Whlive0012 Booklet 14/8/06 12:12 Pm Page 2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

5 Music Cruises 2019 E.Pub

“The music is not in the notes, but in the silence between.” Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart RHINE 2019 DUDOK QUARTET Aer compleng their studies with disncon at the Dutch String Quartet Academy in 20 3, the Quartet started to have success at internaonal compeons and to be recognized as one of the most promising young European string quartets of the year. In 20 4, they were awarded the Kersjes ,rize for their e-ceponal talent in the Dutch chamber music scene. .he Quartet was also laureate and winner of two special prizes during the 7th Internaonal String Quartet 0ompeon 20 3 1 2ordeau- and won st place at both the st Internaonal String Quartet 0ompeon 20 in 3adom 4,oland5 and the 27th 0harles 6ennen Internaonal 0hamber Music 0ompe7 on 20 2. In 20 2, they received 2nd place at the 8th 9oseph 9oachim Internaonal 0hamber Music 0ompeon in Weimar 4:ermany5. .he members of the quartet ;rst met in the Dutch street sym7 phony orchestra “3iccio=”. From 2009 unl 20 , they stu7 died with the Alban 2erg Quartet at the School of Music in 0ologne, then to study with Marc Danel at the Dutch String Quartet Academy. During the same period, the quartet was coached intensively by Eberhard Feltz, ,eter 0ropper 4Aindsay Quartet5, Auc7Marie Aguera 4Quatuor BsaCe5 and Stefan Metz. Many well7Dnown contemporary classical composers such as Kaija Saariaho, MarD7Anthony .urnage, 0alliope .sou7 paDi and Ma- Knigge also worDed with the quartet. In 20 4, the Quartet signed on for several recordings with 3esonus 0lassics, the worldEs ;rst solely digital classical music label. -

A Chronology of All Artists' Appearances with the Chamber

75 Years of Chamber Music Excellence: A Chronology of all artists’ appearances with the Chamber Music Society of Louisville st 1 Season, 1938 – 1939 Kathleen Parlow, violin and Gunnar Johansen, piano The Gordon String Quartet The Coolidge Quartet The Heermann Trio nd 2 Season, 1939 – 1940 The Budapest String Quartet The Stradivarius Quartet Marcel Hubert, cello and Harold Dart, piano rd 3 Season, 1940 – 1941 Ralph Kirkpatrick, harpsichord and Lois Wann, oboe Belgian PianoString Quartet The Coolidge Quartet th 4 Season, 1941 – 1942 The Trio of New York The Musical Art Quartet The Pro Arte Quartet th 5 Season, 1942 – 1943 The Budapest String Quartet The Coolidge Quartet The Stradivarius Quartet th 6 Season, 1943 – 1944 The Budapest String Quartet Gunnar Johansen, piano and Antonio Brosa, violin The Musical Art Quartet th 7 Season, 1944 – 1945 The Budapest String Quartet The Pro Arte Quartet Alexander Schneider, violin and Ralph Kirkpatrick, harpsichord th 8 Season, 1945 – 1946 The Musical Art Quartet Nikolai Graudan, cello and Joanna Graudan, piano Philip Manuel, harpsichord and Gavin Williamson, harpsichord The Budpest String Quartet th 9 Season, 1946 – 1947 The Louisville Philharmonic String Quartet with Doris Davis, piano The Albeneri Trio The Budapest String Quartet th 10 Season, 1947 – 1948 Alexander Schneider, violin and Ralph Kirkpatrick, harpsichord The Budapest String Quartet The London String Quartet The Walden String Quartet The Albeneri Trio th 11 Season, 1948 – 1949 The Alma Trio -

Schubert's Flights of Fantasie

Kristian Chong & Friends Schubert’s Flights of Fantasie LOCAL Monday, 2 May 2016 6pm, Salon HEROES Presented by Melbourne Recital Centre and Kristian Chong & Friends ARTISTS Sophie Rowell, violin Kristian Chong, piano PROGRAM WOLFGANG AMADEUS MOZART Sonata for Piano and Violin in B-flat, K.454 I Largo - Allegro II Andante III Rondo: Allegretto ANDREW SCHULTZ Night Flight (2003) FRANZ SCHUBERT Fantasie for Piano and Violin in C, D.934 Andante molto–Allegretto–Andantino–Tempo I–Allegro vivace–Allegretto–Presto ABOUT THE MUSIC As was customary at the time, Mozart termed his early examples “sonatas for piano with violin ad libitum” but not the later Sonata K454, which he characterised as a “sonata for piano with violin accompaniment”. Yet this is a true chamber partnership, with K454 demanding a violinist of consummate skill. The opening commences with a stately Largo; it quickly retreats into a tender statement before launching into a swift Allegro with many conversational imitations and parallel lines. An Andante follows in which Mozart achieves a masterly blend of cantabile and beauty. A minor episode darkens the mood while maintaining enchanting lyricism. The concluding movement opens with a statement first spoken by the violin, with intervening episodes sandwiched between reprises of the theme giving opportunities to express Mozart’s penchant for unexpected and delectable melodic twists and turns. Night Flight was originally written as the fourth movement from a sextet called Mephisto in 1990. Ukranian violinist Dmitri Tkachenko commissioned this transcription and debuted it with Kristian Chong in London in 2003. The piece is a danse macabre for the modern age. -

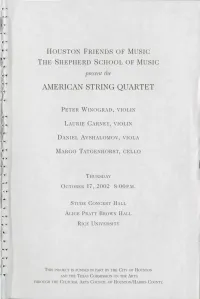

I.," American String Quartet

HOUSTON FRIENDS OF MUSIC THE SHEPHERD SCHOOL OF MUSIC present the AMERICAN STRING QUARTET PETER WINOGRAD, VIOLIN LAURIE CARNEY, VIOLIN DANIEL AVSHALOMOV, VIOLA MARGO TATGENHORST, CELLO THURSDAY OCTOBER 17, 2002 8:00P.M. STUDE CONCERT HALL ALICE PRATT BROWN HALL RICE UNIVERSITY I.," THIS PROJECT IS FUNDED IN PART BY TIIE CITY OF HOUSTON ~: AND THE TEXAS COMMISSION ON TIIE ARTS THROUGH TIIE CULTURAL ARTS COUNCIL OF IIOUSTON/lL-\RRJS COUNTY. AMERICAN STRING QUARTET -PROGRAM- WOLFGANG AMADEUS MOZART (1756-1791) • Quartet in E-flat Major, K. 42 8 Allegro non troppo Andante con moto Menuetto: Allegro Allegro vivace DMITRI SHOSTAKOVICH (1906-1975) Quartet No. 3 in F Major, Op. 73 (1946) Allegretto Moderato con moto Allegro non troppo Adagio Moderato - INTERMISSIO - MAURICE RAVEL (1875-1937) String Quartet in F Major Allegro moderato: Tres doux Assez vif: Tres rhythme Tres lent .,... Vif et agite WOLFGANG AMADEUS MOZART (1756-1791) Quartet in E-flat Major, K. 428 . t • Until the great quartets of Haydn and Mozart, eighteenth century · t r chamber music had been written primarily for the private use of ama - r teurs. As the century progressed, the dominance of complex, Baroque compositional methods had diminished and the style of writing had been simplified, making it easier for an amateur to master. Yet, at the same time in Vienna, the public performance of larger-scale, symphonic music came into vogue. And as this was written for professionals, the composer could explore greater complexity, even bringing back some of the intricate devices of baroque music such as fugues. Furthermore, in the last decades of the century, a full-time, professional quartet was maintained in Vienna by Count Razumovsky for performances at the great houses. -

Digital Booklet Porgy & Bess

71 TRACKS THE AMADEUS QUARtet ReCORDINGS VOL. I BEETHOVEN Berlin, 1950-1967 recording producer: Wolfgang Gottschalk (Op. 127) Hartung (Op. 59, 2) Hermann Reuschel (Op. 18, 2-5 / Op. 59, 1 / Op. 130-133 / Op. 135 / Op. 29) Salomon (Op. 18, 1+6 / Op. 59, 3 / Op. 95) recording engineer: Siegbert Bienert (Op. 18, 5 / Op. 130-133 / Op. 29) Peter Burkowitz (Op. 18, 6) THE Heinz Opitz (Op. 18, 2 / Op. 59, 1+2 / Op. 127 / Op. 135) Preuss (Op. 18, 1 / Op. 59, 3 / Op. 95) Alfred Steinke (Op. 18, 3+4) AMADEUS QUARtet ReCORDinGS Berlin, 1950-1967 Eine Aufnahme von RIAS Berlin (lizenziert durch Deutschlandradio) recording: P 1950 - 1967 Deutschlandradio research: Rüdiger Albrecht remastering: P 2013 Ludger Böckenhoff rights: audite claims all rights arising from copyright law and competition law in relation to research, compilation and re-mastering of the original audio tapes, VOL. I BEETHOVEN as well as the publication of this CD. Violations will be prosecuted. The historical publications at audite are based, without exception, on the original tapes from broadcasting archives. In general these are the original analogue tapes, MstASTER RELEASE which attain an astonishingly high quality, even measured by today’s standards, with their tape speed of up to 76 cm/sec. The remastering – professionally com- petent and sensitively applied – also uncovers previously hidden details of the interpretations. Thus, a sound of superior quality results. CD publications based 1 on private recordings from broadcasts cannot be compared with these. AMADEUS-QUARtett further reading: Daniel Snowman: The Amadeus Quartet. The Men and the Music, violin I Norbert Brainin Robson Books (London, 1981) violin II Siegmund Nissel Gerd Indorf: Beethovens Streichquartette, Rombach Verlag (Freiburg i. -

The String Quartet

The Cambridge Companion to THE STRING QUARTET ............ edited by Robin Stowell published by the press syndicate of the university of cambridge The Pitt Building, Trumpington Street, Cambridge, United Kingdom cambridge university press The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge, CB2 2RU, UK 40 West 20th Street, New York, NY 10011–4211, USA 477 Williamstown Road, Port Melbourne, VIC 3207, Australia Ruiz de Alarcon´ 13, 28014 Madrid, Spain Dock House, The Waterfront, Cape Town 8001, South Africa http://www.cambridge.org C Cambridge University Press 2003 This book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press. First published 2003 Printed in the United Kingdom at the University Press, Cambridge Typeface Minion 10.75/14 pt. SystemLATEX2ε [tb] A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloguing in Publication data The Cambridge Companion to the string quartet / edited by Robin Stowell. p. cm. – (Cambridge companions to music) Includes bibliographical references and indexes. ISBN 0 521 80194 X (hardback) – ISBN 0 521 00042 4 (paperback) 1. String quartet. I. Stowell, Robin. II. Series. ML1160.C36 2003 785.7194 – dc21 2003043508 ISBN 0 521 80194 X hardback ISBN 0 521 00042 4 paperback Contents List of illustrations [page viii] Notes on the contributors [ix] Preface [xii] Acknowledgements [xiv] Note on pitch [xv] r Part I Social -

Meccore String Quartet

Meccore String Quartet FRIDAY, FEBRUARY 26, 2021, 7:30PM SATURDAY, FEBRUARY 27, 2021, 7:30PM SUNDAY, FEBRUARY 28, 2021, 3PM FROM OUR CHAMBER TO YOURS Our 68th Year... Our First Virtual Season 1 1 Since 2003, Altavista has oered our clients experience, versatility, discipline, and highly personalized service. Discover what the right investment rm can do for you. 4 Vanderbilt Park Drive Suite 310 Asheville, NC 28803 828.684.2600 [email protected] altavistawealth.com 2 About the Asheville Chamber Music Series Welcome to the 68th season of the Asheville Chamber Music Series. We are excited to share this year’s lineup of world-class chamber ensembles as we have done for the past 67 years. As always, we wish to thank you, our loyal audience of subscribers, patrons, donors and chamber music lovers. The ACMS thrives because of you and we are grateful. Founded in 1952 by Joe Vandewart, a refugee from Nazi Germany and ten other music lovers, the Asheville Cham- ber Music Series began modestly. After setting up a table in the lobby of the Battery Park Hotel, the group quickly found 800 people willing to pay the $4 price for a season subscription for “an unspecified number of concerts.” The Alberni Trio gave the first concert on October 16, 1952. Since then, chamber ensembles from around the world have performed for the Series. These include the Buda- pest, Emerson, Fine Arts, Juilliard, and Kodaly Quartets, along with trios, piano quartets, quintets and larger cham- ber ensembles as well as duos, such as the one featuring cellist Janos Starker and flautist Jean-Pierre Rampal. -

Program Trio in C Major, No

Long Theater * Stockton, California * March 31, 1979 * 8:00 p.m. FRIENDS OF CHAMBER MUSIC in cooperation with UNIVERSITY OF THE PACIFIC, and SAN JOAQUIN DELTA COLLEGE present Bruno Canino, piano Cesare Ferraresi, violin Rocco Filippini, cello PROGRAM TRIO IN C MAJOR, NO. 43 (HOBOKEN XV NO. 27) • (Franz) Joseph Haydn (1732 - 1809) Allegro Andante Finale (Presto) TRIO IN A MINOR (1915) . ... Maurice Ravel Modere (1875 - 1937) Pantoum (Assez vif) Passacaille (Tres large) Final (Anime) INTERMISSION TRIO IN B FLAT MAJOR, OPe 97 •• ..... Ludwig ("The Archduke") van Beethoven Allegro moderado (1770 - 1827) Scherzo (Allegro) Andante cantabile, rna pero con moto (Variations) Allegro moderato - Presto Trio di Milano is represented by Mariedi Anders Artists Manage ment, Inc., 535 El Camino Del Mar, San Francisco, California. The TRIO DI MILANO, composed of three noted and talented musicians, was formed in the spring of 1968. Engaged by the most important Italian musical societies to play at Milan, Torino, Venice, Rome, Florence, Pisa, Genoa, and Padua, the Trio has also performed in Germany, Switzerland, Spain, Portugal and the United States and has been acclaimed with enthu siasm and exceptional success everywhere. CESARE FERRARESI was born at Ferrara in 1918, took his degree for violin at the Verdi Conservatorio of Milan, where he is now Principle Professor. Winner of the Paganini Prize and of the International Compe tition at Geneva, he has now for many years enjoyed an intensely full and busy career as a concert artist. Leader of the Radio Symphony Orchestra (RAI) at Milan and soloist of the "Virtuosi di Roma", he has played at the most important music festivals at Edinburgh, Venice, Vienna, and Salz burg and in the major musical centers of Europe, Japan, and the United States. -

Curriculum Vitae Ida Bieler

Curriculum Vitae Ida Bieler Nationality: USA Languages spoken and written: English, German MAJOR POSITIONS Teaching Since 1993 – Robert Schumann Hochschule, Düsseldorf, Germany Full Professor for Violin and Chamber Music 1988 – 1993 Hochschule für Musik und Darstellende Kunst, Frankfurt am Main, Germany Full Professor for Violin and Director of Violin Pedagogic Department Since 2009 – Universität für Musik und Darstellende Kunst, Graz, Austria Adjunct Professor Since 2013 – University of North Carolina School of the Arts, Winston-Salem, North Carolina, USA Adjunct Professor 2005 – 2007 Guildhall School of Music and Drama, London, Great Britain Visiting Professor for Violin and Chamber Music 1983 – 1986 Hochschule für Musik Köln Abteilung Wuppertal, Germany Adjunct Faculty 1974 – 1978 Westminster Choir College, Princeton, New Jersey, USA Pre-College Violin Instructor Adjunct Faculty Orchestral 1982 – 1987 “Gürzenich-Orchester Köln”, Symphony and Opera Orchestra of Cologne, Germany Concertmaster MAJOR ENSEMBLES String Quartet 1993 – 2005 Melos Quartet, Stuttgart, Germany 2005 – 2010 Heine Quartet, Düsseldorf, Germany 1983 – 1993 van Hoven String Quartet, Cologne, Germany Piano Trio 2001 – 2015 Xyrion Piano Trio, Cologne, Germany 1985 – 1990 Mendelssohn Trio Berlin, Berlin, Germany Mixed Ensembles: Strings, Winds and Piano 2002 – 2018 Robert Schumann Ensemble, Düsseldorf, Germany 1995 – 2003 Ensemble Villa Musica, Rheinland-Pfalz, Germany 1993 – 2009 Ensemble Animabile, Düsseldorf, Germany INTERNATIONAL PERFORMING CAREER • Over 40 years -

Concertfriday, 9

ConcertFriday, 9. december 2011, 19:45 Caffe ART Hotel PIRAMIDA Feguš String Quartet Franz Schubert String Quartet in E- flat major D 87, op.post. 125,1 Allegro moderato Scherzo.Prestissimo Adagio Allegro Alban Berg String Quartet Op. 3 I. Langsam II. Mäßige Viertel Sašo Grozdanov Frédéric Chopin Ballade No. 1 Op. 23 in G minor Sergei Rachmaninov Etudes-tableaux Op. 33 No. 2 in C major Sergei Prokofiev Sonata No. 3 Op. 28 in A minor Feguš String Quartet has been performing since 1992, it’s members are brothers: Filip and Simon Peter – violin, Andrej – viola and Jernej – cello. They started their educational path at Maribor Music Conservatory, after which their studies continued at State Conservatory of Carinthia in Klagenfurt (Austria). Since year 2008 they are enrolled in master studium of chamber music at »Universität für Musik undarstellende Kunst Graz« by Stephan Goerner (Carmina Quartet). Sašo Grozdanov comes from Maribor. He is a PhD student of theoretical physics at Oxford University and is also one of the active participants at this symposium. He is an excellent pianist and he also attended some lectures on conducting at Academy of Music in Ljubljana. Feguš String Quartet “Brothers Feguš have obtained their place under of world – known quartets: Alban Berg Quartet, the sun with high level of their art by which they Amadeus Quartet, Borodin Quartet, Emerson insist. Their performance is distinguised by high Quartet, Juilliard Quartet, LaSalle Quartet, Guarneri level of focus, rounded sound, related experiencing Quartet as well as others. of musical arts, important talent and knowledge worth of consideration. -

Takács Quartet 1928, in Brno by the Moravian String Quartet

CAL PERFORMANCES PRESENTS PROGRAM NOTES Sunday, February 19, 2012, 3pm Leoš Janáček (1854–1928) primary beneficiary; Zdenka had to go to court Hertz Hall String Quartet No. 2, “Intimate Letters” to get that provision overturned.) The domestic tensions between the Janáčeks flared into a nasty Composed in 1928. Premiered on September 11, quarrel on New Years Day 1928, and Leoš deter- Takács Quartet 1928, in Brno by the Moravian String Quartet. mined to retreat to his cottage in his native vil- lage of Hukvaldy, but he was stuck in Brno for a Edward Dusinberre first violin In the summer of 1917, when he was 63, Leoš week finishing the opera The House of the Dead. Károly Schranz second violin Janáček fell in love with Kamila Stösslová, the He visited Kamila for two days before arriving Geraldine Walther viola 25-year-old wife of a Jewish antiques dealer in Hukvaldy on January 10th, and saw her again from Písek. They first met in a town in central at the performance of Katya Kabanova in Prague András Fejér cello Moravia during World War I, but, as he lived in on the 21st. A week later, from Hukvaldy, he Brno with Zdenka, his wife of 37 years, and she wrote to Kamila that he was beginning “a musi- lived with her husband in Písek, they saw each cal confession,” a new string quartet that he pro- PROGRAM other only infrequently thereafter and remained posed titling “Love Letters,” and which would in touch mostly by letter. The true passion seems call for a viola d’amore—the “viol of love”— to have been entirely on his side (“It is fortu- rather than the usual viola. -

Professor Norbert Brainin, Primarius of the Amadeus Quartet ‘Asfree, As It Is Rigorous’— Beethoven’S Art of Four-Voice Composition

Click here for Full Issue of Fidelio Volume 7, Number 3, Fall 1998 INTERVIEW Professor Norbert Brainin, Primarius of the Amadeus Quartet ‘Asfree, as it is rigorous’— Beethoven’s Art of Four-Voice Composition Norbert Brainin, former head of the legendary Amadeus Quartet, turned S N R Beethoven really took the I seventy-five in March 1998. Shortly E after his birthday, he granted a concept, ‘As free, as it is wide-ranging interview, with And then, as the final factor, you add the Beethoven as the focus. The inter- rigorous,’ earnestly. This is his pressure. This is something that the artist view was conducted by Ortrun and first commandment. Bach also must discover, and it is different every Hartmut Cramer on March 19 at wrote in four voices; but, with day. You must learn it, and practice it Elmau castle near Munich, Ger- every day, practice it over again, until it many, where Brainin was holding him, the voices are not works. I can only explain it thus: that one of his master classes for young individual. With Beethoven, when it really works, a tone comes forth string quartets, and first appeared in which is a full expression. I can demon- Ibykus, the German-language sister every voice is different, although strate this with singing, too. Whatever my publication of Fidelio. distinctly stamped by the voice might be, it nonetheless really comes Motivführung. This is his from me. And this voice has true expres- Fidelio: Professor Brainin, in one sion. You need such a tone, in order to of your earlier interviews [with great achievement.