Character in the Age of Adam Smith by Shannon Frances Chamberlain

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

From Pig Farmer to Infidel: Hidden Identities, Diasporic Infertility, and Transethnic Kinship in Contemporary British Jewish Cinema

This is a repository copy of From Pig Farmer to Infidel: Hidden Identities, Diasporic Infertility, and Transethnic Kinship in Contemporary British Jewish Cinema. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/85099/ Version: Accepted Version Book Section: Sternberg, C (2016) From Pig Farmer to Infidel: Hidden Identities, Diasporic Infertility, and Transethnic Kinship in Contemporary British Jewish Cinema. In: Abrams, N and Lassner, P, (eds.) Hidden in Plain Sight: Jews and Jewishness in British Film, Television, and Popular Culture. Cultural Expressions of World War II: Interwar Preludes, Responses, Memory . Northwestern University Press , Evanston, Illinois , pp. 181-204. ISBN 978-0-8101-3282-5 Copyright © 2016 by Northwestern University Press. Published 2016. All rights reserved. This is an author produced version of a book chapter published in Hidden in Plain Sight: Jews and Jewishness in British Film, Television, and Popular Culture. Uploaded with permission from the publisher. Reuse Items deposited in White Rose Research Online are protected by copyright, with all rights reserved unless indicated otherwise. They may be downloaded and/or printed for private study, or other acts as permitted by national copyright laws. The publisher or other rights holders may allow further reproduction and re-use of the full text version. This is indicated by the licence information on the White Rose Research Online record for the item. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. -

9Th Grade 2016 Summer Reading All Forms

Hampton Christian Academy Upper School May 2016 Dear Parents, As we enter this summer, all of us—parents, students, and teachers—are excited about the well-earned break from the rigors of school. At the same time, however, we recognize that much hard-earned knowledge tends to slip away during the summer months unless we take measures to retain mental acuity. There is no question that one of the most valuable components to your student's academic success is a sustained pattern of reading. Students who are strong, avid readers are generally proficient students and competent test-takers. Hampton Christian Academy remains committed to doing all we can to develop our students’ reading skills and help them discover the life-long pleasure reading can bring to their lives. Each student in grades 7 - 11 is required to read a total of three books during the summer break. (Honors English students will have additional summer reading and writing assignments – see school website.) One of the three books has already been chosen for the student based on thematic content and grade level. This selected book will then be discussed the first week of school and a test will be given in class on the required book. This test will account for 50% of the student's summer reading test grade. An additional 25% will be earned by successfully completing a computerized Accelerated Reader quiz on a book from the grade level Accelerated Reader book list. AR quizzes consist of 10-20 questions focusing on reading comprehension. Students may drop by the school library on any Friday during the summer from 9 A.M. -

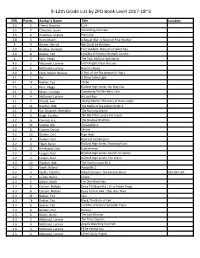

9-12Th Grade List by ZPD Book Level 2017-18~3

9-12th Grade List by ZPD Book Level 2017-18~3 ZPD Points Author's Name Title Location 3.2 5 Friend, Natasha Lush 3.5 7 Colasanti, Susan Something Like Fate 3.5 6 Hamilton, Virginia Plain City 3.8 3 Harry Mazer A Boy at War: A Novel of Pearl Harbor 4 4 Barnes, Derrick We Could be Brothers 4.0 5 Bradley, Kimberly For Freedom: Story of a French Spy 4.0 8 Dekker, Ted Lost Bks of History Series#5: Lunatic 4 3 Kern, Peggy The Test, Bluford High Series 4.0 5 McDaniel, Lurlene Until Angels Close my Eyes 4.0 5 McDaniel, Lurlene Heart to Heart 4.0 4 Peck, Robert Newton A Part of the Sky (sequel to Pigs ) 4.1 5 Avi A Place Called Ugly 4.1 14 Dekker, Ted Thr3e 4.1 3 Kern, Peggy Bluford High Series: No Way Out 4.1 4 Mazer, Lerangis Somebody Tell Me Who I Am 4.1 4 McDaniel, Lurlene Hit and Run 4.1 7 Rinaldi, Ann Taking Liberty: The Story of Oney Judge 4.1 12 Riordan, Rick The Battle of the Labyrinth Bk 4 4.1 9 Van Draanen, Wendelin The Running Dream 4.1 9 Voigt, Cynthia Tell Me if the Lovers are Losers 4.2 6 Cannon, A.E. The Shadow Brothers 4.2 13 Condie, Ally Crossed Bk 2 4.2 8 Cooner, Donna Skinny 4.2 10 Deuker, Carl High Heat 4.2 8 Deuker, Carl Heart of a Champion 4.2 4 Folan, Karyn Bluford High Series: Breaking Point 4.2 12 Honeyman, Kay Interference 4.2 3 Langan, Paul Bluford High Series: Search for Safety 4.2 3 Langan, Paul Bluford High Series: The Fallen 4.2 10 Riordan, Rick The Titan’s Curse Bk 3 4.2 10 Smith, Roland Above Bk 2 4.2 5 Yeatts, Tabatha Albert Einstein: The Miracle Mind 530.092 YEA 4.2 6 Lo'pez, Diana Choke 4.3 5 Albom, Mitch For -

The Infidel.Mmsw

"THE INFIDEL" by Robert Carl Johnson Robert Carl Johnson 7510 E. Gem Shores Rd. Hayden Lake, ID 83835 (208) 772-9838 Cell (208) 818-6727 [email protected] FADE IN: INT. HEART MONITOR - DAY SUPER: "JANUARY 2ND. PRESENT DAY." A heartbeat's electrical line moves up and down across the screen - line movement goes erratic - goes flatline - steady SHRILL alarm sends an alert. FEMALE (V.O.) Code blue. Room 626. Code blue. Room 626. EXT. PARK - NIGHT (FLASHBACK) SUPER: "SEPTEMBER 11TH - 113 DAYS PRIOR." A speck of light flickers, grows brighter, reflects a child's tear-streaked cheeks. She and a group (all ages) share grief and pride and hold candles and small American Flags at a memorial. Multitudes of flowers and stuffed animals lay at a sign - "GOD BLESS AMERICA, OUR TROOPS AND TERRORISTS' VICTIMS." EXT. ANCIENT MIDDLE EAST CITY - DAY The sunrise reflects timeless beauty off spiral and domed ROOFS. A PRAYER CHANT's EERINESS seeps into AN ALLEY, shadowed and cobbled. Rats, ragged children, mangey cats and dogs scavenge trash-food. The CHANT NARROW STREET joins angry MURMURS as people scurry into a HUGE SQUARE, swallowed into a gathering horde as ANGRY SHOUTS and AUTOMATIC gun SHOTS rise to a frenzy and inflict the CHANT's merciless death. A woman of stature is unaffected by chaos. Her berka's fabric is of finest quality (no veil). Diamond dust glitters on manicured fingernails. 2. Her olive complexion is as smooth as melted Hagen Daz ice cream; radiant dark eyes as elusive as a frightened chameleon. But most striking are her lips; a slow twist stitches tight wetness of halves that men have died for since Adam and Eve. -

Young Adult Series List Great and Terrible Beauty June 2012 (By Author) by Libba Bray 1

3. Sirensong Young Adult Series List Great and Terrible Beauty June 2012 (By Author) By Libba Bray 1. A Great and Terrible Beauty Chains 2. Rebel Angels By Laurie Anderson 3. The Sweet Far Thing 1. Chains: Seeds of America 2. Forge The Faerie Wars Chronicles By Herbie Brennan Darkest Powers 1. Faerie Wars By Kelly Armstrong 2. Purple Emperor 1. The Summoning 3. Ruler of the Realm 2. The Awakening 4. Faerie Lord 3. The Reckoning The Gideon Trilogy Otherworld Series By Linda Buckley-Archer By Kelley Armstrong 1. The Time Travelers 1. Bitten 2. The Time Thief 2. Stolen 3. The Time Quake 3. Dime Store Magic 4. Industrial Magic Princess Diaries 5. Haunted By Meg Cabot 6. Broken 1. Princess Diaries 7. No Humans Involved 2. Princess in the Spotlight 8. Personal Demon 3. Princess in Love 9. Living with the dead 4. Princess in Waiting 10. Frostbitten 41/2. Project Princess 11. Waking the Witch 5. Princess in Pink 6. Princess in Training The Looking Glass Wars 61/2. The Princess Present By Frank Bennor 7. Party Princess 1. The Looking Glass Wars 71/2. Sweet Sixteen Princess 2. Seeing Redd 73/4. Valentine Princess 3. Arch Enemy 8. Princess on the Brink 9. Princess Mia Grey Griffin 10. Forever Princess By Derek Benz 11. Princess Lessons 1. Revenge of the Shadow King 12. Holiday Princess 2. Rise of the Black Wolf 13. Perfect Princess 3. Fall of the Templar Morganville Vampire A Modern Faerie Tale By Rachel Caine By Holly Black 1. Glass Houses 1. -

The Case of Muslims Tomasz Pelech

Shaping the Image of Enemy-Infidel in the Relations of Eyewitnesses and Participants of the First Crusade : The Case of Muslims Tomasz Pelech To cite this version: Tomasz Pelech. Shaping the Image of Enemy-Infidel in the Relations of Eyewitnesses and Participants of the First Crusade : The Case of Muslims. Archaeology and Prehistory. Université Clermont Auvergne; Uniwersytet Wroclawski, 2020. English. NNT : 2020CLFAL002. tel-03143783 HAL Id: tel-03143783 https://tel.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-03143783 Submitted on 17 Feb 2021 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. UNIWERSYTET WROCŁAWSKI WYDZIAŁ NAUK HISTORYCZNYCH I PEDAGOGICZNYCH INSTYTUT HISTORYCZNY / UNIVERSITÉ CLERMONT–AUVERGNE ÉCOLE DOCTORALE DES LETTRES, SCIENCES HUMAINES ET SOCIALES (ED 370) CENTRE D’HISTOIRE «ESPACES ET CULTURES» PRACA DOKTORSKA/THÈSE DE DOCTORAT Shaping the Image of Enemy-Infidel in the Relations of Eyewitnesses and Participants of the First Crusade: The Case of Muslims NAPISANA POD KIERUNKIEM/SOUS LA DIRECTION DES: Promotorzy/Directeurs: Prof. dr hab. Stanisław Rosik (Université de Wrocław) Prof. dr hab. Jean-Luc Fray (Université Clermont-Auvergne) Kopromotor/Cotuteur: Dr hab. Damien Carraz (Université Clermont-Auvergne) SKŁAD KOMISJI/MEMBRES DU JURY: Prof. dr hab. -

Adam Smith and Rousseau

Edited by Maria Pia Paganelli, Edited by Maria Pia Paganelli, Edited by Maria Pia Paganelli, Dennis C. Rasmussen Dennis C. Rasmussen Edinburgh Studies in Scottish Philosophy and Craig Smith Dennis C. Rasmussen and Craig Smith Series Editor: Gordon Graham ‘This excellent volume deepens our understanding of the relationship between the ideas and arguments of Smith and Rousseau, and succeeds in making it clear that our understanding Adam Smith of each of these hugely important philosophers depends to a significant extent on our understanding of the other.’ James Harris, University of St Andrews and Rousseau Looks at all aspects of the pivotal intellectual relationship between two key figures of the Adam Smith and Rousseau Enlightenment Ethics, Politics, Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712–1778) and Adam Smith (1723–1790) are two of the foremost thinkers of the European Enlightenment, thinkers who made seminal contributions to moral and political philosophy and who shaped some of the key concepts of modern Economics political economy. Though we have no solid evidence that they met in person, we do know that they shared many friends and interlocutors, particularly David Hume, who was Smith’s closest intellectual associate and who arranged for Rousseau’s stay in England in 1766. This collection brings together an international and interdisciplinary group of Adam Smith and Rousseau scholars to explore the key shared concerns of these two great thinkers in politics, philosophy, economics, history and literature. Maria Pia Paganelli is Associate Professor in the Department of Economics at Trinity University, San Antonio, Texas. Dennis C. Rasmussen is Associate Professor in the Department of Political Science at Tufts University. -

Saint: a Paradise Novel, 432 Pages

Saint: A Paradise Novel, 432 pages DOWNLOAD http://bit.ly/1mX1vqG http://goo.gl/REd7O http://www.goodreads.com/search?utf8=%E2%9C%93&query=Saint%3A+A+Paradise+Novel An assassin. The most effective killer in the world. And yet . Carl Strople struggles to retain fleeting memories that betray an even more ominous reality. He's been told part of the truth-but not all of it. Invasive techniques have stripped him of his identity and made him someone new--for this he is grateful. But there are some things they can't take from him. The love of a woman, unbroken loyalties to his past, the need for survival. From the deep woods of Hungary to the streets of New York, Saint takes you on a journey of betrayal in a world of government cover-ups, political intrigue, and one man's search for the truth. In the end, that truth will be his undoing. The Bookshelf Reviews, which gave this novel from Ted Dekker 5 out of 5 stars, stated, "Saint reads like The Bourne Identity [Robert Ludlum] meets The Matrix meets Mr. Murder [Dean Koontz]." DOWNLOAD http://wp.me/2DAMy http://scribd.com/doc/22098421/Saint-A-Paradise-Novel http://bit.ly/1zb7FQ0 Blessed Child , Ted Dekker, Bill Bright, Mar 10, 2006, Fiction, 351 pages. A famine relief expert, a Canadian Red Cross nurse, and an Ethiopian orphan experience the power of the Holy Spirit and ignite a spiritual revolution.. Showdown A Paradise Novel, Ted Dekker, Jan 3, 2006, Fiction, 384 pages. Welcome to Paradise. Epic battles of good and evil are happening all around us. -

Dialogic Portraits of Agnostic and Pragmatic

"NEITHER BELIEVER NOR INFIDEL” DIALOGIC PORTRAITS OF AGNOSTIC AND PRAGMATIC METHODOLOGIES IN MOBY-DICK AND CLAREL By Matthias Overos Hannah Wakefield Heather Palmer Assistant Professor Associate Professor (Chair) (Committee Member) Matthew Guy Associate Professor (Committee Member) “NEITHER BELIEVER NOR INFIDEL” DIALOGIC PORTRAITS OF AGNOSTIC AND PRAGMATIC METHODOLOGIES IN MOBY-DICK AND CLAREL By Matthias Overos A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the University of Tennessee at Chattanooga in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements of the Degree Master of Arts: English The University of Tennessee at Chattanooga Chattanooga, Tennessee May 2021 ii ABSTRACT Much scholarship is dedicated to Melville’s religious themes, and other scholarship carefully analyzes the innovative formal techniques used by Melville, such as biblical allusion, digressive essays, and philosophical musings imbedded in fiction. However, religious analysis often turns to biographical interpretations of Melville’s own beliefs, and formal analysis tends to highlight Melville’s idiosyncrasies rather than determine their function. This thesis uses the Bakhtinian concepts of dialogism and polyphony to show that Melville’s poetic techniques create open texts, allowing readers to freely engage with multiple religious views that are equally valid, though not equally beneficial. Anticipating the methodologies of agnosticism and pragmatism, Moby-Dick exemplifies an attitude of cheerful agnosticism, whereas Melville’s final major work, Clarel, exemplifies the frustrations of uncertainty. A primarily formal analysis allows scholars to view Melville both conforming and breaking out of expected religious attitudes in the nineteenth-century, without considering Melville a prophet of twentieth-century literary attitudes. iii DEDICATION For my wife and cat. For all the Sub-Sub-Librarians who, for some reason, find it worthwhile to study literature. -

The Blood-Red Crescent

++ Henry Garnett The Blood-Red Crescent SOPHIA INSTITUTE PRESS® Manchester, New Hampshire blrec_copyright_page.qxd 9/27/2007 10:17 AM Page 1 The Blood-Red Crescent was originally published in 1960 by Doubleday and Company, Inc., Garden City, New York. This 2007 edition by Sophia Institute Press® contains minor editorial revisions to correct infelicities in grammar and punctuation. Copyright © 2007 Sophia Institute Press® All rights reserved Cover artwork and design by Theodore Schluenderfritz Printed in the United States of America No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form, or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher, except by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages in a review. Sophia Institute Press® Box 5284, Manchester, NH 03108 1-800-888-9344 www.sophiainstitute.com Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Garnett, Henry, 1905– The blood-red crescent / Henry Garnett. p. cm. Summary: In 1570, as Christians throughout Europe unite in a Holy League to defeat Turkish invaders, fourteen-year-old Guido of Venice, Italy, leaves the safety of a monastery to serve on a ship his wealthy father has contributed and fights in the Battle of Lepanto. ISBN 978-1-933184-33-3 (pbk. : alk. paper) [1. Coming of age — Fiction. 2. Christianity — History — Fiction. 3. Islam — History — Fiction. 4. War — Fiction. 5. Lepanto, Battle of, Greece, 1571 — Fiction. 6. Family life — Italy — Fiction. 7. Italy — History — 1559–1789 — Fiction.] I. Title. PZ7.G18434Bl 2007 Fic]—dc22 2007033600 07 08 09 10 11 12 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 ++ This book is for Frances, Dominic, Mary Clare, and, last but not least, except in years, Mark Aelred, in the hope that they may sometimes think of “OY” +++ ++ Contents To Set the Scene . -

The Philosophical Publishing Life of David Hume

The Philosophical Publishing Life of David Hume GREGORY ERNEST BOUCHARD Department of History, McGill University, Montreal November, 2013 A thesis submitted to McGIll University in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Ph.D. in History © Gregory Ernest Bouchard, 2013 1 2 Table of Contents ABSTRACT ................................................................................................................................. 5 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS .......................................................................................................... 9 ABBREVIATIONS .................................................................................................................... 11 INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................................... 13 CHAPTER I: FROM TREATISE TO ESSAYS ..................................................................... 36 CHAPTER II: THE INTELLECTUAL AND MATERIAL CONSTRUCTION OF ESSAYS AND TREATISES ON SEVERAL SUBJECTS ..................................................................... 96 PART ONE ................................................................................................................................... 96 PART TWO.................................................................................................................................. 132 CHAPTER III: HUME IN THE CONVIVIAL SOCIETY OF EDINBURGH'S LITERATI ................................................................................................................................................. -

The Ultimate Fantasy Book List for Christian Teens and Adults (And Those Who Wish They Were)

The Ultimate Fantasy Book List for Christian Teens and Adults (and those who wish they were) You blazed through The Chronicles of Narnia, Redwall, and the Ranger's Apprentice. Now what? Rest assured your favorite books will probably stay your favorites for all your life, but there are great fantasy novels ahead! If your teen devours every fantasy novel you can find, or if you are looking for a book that will give you an escape for this world, here's your list! May it act as a map to guide you through new dangers, passed hungry trolls, and over the mountains to a safe haven. Check out this information first! I’ve included some of my “to read” list. If I haven’t read a book, I put a star after the author’s name. Not all books from all authors are listed. If you like an author, check out the rest of his/her books. While the books are organized by age groups, don’t hesitate to read up or down a level. Not all books are written by Christian authors. If there is something objectionable that I know about, I note them at the bottom of their section. The PDF comes with a handy box in front of each box for you to check off when you have finished reading it. There are currently 65 books on this list! But it’s not finished! I will continue to add books as more fantasy novels come to my attention. To get the updates, make sure to sign up for my newsletter.