain which is almost inaccessible for political reasons. -

Read Book Seven Years in Tibet Ebook

SEVEN YEARS IN TIBET PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Heinrich Harrer,Richard Graves | 336 pages | 17 Nov 1988 | HarperCollins Publishers | 9780586087077 | English | London, United Kingdom Seven Years in Tibet () - Plot Summary - IMDb Finally near the end of the book it was mentioned that they were reused and handed out to others. And this leads to my next complaint. Listeners are left with questions. Terms are not clearly defined so you search for understanding, to make sense of what you are told. At one point, my husband and I, we were both listening to the audio book together, did not agree on who had been killed! Finally I understood. So the book isn't perfect, but don't let that determine whether to pick it up or not. The reader follows an exciting adventure and there is a lot to learn here about old Tibet, before the Chinese invasion in One other point which I found intriguing is how there are so many rules to be followed In the Buddhist philosophy no creature can be killed, so of course meat cannot be eaten. But, but, but, but people do need some meat so it is quite handy if the people in neighboring Nepal can provide this This bothered me tremendously. Time and time again, the Nepalese were handy to have to do that which the Buddhist faith did not allow to be done in Tibet. And it bothered me that in sport events where it was determined that the Dali Lama must win, he of course always did win. Is that real competition? Never mind, just my own thoughts troubling me.