Adam Smith and Rousseau

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

From Pig Farmer to Infidel: Hidden Identities, Diasporic Infertility, and Transethnic Kinship in Contemporary British Jewish Cinema

This is a repository copy of From Pig Farmer to Infidel: Hidden Identities, Diasporic Infertility, and Transethnic Kinship in Contemporary British Jewish Cinema. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/85099/ Version: Accepted Version Book Section: Sternberg, C (2016) From Pig Farmer to Infidel: Hidden Identities, Diasporic Infertility, and Transethnic Kinship in Contemporary British Jewish Cinema. In: Abrams, N and Lassner, P, (eds.) Hidden in Plain Sight: Jews and Jewishness in British Film, Television, and Popular Culture. Cultural Expressions of World War II: Interwar Preludes, Responses, Memory . Northwestern University Press , Evanston, Illinois , pp. 181-204. ISBN 978-0-8101-3282-5 Copyright © 2016 by Northwestern University Press. Published 2016. All rights reserved. This is an author produced version of a book chapter published in Hidden in Plain Sight: Jews and Jewishness in British Film, Television, and Popular Culture. Uploaded with permission from the publisher. Reuse Items deposited in White Rose Research Online are protected by copyright, with all rights reserved unless indicated otherwise. They may be downloaded and/or printed for private study, or other acts as permitted by national copyright laws. The publisher or other rights holders may allow further reproduction and re-use of the full text version. This is indicated by the licence information on the White Rose Research Online record for the item. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. -

A Bentham Bibliography

The Irish Journal o f Education 1977 xi 2 pp 8595 A BENTHAM BIBLIOGRAPHY Brian W Taylor* The University o f New Brunswick Works relating to Bentham s educational ideas are listed They are categorized under the following headings (i) Printed editions of the works of Bentham (n) General works on the history of the period which give special attention to Bentham and the utilitarians (in) Works of a general and philosophical nature which treat of Bentham and the philosophical radicals (iv) Bentham and the subject of law reform (v) Bentham and economics (vi) Bentham and education (vii) Bentham and philosophy (vm) Bentham and the poor (ix) Works on or by associates of Bentham which have some bearing on his work (x) Articles in the Dictionary of National Biography (xi) Miscellaneous works The prime concern of the author in compiling this bibliography has been to mclude those works which shed some light on the educational ideas of Jeremy Bentham Smce Bentham took a particularly wide view of what constituted education (referring to its ‘plastic power’), this has meant including some works which at first sight do not appear to be specifically ‘educational’ Nonetheless, they are important for the perspective they cast on Bentham’s educational thought Original manuscripts and translations of Bentham’s manuscripts are to be found m three locations By far the most important is the D M Watson Library at University College, London Information on this collection is to be found m Milne, A T , The catalogue of the manuscripts of Jeremy Bentham in the library -

The Risks of an Economic Agent: a Rousseauian Reading of Adam Smith

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Research Papers in Economics Rationality, preferences and irregular war/ 193 The risks of an economic agent: a Rousseauian reading of Adam Smith Jimena Hurtado P. Summary This article is a critical review of Adam Smiths notion of an economic agent. Using Jean Jacques Rousseaus arguments, I show the shortcomings of Smiths hypothesis regarding individuals economic behaviour within market society. The morals of sympathy, understood as a social theory and beyond the limitations Smith himself acknowledges, attempts to present the economic agent as a natural and unthreatening figure restricted to market transactions. A careful reading of Rousseau shows the historical character of Smiths construction, and thereby its failure to recognise the influence of social, cultural and economic development on the formation of this economic agent. Rousseau refuses the possibility of constructing economic theory based on this agent and denounces it as a way of justifying irresponsibility and tyranny. Two possible paths in economics are thus open: economics as an independent field of action or economics as a field regulated by politics. Keywords: Adam Smith, Jean Jacques Rousseau, economic agent, market society, economic analysis. JEL Classification: B1, B3, Z00. I would like to thank participants to PHAREs workshop on the Economic Agent for their questions and remarks on a first French version of this article. I had the opportunity of presenting a second version at the IVth Summer University of History of Economic Thought and Methodology Connaissance et Croyances en Histoire de la Pensée Economique, September 2001, Nice. -

9Th Grade 2016 Summer Reading All Forms

Hampton Christian Academy Upper School May 2016 Dear Parents, As we enter this summer, all of us—parents, students, and teachers—are excited about the well-earned break from the rigors of school. At the same time, however, we recognize that much hard-earned knowledge tends to slip away during the summer months unless we take measures to retain mental acuity. There is no question that one of the most valuable components to your student's academic success is a sustained pattern of reading. Students who are strong, avid readers are generally proficient students and competent test-takers. Hampton Christian Academy remains committed to doing all we can to develop our students’ reading skills and help them discover the life-long pleasure reading can bring to their lives. Each student in grades 7 - 11 is required to read a total of three books during the summer break. (Honors English students will have additional summer reading and writing assignments – see school website.) One of the three books has already been chosen for the student based on thematic content and grade level. This selected book will then be discussed the first week of school and a test will be given in class on the required book. This test will account for 50% of the student's summer reading test grade. An additional 25% will be earned by successfully completing a computerized Accelerated Reader quiz on a book from the grade level Accelerated Reader book list. AR quizzes consist of 10-20 questions focusing on reading comprehension. Students may drop by the school library on any Friday during the summer from 9 A.M. -

Rousseau and Smith: on Sympathy As a First Principle N6 PIERRE FORCE N7 12 at the Time

- --- -- ---- ------------------------- THINKING WITH ROUSSEAU From Machiavelli to Schmitt EDITED BY HELENA ROSENBLATT AND PAUL SCHWEIGERT a CAMBRIDGE ~ UNIVERSITY PRESS II4 DAVID SORKIN Human Race. As Dominique Bourel suggested, Rousseau was "an interlocutor with whom [Mendelssohn] was in dialogue his entire CHAPTER 6 life_,, Yet after the initial five year encounter he was a silent inter locutor in an unspoken and heretofore largely unrecognized Rousseau and Smith: On Sympathy as conversation. a First Principle Pierre Force In the work ofAdam Smith explicit references to Rousseau are few. The only extended treatment of Rousseau's views happened very early in Smith's career. In 1756 Smith published a critical review of the Discourse on the Origin ofInequality, just a few months after the publication of the book.' Smith scholars have generally seen the review as negative, but its ambiguous tone has allowed for diverging interpretations. I was one of the first com mentators to argue, in a 1997 article2 and in a 2003 book,3 that Rousseau was an essential interlocutor for Smith and that the discussion of first principles in the Theory ofMoral Sentiments and the Wealth ofNations appropriated key elements of Rousseau's philosophy (Keith Tribe's review described my analysis of the Rousseau-Smith connection as a "hitheno unwritten book") .4 I will structure this article as a critical discussion. I will summarize the claims I made at the time regarding how Smith's discussion of first principles was indebted to Rousseau. I will then summarize the objections made to these claims in reviews of my 2003 book, and will attempt to advance the discussion by responding to these objections. -

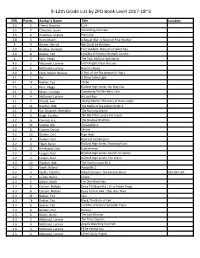

9-12Th Grade List by ZPD Book Level 2017-18~3

9-12th Grade List by ZPD Book Level 2017-18~3 ZPD Points Author's Name Title Location 3.2 5 Friend, Natasha Lush 3.5 7 Colasanti, Susan Something Like Fate 3.5 6 Hamilton, Virginia Plain City 3.8 3 Harry Mazer A Boy at War: A Novel of Pearl Harbor 4 4 Barnes, Derrick We Could be Brothers 4.0 5 Bradley, Kimberly For Freedom: Story of a French Spy 4.0 8 Dekker, Ted Lost Bks of History Series#5: Lunatic 4 3 Kern, Peggy The Test, Bluford High Series 4.0 5 McDaniel, Lurlene Until Angels Close my Eyes 4.0 5 McDaniel, Lurlene Heart to Heart 4.0 4 Peck, Robert Newton A Part of the Sky (sequel to Pigs ) 4.1 5 Avi A Place Called Ugly 4.1 14 Dekker, Ted Thr3e 4.1 3 Kern, Peggy Bluford High Series: No Way Out 4.1 4 Mazer, Lerangis Somebody Tell Me Who I Am 4.1 4 McDaniel, Lurlene Hit and Run 4.1 7 Rinaldi, Ann Taking Liberty: The Story of Oney Judge 4.1 12 Riordan, Rick The Battle of the Labyrinth Bk 4 4.1 9 Van Draanen, Wendelin The Running Dream 4.1 9 Voigt, Cynthia Tell Me if the Lovers are Losers 4.2 6 Cannon, A.E. The Shadow Brothers 4.2 13 Condie, Ally Crossed Bk 2 4.2 8 Cooner, Donna Skinny 4.2 10 Deuker, Carl High Heat 4.2 8 Deuker, Carl Heart of a Champion 4.2 4 Folan, Karyn Bluford High Series: Breaking Point 4.2 12 Honeyman, Kay Interference 4.2 3 Langan, Paul Bluford High Series: Search for Safety 4.2 3 Langan, Paul Bluford High Series: The Fallen 4.2 10 Riordan, Rick The Titan’s Curse Bk 3 4.2 10 Smith, Roland Above Bk 2 4.2 5 Yeatts, Tabatha Albert Einstein: The Miracle Mind 530.092 YEA 4.2 6 Lo'pez, Diana Choke 4.3 5 Albom, Mitch For -

Bentham and the Scots J.H

UCL Bentham Project Journal of Bentham Studies, vol. 7 (2004) Bentham and the Scots J.H. Burns Emeritus Professor of History, University College London What I have to offer here is not so much a paper as some scraps of paper. These represent, on the whole, the result of enquiries on which I have embarked at various times, but which I have not pursued rigorously to their appropriate conclusions. Nor does it now seem likely that I shall ever do so. To some extent, therefore, what I am presenting is an agenda of unfinished business, in the hope that some of the themes I have partially discussed will seem to others to be worth taking further. To this I must add that, even if this were a paper rather than a scrapbook, it would still be an imperfectly structured and incomplete paper. I shall present, to some extent, the beginning of the story and the end – though I shall, perversely, reverse their chronological order. The middle, however, will be all but completely missing. This is because my explorations, such as they have been, have never taken me beyond the threshold of Bentham’s Scotch Reform writings, which ought clearly to constitute the missing part of the story, falling as they do in that middle ground between the Bentham of the radical Enlightenment and the Bentham of philosophical radicalism. One more preliminary point before I begin – at the end.1 One reason for raising this subject at all is, I suggest, that there is something of a paradox to be considered. -

The Infidel.Mmsw

"THE INFIDEL" by Robert Carl Johnson Robert Carl Johnson 7510 E. Gem Shores Rd. Hayden Lake, ID 83835 (208) 772-9838 Cell (208) 818-6727 [email protected] FADE IN: INT. HEART MONITOR - DAY SUPER: "JANUARY 2ND. PRESENT DAY." A heartbeat's electrical line moves up and down across the screen - line movement goes erratic - goes flatline - steady SHRILL alarm sends an alert. FEMALE (V.O.) Code blue. Room 626. Code blue. Room 626. EXT. PARK - NIGHT (FLASHBACK) SUPER: "SEPTEMBER 11TH - 113 DAYS PRIOR." A speck of light flickers, grows brighter, reflects a child's tear-streaked cheeks. She and a group (all ages) share grief and pride and hold candles and small American Flags at a memorial. Multitudes of flowers and stuffed animals lay at a sign - "GOD BLESS AMERICA, OUR TROOPS AND TERRORISTS' VICTIMS." EXT. ANCIENT MIDDLE EAST CITY - DAY The sunrise reflects timeless beauty off spiral and domed ROOFS. A PRAYER CHANT's EERINESS seeps into AN ALLEY, shadowed and cobbled. Rats, ragged children, mangey cats and dogs scavenge trash-food. The CHANT NARROW STREET joins angry MURMURS as people scurry into a HUGE SQUARE, swallowed into a gathering horde as ANGRY SHOUTS and AUTOMATIC gun SHOTS rise to a frenzy and inflict the CHANT's merciless death. A woman of stature is unaffected by chaos. Her berka's fabric is of finest quality (no veil). Diamond dust glitters on manicured fingernails. 2. Her olive complexion is as smooth as melted Hagen Daz ice cream; radiant dark eyes as elusive as a frightened chameleon. But most striking are her lips; a slow twist stitches tight wetness of halves that men have died for since Adam and Eve. -

Walter Scott, James Hogg and Uncanny Testimony: Questions of Evidence and Authority Deirdre A

Walter Scott, James Hogg and Uncanny Testimony: Questions of Evidence and Authority Deirdre A. M. Shepherd PhD – The University of Edinburgh – 2009 Contents Preface i Acknowledgements ii Abstract iii Chapter One: Opening the Debate, 1790-1810 1 1.1 Walter Scott, James Hogg and Literary Friendship 8 1.2 The Uncanny 10 1.3 The Supernatural in Scotland 14 1.4 The Minstrelsy of the Scottish Border, 1802-3, The Lay of the Last Minstrel, 1805, and The Mountain Bard, 1807 20 1.5 Testimony, Evidence and Authority 32 Chapter Two: Experimental Hogg: Exploring the Field, 1810-1820 42 2.1 The Highlands and Hogg: literary apprentice 42 2.2 Nineteenth-Century Edinburgh: ‘Improvement’, Periodicals and ‘Polite’ Culture 52 2.3 The Spy, 1810 –1811 57 2.4 The Brownie of Bodsbeck, 1818 62 2.5 Winter Evening Tales, 1820 72 Chapter Three: Scott and the Novel, 1810-1820 82 3.1 Before Novels: Poetry and the Supernatural 82 3.2 Second Sight and Waverley, 1814 88 3.3 Astrology and Witchcraft in Guy Mannering, 1815 97 3.4 Prophecy and The Bride of Lammermoor, 1819 108 Chapter Four: Medieval Material, 1819-1822 119 4.1 The Medieval Supernatural: Politics, Religion and Magic 119 4.2 Ivanhoe, 1820 126 4.3 The Monastery, 1820 135 4.4 The Three Perils of Man, 1822 140 Chapter Five: Writing and Authority, 1822-1830 149 5.1 Divinity Matters: Election and the Supernatural 149 5.2 Redgauntlet, 1824 154 5.3 The Private Memoirs and Confessions of a Justified Sinner, 1824 163 Chapter Six: Scott: Reviewing the Fragments of Belief, 1824-1830 174 6.1 In Pursuit of the Supernatural 174 6.2 ‘My Aunt Margaret’s Mirror’ and ‘The Tapestried Chamber’ in The Keepsake, 1828 178 6.3 Letters on Demonology and Witchcraft, addressed to J. -

Young Adult Series List Great and Terrible Beauty June 2012 (By Author) by Libba Bray 1

3. Sirensong Young Adult Series List Great and Terrible Beauty June 2012 (By Author) By Libba Bray 1. A Great and Terrible Beauty Chains 2. Rebel Angels By Laurie Anderson 3. The Sweet Far Thing 1. Chains: Seeds of America 2. Forge The Faerie Wars Chronicles By Herbie Brennan Darkest Powers 1. Faerie Wars By Kelly Armstrong 2. Purple Emperor 1. The Summoning 3. Ruler of the Realm 2. The Awakening 4. Faerie Lord 3. The Reckoning The Gideon Trilogy Otherworld Series By Linda Buckley-Archer By Kelley Armstrong 1. The Time Travelers 1. Bitten 2. The Time Thief 2. Stolen 3. The Time Quake 3. Dime Store Magic 4. Industrial Magic Princess Diaries 5. Haunted By Meg Cabot 6. Broken 1. Princess Diaries 7. No Humans Involved 2. Princess in the Spotlight 8. Personal Demon 3. Princess in Love 9. Living with the dead 4. Princess in Waiting 10. Frostbitten 41/2. Project Princess 11. Waking the Witch 5. Princess in Pink 6. Princess in Training The Looking Glass Wars 61/2. The Princess Present By Frank Bennor 7. Party Princess 1. The Looking Glass Wars 71/2. Sweet Sixteen Princess 2. Seeing Redd 73/4. Valentine Princess 3. Arch Enemy 8. Princess on the Brink 9. Princess Mia Grey Griffin 10. Forever Princess By Derek Benz 11. Princess Lessons 1. Revenge of the Shadow King 12. Holiday Princess 2. Rise of the Black Wolf 13. Perfect Princess 3. Fall of the Templar Morganville Vampire A Modern Faerie Tale By Rachel Caine By Holly Black 1. Glass Houses 1. -

Journey, Rediscovery and Narrative

UNIVERSITY OF LONDON 50 INSTITUTE OF LATIN AMERICAN STUDIES RESEARCH PAPERS. Journey, Rediscovery and Narrative: British Travel Accounts of Argentina Ricardo Cicerchia JOURNEY, REDISCOVERY AND NARRATIVE: BRITISH TRAVEL ACCOUNTS OF ARGENTINA (1800-1850) Ricardo Cicerchia Institute of Latin American Studies 31 Tavistock Square London WC1H 9HA Ricardo Cicerchia is a researcher at CONICET-Universidad de Buenos Aires. In 1996/97 he was Shell Research Fellow at the Institute of Latin American Studies. Institute of Latin American Studies School of Advanced Study University of London British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 1 900039 20 6 ISSN 0957 7947 © Institute of Latin American Studies University of London, 1998 Journey, Rediscovery and Narrative: British Travel Accounts of Argentina (1800-1850) Readers are travellers, they move across lands belonging to someone else, like nomads poaching their way across fields they did not write, despoiling the wealth of Europe to enjoy it themselves.1 In August 1831 the Beagle was ready to sail for the coasts of South America. This expedition, like so many others, had a position open for someone who could double as an officer and as a naturalist. However, the obsessive Captain FitzRoy had another requirement. The suicide of the ship's previous commander had left him with disturbing premonitions. FitzRoy wanted a scientist, but - beyond that - he longed for a cultivated man with whom to pass the time in the isolated conditions that awaited them. FitzRoy hired a recent Cambridge graduate in Divinity who was also a frustrated student of medicine. -

The Case of Muslims Tomasz Pelech

Shaping the Image of Enemy-Infidel in the Relations of Eyewitnesses and Participants of the First Crusade : The Case of Muslims Tomasz Pelech To cite this version: Tomasz Pelech. Shaping the Image of Enemy-Infidel in the Relations of Eyewitnesses and Participants of the First Crusade : The Case of Muslims. Archaeology and Prehistory. Université Clermont Auvergne; Uniwersytet Wroclawski, 2020. English. NNT : 2020CLFAL002. tel-03143783 HAL Id: tel-03143783 https://tel.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-03143783 Submitted on 17 Feb 2021 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. UNIWERSYTET WROCŁAWSKI WYDZIAŁ NAUK HISTORYCZNYCH I PEDAGOGICZNYCH INSTYTUT HISTORYCZNY / UNIVERSITÉ CLERMONT–AUVERGNE ÉCOLE DOCTORALE DES LETTRES, SCIENCES HUMAINES ET SOCIALES (ED 370) CENTRE D’HISTOIRE «ESPACES ET CULTURES» PRACA DOKTORSKA/THÈSE DE DOCTORAT Shaping the Image of Enemy-Infidel in the Relations of Eyewitnesses and Participants of the First Crusade: The Case of Muslims NAPISANA POD KIERUNKIEM/SOUS LA DIRECTION DES: Promotorzy/Directeurs: Prof. dr hab. Stanisław Rosik (Université de Wrocław) Prof. dr hab. Jean-Luc Fray (Université Clermont-Auvergne) Kopromotor/Cotuteur: Dr hab. Damien Carraz (Université Clermont-Auvergne) SKŁAD KOMISJI/MEMBRES DU JURY: Prof. dr hab.