The Blood-Red Crescent

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tigers in Red Weather Have a Main Character? If So, Who Do You Think It Is?

TIGERSREADING GROUP GUIDEIN TIGERSRED IN WEATIGERS IN REDTHERWEATHER REDA Novel WEATHERBy LAizaNOKlaussmannVEL A NOVEL A NOVEL LIZAUSEKLAUSPDFSMANN LIZA KLAUSSMANN Little, Brown and Company New York Boston London Little, Brown and Company TigersInredWeather_TPtextF1.indd 1 New York Boston London 4/30/13 1:04 PM A C ONVERSATION WITH LIZA KLAUSSMANN Liza Klaussmann sits down with Antonina Jedrzejczak of Vogue.com What led you to write this book? I had always wanted to be a novelist and finally got around to being serious about it when I moved to London to do a master’s degree in creative writing in 2008. In terms of the idea for the book, my grand- mother, who died really quickly after I moved to London, was a very complicated person. Nick is definitely not her, but my grandmother partially inspired the character—the idea of someone complicated who can at once be glamorous and lovely to one person and be totally suppressive to someone else. What attracted you to writing about these three decades, starting in the forties, right after the Second World War, and ending in the late sixties, before you were born? In a lot of ways, it was this idea of people trying to be individuals post–World War II, when you were not really supposed to be individ- ualistic. The world was supposed to have been made whole—everyone was better and put on a happy face. It was a great time period to TigersInredWeather_TPtextF1.indd 3 4/30/13 1:04 PM NOID 2013-04-11 18:55:06 361 A conv4 er• sation Reading with GroupLiza Klaussmann Guide put characters like these in motion because the social barriers against achieving any kind of individualism or human agency were so strong. -

The Book of Common Prayer

The Book of Common Prayer and Administration of the Sacraments and Other Rites and Ceremonies of the Church Together with The Psalter or Psalms of David According to the use of The Episcopal Church Church Publishing Incorporated, New York Certificate I certify that this edition of The Book of Common Prayer has been compared with a certified copy of the Standard Book, as the Canon directs, and that it conforms thereto. Gregory Michael Howe Custodian of the Standard Book of Common Prayer January, 2007 Table of Contents The Ratification of the Book of Common Prayer 8 The Preface 9 Concerning the Service of the Church 13 The Calendar of the Church Year 15 The Daily Office Daily Morning Prayer: Rite One 37 Daily Evening Prayer: Rite One 61 Daily Morning Prayer: Rite Two 75 Noonday Prayer 103 Order of Worship for the Evening 108 Daily Evening Prayer: Rite Two 115 Compline 127 Daily Devotions for Individuals and Families 137 Table of Suggested Canticles 144 The Great Litany 148 The Collects: Traditional Seasons of the Year 159 Holy Days 185 Common of Saints 195 Various Occasions 199 The Collects: Contemporary Seasons of the Year 211 Holy Days 237 Common of Saints 246 Various Occasions 251 Proper Liturgies for Special Days Ash Wednesday 264 Palm Sunday 270 Maundy Thursday 274 Good Friday 276 Holy Saturday 283 The Great Vigil of Easter 285 Holy Baptism 299 The Holy Eucharist An Exhortation 316 A Penitential Order: Rite One 319 The Holy Eucharist: Rite One 323 A Penitential Order: Rite Two 351 The Holy Eucharist: Rite Two 355 Prayers of the People -

The Red Room H.G

THE RED ROOM H.G. Wells Gothic Digital Series @ UFSC FREE FOR EDUCATION The Red Room H.G. Wells (March 1896, The Idler) “I CAN assure you,” said I, “that it will take a very tangible ghost to frighten me.” And I stood up before the fire with my glass in my hand. “It is your own choosing,” said the man with the withered arm, and glanced at me askance. “Eight-and-twenty years,” said I, “I have lived, and never a ghost have I seen as yet.” The old woman sat staring hard into the fire, her pale eyes wide open. “Ay,” she broke in; “and eight-and-twenty years you have lived and never seen the likes of this house, I reckon. There’s a many things to see, when one’s still but eight-and-twenty.” She swayed her head slowly from side to side. “A many things to see and sorrow for.” I half suspected the old people were trying to enhance the spiritual terrors of their house by their droning insistence. I put down my empty glass on the table and looked about the room, and caught a glimpse of myself, abbreviated and broadened to an impossible sturdiness, in the queer old mirror at the end of the room. “Well,” I said, “if I see anything tonight, I shall be so much the wiser. For I come to the business with an open mind.” “It’s your own choosing,” said the man with the withered arm once more. I heard the faint sound of a stick and a shambling step on the flags in the passage outside. -

The Trouble with Paradise: Exploring Communities of Difference in Three American Novels

The Trouble With Paradise: Exploring Communities of Difference in Three American Novels by Blair Nosan The Trouble With Paradise: Exploring Communities of Difference in Three American Novels by Blair Nosan A thesis presented for the B. A. degree with Honors in The Department of English University of Michigan Spring 2008 © March 17, 2008 Blair Elizabeth Nosan Acknowledgements First and foremost, I would like to thank my advisor, Anne Herrmann, for her discerning eye and her vital input throughout this writing process. Scotti Parrish for her encouragement and willingness to devote time and concern to the entire thesis cohort. Her support has been indispensable. And Megan Sweeney for her inspiration, and her suggestion of resources—including two of the three novels I have analyzed as primary sources. I am indebted to Eileen Pollack, who was willing to meet with me and provide a personal interview, which was central to my analysis of her work. I have also benefited from the support of my roommates, Peter Schottenfels, Jacob Nathan, and Anna Bernstein, who have provided me with a respite, which was often greatly needed. To my friend Claire Smith who edited this essay in its entirety, and to Nicole Cohen, the 2008 honors cohort, and my sister Loren: these individuals devoted their time and effort to my project and I am very grateful. Finally, I want to thank my family, who not only supported my decision to remain at university for an extra year in order to pursue this very thesis, but also for providing me with emotional guidance throughout this rollercoaster of an experience. -

From Pig Farmer to Infidel: Hidden Identities, Diasporic Infertility, and Transethnic Kinship in Contemporary British Jewish Cinema

This is a repository copy of From Pig Farmer to Infidel: Hidden Identities, Diasporic Infertility, and Transethnic Kinship in Contemporary British Jewish Cinema. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/85099/ Version: Accepted Version Book Section: Sternberg, C (2016) From Pig Farmer to Infidel: Hidden Identities, Diasporic Infertility, and Transethnic Kinship in Contemporary British Jewish Cinema. In: Abrams, N and Lassner, P, (eds.) Hidden in Plain Sight: Jews and Jewishness in British Film, Television, and Popular Culture. Cultural Expressions of World War II: Interwar Preludes, Responses, Memory . Northwestern University Press , Evanston, Illinois , pp. 181-204. ISBN 978-0-8101-3282-5 Copyright © 2016 by Northwestern University Press. Published 2016. All rights reserved. This is an author produced version of a book chapter published in Hidden in Plain Sight: Jews and Jewishness in British Film, Television, and Popular Culture. Uploaded with permission from the publisher. Reuse Items deposited in White Rose Research Online are protected by copyright, with all rights reserved unless indicated otherwise. They may be downloaded and/or printed for private study, or other acts as permitted by national copyright laws. The publisher or other rights holders may allow further reproduction and re-use of the full text version. This is indicated by the licence information on the White Rose Research Online record for the item. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. -

Five Facets of the Pentagon in the Convent of Toni Morrison's Paradise

International Journal on Studies in English Language and Literature (IJSELL) Volume 4, Issue 3, March 2016, PP 1-9 ISSN 2347-3126 (Print) & ISSN 2347-3134 (Online) www.arcjournals.org Five Facets of the Pentagon in the Convent of Toni Morrison’s Paradise R.M.Prabha Ph.D. Scholar ManonmaniamSundaranar University Tirunelveli, Tamil Nadu [email protected] Abstract: Paradise is Toni Morrison’s seventh novel and is published in the year 1997. The structure of the novel is complex involving many characters in the historical background of Afro-American black people. The novel describes the story of a black community in 1990s in Oklahoma. The novel also discusses the way in which the community built and lived in a town called Ruby. The town was near a convent, in which five women lived together. They were happy and free from any form of oppression from the community. The novel Paradise is all about the story of the dispute between these two communities. The five women of the convent are different from each other and reach the convent for diverse reasons. The women differ from each other in their thought, deed and actions. Analysis of their personality reveals their varied nature and interestingly their traits match well with the five different types of the ‘Five Factor Model of Personality traits’ of human beings. This paper analyses the personality of these five women and discusses the unique way in which Toni Morrison has crafted these characters in such a way that it fits unerringly with the five common traits of the Personality model of human beings. -

Under the Blood-Red Sun Discussion Questions and Post-Reading Project

Under the Blood-Red Sun by Graham Salisbury Discussion Questions and Post-Reading Project BUY THE BOOK FOR YOUR CLASS! December 7, 1941 — 13-year-old Tomikazu Nakaji and his best friend, Billy Davis, are playing in a field near their homes in Hawaii when the Japanese launch a surprise attack on Pearl Harbor. As Tomi looks up at the sky and recognizes the Blood-Red Sun emblem on the amber fighter planes, he knows that his life has changed forever. His father and grandfather, both Japanese-Americans, are quickly arrested and taken to concentration camps. His mother loses her job because she is Japanese. Although Tomi feels frightened and ashamed of his native land, he is forced to become the man of the family. Under the Blood-Red Sun is an unforgettable tale of courage, survival and friendship. Buy the book from the Museum Store: http://store.nationalww2museum.org/under- the-blood-red-sun-pb.html Use the code PEARL75 at checkout to receive 20% off! Teachers wishing to order a class set of 12 or more books can receive a 40% discount by ordering through our wholesale department. Teachers can send in purchase orders via email to museumstore@nationalww2museum. org or fax at 504-527-6088. Shipping costs will be included on the invoice. Please allow three to four weeks for class sets to arrive. For more information please call 504-528-1944 x 284. DISCUSSION QUESTIONS: 1. The book is set in 1940s Oahu, Hawaii. Describe the Nakaji house and Tomi’s bedroom. How is it similar and different from your own? [Chapter 4] 2. -

The Red Circle

The Adventure of the Red Circle Arthur Conan Doyle This text is provided to you “as-is” without any warranty. No warranties of any kind, expressed or implied, are made to you as to the text or any medium it may be on, including but not limited to warranties of merchantablity or fitness for a particular purpose. This text was formatted from various free ASCII and HTML variants. See http://sherlock-holm.esfor an electronic form of this text and additional information about it. This text comes from the collection’s version 3.1. Table of contents PartOne.............................................................. 3 PartTwo.............................................................. 7 1 CHAPTER I. Part One ell,Mrs.Warren, I cannot see that you may be the most essential. You say that the man have any particular cause for uneasiness, came ten days ago and paid you for a fortnight’s nor do I understand why I, whose time board and lodging?” W is of some value, should interfere in the “He asked my terms, sir. I said fifty shillings a matter. I really have other things to engage me.” week. There is a small sitting-room and bedroom, So spoke Sherlock Holmes and turned back to the and all complete, at the top of the house.” great scrapbook in which he was arranging and “Well?” indexing some of his recent material. “He said, ‘I’ll pay you five pounds a week if I But the landlady had the pertinacity and also can have it on my own terms.’ I’m a poor woman, the cunning of her sex. She held her ground firmly. -

Black, Red, and White (The Circle Trilogy) by Ted Dekker

The Circle Series: Black, Red, and White (The Circle Trilogy) by Ted Dekker Ebook The Circle Series: Black, Red, and White (The Circle Trilogy) currently available for review only, if you need complete ebook The Circle Series: Black, Red, and White (The Circle Trilogy) please fill out registration form to access in our databases Download here >> Series:::: The Circle Trilogy (Book 1)+++Hardcover:::: 416 pages+++Publisher:::: Thomas Nelson Inc; Gph edition (December 29, 2009)+++Language:::: English+++ISBN-10:::: 1595548580+++ISBN-13:::: 978-1595548580+++Product Dimensions::::5.5 x 0.8 x 8.5 inches++++++ ISBN10 1595548580 ISBN13 978-1595548 Download here >> Description: More than a million fans have read The Circle Series. Now dive deeper and see it in a whole new light--introducing the visual edition of the epic novels Black, Red, and White.Thomas Hunter is a failed writer selling coffee at the Java Hut in Denver. Leaving work, he suddenly finds himself pursued by assailants through desert alleyways. Then a silent bullet clips his head . and his world goes black.From the blackness comes an amazing reality of another world where everything is somehow more real--and dangerous--than on Earth. In one world, hes a battle-scarred general commanding an army of primitive warriors. In the other, hes racing to outwit sadistic terrorists intent on creating global chaos through an unstoppable virus. Every time he falls asleep in one world, he awakens in the other. Yet in both, catastrophic disaster awaits him . may even be caused by him.Enter the Circle--an adrenaline-laced epic where dreams and reality collide. -

9Th Grade 2016 Summer Reading All Forms

Hampton Christian Academy Upper School May 2016 Dear Parents, As we enter this summer, all of us—parents, students, and teachers—are excited about the well-earned break from the rigors of school. At the same time, however, we recognize that much hard-earned knowledge tends to slip away during the summer months unless we take measures to retain mental acuity. There is no question that one of the most valuable components to your student's academic success is a sustained pattern of reading. Students who are strong, avid readers are generally proficient students and competent test-takers. Hampton Christian Academy remains committed to doing all we can to develop our students’ reading skills and help them discover the life-long pleasure reading can bring to their lives. Each student in grades 7 - 11 is required to read a total of three books during the summer break. (Honors English students will have additional summer reading and writing assignments – see school website.) One of the three books has already been chosen for the student based on thematic content and grade level. This selected book will then be discussed the first week of school and a test will be given in class on the required book. This test will account for 50% of the student's summer reading test grade. An additional 25% will be earned by successfully completing a computerized Accelerated Reader quiz on a book from the grade level Accelerated Reader book list. AR quizzes consist of 10-20 questions focusing on reading comprehension. Students may drop by the school library on any Friday during the summer from 9 A.M. -

Adam Bede by George Eliot Book One Chapter I the Workshop with a Single Drop of Ink for a Mirror, the Egyptian Sorcerer Undertak

Adam Bede by George Eliot Book One Chapter I The Workshop With a single drop of ink for a mirror, the Egyptian sorcerer undertakes to reveal to any chance comer far-reaching visions of the past. This is what I undertake to do for you, reader. With this drop of ink at the end of my pen, I will show you the roomy workshop of Mr. Jonathan Burge, carpenter and builder, in the village of Hayslope, as it appeared on the eighteenth of June, in the year of our Lord 1799. The afternoon sun was warm on the five workmen there, busy upon doors and window-frames and wainscoting. A scent of pine-wood from a tentlike pile of planks outside the open door mingled itself with the scent of the elder-bushes which were spreading their summer snow close to the open window opposite; the slanting sunbeams shone through the transparent shavings that flew before the steady plane, and lit up the fine grain of the oak panelling which stood propped against the wall. On a heap of those soft shavings a rough, grey shepherd dog had made himself a pleasant bed, and was lying with his nose between his fore-paws, occasionally wrinkling his brows to cast a glance at the tallest of the five workmen, who was carving a shield in the centre of a wooden mantelpiece. It was to this workman that the strong barytone belonged which was heard above the sound of plane and hammer singing-- Awake, my soul, and with the sun Thy daily stage of duty run; Shake off dull sloth.. -

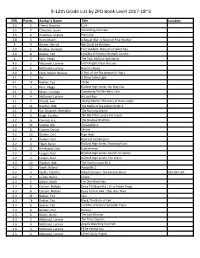

9-12Th Grade List by ZPD Book Level 2017-18~3

9-12th Grade List by ZPD Book Level 2017-18~3 ZPD Points Author's Name Title Location 3.2 5 Friend, Natasha Lush 3.5 7 Colasanti, Susan Something Like Fate 3.5 6 Hamilton, Virginia Plain City 3.8 3 Harry Mazer A Boy at War: A Novel of Pearl Harbor 4 4 Barnes, Derrick We Could be Brothers 4.0 5 Bradley, Kimberly For Freedom: Story of a French Spy 4.0 8 Dekker, Ted Lost Bks of History Series#5: Lunatic 4 3 Kern, Peggy The Test, Bluford High Series 4.0 5 McDaniel, Lurlene Until Angels Close my Eyes 4.0 5 McDaniel, Lurlene Heart to Heart 4.0 4 Peck, Robert Newton A Part of the Sky (sequel to Pigs ) 4.1 5 Avi A Place Called Ugly 4.1 14 Dekker, Ted Thr3e 4.1 3 Kern, Peggy Bluford High Series: No Way Out 4.1 4 Mazer, Lerangis Somebody Tell Me Who I Am 4.1 4 McDaniel, Lurlene Hit and Run 4.1 7 Rinaldi, Ann Taking Liberty: The Story of Oney Judge 4.1 12 Riordan, Rick The Battle of the Labyrinth Bk 4 4.1 9 Van Draanen, Wendelin The Running Dream 4.1 9 Voigt, Cynthia Tell Me if the Lovers are Losers 4.2 6 Cannon, A.E. The Shadow Brothers 4.2 13 Condie, Ally Crossed Bk 2 4.2 8 Cooner, Donna Skinny 4.2 10 Deuker, Carl High Heat 4.2 8 Deuker, Carl Heart of a Champion 4.2 4 Folan, Karyn Bluford High Series: Breaking Point 4.2 12 Honeyman, Kay Interference 4.2 3 Langan, Paul Bluford High Series: Search for Safety 4.2 3 Langan, Paul Bluford High Series: The Fallen 4.2 10 Riordan, Rick The Titan’s Curse Bk 3 4.2 10 Smith, Roland Above Bk 2 4.2 5 Yeatts, Tabatha Albert Einstein: The Miracle Mind 530.092 YEA 4.2 6 Lo'pez, Diana Choke 4.3 5 Albom, Mitch For