In Memoriam 1936 - 2016 Mike Was Born in Mumbai

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Module No. 1840 1840-1

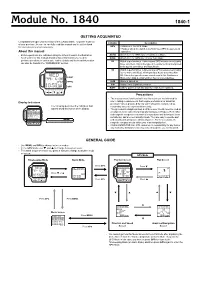

Module No. 1840 1840-1 GETTING ACQUAINTED Congratulations upon your selection of this CASIO watch. To get the most out Indicator Description of your purchase, be sure to carefully read this manual and keep it on hand for later reference when necessary. GPS • Watch is in the GPS Mode. • Flashes when the watch is performing a GPS measurement About this manual operation. • Button operations are indicated using the letters shown in the illustration. AUTO Watch is in the GPS Auto or Continuous Mode. • Each section of this manual provides basic information you need to SAVE Watch is in the GPS One-shot or Auto Mode. perform operations in each mode. Further details and technical information 2D Watch is performing a 2-dimensional GPS measurement (using can also be found in the “REFERENCE” section. three satellites). This is the type of measurement normally used in the Quick, One-Shot, and Auto Mode. 3D Watch is performing a 3-dimensional GPS measurement (using four or more satellites), which provides better accuracy than 2D. This is the type of measurement used in the Continuous LIGHT Mode when data is obtained from four or more satellites. MENU ALM Alarm is turned on. SIG Hourly Time Signal is turned on. GPS BATT Battery power is low and battery needs to be replaced. Precautions • The measurement functions built into this watch are not intended for Display Indicators use in taking measurements that require professional or industrial precision. Values produced by this watch should be considered as The following describes the indicators that reasonably accurate representations only. -

Leonetti-Geo3.Pdf

GEO 3 Il Mondo: i paesaggi, la popolazione e l'economia 3 media:-testo di Geografia C3 pag. 2 Geo 3: Il Mondo I paesaggi, la popolazione, l’economia Per la Scuola Secondaria di Primo Grado a cura di Elisabetta Leonetti Coordinamento editoriale: Antonio Bernardo Ricerca iconografica: Cristina Capone Cartine tematiche: Studio Aguilar Copertina Ginger Lab - www.gingerlab.it Settembre 2013 ISBN 9788896354513 Progetto Educationalab Mobility IT srl Questo libro è rilasciato con licenza Creative Commons BY-SA Attribuzione – Non commerciale - Condividi allo stesso modo 3.0 http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/legalcode Alcuni testi di questo libro sono in parte tratti da Wikipedia Versione del 11/11/2013 Modificato da [email protected] – 23/9/15 INDICE GEO 3 Glossario Mappe-Carte AulaVirtuale 3 media:-testo di Geografia C3 pag. 3 Presentazione Questo ebook fa parte di una collana di ebook con licenza Creative Commons BY-SA per la scuola. Il titolo Geo C3 vuole indicare che il progetto è stato realizzato in modalità Collaborativa e con licenza Creative Commons, da cui le tre “C” del titolo. Non vuole essere un trattato completo sull’argomento ma una sintesi sulla quale l’insegnante può basare la lezione, indicando poi testi e altre fonti per gli approfondimenti. Lo studente può consultarlo come riferimento essenziale da cui partire per approfondire. In sostanza, l’idea è stata quella di indicare il nocciolo essenziale della disciplina, nocciolo largamente condiviso dagli insegnanti. La licenza Creative Commons, con la quale viene rilasciato, permette non solo di fruire liberamente l’ebook ma anche di modificarlo e personalizzarlo secondo le esigenze dell’insegnante e della classe. -

Moüjmtaiim Operations

L f\f¿ áfó b^i,. ‘<& t¿ ytn) ¿L0d àw 1 /1 ^ / / /This publication contains copyright material. *FM 90-6 FieW Manual HEADQUARTERS No We DEPARTMENT OF THE ARMY Washington, DC, 30 June 1980 MOÜJMTAIIM OPERATIONS PREFACE he purpose of this rUanual is to describe how US Army forces fight in mountain regions. Conditions will be encountered in mountains that have a significant effect on. military operations. Mountain operations require, among other things^ special equipment, special training and acclimatization, and a high decree of self-discipline if operations are to succeed. Mountains of military significance are generally characterized by rugged compartmented terrain witn\steep slopes and few natural or manmade lines of communication. Weather in these mountains is seasonal and reaches across the entireSspectrum from extreme cold, with ice and snow in most regions during me winter, to extreme heat in some regions during the summer. AlthoughNthese extremes of weather are important planning considerations, the variability of weather over a short period of time—and from locality to locahty within the confines of a small area—also significantly influences tactical operations. Historically, the focal point of mountain operations has been the battle to control the heights. Changes in weaponry and equipment have not altered this fact. In all but the most extreme conditions of terrain and weather, infantry, with its light equipment and mobility, remains the basic maneuver force in the mountains. With proper equipment and training, it is ideally suited for fighting the close-in battfe commonly associated with mountain warfare. Mechanized infantry can\also enter the mountain battle, but it must be prepared to dismount and conduct operations on foot. -

Module No. 2240 2240-1

Module No. 2240 2240-1 GETTING ACQUAINTED Precautions • Congratulations upon your selection of this CASIO watch. To get the most out The measurement functions built into this watch are not intended for of your purchase, be sure to carefully read this manual and keep it on hand use in taking measurements that require professional or industrial for later reference when necessary. precision. Values produced by this watch should be considered as reasonably accurate representations only. About This Manual • Though a useful navigational tool, a GPS receiver should never be used • Each section of this manual provides basic information you need to perform as a replacement for conventional map and compass techniques. Remember that magnetic compasses can work at temperatures well operations in each mode. Further details and technical information can also be found in the “REFERENCE”. below zero, have no batteries, and are mechanically simple. They are • The term “watch” in this manual refers to the CASIO SATELLITE NAVI easy to operate and understand, and will operate almost anywhere. For Watch (Module No. 2240). these reasons, the magnetic compass should still be your main • The term “Watch Application” in this manual refers to the CASIO navigation tool. • SATELLITE NAVI LINK Software Application. CASIO COMPUTER CO., LTD. assumes no responsibility for any loss, or any claims by third parties that may arise through the use of this watch. Upper display area MODE LIGHT Lower display area MENU On-screen indicators L K • Whenever leaving the AC Adaptor and Interface/Charger Unit SAFETY PRECAUTIONS unattended for long periods, be sure to unplug the AC Adaptor from the wall outlet. -

Mountaineering War and Peace at High Altitudes

Mountaineering War and Peace at High Altitudes 2–5 Sackville Street Piccadilly London W1S 3DP +44 (0)20 7439 6151 [email protected] https://sotherans.co.uk Mountaineering 1. ABBOT, Philip Stanley. Addresses at a Memorial Meeting of the Appalachian Mountain Club, October 21, 1896, and other 2. ALPINE SLIDES. A Collection of 72 Black and White Alpine papers. Reprinted from “Appalachia”, [Boston, Mass.], n.d. [1896]. £98 Slides. 1894 - 1901. £750 8vo. Original printed wrappers; pp. [iii], 82; portrait frontispiece, A collection of 72 slides 80 x 80mm, showing Alpine scenes. A 10 other plates; spine with wear, wrappers toned, a good copy. couple with cracks otherwise generally in very good condition. First edition. This is a memorial volume for Abbot, who died on 44 of the slides have no captioning. The remaining are variously Mount Lefroy in August 1896. The booklet prints Charles E. Fay’s captioned with initials, “CY”, “EY”, “LSY” AND “RY”. account of Abbot’s final climb, a biographical note about Abbot Places mentioned include Morteratsch Glacier, Gussfeldt Saddle, by George Herbert Palmer, and then reprints three of Abbot’s Mourain Roseg, Pers Ice Falls, Pontresina. Other comments articles (‘The First Ascent of Mount Hector’, ‘An Ascent of the include “Big lunch party”, “Swiss Glacier Scene No. 10” Weisshorn’, and ‘Three Days on the Zinal Grat’). additionally captioned by hand “Caution needed”. Not in the Alpine Club Library Catalogue 1982, Neate or Perret. The remaining slides show climbing parties in the Alps, including images of lady climbers. A fascinating, thus far unattributed, collection of Alpine climbing. -

Report of the Fifth Meeting of the Surveillance

INTERNATIONAL CIVIL AVIATION ORGANIZATION ASIA AND PACIFIC OFFICE REPORT OF THE FIFTH MEETING OF THE SURVEILLANCE IMPLEMENTATION COORDINATION GROUP (SURICG/5) Web-conference, 22 - 24 September 2020 The views expressed in this Report should be taken as those of the Meetings and not the Organization. Approved by the Meeting and published by the ICAO Asia and Pacific Office, Bangkok SURICG/5 Table of Contents i-2 HISTORY OF THE MEETING Page 1. Introduction ...................................................................................................................................... i-3 2. Opening of the Meeting ................................................................................................................... i-3 3. Attendance ....................................................................................................................................... i-3 4. Officers and Secretariat .................................................................................................................... i-3 5. Organization, working arrangements and language ......................................................................... i-3 6. Draft Conclusions, Draft Decisions and Decision of SURICG - Definition .................................... i-3 REPORT ON AGENDA ITEMS Agenda Item 1: Adoption of Agenda ............................................................................................... 1 Agenda Item 2: Review of outcomes of relevant meetings including ICAO 40th Assembly, DGCA/56 and APANPIRG/30 on Surveillance -

CC J Inners 168Pp.Indd

theclimbers’club Journal 2011 theclimbers’club Journal 2011 Contents ALPS AND THE HIMALAYA THE HOME FRONT Shelter from the Storm. By Dick Turnbull P.10 A Midwinter Night’s Dream. By Geoff Bennett P.90 Pensioner’s Alpine Holiday. By Colin Beechey P.16 Further Certifi cation. By Nick Hinchliffe P.96 Himalayan Extreme for Beginners. By Dave Turnbull P.23 Welsh Fix. By Sarah Clough P.100 No Blends! By Dick Isherwood P.28 One Flew Over the Bilberry Ledge. By Martin Whitaker P.105 Whatever Happened to? By Nick Bullock P.108 A Winter Day at Harrison’s. By Steve Dean P.112 PEOPLE Climbing with Brasher. By George Band P.36 FAR HORIZONS The Dragon of Carnmore. By Dave Atkinson P.42 Climbing With Strangers. By Brian Wilkinson P.48 Trekking in the Simien Mountains. By Rya Tibawi P.120 Climbing Infl uences and Characters. By James McHaffi e P.53 Spitkoppe - an Old Climber’s Dream. By Ian Howell P.128 Joe Brown at Eighty. By John Cleare P.60 Madagascar - an African Yosemite. By Pete O’Donovan P.134 Rock Climbing around St Catherine’s Monastery in the Sinai Desert. By Malcolm Phelps P.142 FIRST ASCENTS Summer Shale in Cornwall. By Mick Fowler P.68 OBITUARIES A Desert Nirvana. By Paul Ross P.74 The First Ascent of Vector. By Claude Davies P.78 George Band OBE. 1929 - 2011 P.150 Three Rescues and a Late Dinner. By Tony Moulam P.82 Alan Blackshaw OBE. 1933 - 2011 P.154 Ben Wintringham. 1947 - 2011 P.158 Chris Astill. -

Pinnacle Club Journal

© Pinnacle Club and Author All Rights Reserved THE PINNACLE CLUB JOURNAL No. 20 1985 - 87 © Pinnacle Club and Author All Rights Reserved THE PINNACLE CLUB JOURNAL 1985 - 87 Edited by Stephanie Rowland © Pinnacle Club and Author All Rights Reserved THE PINNACLE CLUB Founded 1921 OFFICERS AND COMMITTEE 1987 President ANNABELLE BARKER Hafod Aur, Pont y Pant, Dolwyddelen, Gwynedd. (06906 272) Vice President Sheila Cormack Hon. Secretary Jean Drummond 10 Crichton Cottages, Crichton, Pathhead, Midlothian. (0875 32 0445) Hon. Treasurer Stella Adams Hon. Meets Secretary Denise Wilson Hon. Hut Secretary Rhona Lampard Hon. Editor Stephanie Rowland Springfield, Culbokie, Dingwall, Ross-shire. (034987 603) Committee Tansy Hardy Sheila Lockhart Geraldine Westrupp Sue Williscroft Sally Kier Betty Whithead (Dinner Organiser) Hon. Auditor Hon. Librarian Ann Wheatcroft Avis Reynolds © Pinnacle Club and Author All Rights Reserved Contents Page How I Became Brave Annabelle Barker ..................... 5 True Grit Dave Woolley and Andy Llewelyn ..................... 12 An Apology By a Mere Man Anon ..................................... 16 'Burro Perdido' and other Escapades Angela Soper .......................... 18 A Reconaissance of Ananea Belinda Swift ........................... 22 Sardines and Apricots: a month in Hunza Margaret Clennett .................... 25 The Coast to Coast Walk Dorothy Wright ....................... 29 British Gasherbrum IV Chris Watkins and Expedition 1986 Rhona Lampard .................... 31 Two Walks in Kashmir Sheila McKemmie -

A Brief History of the Climbers' Club

A BRIEF HISTORY OF THE CLIMBERS' CLUB A PERSONAL VIEW BYPIP HOPKINSON In August and September during the 1890s a group of about 40 men met regularly at the Pen y Gwryd to climb and explore the Welsh hills and crags. After one Saturday evening's dinner it was proposed that a club be formed. This idea was pursued at a dinner in London on 19th May 1897 at the Café Monico and the next dinner was fixed for 6th December 1897 at Pen y Gwryd. This was not well-attended; only 25 of the group turned up. Nevertheless the foundations of the Club were laid at this dinner. The resolution 'That a Climbing Club be formed' was proposed by Mr Roderick Williams and seconded by Mr H. G. Gotch, both of whom were already Alpine Club members. This was approved by the group and a provisional Club committee was elected. The provisional committee drafted and sent out a circular to all those known as climbers whose names could be obtained from various sources. It read: The Climbers' Club Dear Sir, It has been determined to establish a Club under the above title. The object of the Club will be to encourage mountaineering, particularly in England, Ireland and Wales, and to serve as a bond of union amongst all lovers of mountain activity. The qualifications of members will be determined by the Committee, who have the sole power of election. The officers will be a President, two Vice-Presidents, an Honorary Secretary and an Honorary Treasurer. The Committee will consist of the officers and nine additional members all to be elected annually at the Annual Meeting. -

Cairngorm Club Library List Oct2020 Edited Kjt30oct2020

Cairngorm Club Library Holding Re-Catalogued at Kings College Special Collections October 2020 To find current Library reference data, availability, etc., search title, author, etc. in the University Catalogue: see www.abdn.ac.uk/library Type / Creator / Imprint title Johnson, Samuel, (London : Strahan & Cadell, 1775.) A journey to the Western Islands of Scotland. Taylor, George, (London : the authors, 1776) Taylor and Skinner's survey and maps of the roads of North Britain or Scotland. Boswell, James, (London : Dilly, 1785.) The journal of a tour to the Hebrides, with Samuel Johnson, LL. D. / . Grant, Anne MacVicar, (Edinburgh : Grant, 1803) Poems on various subjects. Bristed, John. (London : Wallis, 1803.) A predestrian tour through part of the Highlands of Scotland, in 1801. Campbell, Alexander, (London : Vernor & Hood, 1804) The Grampians desolate : a poem. Grant, Anne MacVicar, (London : Longman, 1806.) Letters from the mountains; being the real correspondence of a lady between the years 1773 and Keith, George Skene, (Aberdeen : Brown, 1811.) A general view of the agriculture of Aberdeenshire. Robson, George Fennell. (London : The author, 1814) Scenery of the Grampian Mountains; illustrated by forty etchings in the soft ground. Hogg, James, (Edinburgh : Blackwood & Murray, 1819.) The Queen's wake : a legendary poem. Sketches of the character, manners, and present state of the Highlanders of Scotland : with details Stewart, David, (Edinburgh : Constable, 1822.) of the military service of the Highland regiments. The Highlands and Western Isles of Scotland, containing descriptions of their scenery and antiquities, with an account of the political history and ancient manners, and of the origin, Macculloch, John, (London : Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme, language, agriculture, economy, music, present condition of the people, &c. -

Joe Tasker Obituary

Joe Tasker 1948-82 by Dick Renshaw Joe was born in Hull in 1948 and five years later moved to Teeside where his father worked as a school caretaker until his retirement. Joe was one of ten children in a very close-knit family from which a strong sense of consideration and thoughtfulness for others seemed to develop. Several members of his family were usually at the airport when Joe left on expedition or returned. Just before leaving on his last expedition to Everest Pete wondered whether Joe, noted for turning up at the last minute, would be on time to meet the press. ‘He will be,’ said someone else. ‘Joe might keep the press of the world waiting but never his family.’ As the eldest of a strong Catholic family, Joe was sent to Ushaw College, a Jesuit seminary, at the age of thirteen. His seven years there were to have a lasting effect on him in many ways. It was there that he started climbing when he was fifteen, in a quarry behind the college, with the encouragement of Father Barker, one of the priests, and in a well-stocked library his imagination was fired by epic adventures in the mountains. He was always grateful for the excellent education he had received and his amazing will power and stoicism may perhaps have been partly due to the somewhat spartan way of life and to the Jesuit ideals of spiritual development through self-denial. He started his training as a priest but at twenty he realised that he did not have the vocation and decided to leave – the hardest decision of his life. -

The Modernisation of Elite British Mountaineering

The Modernisation of Elite British Mountaineering: Entrepreneurship, Commercialisation and the Career Climber, 1953-2000 Thomas P. Barcham Thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of De Montfort University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Submission date: March 2018 Contents Abstract ................................................................................................................................................... 4 Acknowledgments ................................................................................................................................... 5 Table of Abbreviations and Acronyms .................................................................................................... 6 Table of Figures ....................................................................................................................................... 7 Chapter 1. Introduction .......................................................................................................................... 8 Literature Review ............................................................................................................................ 14 Definitions, Methodology and Structure ........................................................................................ 29 Chapter 2. 1953 to 1969 - Breaking a New Trail: The Early Search for Earnings in a Fast Changing Pursuit ..................................................................................................................................................