I.," American String Quartet

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

5 Music Cruises 2019 E.Pub

“The music is not in the notes, but in the silence between.” Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart RHINE 2019 DUDOK QUARTET Aer compleng their studies with disncon at the Dutch String Quartet Academy in 20 3, the Quartet started to have success at internaonal compeons and to be recognized as one of the most promising young European string quartets of the year. In 20 4, they were awarded the Kersjes ,rize for their e-ceponal talent in the Dutch chamber music scene. .he Quartet was also laureate and winner of two special prizes during the 7th Internaonal String Quartet 0ompeon 20 3 1 2ordeau- and won st place at both the st Internaonal String Quartet 0ompeon 20 in 3adom 4,oland5 and the 27th 0harles 6ennen Internaonal 0hamber Music 0ompe7 on 20 2. In 20 2, they received 2nd place at the 8th 9oseph 9oachim Internaonal 0hamber Music 0ompeon in Weimar 4:ermany5. .he members of the quartet ;rst met in the Dutch street sym7 phony orchestra “3iccio=”. From 2009 unl 20 , they stu7 died with the Alban 2erg Quartet at the School of Music in 0ologne, then to study with Marc Danel at the Dutch String Quartet Academy. During the same period, the quartet was coached intensively by Eberhard Feltz, ,eter 0ropper 4Aindsay Quartet5, Auc7Marie Aguera 4Quatuor BsaCe5 and Stefan Metz. Many well7Dnown contemporary classical composers such as Kaija Saariaho, MarD7Anthony .urnage, 0alliope .sou7 paDi and Ma- Knigge also worDed with the quartet. In 20 4, the Quartet signed on for several recordings with 3esonus 0lassics, the worldEs ;rst solely digital classical music label. -

A Chronology of All Artists' Appearances with the Chamber

75 Years of Chamber Music Excellence: A Chronology of all artists’ appearances with the Chamber Music Society of Louisville st 1 Season, 1938 – 1939 Kathleen Parlow, violin and Gunnar Johansen, piano The Gordon String Quartet The Coolidge Quartet The Heermann Trio nd 2 Season, 1939 – 1940 The Budapest String Quartet The Stradivarius Quartet Marcel Hubert, cello and Harold Dart, piano rd 3 Season, 1940 – 1941 Ralph Kirkpatrick, harpsichord and Lois Wann, oboe Belgian PianoString Quartet The Coolidge Quartet th 4 Season, 1941 – 1942 The Trio of New York The Musical Art Quartet The Pro Arte Quartet th 5 Season, 1942 – 1943 The Budapest String Quartet The Coolidge Quartet The Stradivarius Quartet th 6 Season, 1943 – 1944 The Budapest String Quartet Gunnar Johansen, piano and Antonio Brosa, violin The Musical Art Quartet th 7 Season, 1944 – 1945 The Budapest String Quartet The Pro Arte Quartet Alexander Schneider, violin and Ralph Kirkpatrick, harpsichord th 8 Season, 1945 – 1946 The Musical Art Quartet Nikolai Graudan, cello and Joanna Graudan, piano Philip Manuel, harpsichord and Gavin Williamson, harpsichord The Budpest String Quartet th 9 Season, 1946 – 1947 The Louisville Philharmonic String Quartet with Doris Davis, piano The Albeneri Trio The Budapest String Quartet th 10 Season, 1947 – 1948 Alexander Schneider, violin and Ralph Kirkpatrick, harpsichord The Budapest String Quartet The London String Quartet The Walden String Quartet The Albeneri Trio th 11 Season, 1948 – 1949 The Alma Trio -

Cds by Composer/Performer

CPCC MUSIC LIBRARY COMPACT DISCS Updated May 2007 Abercrombie, John (Furs on Ice and 9 other selections) guitar, bass, & synthesizer 1033 Academy for Ancient Music Berlin Works of Telemann, Blavet Geminiani 1226 Adams, John Short Ride, Chairman Dances, Harmonium (Andriessen) 876, 876A Adventures of Baron Munchausen (music composed and conducted by Michael Kamen) 1244 Adderley, Cannonball Somethin’ Else (Autumn Leaves; Love For Sale; Somethin’ Else; One for Daddy-O; Dancing in the Dark; Alison’s Uncle 1538 Aebersold, Jamey: Favorite Standards (vol 22) 1279 pt. 1 Aebersold, Jamey: Favorite Standards (vol 22) 1279 pt. 2 Aebersold, Jamey: Gettin’ It Together (vol 21) 1272 pt. 1 Aebersold, Jamey: Gettin’ It Together (vol 21) 1272 pt. 2 Aebersold, Jamey: Jazz Improvisation (vol 1) 1270 Aebersold, Jamey: Major and Minor (vol 24) 1281 pt. 1 Aebersold, Jamey: Major and Minor (vol 24) 1281 pt. 2 Aebersold, Jamey: One Dozen Standards (vol 23) 1280 pt. 1 Aebersold, Jamey: One Dozen Standards (vol 23) 1280 pt. 2 Aebersold, Jamey: The II-V7-1 Progression (vol 3) 1271 Aerosmith Get a Grip 1402 Airs d’Operettes Misc. arias (Barbara Hendricks; Philharmonia Orch./Foster) 928 Airwaves: Heritage of America Band, U.S. Air Force/Captain Larry H. Lang, cond. 1698 Albeniz, Echoes of Spain: Suite Espanola, Op.47 and misc. pieces (John Williams, guitar) 962 Albinoni, Tomaso (also Pachelbel, Vivaldi, Bach, Purcell) 1212 Albinoni, Tomaso Adagio in G Minor (also Pachelbel: Canon; Zipoli: Elevazione for Cello, Oboe; Gluck: Dance of the Furies, Dance of the Blessed Spirits, Interlude; Boyce: Symphony No. 4 in F Major; Purcell: The Indian Queen- Trumpet Overture)(Consort of London; R,Clark) 1569 Albinoni, Tomaso Concerto Pour 2 Trompettes in C; Concerto in C (Lionel Andre, trumpet) (also works by Tartini; Vivaldi; Maurice André, trumpet) 1520 Alderete, Ignacio: Harpe indienne et orgue 1019 Aloft: Heritage of America Band (United States Air Force/Captain Larry H. -

Everything Essential

Everythi ng Essen tial HOW A SMALL CONSERVATORY BECAME AN INCUBATOR FOR GREAT AMERICAN QUARTET PLAYERS BY MATTHEW BARKER 10 OVer tONeS Fall 2014 “There’s something about the quartet form. albert einstein once Felix Galimir “had the best said, ‘everything should be as simple as possible, but not simpler.’ that’s the essence of the string quartet,” says arnold Steinhardt, longtime first violinist of the Guarneri Quartet. ears I’ve been around and “It has everything that is essential for great music.” the best way to get students From Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven, and Schubert through the romantics, the Second Viennese School, Debussy, ravel, Bartók, the avant-garde, and up to the present, the leading so immersed in the act of composers of each generation reserved their most intimate expression and genius for that basic ensemble of two violins, a viola, and a cello. music making,” says Steven Over the past century america’s great music schools have placed an increasing emphasis tenenbom. “He was old on the highly specialized and rigorous discipline of quartet playing. among them, Curtis holds a special place despite its small size. In the last several decades alone, among the world and new world.” majority of important touring quartets in america at least one chair—and in some cases four—has been filled by a Curtis-trained musician. (Mr. Steinhardt, also a longtime member of the Curtis faculty, is one.) looking back, the current golden age of string quartets can be traced to a mission statement issued almost 90 years ago by early Curtis director Josef Hofmann: “to hand down through contemporary masters the great traditions of the past; to teach students to build on this heritage for the future.” Mary louise Curtis Bok created a haven for both teachers and students to immerse themselves in music at the highest levels without financial burden. -

A Tribute to Hans-Karl Piltz Marina Thibeault Viola with David Gillham Violin Eric Wilson Cello Jasper Wood Violin

Wednesday Noon Hours UBC SCHOOL OF MUSIC A Tribute to Hans-Karl Piltz Marina Thibeault viola with David Gillham violin Eric Wilson cello Jasper Wood violin Duo in B-flat major for violin and viola, K. 424 W.A. Mozart i. Adagio-Allegro (1756-1791) ii. Andante cantabile iii. Tema con variazioni David Gillham violin Marina Thibeault viola Lullaby and Grotesque for viola and cello Rebecca Clarke i. Lullaby (1886-1979) ii. Grotesque Marina Thibeault viola Eric Wilson cello Three Madrigals Bohuslav Martinů i. Poco allegro - Poco vivo (1890-1959) ii. Poco andante - Andante moderato iii. Allegro - Moderato Jasper Wood violin Marina Thibeault viola Composed: Mozart (1783); Clarke (1916); Martinů (1947) # We acknowledge that the University of British Columbia is situated on the traditional, ancestral, and unceded territory of the Musqueam people. Hans-Karl Piltz (1923–2020) Professor Hans-Karl Piltz was a talented violist and teacher who helped shape the School of Music as it evolved from a small Bachelor of Arts program in the late 1950s to the large and thriving School it is today. He was 96 years old when he passed away this April. Prof. Piltz loved teaching, and in 1959 joined the UBC Department of Music — as the School of Music was then known. As Professor of Viola, he mentored several generations of strings musicians who have gone on to long and successful careers in orchestras and as soloists in North America, Europe, and all over the world. He founded and directed the UBC Symphony Orchestra from 1959–1970 and also helped found the Vancouver Society for Early Music — now known as Early Music Vancouver — in 1969. -

Schubert's Flights of Fantasie

Kristian Chong & Friends Schubert’s Flights of Fantasie LOCAL Monday, 2 May 2016 6pm, Salon HEROES Presented by Melbourne Recital Centre and Kristian Chong & Friends ARTISTS Sophie Rowell, violin Kristian Chong, piano PROGRAM WOLFGANG AMADEUS MOZART Sonata for Piano and Violin in B-flat, K.454 I Largo - Allegro II Andante III Rondo: Allegretto ANDREW SCHULTZ Night Flight (2003) FRANZ SCHUBERT Fantasie for Piano and Violin in C, D.934 Andante molto–Allegretto–Andantino–Tempo I–Allegro vivace–Allegretto–Presto ABOUT THE MUSIC As was customary at the time, Mozart termed his early examples “sonatas for piano with violin ad libitum” but not the later Sonata K454, which he characterised as a “sonata for piano with violin accompaniment”. Yet this is a true chamber partnership, with K454 demanding a violinist of consummate skill. The opening commences with a stately Largo; it quickly retreats into a tender statement before launching into a swift Allegro with many conversational imitations and parallel lines. An Andante follows in which Mozart achieves a masterly blend of cantabile and beauty. A minor episode darkens the mood while maintaining enchanting lyricism. The concluding movement opens with a statement first spoken by the violin, with intervening episodes sandwiched between reprises of the theme giving opportunities to express Mozart’s penchant for unexpected and delectable melodic twists and turns. Night Flight was originally written as the fourth movement from a sextet called Mephisto in 1990. Ukranian violinist Dmitri Tkachenko commissioned this transcription and debuted it with Kristian Chong in London in 2003. The piece is a danse macabre for the modern age. -

View PDF Online

MARLBORO MUSIC 60th AnniversAry reflections on MA rlboro Music 85316_Watkins.indd 1 6/24/11 12:45 PM 60th ANNIVERSARY 2011 MARLBORO MUSIC Richard Goode & Mitsuko Uchida, Artistic Directors 85316_Watkins.indd 2 6/23/11 10:24 AM 60th AnniversA ry 2011 MARLBORO MUSIC richard Goode & Mitsuko uchida, Artistic Directors 85316_Watkins.indd 3 6/23/11 9:48 AM On a VermOnt HilltOp, a Dream is BOrn Audience outside Dining Hall, 1950s. It was his dream to create a summer musical community where artists—the established and the aspiring— could come together, away from the pressures of their normal professional lives, to exchange ideas, explore iolinist Adolf Busch, who had a thriving music together, and share meals and life experiences as career in Europe as a soloist and chamber music a large musical family. Busch died the following year, Vartist, was one of the few non-Jewish musicians but Serkin, who served as Artistic Director and guiding who spoke out against Hitler. He had left his native spirit until his death in 1991, realized that dream and Germany for Switzerland in 1927, and later, with the created the standards, structure, and environment that outbreak of World War II, moved to the United States. remain his legacy. He eventually settled in Vermont where, together with his son-in-law Rudolf Serkin, his brother Herman Marlboro continues to thrive under the leadership Busch, and the great French flutist Marcel Moyse— of Mitsuko Uchida and Richard Goode, Co-Artistic and Moyse’s son Louis, and daughter-in-law Blanche— Directors for the last 12 years, remaining true to Busch founded the Marlboro Music School & Festival its core ideals while incorporating their fresh ideas in 1951. -

Whlive0012 Booklet 14/8/06 12:12 Pm Page 2

WHLive0012 booklet 14/8/06 12:12 pm Page 2 WHLive0012 Also Available Made & Printed in England NASH ENSEMBLE Beethoven Clarinet Trio in Bb Mendelssohn Octet SIR THOMAS ALLEN baritone WHLive0001 MALCOLM MARTINEAU piano Songs by Beethoven, Wolf, Butterworth Vaughan Williams and Bridge 0002 ARDITTI QUARTET WHLive Nancarrow String Quartet No. 3 Ligeti String Quartet No. 2 DAME FELICITY LOTT soprano Dutilleux String Quartet ‘Ainsi la nuit’ GRAHAM JOHNSON piano 0003 WHLive Fallen Women and Virtuous Wives Songs by Haydn, Strauss, Brahms and Wolf WHLive0004 ACADEMY OF ANCIENT MUSIC Concerti and Concerti Grossi by Handel, JS Bach and Vivaldi PETER SCHREIER tenor WHLive0005 ANDRÁS SCHIFF piano Schubert Songs WHLive0006 NASH ENSEMBLE Schumann Märchenerzählungen Moscheles Fantasy, Variations & Finale DAME MARGARET PRICE soprano Brahms Clarinet Quintet in B minor GEOFFREY PARSONS piano WHLive0007 Songs by Schubert, Mahler and R Strauss JOYCE DIDONATO mezzo-soprano WHLive0008 JULIUS DRAKE piano Songs by Fauré, Hahn and Head KOPELMAN QUARTET Arias by Rossini and Handel Schubert String Quartet in D minor 0009 WHLive ‘Death and the Maiden’ Tchaikovsky String Quartet in Eb minor WHLive0010 SOILE ISOKOSKI soprano MARITA VIITASALO piano Songs by Sibelius, Strauss and Berg WHLive0011 Available from all good record shops and from www.wigmore-hall.org.uk/live WHLive0012 booklet 14/8/06 12:12 pm Page 3 Ysaÿe Quartet Debussy String Quartet in G minor Stravinsky Concertino Three Pieces for String Quartet Double Canon Fauré String Quartet in E minor WHLive0012 booklet 14/8/06 12:12 pm Page 4 Ysaÿe Quartet CLAUDE DEBUSSY String Quartet in G minor Op. 10 (1893) 01 Animé et très décidé 07.04 02 Assez vif et bien rythmé 03.50 03 Andantino, doucement expressif 08.17 04 Très modéré – Très mouvementé avec passion 07.24 IGOR STRAVINSKY 05 Concertino (1920) 07.00 Three Pieces for String Quartet (1914) 06 ‘Dance’ 00.49 07 ‘Eccentric’ 01.51 08 ‘Canticle’ 04.46 09 Double Canon (1959) 02.16 GABRIEL FAURÉ String Quartet in E minor Op. -

Digital Booklet Porgy & Bess

71 TRACKS THE AMADEUS QUARtet ReCORDINGS VOL. I BEETHOVEN Berlin, 1950-1967 recording producer: Wolfgang Gottschalk (Op. 127) Hartung (Op. 59, 2) Hermann Reuschel (Op. 18, 2-5 / Op. 59, 1 / Op. 130-133 / Op. 135 / Op. 29) Salomon (Op. 18, 1+6 / Op. 59, 3 / Op. 95) recording engineer: Siegbert Bienert (Op. 18, 5 / Op. 130-133 / Op. 29) Peter Burkowitz (Op. 18, 6) THE Heinz Opitz (Op. 18, 2 / Op. 59, 1+2 / Op. 127 / Op. 135) Preuss (Op. 18, 1 / Op. 59, 3 / Op. 95) Alfred Steinke (Op. 18, 3+4) AMADEUS QUARtet ReCORDinGS Berlin, 1950-1967 Eine Aufnahme von RIAS Berlin (lizenziert durch Deutschlandradio) recording: P 1950 - 1967 Deutschlandradio research: Rüdiger Albrecht remastering: P 2013 Ludger Böckenhoff rights: audite claims all rights arising from copyright law and competition law in relation to research, compilation and re-mastering of the original audio tapes, VOL. I BEETHOVEN as well as the publication of this CD. Violations will be prosecuted. The historical publications at audite are based, without exception, on the original tapes from broadcasting archives. In general these are the original analogue tapes, MstASTER RELEASE which attain an astonishingly high quality, even measured by today’s standards, with their tape speed of up to 76 cm/sec. The remastering – professionally com- petent and sensitively applied – also uncovers previously hidden details of the interpretations. Thus, a sound of superior quality results. CD publications based 1 on private recordings from broadcasts cannot be compared with these. AMADEUS-QUARtett further reading: Daniel Snowman: The Amadeus Quartet. The Men and the Music, violin I Norbert Brainin Robson Books (London, 1981) violin II Siegmund Nissel Gerd Indorf: Beethovens Streichquartette, Rombach Verlag (Freiburg i. -

American String Quartet

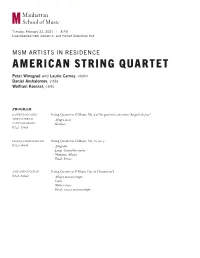

Tuesday, February 23, 2021 | 8 PM Livestreamed from Gordon K. and Harriet Greenfield Hall MSM ARTISTS IN RESIDENCE AMERICAN STRING QUARTET Peter Winograd and Laurie Carney, violin Daniel Avshalomov, viola Wolfram Koessel, cello PROGRAM JOSEPH BOLOGNE, String Quartet in G Major, No. 5 of Six quartetto concertans “Au goût du jour” CHEVALIER DE Allegro assai SAINT-GEORGES Gratioso (1745–1799) FRANZ JOSEPH HAYDN String Quartet in D Major, Op. 76, no. 5 (1732–1809) Allegretto Largo. Cantabile e mesto Menuetto. Allegro Finale. Presto ANTONÍN DVOŘÁK String Quartet in F Major, Op. 96 (“American”) (1841–1904) Allegro ma non troppo Lento Molto vivace Finale: vivace ma non troppo ABOUT THE ARTISTS American String Quartet Internationally recognized as one of the world’s foremost quartets, the American String Quartet marks its 46th season in 2020– 21. Critics and colleagues hold the Quartet in high esteem and many of today’s leading artists and composers seek out the Quartet for collaborations. The Quartet is also known for its performances of the complete quartets of Beethoven, Schubert, Schoenberg, Bartók, and Mozart. The Quartet’s recordings of the complete Mozart string quartets on a matched set of Stradivarius instruments are widely held to set the standard for this repertoire. To celebrate its 35th anniversary, the Quartet recorded an ambitious CD, Schubert’s Echo, released by NSS Music. The program invites the listener to appreciate the influence of Schubert on two masterworks of early 20th-century Vienna. In addition to quartets by European masters, the American naturally performs quartets by American composers. Their newest release, American Romantics (Apple Music, 2018), is a recording of Robert Sirota’s American Pilgrimage, Dvořák’s “American” quartet, and Barber’s Adagio for Strings.The American also champions contemporary music. -

For Immediate Release

For Immediate Release THE GUARNERI STRING QUARTET WILL CELEBRATE ITS 40TH ANNIVERSARY BY GIVING A GIFT TO THE PEOPLE OF NEW YORK CITY – A SERIES OF EVENTS AT LINCOLN CENTER, MONDAY AND TUESDAY, APRIL 11 AND 12, FREE AND OPEN TO THE PUBLIC PANEL DISCUSSION, MASTER CLASS AND OPEN REHEARSAL WILL CONTINUE THE GUARNERI’S 40TH ANNIVERSARY CELEBRATIONS The world-renowned Guarneri String Quartet, one of the most esteemed and beloved ensembles of our time, will continue its 40th anniversary celebration by giving a gift to the people of New York City: a series of three events on Monday and Tuesday, April 11 and 12, in the Daniel and Joanna S. Rose Rehearsal Studio of Lincoln Center, which will be free and open to the public. The events include a master class involving top young string quartets from The Juilliard School, the Curtis Institute of Music, and the Manhattan School of Music; an open rehearsal for the Guarneri String Quartet’s Alice Tully Hall concert on April 13 presented by The Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center; and a panel discussion with the members of the Guarneri Quartet, veteran members of historic string quartets, and members of the newest quartet generation. All three events will be held in the Rose Studio of the Rose Building (165 West 65th Street, 10th Floor; 65th Street and Amsterdam Avenue) and are free and open to the public on a first-come, first-served basis. Members of the Guarneri String Quartet are Arnold Steinhardt and John Dalley, violins; Michael Tree, viola; and Peter Wiley, cello. -

Catalogo Per Autori Ed Esecutori

Abel, Carl Friedrich Quartetti, archi, Op. 8, No. 5, la maggiore The Salomon Quartet The Schein String Quartet Addy, Obo Wawshishijay Kronos Quartet Adorno, Theodor Wiesengrund Zwei Stucke fur Strechquartett op. 2 Buchberger Quartett Albert, Eugene : de Quartetti, archi, Op. 7, la minore Sarastro Quartett Quartetti, archi, Op. 11, mi bemolle maggiore Sarastro Quartett Alvarez, Javier Metro Chabacano Cuarteto Latinoamericano 1 Alwyn, William Quartetti, archi, n. 3 Quartet of London Rhapsody for String Quartet Arditti string quartet Andersson, Per Polska fran Hammarsvall, Delsbo The Follinger-Hedberg Quartet The Galli Quintet The Goteborg Quartet The Halsingborg Quartet The Kjellstrom Quartet The Skane Quartet Andriessen, Hendrik Il pensiero Raphael Quartet Aperghis, Georges Triangle Carre Trio Le Cercle Apostel, Hans Erich Quartetti, archi, Op. 7 LaSalle Quartet Arenskij, Anton Stepanovic Quartetti, archi, op. 35 Paul Rosenthal, Vl Matthias Maurer, Vla Godfried Hoogeveen, Vlc Nathaniel Rosen, Vlc Arriaga y Balzola, Juan Crisostomo Jacobo Antonio : de Quartetti, archi, No. 1, re minore Voces Streichquartette Quartet sine nomine Rasoumovsky Quartet Quartetti, archi, No. 2, la maggiore Voces Streichquartette Quartet sine nomine Rasoumovsky Quartet 2 Quartetti, archi, Nr. 3, mi bemolle maggiore Voces Streichquartette Quartet sine nomine Rasoumovsky Quartet Atterberg, Kurt Quartetti, archi, Op. 11 The Garaguly Quartet Aulin, Tor Vaggvisa The Follinger-Hedberg Quartet The Galli Quintet The Goteborg Quartet The Halsingborg Quartet The Kjellstrom