Advisory Board Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual Report

COUNCIL ON FOREIGN RELATIONS ANNUAL REPORT July 1,1996-June 30,1997 Main Office Washington Office The Harold Pratt House 1779 Massachusetts Avenue, N.W. 58 East 68th Street, New York, NY 10021 Washington, DC 20036 Tel. (212) 434-9400; Fax (212) 861-1789 Tel. (202) 518-3400; Fax (202) 986-2984 Website www. foreignrela tions. org e-mail publicaffairs@email. cfr. org OFFICERS AND DIRECTORS, 1997-98 Officers Directors Charlayne Hunter-Gault Peter G. Peterson Term Expiring 1998 Frank Savage* Chairman of the Board Peggy Dulany Laura D'Andrea Tyson Maurice R. Greenberg Robert F Erburu Leslie H. Gelb Vice Chairman Karen Elliott House ex officio Leslie H. Gelb Joshua Lederberg President Vincent A. Mai Honorary Officers Michael P Peters Garrick Utley and Directors Emeriti Senior Vice President Term Expiring 1999 Douglas Dillon and Chief Operating Officer Carla A. Hills Caryl R Haskins Alton Frye Robert D. Hormats Grayson Kirk Senior Vice President William J. McDonough Charles McC. Mathias, Jr. Paula J. Dobriansky Theodore C. Sorensen James A. Perkins Vice President, Washington Program George Soros David Rockefeller Gary C. Hufbauer Paul A. Volcker Honorary Chairman Vice President, Director of Studies Robert A. Scalapino Term Expiring 2000 David Kellogg Cyrus R. Vance Jessica R Einhorn Vice President, Communications Glenn E. Watts and Corporate Affairs Louis V Gerstner, Jr. Abraham F. Lowenthal Hanna Holborn Gray Vice President and Maurice R. Greenberg Deputy National Director George J. Mitchell Janice L. Murray Warren B. Rudman Vice President and Treasurer Term Expiring 2001 Karen M. Sughrue Lee Cullum Vice President, Programs Mario L. Baeza and Media Projects Thomas R. -

Seymour Weiss Papers

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt0870316q No online items Register of the Seymour Weiss papers Finding aid prepared by David Jacobs Hoover Institution Library and Archives © 2016 434 Galvez Mall Stanford University Stanford, CA 94305-6003 [email protected] URL: http://www.hoover.org/library-and-archives Register of the Seymour Weiss 99004 1 papers Title: Seymour Weiss papers Date (inclusive): 1943-1998 Collection Number: 99004 Contributing Institution: Hoover Institution Library and Archives Language of Material: English Physical Description: 27 manuscript boxes, 1 oversize box(11.6 Linear Feet) Abstract: The papers document Seymour Weiss's long career as an analyst at the U.S. Department of State. Working closely with his counterparts in the Department of Defense, Weiss specialized in the fields of nuclear strategy and arms control. The bulk of his papers consist of correspondence, memoranda, photographs, and reports, among which are numerous studies of the strength of the Soviet military and analyses of treaties such as the Strategic Arms Limitation Treaties (SALT I and II). Creator: Weiss, Seymour Hoover Institution Library & Archives Access The collection is open for research; materials must be requested at least two business days in advance of intended use. Publication Rights For copyright status, please contact the Hoover Institution Library & Archives. Acquisition Information Acquired by the Hoover Institution Library & Archives in 1999. Preferred Citation [Identification of item], Seymour Weiss papers, [Box no., Folder no. or title], Hoover Institution Library & Archives. 1925 May Born, Chicago, Illinois 15 1968-1969 Director, Office of Strategic Research and Intelligence, U.S. Department of State 1972-1973 Deputy Director, Policy Planning Staff, U.S. -

Stephen Friedman January 27, 2010

As Revised United States House of Representatives Committee on Oversight and Government Reform “Factors Affecting Efforts to Limit Payments to AIG Counterparties” Prepared Testimony of Stephen Friedman January 27, 2010 Mr. Chairman, Ranking Member Issa, and Members of the Committee, I am here today because of my great respect for Congress and the essential role that it plays in the United States Government. It was my recent privilege to serve my country in the Executive Branch as Assistant to the President for Economic Policy and Director of the National Economic Council from 2002 to 2004, and as Chairman of the President’s Foreign Intelligence Advisory Board from 2006 to 2009, and I developed a renewed appreciation of our Constitutional system of checks and balances. Despite my recognition of the importance of the Committee’s inquiry, I cannot provide the Committee with any insight into the principal subject of today’s hearing—the transaction that paid AIG’s credit default swap counterparties at par. The questions raised about these transactions reflect understandable confusion about the role that a Reserve Bank’s Chairman and Board of Directors play in a Reserve Bank’s operations. Consistent with the structure created by the Federal Reserve Act, the Board of Directors of the New York Federal Reserve Bank has no role in the regulation, supervision, or oversight of banks, bank holding companies, or other financial institutions. Such responsibilities are instead carried out by the officers of the New York Federal Reserve Bank acting at the direction of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System here in Washington. -

Neoconservatism: Origins and Evolution, 1945 – 1980

Neoconservatism: Origins and Evolution, 1945 – 1980 Robert L. Richardson, Jr. A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History. Chapel Hill 2009 Approved by, Michael H. Hunt, Chair Richard Kohn Timothy McKeown Nancy Mitchell Roger Lotchin Abstract Robert L. Richardson, Jr. Neoconservatism: Origins and Evolution, 1945 – 1985 (Under the direction of Michael H. Hunt) This dissertation examines the origins and evolution of neoconservatism as a philosophical and political movement in America from 1945 to 1980. I maintain that as the exigencies and anxieties of the Cold War fostered new intellectual and professional connections between academia, government and business, three disparate intellectual currents were brought into contact: the German philosophical tradition of anti-modernism, the strategic-analytical tradition associated with the RAND Corporation, and the early Cold War anti-Communist tradition identified with figures such as Reinhold Niebuhr. Driven by similar aims and concerns, these three intellectual currents eventually coalesced into neoconservatism. As a political movement, neoconservatism sought, from the 1950s on, to re-orient American policy away from containment and coexistence and toward confrontation and rollback through activism in academia, bureaucratic and electoral politics. Although the neoconservatives were only partially successful in promoting their transformative project, their accomplishments are historically significant. More specifically, they managed to interject their views and ideas into American political and strategic thought, discredit détente and arms control, and shift U.S. foreign policy toward a more confrontational stance vis-à-vis the Soviet Union. -

Press 6 May 2021 Frieze New York, First Live Art Fair in a Year, Kicks

The New York Times Frieze New York, First Live Art Fair in a Year, Kicks Off at the Shed Will Heinrich and Martha Schwendener 6 May 2021 Frieze New York, First Live Art Fair in a Year, Kicks Off at the Shed Our critics toured more than 60 booths — a sight for art-starved eyes. Here are 16 highlights to catch, in person or virtually. Image: “Who Taught You to Love?” by Hank Willis Thomas is part of a tribute to the Vision & Justice Project, in the Frieze New York fair at the Shed. Credit: Krista Schlueter for The New York Times. The colossal white tent on Randalls Island — the one that occasionally threatened to uplift and blow away — is gone, along with the frenetic ferry rides up and down the East River. But Frieze is back, the first live art fair returning to New York after more than a year. This year’s edition, taking place Wednesday to Sunday, is inside the Shed, the performing arts center on the Far West Side at Hudson Yards. It includes only 64 commercial galleries — as opposed to nearly 200 in 2019 — though some international exhibitors from Buenos Aires, Brazil and London are represented. But there is plenty of work worth seeing, spread over more than three double-height levels. All necessary health precautions are being observed, but unless you’ve made prior arrangements, you may not be able to attend in person: Tickets are already sold out. What remains is a waiting list and an extensive virtual Viewing Room with more than 160 international galleries, which you can visit free through May 14. -

John Birch Leo Cherne

The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, U.S. Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material. If a user makes a request for, or later uses a photocopy or reproduction (including handwritten copies) for purposes in excess of fair use, that user may be liable for copyright infringement. Users are advised to obtain permission from the copyright owner before any re-use of this material. Use of this material is for private, non-commercial, and educational purposes; additional reprints and further distribution is prohibite@j. Copies are not for resale. All other rights are reserved. For tither information, contact Director, Hoover Institution Library~nd Archives, Stanford University, Stanford, CA 94305-6010. c: n rn ::D © Board of Trustees of the?Iand Stanford Jr. University. H ~ ;. ; o FIRinG Line GUESTS: JOHN BIRCH LEO CHERNE SUBJECT: "SOVIET WORDS AND DEEDS: AFGHANISTAN" #759 SOUTHERN EDUCATIONAL COMMUNICATIONS ASSOCIATION SECA PRESENTS ~ FIRinG Line HOST: WILLIAM F. BUCKLEY JR. GUESTS: JOHN BIRCH The FIRING LINE television series is a production of the Southern Educational LEO CHERNE Communications Association, PO Box 5966, Columbia, SC 29250 and is transmitted through the facilities of the Public Broadcasting Service. FIRING SUBJECT: ·SOVIET WORDS AND DEEDS: AFGHANISTAN. LINE can be seen and heard each week through public television and radio stations throughout the country. Check your local newspapers for channel and time in your area. FIRING LINE is produced and directed by WARREN STEIBEL This is a transcript of the Firing Line program taped in New York City on December 3, 1987, and telecast later by PBS. -

Wal Mart Stores, Inc

WAL#MART STORES, INC. Bentonville, Arkansas 72716 (501) 273-4000 www.wal-mart.com NOTICE OF ANNUAL MEETING OF SHAREHOLDERS To Be Held June 2, 2000 Please join us for the 2000 Annual Meeting of Shareholders of Wal-Mart Stores, Inc. The meeting will be held on Friday, June 2, 2000, at 9:00 a.m. in Bud Walton Arena, University of Arkansas, Fayetteville, Arkansas. Pre-meeting activities start at 7:00 a.m. The purposes of the meeting are: (1) Election of directors; (2) To act on a shareholder proposal described on pages 16 to 18 of the Proxy Statement; and (3) Any other business that may properly come before the meeting. You must own shares at the close of business on April 7, 2000, to vote at the meeting. If you plan to attend, please bring the Admittance Slip on the back cover. Regardless of whether you will attend, please vote by signing, dating and returning the enclosed proxy card or by telephone or online, as described on page 1. Voting in these ways will not prevent you from voting in person at the meeting. By Order of the Board of Directors Robert K. Rhoads Secretary Bentonville, Arkansas April 14, 2000 WAL#MART STORES, INC. Bentonville, Arkansas 72716 (501) 273-4000 www.wal-mart.com PROXY STATEMENT This Proxy Statement is being mailed beginning April 14, 2000, in connection with the solicitation of proxies by the Board of Directors of Wal-Mart Stores, Inc., a Delaware corporation, for use at the Annual Meeting of Shareholders. The meeting will be held in Bud Walton Arena, University of Arkansas, Fayetteville, Arkansas, on Friday, June 2, 2000, at 9:00 a.m. -

The Ukrainian Weekly 1983, No.9

www.ukrweekly.com lished by the Ukrainian National Association Inc.. a fraternal non-profit association| rainianWeei:! Ї Voi. LI mNo. 9 THE UKRAINIAN WEEKLY SUNDAY. FEBRUARY 27.1983 25 cents Feodor Fedorenko ordered deported Yosyp Tereiia arrested Solicitor General's office that the Has 10 days government did not appeal the case by Dr. Roman Solchanyk because, in his view, Mr. Fedorenko to file appeal "may be the unfortunate victim of MUNICH - Western news agencies innocently mistaken identification/' in Moscow, quoting dissident sources, HARTFORD, Conn. - Feodor Mr. Ryan was subsequently to reverse have reported that Yosyp Tereiia, an Fedorenko, 75, who was stripped of his himself. He was named head of the OSI activist of the banned Ukrainian Catho U.S. citizenship in 1981 for withholding in 1980. lic (Uniate) Church, has been arrested in information about his wartime activi On June 28, 1979, a U.S. Court of Ukraine. ties when applying to enter the country Appeals reversed the lower court's The agencies added that last Septem after World War II, was ordered de decision, and directed the District ber Mr. Tereiia and four others formed ported on February 23, reported CBS Court to cancel the defendant's certifi an Initiative Group for the Defense of News. cate of naturalization. the Rights of Believers and the Church The ruling by an Immigration Court to campaign for the legalization of the came nearly 21 months after the case The Court of Appeals decision was Ukrainian Church, which was liqui was first brought before the court by the upheld by the Supreme Court on Ja dated in 1946 after the Soviet occupa Justice Department's Office of Special nuary 21, 1981. -

MS-603: Rabbi Marc H. Tanenbaum Collection, 1945-1992

MS-603: Rabbi Marc H. Tanenbaum Collection, 1945-1992. Series D: International Relations Activities. 1961-1992 Box 61, Folder 1, International Rescue Committee, December 1978. 3101 Clifton Ave, Cincinnati, Ohio 45220 (513) 221-1875 phone, (513) 221-7812 fax americanjewisharchives.org · ! .,. -REF 12/0o/78 · a~!J!'."OV. ('i-M ~ .REF: Ros:::::-: BL..~Tr C:L=:.;:3.: · De. >""'- 'fl./ .. .. ANB . DCM POL, SA3 . CONS REF4 1 CHRON ,;;.C:cf .,/J1V AMEMBASSY BANGKOK SECSTATE \·J.i:\.SHDC, .IMMEDIATE u9-· INFO US MISSION GENEVJ>., IMMEDIATE r? ·~ · .,,.--~-··.. ~ AL"!EMBAS SY BONN ~- . AHRMBASS Y PARIS ·+· {tv..Sc.)~J · AME.MBASSY OTTAWA . · ..,· AflENBASSY CANBERRA ·ANEMBASSY LONDON . A.."'!EMBASSY MANILA AMEMBASSY JAKARTA · Af!CONSUL HONG KONG AMEHB-2\SSY SINGAPORE . USLO PEKHJG ·'··· ::t(· · ANEHBASSY TAIPEI _., ,, AHEMBASSY KUALA LUNPUR CINCPAC HONOLULU HAWAII AMEHBASSY SEOUL ANEMBASSY ~YO AHEHBASSY WELLING'ION GE~iEVA ALSO FOR LOWMAN 'EO 12 065 : NA TAGS: SREF SUBJ: LAND REFUGEES IN THAILAND. DIMENSIO~S OF THE PROBLEM 1. WE HAVE STRESSED .THAT THE GENEVA CQNSULTATION SHOULD ADDRESS THE ._PROBLEM OF LA.""JD . REFUGEES AS WELL AS THE CRITICAL BOAT REFUGEE EMERGENCY.. W1!i i1£T ri:-sz:E: ~THE. STATISTICAL UPDATE ON LAND REFUGEES PROVIDED· BELOW WILL BE USEFUL FOR. REFERENCE DURING THE CONSULTATION. 2. LA..~D REFUGEE POPULATION IN. THAILA.1'1D IS 'NON OVER 135, 000 (120, 000 "HIGHLA..'WERS Al.~D ETHNIC LAO · FRm1 LAOS, 15, 000 REFUGEES FROM CAHBODIA A.lllD 1, 500 VIET~ANESE REFUGEE_S FROM LAOS) • . THE L..~ND RE.FUGEE ·POPULATION !Ll:\.S INCREASED BY ABOUT 40,000 IN THE FIRST 11 MONTHS OF 1978 (EVEN .AFTER . -

Congressional Record—Senate S986

S986 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD Ð SENATE January 25, 1999 CONSOLIDATED REPORT OF EXPENDITURE OF FOREIGN CURRENCIES AND APPROPRIATED FUNDS FOR FOREIGN TRAVEL BY MEMBERS AND EMPLOYEES OF THE U.S. SENATE, UNDER AUTHORITY OF SEC. , P.L. 95±384Ð22 U.S.C. 1754(b), COMMISSION ON SECURITY AND COOPERATION IN EUROPE FOR TRAVEL FROM JULY 1 TO SEPT. 30, 1998 Per diem Transportation Miscellaneous Total U.S. dollar U.S. dollar U.S. dollar U.S. dollar Name and country Name of currency Foreign equivalent Foreign equivalent Foreign equivalent Foreign equivalent currency or U.S. currency or U.S. currency or U.S. currency or U.S. currency currency currency currency Elizabeth Campbell: United States .............................................................................................. Dollar ................................................... .................... .................... .................... 2,215.32 .................... .................... .................... 2,215.32 Bosnia-Herzegovina ..................................................................................... Dollar ................................................... .................... 824.00 .................... .................... .................... .................... .................... 824.00 Orest Deychakiwsky: United States .............................................................................................. Dollar ................................................... .................... .................... .................... 2,860.46 ................... -

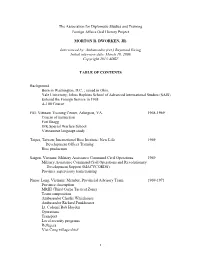

The Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History Project MORTON R. DWORKEN, JR. Interviewed

The Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History Project MORTON R. DWORKEN, JR. Interviewed by: Ambassador (ret.) Raymond Ewing Initial interview date: March 10, 008 Copyright 013 ADST TABLE OF CONTENTS Background Born in ashington, D.C. $ raised in Ohio. Yale University$ (ohns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies (SAIS) ,ntered the Foreign Service in 19.8 A0111 Course FSI2 3ietnam Training Center, Arlington, 3A. 19.8019.9 Course of instruction Fort Bragg (F4 Special arfare School 3ietnamese language study Taipei, Taiwan$ International Rice Institute$ New 8ife 19.9 Development Officer Training Rice production Saigon, 3ietnam2 9ilitary Assistance Command Civil Operations 19.9 9ilitary Assistance Command Civil Operations and Revolutionary Development Support (9AC3CORDS) Province supervisory team training Phuoc 8ong, 3ietnam2 9ember, Provincial Advisory Team 19.901971 Province description 9RIII (Third Corps Tactical Zone) Team composition Ambassador Charlie hitehouse Ambassador Richard Funkhouser 8t. Colonel Bob Hayden Operations Transport 8ocal security programs Refugees 3iet Cong village chief 1 8iving conditions 3isits to Saigon Personal weapons 9ontagnards Assistance to Catholic Sisters Rattan production Hamlet ,valuation System (H,S) Tet Province Development Plan Relations with 3ietnamese army Hawthorne (Hawk) 9ills Ambassador Sam Berger General Abrams Counter0Insurgency Assessment of US03ietnam endeavor 3ientiane, 8aos2 Special Assistant for Political09ilitary Affairs 197101973 Nickname2 -

1970S Outline I. Richard Milhous Nixon

American History 1970s Outline I. Richard Milhous Nixon (1969-1974) –Republican A. Born Yorba Linda, California –College and WWII B. Machiavellian Political Career –House, Senate, and VP (Checkers) C. Speeches -“Bring Us Together” and the “Great Silent Majority” D. President Nixon Fun Facts II. Presidency of Richard Nixon A. Foreign Policy –Dr. Henry Kissinger –NSA (1969-1974) and Secretary of State (1973-1977) 1. Vietnam War –“Peace with Honor” 2. Moon Landing –July 20, 1969 –Neil Armstrong, Buzz Aldrin, and Michael Collins 3. Nixon and Communist Countries A. Détente –relaxation of tensions with communist nations B. Triangular Diplomacy –playing the communist countries against each other C. Actions with communist countries 1. Ping Pong 2. Visited the People’s Republic of China –February 21-28, 1972 3. Visited Soviet Union –May 22 – May 30, 1972 –Leonid Brezhnev (1964-82) A. SALT (Strategic Arms Limitation Talks) Treaty 4. Vietnam –Cease-fire –January 27, 1973 4. Middle East A. LBJ and the Six Day War June 5-10, 1967 –Israel vs. Egypt, Syria, and Jordan 1. US support –send fighters to Israel 2. Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) –Yasir Arafat B. Yom Kippur War –October 6, 1973 – September 1, 1975 –Egypt & Syria vs. Israel 1. US support –Operation Nickel Grass –airlifted $2 billion in supplies to Israel 2. Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) 5. Chile –Operation Condor -helped to overthrow President Salvador Allende B. Domestic Policy -New Federalism –“E-Challenges” 1. Economic Crisis –stagflation A. Causes –Vietnam spending, Vietnam War spending, tax cuts, oil prices up B. Solution –New Economic Policy –90 freeze on prices and wages 2.