Mutiny in the Portuguese Indian Army

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sources of Maratha History: Indian Sources

1 SOURCES OF MARATHA HISTORY: INDIAN SOURCES Unit Structure : 1.0 Objectives 1.1 Introduction 1.2 Maratha Sources 1.3 Sanskrit Sources 1.4 Hindi Sources 1.5 Persian Sources 1.6 Summary 1.7 Additional Readings 1.8 Questions 1.0 OBJECTIVES After the completion of study of this unit the student will be able to:- 1. Understand the Marathi sources of the history of Marathas. 2. Explain the matter written in all Bakhars ranging from Sabhasad Bakhar to Tanjore Bakhar. 3. Know Shakavalies as a source of Maratha history. 4. Comprehend official files and diaries as source of Maratha history. 5. Understand the Sanskrit sources of the Maratha history. 6. Explain the Hindi sources of Maratha history. 7. Know the Persian sources of Maratha history. 1.1 INTRODUCTION The history of Marathas can be best studied with the help of first hand source material like Bakhars, State papers, court Histories, Chronicles and accounts of contemporary travelers, who came to India and made observations of Maharashtra during the period of Marathas. The Maratha scholars and historians had worked hard to construct the history of the land and people of Maharashtra. Among such scholars people like Kashinath Sane, Rajwade, Khare and Parasnis were well known luminaries in this field of history writing of Maratha. Kashinath Sane published a mass of original material like Bakhars, Sanads, letters and other state papers in his journal Kavyetihas Samgraha for more eleven years during the nineteenth century. There is much more them contribution of the Bharat Itihas Sanshodhan Mandal, Pune to this regard. -

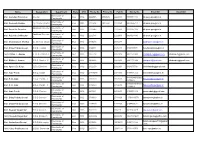

Name Designation Department State STD Phone No Phone No Fax No Mobile No Email ID1 Email ID2 Directorate of Shri

Name Designation Department State STD Phone No Phone No Fax No Mobile No Email ID1 Email ID2 Directorate of Shri. Gurudas Pilarnekar Director Goa 0832- 2222586 2432826 2222863 9763554136 [email protected] Panchayats Directorate of Shri. Dashrath Redkar Dy.Director (North) Goa 0832- 2222586 2432550 2222863 9422456712 [email protected] Panchayats Additional Director - Directorate of Shri. Gopal A. Parsekar Goa 0832- 2222586 2222863 9923267335 [email protected] I Panchayats Additional Director - Directorate of Shri. Rajendra D Mirajkar Goa 0832- 2222586 2222863 9423324140 [email protected] II Panchayats Directorate of Shri. Chandrakant Shetkar Dy. Director (South) Goa 0832- 2715278 2794277 [email protected] Panchayats Directorate of Shri. Uday Prabhudessai B.D.O. Tiswadi Goa 0832- 2426481 2426481 9764480571 [email protected] Panchayats Directorate of Shri. Bhiku. L. Gawas B. D. O. Bardez - I Goa 0832- 2262206 2262206 9421151048 [email protected] [email protected] Panchayats Directorate of Shri. Bhiku. L. Gawas B.D.O. Bardez - II Goa 0832- 2262206 2262206 9421151048 [email protected] [email protected] Panchayats Directorate of Smt. Apurva D. Karpe B.D.O.Bicholim Goa 0832- 2362103 2362103 9423055791 [email protected] Panchayats Directorate of Shri. Amir Parab B.D.O. Sattari Goa 0832- 23734250 2374056 9158051212 [email protected] Panchayats Directorate of 8888688909/839 Shri. P. K. Naik B.D.O. Ponda - I Goa 0832- 2312129 2312019 [email protected] Panchayats 0989449 Directorate of 8888688909/839 Shri. P. K. Naik B.D.O. Ponda - II Goa 0832- 2312129 2312019 [email protected] Panchayats 0989449 Directorate of Shri. -

Official Gazette Government of Go~ Daman and Diu

.\ REGD. GOA 5\ Panaji, 2nd February, 197B (Magha 13, lB99) SER!ES '" No.' 44 OFFICIAL GAZETTE GOVERNMENT OF GO~ DAMAN AND DIU GOVERNMENT OF GOA, DAMAN AND DIU Home Department (General! Directorate of Transport Public Notice I - Applications have been received for grant of stage carriage permits to operate buses on the following routes in response to the public notice of this office published in local newspapers. 'Wi.'.;' .. , t' -' S. No. Date of receIpt Name and address of the applicant M. V. No. Partaji to Agasaim via St. Oruz and back (~ buses). 10 6-12-77 Mis. Empresa Tl'ansportes Agasaim Panjim Limited, Registered Office GDR 3088 Pilar-Goa. 2. 6-12-77 Mis. Empresa Transportes Agasaim Panjim Limited, Pilar-Goa. New Bus 3. 6-12-77 Shri Minguel GraCias, P. O. Agasaim, Malwara, Tiswadi-Goa. GDS 1555 4. 8-12-77 Mis. Triveni Travels, Betim, Bardez, Goa. GDS 1511 5. 8-12-77 Shri Laximan Yeshwant Palyenkar, H. No. 112, Porvorim, Bardez-Goa. GDT 2482 6. 12-12-77 Shri Kashinath S. Natekar, Ansa Bhat, Mapu~, Bardez-Goa. GDT 2383 I, 7. 12-12-77 Mis. Empresa Transportes Agasaim Panjim Limited, Registered Office GDR 3090 I Pilar~Goa.- 8. 12-12-77 Shri Mukund Narayan ,Mayenkar, H. No. 260, Neura, Mandur-Goa. GDS 1596 I 9. 15-12-77 Shri VaSsudev Shankar Vadkar, Prabhavati Niwas, 'St. Inez, Panaji-Goa.. 'Bus Ashok Leyland 10. 16-12-77 Shri Roghuvir D. Hoble, Merces-Wadi Post Santa Cruz, nhas-Goa. Ashok Leyland I Bus New r vehicle 11. 16-12-77 8hri Gurudas Ramnath Nalk, Mapusa-Goa. -

Œ¼'윢'ݙȅA†[…G 2

(6) Evaluation of Sewerage Facilities 1) Sewer Network Results of hydraulic analysis (flow capacity) on sewer network of Panaji City to identify problems in existing condition, year 2001, are shown in this section. a. Study Methodology The steps of analysis are shown below. Step 1: Figure out sewer service area, population Step 2: Presume contributory population of target sewers of network Step 3: Presume design flow of each sewer Step 4: Figure out diameter, length, and slope of each sewer Step 5: Figure out flow velocity and flow capacity of each sewer (Manning’s formula) Step 6: Compare the flow capacity with the design flow and judge Assumptions as shown in Table 32.12 are set for the analysis on the sewer network for evaluation of sewer network capacity. Table 32.12 Assumptions for Sewer Network Analysis Item Assumption Population Adopt population mentioned in the Report for year 2001 Connection rate 100%, that is whole wastewater generated is discharged into sewers Contributory population of each sewer Distribute zone population to each sewer catchments proportional to its sewer length Sewer cross-section area reduction due to Not considered silting Flow capacity margin Not considered b. Sewerage Zone wise Population and Wastewater Quantity Sewerage zone wise population and generated wastewater quantity in year 2001 have been considered as shown in Table 32.6. c. Flow of Each Sewer As contributory area, population and flow of each sewer for year 2001 are not mentioned in the Report “Project Outline on Environmental Upgrading of Panaji City, Phase-1”, it was assumed 3 - 83 that population in the catchment area of each sewer is proportional to its sewer length. -

Goddemal Village Declared Containment Zone

GODDEMAL VILLAGE DECLARED CONTAINMENT ZONE: DEULWADA, KASARWADA BUFFER ZONES Panaji: June 13, 2020 The District Magistrate, North Goa has declared entire geographical area of Goddemal village as Containment Zones and the villages of Deulwada and Kasarwada as Buffer Zones in Sattari Taluka for all purpose and objectives prescribed in the protocol of COVID-19 to prevent its spread in the adjoining areas. An action plan is also prescribed to be carried out including screening, testing of suspected cases, quarantine, isolation, social distancing and other public health measures in the Containment Zone effectively for combating the situation at hand. The Rapid Response team headed by Dy. Collector & SDM, Sattari and consisting of other members which includes Dy. Superintendent of Police, Bicholim, Health Officer, Community Health Centre, Sanquelim, Bicholim, Mamletdar of Sattari, Station Fire officer and Inspector of Civil Supplies from Valpoi and EE PWD (Bldg) will investigate the outbreak and initiate control measure by assessing the situation. The Health Officer, Community Health Centre (CHC), Sanquelim will deploy sufficient number of teams comprising of Medical, ANM to conduct door to door thermal screening of each and every person of entire household falling in Containment Zone and will be supervised by a Doctor appointed by the Health Officer, Community Health Centre, Sanquelim. All the staff on duty will be provided with Personal Protective Equipment. Health Check-up of sick persons of the area will be carried out through mobile check-up vans. The list of persons found sick marked with red ink will be prepared for further necessary action. All positive cases will be shifted to Covid Care Centre or Covid hospital for further management as required. -

Official Gazette Government of Goa, Daman· and Diu

I BEGD. GOA-a I Panaji, 28th November, 1974 (Agrahayana 7,1896) SERIES III No. 35 r·_ OFFICIAL GAZETTE GOVERNMENT OF GOA, DAMAN· AND DIU GOVERNMENT OF GOA. DAMAN Tr8.:ttte restrictions in Sector No. 2 This Sector will conS1S1: of Ribandar Cross: upto Old' Goa AND DIU (excluding the Old Goa entry cross- upto Bus stand near the Church of.St. Jobn of Goa) Kadamba Road-Chlmbel-Rlbandar Road upto RlbandarCross. Home Department (Transport and Accommodation) a) The entire route in this sector Will be one way. The vehicles mice enter IDbandar, will proceed towards Old Goa Office of the District Magistrate except those vehicles in Ribandar. These vehicles in Ribandar will not be parked on thiS: road. The buses running betwean: Panaji- and Ri bandar will however be allowed to proceed Notification upto one way at S. Pedro and return by same road. _ b) No bus or any other- transport vehicle will be allowed No. JUD/MV/74/1261 to stop on this road. The buses plying between Pana:ji- and Under Seotion 74 of the Motor Vehicles Act. 1939 the Old Goa will not stop anywhere on th1s road. However buses for places beyond Old Goa w!U be allowed to stop for the following traffic ·regulations are notified on account of the time' required for passengers to get in and get out of bus. Exposition of St., Francis Xavier with immediate effect at the bus stops at Ribandar CrQss, Ajuda Chapel and until further orders. near G. M. C. HOSpital. Traffic restriottODS hi Sector I c) The Rlbandar bound buses will be allowed to stop at the abbve steps in Ribandar. -

Molecular Insight Into the Genesis of Ranked Caste Populations Of

This information has not been peer-reviewed. Responsibility for the findings rests solely with the author(s). comment Deposited research article Molecular insight into the genesis of ranked caste populations of western India based upon polymorphisms across non-recombinant and recombinant regions in genome Sonali Gaikwad1 and VK Kashyap1,2* reviews Addresses: 1National DNA Analysis Center, Central Forensic Science Laboratory, Kolkata -700014, India. 2National Institute of Biologicals, Noida-201307, India. Correspondence: VK Kasyap. E-mail: [email protected] reports Posted: 19 July 2005 Received: 18 July 2005 Genome Biology 2005, 6:P10 The electronic version of this article is the complete one and can be This is the first version of this article to be made available publicly and no found online at http://genomebiology.com/2005/6/8/P10 other version is available at present. © 2005 BioMed Central Ltd deposited research refereed research .deposited research AS A SERVICE TO THE RESEARCH COMMUNITY, GENOME BIOLOGY PROVIDES A 'PREPRINT' DEPOSITORY TO WHICH ANY ORIGINAL RESEARCH CAN BE SUBMITTED AND WHICH ALL INDIVIDUALS CAN ACCESS interactions FREE OF CHARGE. ANY ARTICLE CAN BE SUBMITTED BY AUTHORS, WHO HAVE SOLE RESPONSIBILITY FOR THE ARTICLE'S CONTENT. THE ONLY SCREENING IS TO ENSURE RELEVANCE OF THE PREPRINT TO GENOME BIOLOGY'S SCOPE AND TO AVOID ABUSIVE, LIBELLOUS OR INDECENT ARTICLES. ARTICLES IN THIS SECTION OF THE JOURNAL HAVE NOT BEEN PEER-REVIEWED. EACH PREPRINT HAS A PERMANENT URL, BY WHICH IT CAN BE CITED. RESEARCH SUBMITTED TO THE PREPRINT DEPOSITORY MAY BE SIMULTANEOUSLY OR SUBSEQUENTLY SUBMITTED TO information GENOME BIOLOGY OR ANY OTHER PUBLICATION FOR PEER REVIEW; THE ONLY REQUIREMENT IS AN EXPLICIT CITATION OF, AND LINK TO, THE PREPRINT IN ANY VERSION OF THE ARTICLE THAT IS EVENTUALLY PUBLISHED. -

Political Economy of a Dominant Caste

Draft Political Economy of a Dominant Caste Rajeshwari Deshpande and Suhas Palshikar* This paper is an attempt to investigate the multiple crises facing the Maratha community of Maharashtra. A dominant, intermediate peasantry caste that assumed control of the state’s political apparatus in the fifties, the Marathas ordinarily resided politically within the Congress fold and thus facilitated the continued domination of the Congress party within the state. However, Maratha politics has been in flux over the past two decades or so. At the formal level, this dominant community has somehow managed to retain power in the electoral arena (Palshikar- Birmal, 2003)—though it may be about to lose it. And yet, at the more intricate levels of political competition, the long surviving, complex patterns of Maratha dominance stand challenged in several ways. One, the challenge is of loss of Maratha hegemony and consequent loss of leadership of the non-Maratha backward communities, the OBCs. The other challenge pertains to the inability of different factions of Marathas to negotiate peace and ensure their combined domination through power sharing. And the third was the internal crisis of disconnect between political elite and the Maratha community which further contribute to the loss of hegemony. Various consequences emerged from these crises. One was simply the dispersal of the Maratha elite across different parties. The other was the increased competitiveness of politics in the state and the decline of not only the Congress system, but of the Congress party in Maharashtra. The third was a growing chasm within the community between the neo-rich and the newly impoverished. -

Vijaydurg ( Location on Map )

Vijaydurga The sleepy village boasts of a seemingly impregnable, pre Shivaji period fort that, maritime history says, was the scene of many a bloody battle. It has been attacked from the sea by the British to take it over from its Indian occupants. A dilapidated board at the entrance of the fort tells you its history. Some of the board is readable whilst the rest is guesswork since the paint has peeled off. Once upon a time the steamer from Bombay to Goa used to halt at the jetty near the entrance to the fort. Now the catamaran whizzes past oblivious of the fort, the town and the beach. Incidentally the one of the best views of the fort is from this jetty. The fort stretches out in to the sea and a walk inside its precincts is worthwhile. When I was there last, the organisers of the McDowell Bombay – Goa Regatta had established a staging post inside the fort and there was quite a bit of revelry. Otherwise no one really bothers to come here. The locals inform us that Mr Vijay Mallya, the liquor baron, boss of United Breweries that owns the McDowell Brand, has bought over a 100 acres of land in the area just north of here with a view to building a resort some time in the future. Gives you an indication of the potential of the place. Vijaydurg’s beach is quite hidden from view and is not obvious to the casual visitor. Ask for the small bus terminus just before you get to the fort and the road ends. -

North Goa Name of the Name of the Panchayat/ Sr

Tika Utsav 3 - North Goa Name of the Name of the Panchayat/ Sr. No. Venue Date CHC/PHC Municipality 1 CHC Pernem Mandrem ZP Hall, Mandrem 13, 14 june Morjim Sarvajanik Ganapati Hall, Morjim 15, 16 June Harmal Sarvajanik Ganeshotsav Hall, Harmal 17, 18 June Palye GPC Madhlawada, Palye 19, 20 June Keri Panchayat Hall 21, 22 June Parse Panchayat hall, Parse 23, 24, June Agarwada-Chopde Panchayat Hall 25, 26 June Virnoda Panchayat Hall 27, 28, June Korgao Panchayat Hall, Korgao 29, 30 June 2 PHC Casarvanem Varkhand Panchayat Hall, Varkhand 13, 14 june Torse Panchayat Hall 15, 16 June Chandel-Hansapur Panchayat Hall 17, 18 June Ugave Panchayat Hall 19, 20 June Ozari Panchayat Hall 21, 22 June Dhargal Panchayat Hall 23, 24, June Ibrampur Panchayat Hall 25, 26 June Halarn Panchayat Hall 27, 28, June Poroscode Panchayat Hall 29, 30 June 3 CHC Bicholim Latambarce Govt Primary School, Ladfe 13, 14, June Latambarce Govt. Primary School, Nanoda 15th June Van-Maulinguem Govt. Primary School, Maulinguem 16th Jun Menkure Govt. High School, Menkure 17, 18 June Mulgao Govt. Primary School, Shirodwadi 19, 20 Junw Advalpal Govt Primary Middle School, Gaonkarwada 21st Jun Latambarce - Usap / Bhatwadi GPS Usap 23 rd June Latambarce - Dodamarg & Kharpal GPS Dodamarg 25, 26 June Latambarce - Kasarpal & Vadaval GPS Kasarpal 27, 28 June Sal Panchayat Hall, Sal 29-Jun Sal - Kholpewadi/ Punarvasan / Shivajiraje High School, Kholpewadi 30-Jun Sirigao at Mayem Primary Health Centre, Kelbaiwada- Mayem 24th June Tika Utsav 3 - North Goa Name of the Name of the Panchayat/ -

North Goa District Factbook |

Goa District Factbook™ North Goa District (Key Socio-economic Data of North Goa District, Goa) January, 2018 Editor & Director Dr. R.K. Thukral Research Editor Dr. Shafeeq Rahman Compiled, Researched and Published by Datanet India Pvt. Ltd. D-100, 1st Floor, Okhla Industrial Area, Phase-I, New Delhi-110020. Ph.: 91-11-43580781, 26810964-65-66 Email : [email protected] Website : www.districtsofindia.com Online Book Store : www.datanetindia-ebooks.com Also available at : Report No.: DFB/GA-585-0118 ISBN : 978-93-86683-80-9 First Edition : January, 2017 Second Edition : January, 2018 Price : Rs. 7500/- US$ 200 © 2018 Datanet India Pvt. Ltd. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, mechanical photocopying, photographing, scanning, recording or otherwise without the prior written permission of the publisher. Please refer to Disclaimer & Terms of Use at page no. 208 for the use of this publication. Printed in India North Goa District at a Glance District came into Existence 30th May, 1987 District Headquarter Panaji Distance from State Capital NA Geographical Area (In Square km.) 1,736 (Ranks 1st in State and 522nd in India) Wastelands Area (In Square km.) 266 (2008-2009) Total Number of Households 1,79,085 Population 8,18,008 (Persons), 4,16,677 (Males), 4,01,331 (Females) (Ranks 1st in State and 480th in India) Population Growth Rate (2001- 7.84 (Persons), 7.25 (Males), 8.45 (Females) 2011) Number of Sub Sub-districts (06), Towns (47) and Villages (194) Districts/Towns/Villages Forest Cover (2015) 53.23% of Total Geographical Area Percentage of Urban/Rural 60.28 (Urban), 39.72 (Rural) Population Administrative Language Konkani Principal Languages (2001) Konkani (50.94%), Marathi (31.93%), Hindi (4.57%), Kannada (4.37%), Urdu (3.44%), Malayalam (1.00%) and Others (0.17%) Population Density 471 (Persons per Sq. -

Designated Officials Information Sr

DIRECTORATE OF SKILL DEVELOPMENT & ENTREPRENEURSHIP DESIGNATED OFFICIALS INFORMATION SR. CONTACT ITI NAME NAME OF THE OFFICIAL DESIGNATION EMAIL OF ITI NO. NUMBER In case of any issues in filling of Online Application form Kindly Call 9225905914 / Email: [email protected] or Contact any of the following ITIs: NORTH GOA Pernem Govt.ITI 1 PERNEM GOVT. ITI SHRI. DATTAPRASAD V. PALNI PRINCIPAL 9923144341 [email protected] 2 PERNEM GOVT. ITI SHRI. AUDUMBER SALGAONKAR V.I. /SHIFT INCHARGE 9923530751 [email protected] Mapusa Govt.ITI 1 Mapusa Govt. ITI Vilas Shetgaonkar Vocational Instructor 0832-2959999 [email protected] 2 Mapusa Govt. ITI Pushparaj Mandrekar Vocational Instructor 0832-2959999 [email protected] Bicholim Govt.ITI 1 Bicholim Govt. ITI Shri Chandrakant Gawas Shetkar Programming Assistant 9764237045 [email protected] 2 Bicholim Govt. ITI Shri Bibin Abraham V. I. (Solar Technician) 9049076089 [email protected] Sattari Govt.ITI 1 Sattari Govt. ITI Shri Nilesh P. Gawas Principal 9637084864 [email protected] 2 Sattari Govt. ITI Shri Narayan Salgaonkar Vocational Instructor 8390719602 [email protected] 3 Sattari Govt. ITI Shri A. G. Manju Group Instructor 7666493962 [email protected] 4 Sattari Govt. ITI Shri Sagar Gawas Programming Assistant 9923245442 [email protected] Panaji Govt.ITI 1 Panaji Govt ITI Vasudev P. Phadte Surveyor 7875692109 [email protected] 2 Panaji Govt ITI Sudesh Majji V.I (COPA) 8788415089 [email protected] 3 Panaji Govt ITI Aditya Raikar V.I (COPA) 9764222244 [email protected] 4 Panaji Govt ITI Americo Rodrigues V.I 7776084962 [email protected] SOUTH GOA Cacora Govt.ITI 1 Cacora Govt.